A bronze caribou statue (top left)—emblem of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment—tops a granite cairn at the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial. The Canadian National Vimy Memorial (top right) was the destination of the Legion’s first pilgrimage in 1936. [Doris Williams]

In the early hours of Aug. 19, 1942, a largely Canadian military contingent conducted an ill-fated raid on German-occupied France. More than 6,000 infantry, including Private George Davies of the South Saskatchewan Regiment, landed on the beach at Dieppe that morning and faced deadly enemy fire. More than 3,600 of those who made it ashore were killed, wounded or captured, but Davies survived.

Seventy-seven years later, his daughter Kathleen Matteotti is making her own journey across the Atlantic as a member of the 2019 Royal Canadian Legion Pilgrimage of Remembrance. The Legion’s first pilgrimage was organized for the unveiling of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France in July 1936, and the Legion has conducted pilgrimages of remembrance since 1988.

On July 7, I join Matteotti and 28 others embarking by hired coach on a 13-day journey through three European countries and to dozens of battlefields, memorials and cemeteries from both world wars.

This year’s group consists of Legion First Vice Bruce Julian and his wife Darlene, tour co-ordinator Danny Martin and his wife Pam, tour assistant Randy Haley, 10 pilgrims chosen by their respective provincial commands and 13 paying pilgrims. Volunteer guide John Goheen, who has been lending his expertise to the pilgrimages since 1997, completes the roster.

The common thread of remembrance—never forgetting the sacrifices of those who served—draws these pilgrims together. For the provincial command pilgrims, it is an opportunity to learn and then pass their knowledge along to branches, schools and communities across Canada. It is also a personal journey for many—to find the grave of a loved one, a member of their military unit, or someone from their community or province. For Matteotti, it is a chance to stand right on the spot where her father served.

Dieppe is a pretty seaside city, its waterfront edged by limestone cliffs, seagulls hovering above beaches of smooth, round multicoloured rocks. A promenade parallels the water’s edge, where children frolic and the more adventurous swim. But if you look closely at those limestone cliffs, you can see the indents of German bunkers. And on the beach are remnants of concrete defensive barriers.

The early morning assault on Dieppe was a disaster. Tanks bogged down in the loose stones and concrete barriers blocked their advance. From fortified positions above the beaches, the Germans rained artillery fire down on the Canadians before they even made it out of the water.

Davies landed on Green Beach that day and got as far as the bridge in Pourville, says Matteotti. He recovered wounded soldiers from the beach to take them back out to the landing craft, she recalls him saying. But the landing craft had left the beach without him and he had to swim out to one of the retreating vessels.

Davies went on to serve in Italy, where he was wounded, and in Holland. While on this trip, Matteotti discovers, with help from Alberta pilgrim Kyle Scott, that her father had been mentioned in dispatches for his bravery.

“He came back with a little bit of shrapnel here and there, but other than what it did to him mentally, he was a kind, gentle soul,” Matteotti tells her fellow pilgrims.

The Dieppe Raid included naval, air and ground forces. In honour of the 550 naval casualties, the group conducts an informal ceremony on the Dieppe Pier. Saskatchewan pilgrim John Voutour drops a wreath into the water as Danny Martin pays tribute to their sacrifice.

The failure at Dieppe offered valuable lessons for another assault on another set of beaches in France two years later—on D-Day.

July 8 dawns clear and sunny, with just enough breeze to temper the heat. At 8 a.m., pilgrims gather on a dune overlooking the beach at Courseulles-sur-Mer as Goheen describes the scene at that very hour on June 6, 1944.

This is one of three beaches—Bernières-sur-Mer and Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer are also on the morning’s itinerary—that comprised the main landing areas in the Canadian contribution to Operation Overlord, the invasion of German-occupied Normandy by Allied forces. The morning attack succeeded, but not without a terrible price: Canadian casualties included 340 killed, 574 wounded and 47 captured.

We descend the dunes and walk the beach. There is more beachfront now than when landing craft approached the shore and soldiers plunged into the frigid waters. Scott hikes to the water’s edge and dips his feet into the English Channel. As we return to the coach, I overhear an exchange behind me.

“Those sand dunes are hard to walk up,” says one pilgrim.

“Imagine carrying a 50-pound pack,” says another, “and someone shooting at you.”

We drive through villages liberated by Canadians in June 1944, with stone walls and ruler-perfect hedges lining narrow roads. Stone buildings and brick houses give way to open fields of wheat and corn. These are quiet, peaceful towns now, but they mark what Goheen describes as dark days following the invasion.

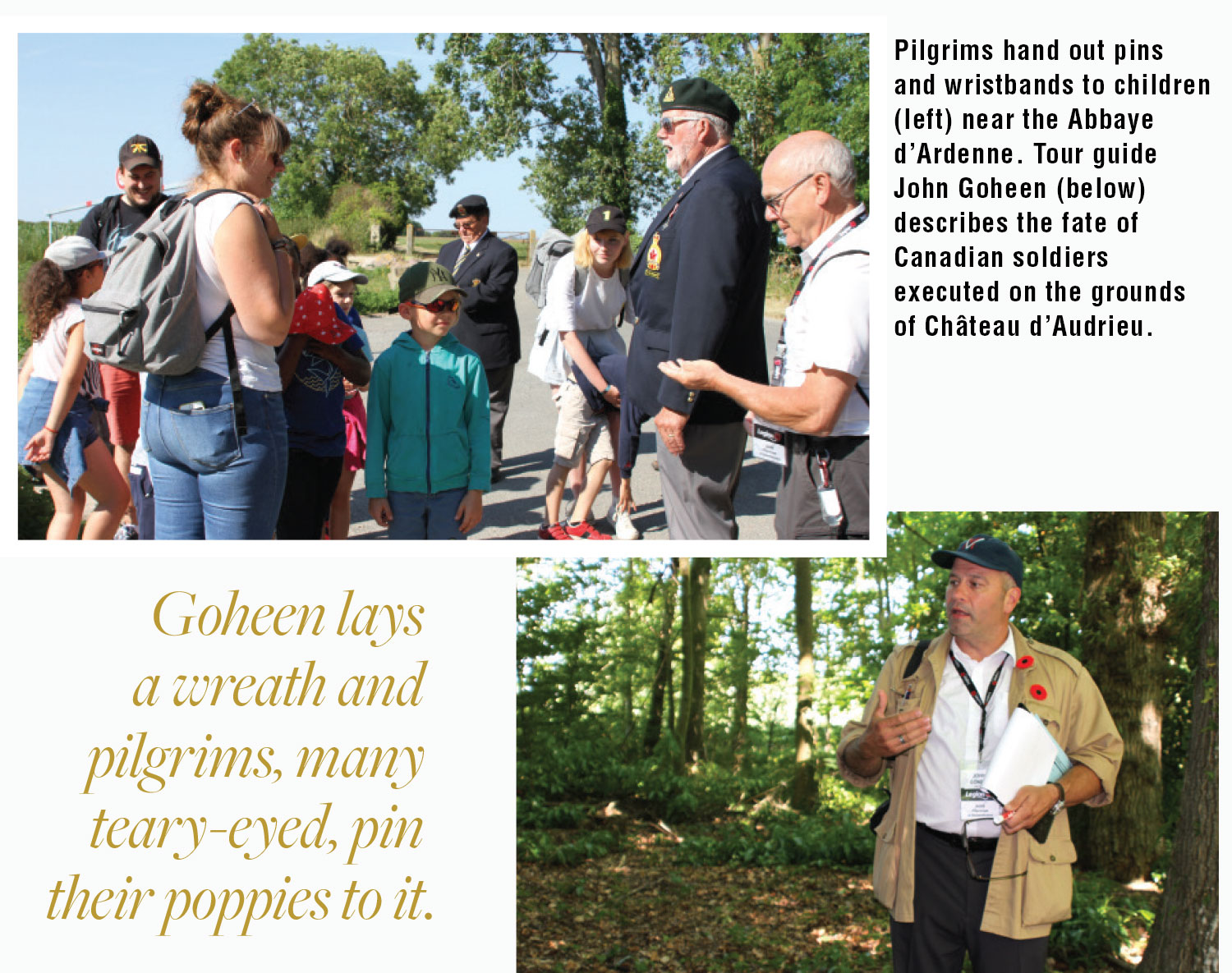

We stand in a large stone courtyard in the Abbaye d’Ardenne near Caen as Goheen describes the scene on June 7, 1944, when the monastery was occupied as a command post by the German 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth).

Fifty Canadian prisoners of war were held here. Having been interrogated and given nothing up, 11 of them were led to the garden of the abbey and executed one at a time, six of them with a sharp blow to the back of the head with an icepick. In all, 20 Canadian soldiers were executed in or near the garden by June 17.

The pilgrims conduct the first commemoration ceremony here. As dappled light pierces the overhanging trees, British Columbia/Yukon pilgrim and sergeant-at-arms Eric Callaghan marches the colour party to a cenotaph erected in the soldiers’ memory. “O Canada” and “Last Post” are followed by two minutes of silence, then “The Lament” and “The Rouse” are played. Julian recites the Act of Remembrance and he and Nova Scotia/Nunavut pilgrim Gary Siliker move to the monument. Siliker places a wreath and both pin their poppies to it and salute. The ceremony finishes with “God Save the Queen.”

Ceremony complete, several pilgrims hand out commemorative wristbands and pins to a group of smiling children, a soothing balm for the horrors we have just heard.

The emotional day does not end there. At Audrieu, Goheen leads us down a tree-lined path to a nondescript clump of woods surrounding Château d’Audrieu. On June 8, 1944, German troops executed 24 Canadian and two British soldiers on these grounds. One was holding a picture of his mother and father when he was killed. Goheen places a wreath and pilgrims, many teary-eyed, pin their poppies to it.

There are 2,048 burials at the Bény-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery east of the village of Reviers. Most are casualties from the 3rd Canadian Division who died on D-Day or in the subsequent advance on Caen. Pilgrims linger among the maple trees and headstones, placing Canadian, provincial or regimental flags on the graves of soldiers with whom they have a connection.

On the eighth day, the tour travels north into the Netherlands to visit sites associated with the Battle of the Scheldt, including a German bunker in the Breskens Pocket where Canadians faced 29 days of fierce fighting before taking the territory on Nov. 3, 1944.

We stop along a narrow road between the high bank of a dike and low-lying fields of wheat. Climbing the grassy dike wall, we are treated to a panoramic view of Braakman Inlet, where Canadian forces landed and moved inland in a successful effort to take the south Scheldt from German control.

Pilgrims place flags on graves (top) in the Bény-sur-Mer Canadian War Cemetery. Names of 35,000 soldiers with no known grave are etched on the wall of the Tyne Cot Memorial to the Missing (above). [Doris Williams]

The focus shifts to the First World War as we enter the Belgian city of Ypres. This area witnessed some of that war’s most brutal fighting. Ypres itself was reduced to rubble, with only two buildings surviving. The city was rebuilt, including the impressive Cloth Hall. A marketplace built during the Middle Ages, the Gothic hall was meticulously restored after the war. Its imposing towers and striking gold clock dominate the town, and the complex now houses the In Flanders Fields Museum, which presents the story of the First World War in the West Flanders region.

Major battles were fought in the Ypres Salient—a bulge in the front line—from 1914 to the war’s end on Nov. 11, 1918. More than 100 war cemeteries and memorials in the Ypres area are reminders of the tremendous and tragic loss of life.

Tyne Cot Cemetery is the largest Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery in the world. Its immenseness cannot be captured with a lens and is very hard for the heart to take in as well. Buried here are nearly 12,000 servicemen who died in the fighting around Ypres, of which almost 8,300 are unidentified. Around the eastern boundary of the cemetery is the Tyne Cot Memorial. Etched on its walls are the names of an additional 35,000 servicemen who fought in the Ypres Salient and have no known grave.

We walk for a few minutes from the centre of Ypres to the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing. Hundreds of thousands of British Empire soldiers marched through the Menin Gate on the way to battle. Unveiled on July 24, 1927, the memorial’s panels display the names of more than 54,000 soldiers killed in the Ypres Salient whose burial sites are unknown. A commemorative ceremony has been conducted under its vaulted arches every evening since 1928, except during the Second World War when the city was occupied by Germany. Its limestone walls bear scars from Second World War shelling—a reminder that peace seems untenable.

On July 15, four pilgrims from our group participate in the ceremony, while the rest observe. Julian, Scott, Goheen and Ontario pilgrim Dianne Hodges place the first wreath of the ceremony, and Julian recites the Kohima Epitaph: “When you go home, Tell them of us and say, For your tomorrow, We gave our today.”

Rural areas in these parts of Belgium and France are primarily farmlands growing wheat, barley, corn, potatoes and cabbage. After more than a century, these fields still yield shell casings and shrapnel—and the bones of those who died in battle.

We approach a granite obelisk amid a sea of wheat on what was once a muddy battlefield. The 85th Battalion (Nova Scotia Highlanders) Memorial honours those who died in operations at Decline Copse and Vienna Cottage on Oct. 28-31, 1917, in the Second Battle of Passchendaele. We are surprised to find a rusted artillery shell, and Scott, who served as a combat engineer with 1 Combat Engineer Regiment, explains how to identify a live round. Fortunately, this one is spent.

Soldiers’ remains were often buried near or on battlefields, and dozens of such war cemeteries are clustered here in a relatively small area. More than once, our coach heads “off road” and we find ourselves jostling along nothing more than a tractor path, only to stop beside one of these little-visited cemeteries. It is heartwarming to see a group of pilgrims descend from the coach and move among the headstones, carefully placing Canadian flags. Heartbreaking is the sheer number of these stones bearing only the words “Known unto God.”

An unearthed shell placed on the base of the 85th Battalion (Nova Scotia Highlanders) Memorial. [Doris Williams]

The 10 pilgrims supported by provincial commands had been tasked with researching a First World War fatality from their province. Standing at each soldier’s graveside, they share what they’ve learned. From the first presentation to the last, it is obvious that each soldier has become their soldier. Several leave a framed photo or other mementoes at their soldier’s grave.

At the Courcelette British Cemetery in the Somme region of France, Manitoba pilgrim Peter Martin describes his soldier—Lieutenant Trevor Bell—through the eyes of his mother, Ruby Bell. Trevor was born on Feb. 14, 1895, and went to college in Toronto and Winnipeg before getting his first job as a customs broker with the Imperial Bank of Canada in Winnipeg. He joined the 79th Cameron Highlanders of Canada in 1915. Ruby walked with Trevor to the train station a few minutes from the family home for the trip to Halifax. He sailed to England on SS Lapland on Oct. 23, 1915, there joining the 44th Battalion. He then switched to the 27th, perhaps hoping to see action sooner—which he did on the battlefields of the Somme. On Sept. 15, 1916, Trevor was hit in the head by an enemy bullet, dying almost instantly. Martin ends with Ruby’s hope “that someone will remember the sacrifice of Trevor Bell.”

The Battle of the Somme was fought from July 1 to Nov. 18, 1916. More than 24,000 Canadian and Newfoundland soldiers were killed, wounded or missing in this bloody campaign. On the preserved battlefield near the village of Beaumont-Hamel, grass-covered trenches flank a walkway that leads to a bronze caribou statue, one of five in France that commemorate Newfoundland’s contribution and sacrifice in the war. On the morning of July 1, 1916, 780 members of this regiment attempted to take a hill defended by German fortifications. Only 68 answered roll call the next day. Newfoundland pilgrim Bill Duffitt places the wreath in a formal ceremony at the memorial.

At the Passchendaele New British Cemetery, I pause to reflect on the tour and the places it has taken us so far: to memorials that bear witness to the carnage of two world wars; battlefields where countless Canadian soldiers fought and died; cemeteries containing those, known and unknown, who fell nearby.

I join fellow Newfoundlander Duffitt and Siliker at the grave of R.N. Balsom of Clarenville, N.L., a sergeant with the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, and we sing the “Ode to Newfoundland,” putting extra emphasis on the lyric “Where once they stood, we stand.”

Standing at the grave of Lieutenant Trevor S. Bell in the Courcelette British Cemetery, pilgrim Peter Martin presents a biography of the young man who was killed in battle on Sept. 15, 1916. [Doris Williams]

A cool, light rain greets us on the tour’s final day, but the clouds lift by the time the coach reaches Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, the world’s largest French military cemetery, at Ablain-Saint-Nazaire. Its elliptical memorial attests to the resilience and compassion of the human spirit: listed alphabetically on its curving walls, with no distinction of rank or nationality, are the names of 580,000 soldiers who lost their lives in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region during the First World War. The hilltop memorial offers a sweeping view, including Vimy Ridge 10 kilometres away.

Even from a distance, the white limestone base and sculptured columns of the Vimy Memorial are impressive. But as you approach, its size and detail are breathtaking. On the surrounding grounds, preserved grass-covered trenches and red signs warning of live explosives are reminders that the memorial is atop a 102-year-old battlefield.

Vimy Ridge was occupied by Germany in October 1914. All four divisions of the Canadian Corps—fighting together for the first time—along with Britain’s 5th Division recaptured the ridge in a monumental four-day battle beginning on April 9, 1917. More than 10,600 Canadians were killed or wounded.

Inscribed on the memorial walls are the names of 11,285 Canadians killed in France during the war for whom there is no known grave. As we gather for the final commemoration ceremony, a group of teenaged students approaches and assembles alongside us at the base of the monument. As Padre Olav Kitchen gives the blessing, Scott lays a wreath and Julian reads the Act of Remembrance, all those assembled—pilgrims, students, other visitors—fall into a respectful silence, caught up in the act of remembering.

Advertisement