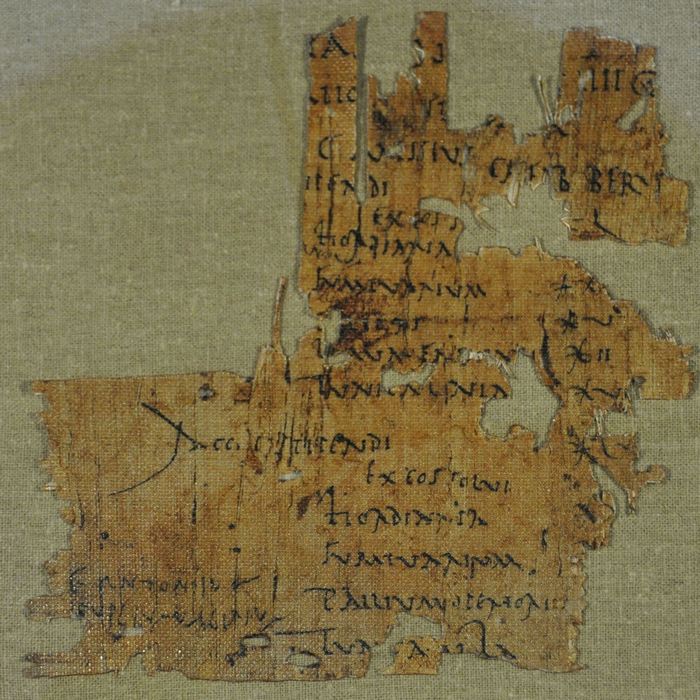

Fragment of a pay slip belonging to Gaius Messius, a Roman auxiliary soldier in the Legio X Fretensis, found at Masada and dating to the time of the siege. It shows that his entire pay went straight back to the army to pay for his meals, clothing, equipment and horse feed. [Dr. JE Ball/Twitter]

Written on a scrap of papyrus, the 1,900-year-old pay slip—one of only three ever found in the Roman Empire—shows that the imperial grunt was left penniless once the military recouped expenses for meals, equipment, clothes, even horse feed.

Gaius Messius, a Roman auxiliary soldier believed to have served during the legendary siege in the Judaean Desert between AD 72 and 75, had to repay his entire stipend to cover his essentials.

Discovered at a former fortified Roman encampment, the document provides a detailed summary of a fighting man’s salary over two of three pay periods, along with the various deductions.

“The fourth consulate of Imperator Vespasianus Augustus,” reads the document, according to a translation by the Database of Military Inscriptions and Papyri of Early Roman Palestine. “Accounts, salary. Gaius Messius, son of Gaius, of the tribe Fabia, from Beirut.

“I received my stipend of 50 denarii, out of which I have paid barley money 16 denarii; …food expenses 20 denarii; boots 5 denarii; leather strappings 2 denarii; linen tunic 7 denarii.”

The deductions, made in ancient Roman currency, are equivalent to the money he would have made had the military provided his necessities and fed his horse.

Oren Ableman, senior curator-researcher at the Dead Sea Scrolls Unit of the Israel Antiquities Authority, said that, while the document provides only a glimpse into a single soldier’s expenses in a specific year, “it is clear that in light of the nature and risks of the job, the soldiers did not stay in the army only for the salary.”

“The soldiers may have been allowed to loot on military campaigns,” he explained. “Other possible suggestions arise from reviewing the different historical texts preserved in the Israel Antiquities Authority Dead Sea Scrolls Laboratory.”

One of those documents, discovered in the Cave of Letters in Nahal Hever from the time of the Bar Kokhba Revolt (AD 132-135), exposes a side-hustle Roman soldiers used to earn extra cash: a signed loan deed in which a legionary charges a Jewish resident interest at a rate higher than permitted by the laws of the day.

“This document reinforces the understanding that the Roman soldiers’ salaries may have been augmented by additional sources of income, making service in the Roman army far more lucrative,” said Ableman.

As bad as compensation was for Gaius Messius, it was worse for his predecessors, who half-a-millennium earlier were compelled to serve and weren’t paid at all.

With the military reforms of Roman leader Gaius Marius in 102 BC, however, came a professional army and regular wages.

The foundations of modern service were set in AD 6, when Octavian Augustus created a special military treasure, or fund, to maintain the army and provide for war invalids and veterans. It was called Aerarium Militare.

Active soldiers received three stipends a year of 75 denarii each in January, May and September, or 225 denarii annually for each legionary. Riders received similar pay. Auxiliary soldiers such as Gaius Messius were awarded three stipends of 25 denarii each a year. Centurions, or commanders of company-sized units called centuria, typically earned five times more than regulars.

Then, as Judaism prohibits suicide, they drew lots to determine who would finish the job.

Built by the Rome-appointed client king of Judea, Herod the Great, between 37 and 31 BC, the fortress of Masada stands on the majestic heights of a plateau overlooking the Dead Sea southeast of Jerusalem.

Remote and inaccessible, Masada went largely unexplored for millennia.[Government of Israel]

During the First Jewish-Roman War, known as the Great Revolt, Masada was taken by the Sicarii (dagger-man), a splinter group of the Jewish Zealots and one of the earliest organized group of assassins. They slaughtered all 700 members of a Roman garrison at Masada.

The Sicarii were controversial then and remain so to this day, their courageous stand a matter of legend, but their methods—they wiped out an entire Jewish village, including women and children, and used starvation as a means of inciting the populace against the Roman occupation—the subject of criticism.

Gaius Messius is believed to have been serving with X Fretensis, a legion commanded by the Roman governor Lucius Flavius Silva. Supported by several auxiliary units and Jewish prisoners of war, it marched on Masada in or around AD 72 to break the Sicarii resistance. The force totalled some 15,000, 8,000-9,000 of whom were actual fighting men.

The Romans erected a siege wall 10 kilometres around the mountain plateau and supported it with a series of fortified encampments.

After several failed attempts to breach the Jewish defences, the Romans built a massive ramp scaling 61 metres up the western side of the fortress. A siege tower and battering ram were moved up, and in AD 73 the walls of Masada were finally breached.

The events that followed have divided historians and archeologists for centuries. According to the first-century Romano-Jewish historian Josephus Flavius, the soldiers found 960 men, women and children dead. He said the doomed defenders killed their own families.

“For the husbands tenderly embraced their wives and took their children into their arms, and gave the longest parting kisses to them, with tears in their eyes,” Josephus wrote.

“Yet at the same time did they complete what they had resolved on, as if they had been executed by the hands of strangers, and they had nothing else for their comfort but the necessity they were in of doing this execution, to avoid that prospect they had of the misery they were to suffer from their enemies.”

Then, as Judaism prohibits suicide, they drew lots to determine who would finish the job.

Wrote the historian: “They then chose ten men by lot out of them, to slay all the rest; everyone of whom laid himself down by his wife and children on the ground, and threw his arms about them and they offered their necks to the stroke of those who by lot executed that melancholy office; and when these ten had, without fear, slain them all, they made the same rule for casting lots for themselves, that he whose lot it was should first kill the other nine, and after all, kill himself.”

A Roman siege camp and section of the circumvallation wall dating from the time of the siege at Masada.[Oren Rozen/Wikimedia]

The shards on which Jewish archeologists claim the Sicarii wrote the names for the fateful draw are on display in the museum at the base of the mountain today.

Josephus wrote that the Sicarii leader, Eleazar ben Ya’ir, ordered their provisions destroyed to demonstrate to the Romans that they defiantly chose death over slavery. Ben Ya’ir’s name is on one of the recovered pottery shards.

According to Josephus, when the Roman siege ended, the legionaries discovered all the buildings, but the food storerooms had been set ablaze and all the occupants except two women and five children were dead.

It’s assumed that this account is based on the field commentaries of the Roman commanders. There are discrepancies between archeological findings and the ancient historian’s writings, the most glaring is the fact that the remains of only 28 individuals have been found.

Other details of the historian’s account were correct—including his descriptions of baths and the floors of some buildings that “were paved with stones of several colours,” and that many pits were cut into the rock to serve as cisterns.

Remote and arid, the site sat virtually untouched for two millennia until Professor Yigal Yadin led an archeological team on a 1963-1965 expedition to Masada. He said 25 of the remains were found along with fragments of linen and clothing in a cave near the top of its southern cliff, just below the casement wall.

A subsequent study found that 14 of the skeletons were of males between the ages of 22 and 60; one was of a man over 70; six were females between 15 and 22; and four were children from eight to 12 years old. There was also a single embryo.

The archeological team searched the site and made several exploratory sectional-cuts in places where similar finds seemed likely, but they yielded nothing.

“Most of the skulls belong to the same type as those we discovered in the Caves of Bar Kochba in Nahal Hever,” wrote Yadin. “It seems to me that these facts conclusively rule out the possibility that the skeletons are those either of the Roman garrison or of the [Byzantine] monks [who later occupied the site].

“They can be only those of the defenders of Masada.”

The archeological team searched the site and made several exploratory sectional-cuts in places where similar finds seemed likely, but they yielded nothing.

Another view of Masada, southeast of Jerusalem, with the Dead Sea in the background.[Andrew Shiva/Wikimedia]

The Roman attack ramp still stands on the western side and can be climbed on foot. The Romans’ metre-high circumvallation wall around Masada remains, as well as remnants of the eight Roman siege camps just outside.

Many of the ancient buildings have been restored, along with wall paintings of Herod’s two main palaces and the Roman-style bathhouses that he built. The synagogue, storehouses and Jewish rebel houses have also been restored.

The UN’s cultural body, UNESCO, registered Masada in its list of world heritage sites in 2001, citing its “majestic beauty” and its importance as a “symbol of the ancient kingdom of Israel, its violent destruction and the last stand of Jewish patriots in the face of the Roman army.”

Advertisement