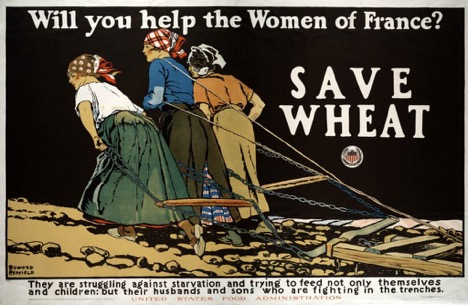

This poster was part of an international relief effort, begun by the United States, to fight wartime famine. More than 10 million Belgian and French citizens relied on food relief during four years of German occupation.

When fighting drew near to the small village of Montigny-en-Ostrevent, France, near the end of the First World War, civilians wisely evacuated.

When they returned home, many found their houses and cottages occupied by Canadian liberators—squatters who were nonetheless warmly welcomed.

“We struck a fine cottage for a billet,” wrote signaller Elmer McKay of the Toronto Regiment in his diary on Oct. 23, 1918. “Cleaned out the house. Got bed to sleep in. Table to eat at, with full dinner set. Vase of flowers. Stove with plenty of coal for fire. Made a real comfy Home Sweet Home. This is a jake old war. Almost every night since start from Canal de la Sensée we have found a bed to sleep in. Aaaa…”

The next day, they discovered villagers’ gardens “still full of vegetables.” Of which they no doubt took liberal advantage.

Within two days, villagers began returning.

“They are perfectly satisfied to have soldiers sleeping in their houses,” reads the war diary of the 3rd Battalion on Oct. 25, 1918. “Our men and the civilians most friendly. ‘Soldats Canadienne très bon’ is all they say. Our men share their rations with them. The French are very grateful as they have not had meat for three years. They are in very bad shape physically through starvation by the Huns.”

Three days later, relief supplies began to arrive. “There are nine men and 20 women and one child, all without food. The men divide their rations with them and assist them every way possible,” said the diary.

Yet when soldiers investigated the cellar at nearby Lambrech Chateau, which had at times hosted German General Erich Ludendorff and President Paul Von Hindenburg, they found “thousands of bushels of potatoes,” wrote McKay. “Fritz flooded the cellar, but we got to work and rescued the murphies.”

As the war ground on and on, food shortages spread farther and farther across Europe. Germany regularly requisitioned food from the local population in occupied territory, since German citizens themselves were on a near-starvation diet.

The shortages even reached the Middle East. “Jerusalem has not seen worse days,” wrote Arab diarist Ihsan Turjman in 1916. “Bread and flour supplies have almost totally dried up…for several days the municipality distributed some kind of black bread to the poor, the likes of which I have never seen. People used to fight over the limited supplies, sometimes waiting in line until midnight. Now, even that bread is no longer available.”

The First World War was also a war of bread and potatoes, said historian Avner Offner. The situation was not immediately rectified after the war. In France, fields were littered with unexploded artillery shells and had to be cleared before crops could be sown. Those shells continue to surface even today.

Advertisement