The full story of the Royal Canadian Navy’s contribution to Allied victory in WW II has not been told. In Ottawa, the much-reduced Directorate of History at the Department of National Defence is preparing a multi-volume official history, but this will take some years to complete.Until these books are published we must rely on Joseph Schull’s Far Distant Ships and on a number of detailed accounts of specific parts of the story. Marc Milner’s two books North Atlantic Run and The U-boat Hunters are first-rate studies of the Canadian role in the Battle of the Atlantic and David Zimmerman has introduced us to the politics of the naval war effort in The Great Naval Battle of Ottawa. However, we lack an overview that would allow us to place such specialized studies in perspective. Looking at the pieces of the story leads to a typically Canadian tendency to see failure where others might claim success.

Milner offers an analysis of the events that led to the withdrawal of Canadian Escort Groups from the mid-Atlantic in January 1943. He describes the decision to give the sorely tried navy an opportunity to re-equip its ships and obtain long overdue training as evidence that the RCN had failed. This view, which is echoed by most of today’s naval historians, was the basis for the latest attempt of the McKenna brothers to uncover more examples of the villainy and incompetence which they believe mark Canada’s war effort.

Failure is a difficult judgment to apply unless you have a realistic idea of what constitutes success. A brief look at the challenges faced by the RCN and its achievements in the first three years of the war may help us to decide how we wish to evaluate the navy’s contribution.

The RCN was created amidst great political controversy in 1910 and emerged from WW I with a handful of small coastal defence ships. In the 1920s the navy with just two destroyers and two minesweepers–divided between the two coasts–almost disappeared. Fortunately two new destroyers, Saguenay and Skeena, were ordered in 1929 and their delivery helped to ward off depression-era threats to disband the entire navy. With the return of Mackenzie King to power in 1935 the Liberals, still sympathetic to plans for a Canadian navy, found the money to purchase more destroyers before the outbreak of war.

Given the Canadian government’s reluctance to permit general rearmament and King’s whole-hearted support for appeasement the navy had done very well, but what role could six destroyers and a few minesweepers play? The only likely tasks were to assist the Roval Navy as part of a destroyer screen for battleships or local defence against German commerce raiders. Perhaps someone should have argued the case for anti-submarine warfare training but no one did because the German navy possessed few U-boats and the RN was confident that air patrols, sonar and convoys would quickly crush a submarine offensive before it became a serious threat.

This conventional wisdom on the U-boat threat is often used as evidence to attack the leadership of the RN, but in the late 1930s it was based on the best information available. The real threats to the freedom of the seas were the Japanese and Italian fleets plus the new German pocket battleships. No one could have foreseen that the fall of France would provide Admiral Karl Donitz with bases on the French coast avoiding the bottleneck of the North Sea passages and providing easy access to the Atlantic. Hitler had no idea that the U-boat would become his principle weapon in a war of attrition against Britain. He thought the British would accept the inevitable or sue for peace when the Luftwaffe had demolished London. After a year of war German industry only succeeded in replacing the 28 U-boats lost at sea and it was not until mid-1941 that enough subs were available to challenge convoys in the mid-Atlantic.

The RCN, which relied on the RN for technical advice as well as operational guidance, did not pay much attention to anti-submarine warfare. Trying to cope with a tenfold increase in ships and an eightfold increase in ratings while teaching the rudiments of navigation and gunnery kept everyone busy. Much was accomplished when the entire fleet of Canadian destroyers sailed for British waters in the summer of 1940 the RCN was well prepared to join in the vital task of defending the British Isles from German invasion.

The sinking of the unarmed passenger liner Athenia in September 1939 reminded Canadians of the U-boat menace from WW I. The first contracts for a new escort, to be called a corvette, were issued. Corvettes, “cheap and nasties” in Churchill’s phrase, were to be used in coastal waters. No one imagined they would be needed in the mid-Atlantic.

The first Canadian-built corvettes, intended for the RN and manned with scratch RCN crews for the passage to Britain, were caught up in the U-boat crisis of the winter of 1940-41. They joined the RCN destroyers, now assigned to the Clyde Escort Force, in the crucial struggle to defeat the U-boat wolf-packs that were concentrated in the western approaches.

From a purely Canadian point of view British insistence on the emergency employment of the corvettes before they could be properly manned or equipped was a serious problem. It was on a par with the request that the RCN accept six of the 50 WW I destroyers obtained from the United States in the destroyers-for-bases deal. Finding crews with enough trained officers and ratings for six destroyers that you didn’t need or want was no easy task. However, it was impossible to argue with the strategic value of an agreement that involved the still-neutral U.S. in the defence of the western Atlantic.

Despite these demands, which placed the core of the RCN in the U.K. under British command, the navy found the resources to commission 23 corvettes for use in North American waters. Unfortunately, plans for Halifax-based convoy escort were thrown overboard when the U-boats, seeking easier targets, moved west of Iceland. On May 20, 1941, the British admiralty asked the RCN to establish a new base in St. John’s, Nfld., and to use its own resources to escort convoys from St. John’s to the mid-ocean meeting point south of Iceland.

The new Canadian corvettes were far from ready for mid-ocean escort duty, but there was little choice except to improvise and learn on the job. The first group, Agassiz, Alberni, Chambly, Cobalt, Collingwood, Orillia and Wetaskiwin sailed for “Newfyjohn” on May 23, 1941. Beyond a small number of professionals and a sprinkling of veteran petty officers, the ships were manned by volunteers of the Wavy Navy, the Royal Cdn. Naval Volunteer Reserve.

The ships were as ill-prepared as their crews, lacking even a breakwater to prevent the sea from cascading into the open well-deck. The RCN was also short of gyro compasses and modern sonar so the new corvettes got magnetic compasses and obsolete asdic sets. There was no radar to install and no clear sense that it was needed. The senior officer, Commander J.D. “Chummy” Prentice, was an innovative leader who worked steadily to improve efficiency but with new ships arriving each month there was a limit to what could be done.

There were bright moments amidst the gloom. In September 1941 Prentice took his HMCS Chambly with HMCS Moose Jaw to sea on a training exercise. When reports of a wolf-pack attack on an eastbound convoy arrived, his small task force raced to assist the outnumbered escort group. Chambly’s asdic operator got a firm contact and depth charges brought U-501 to the surface where it was rammed by Moose Jaw.

This was the RCN’s first kill of a German submarine and there was good reason for satisfaction though none for complacency. The convoy had lost 16 ships because an escort of one destroyer and three corvettes could not possibly hold off a determined attack by a dozen U-boats. The solution was simple; more and better escorts, improved training and air cover in the “Black Hole” south of Greenland.

In time all of this would happen, but not in 1942. The RCN was constantly overwhelmed by new demands and there was neither the time nor resources to provide the training, refits or new equipment required. The RCN was required to join in the task of escorting convoys all the way across the Atlantic, but it was also needed to help the Americans overcome the U-boat campaign off the east coast of the U.S.

The decision to withdraw the RCN from mid-ocean escort in January 1943 was long overdue. If circumstances had permitted this respite in the first half of the year the Canadians would have played an active part in the climactic battle of May 1943 and historians would write about the RCN’s extraordinary achievement. Someday, upon reflection, they will.

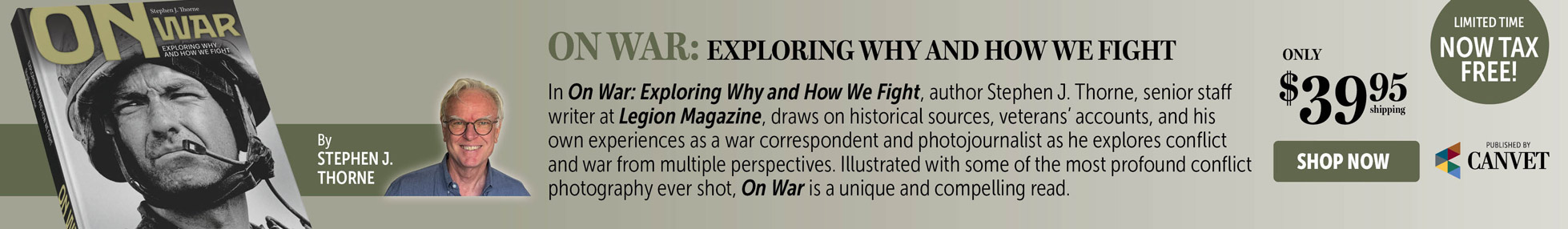

Advertisement