It may have been the best investment Enos Collins, Benjamin Knaut and John and James Barss ever made.

The merchants of Liverpool, N.S., purchased Severn, a former American slave ship captured by the Royal Navy, in 1811 for a mere 420 British pounds (about C$53,000 today). Lucky for them, war broke out with the United States a few months later, and the boys were in business, big-time.

They renamed the Baltimore Clipper-style schooner Liverpool Packet, initially running mail between Liverpool and Halifax.

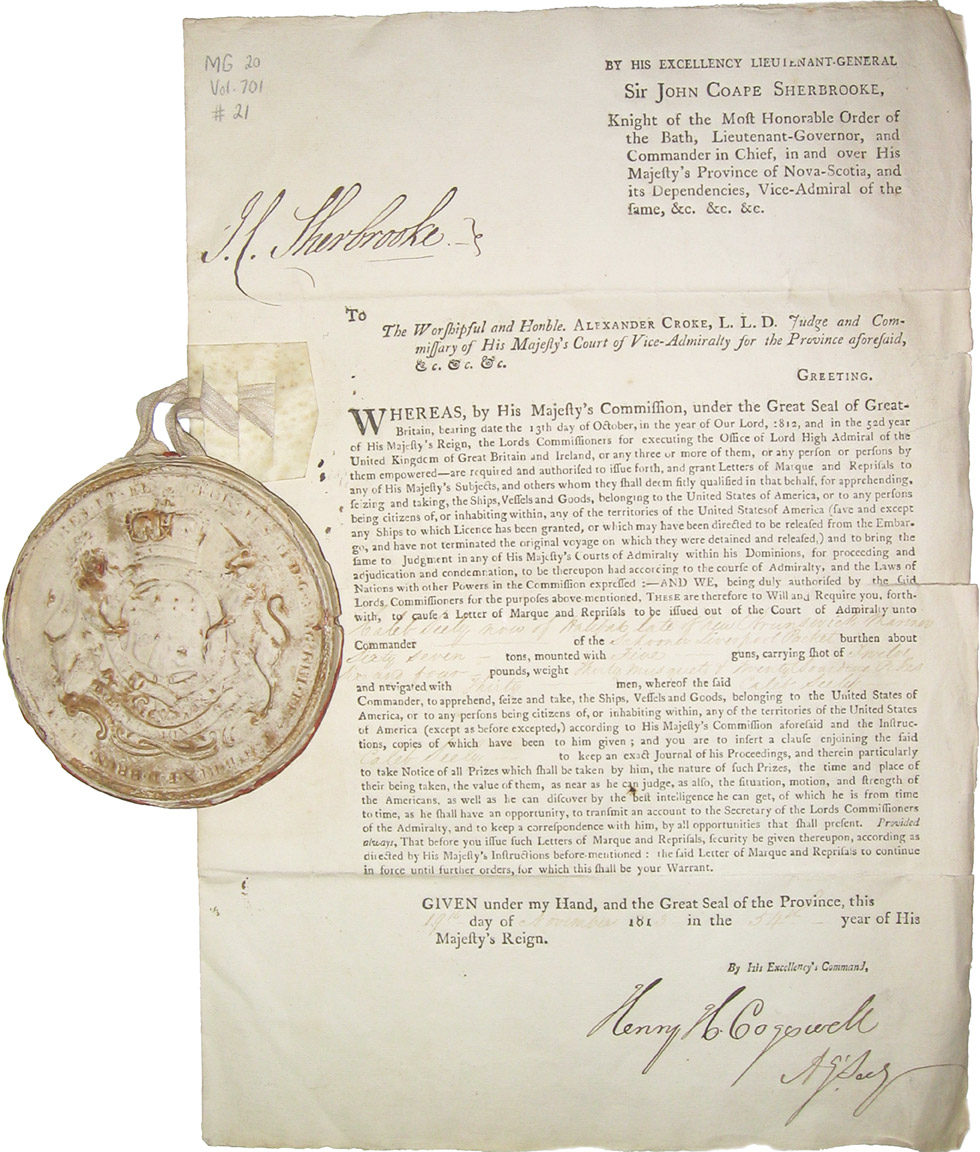

With the outbreak of the War of 1812, however, they acquired a letter of marque from the king of England and embarked on the most successful privateering spree mounted by any of the 40-odd Canadians licensed as maritime mercenaries during the conflict.

The speedy, upstart craft, with its five guns and 45 crew, captured some 50 American vessels and their cargoes, then worth between $264,000 and $1 million (equivalent to the 2019 purchasing power of C$6.6 million-$25 million).

Classic naval engagements such as the Battle of Lake Erie and the confrontation between HMS Shannon and USS Chesapeake, which ended with a captured Chesapeake paraded up Halifax Harbour, earned much of historians’ attention. But skirmishes between what were at their core small, hopped-up merchant and fishing vessels were a continuing feature of the last great conflict between America and Britain.

Colonial privateers played a key role in the War of Independence between 1775 and 1783, taking more than 3,000 British vessels and capturing coveted muskets and gunpowder for the Continental Army.

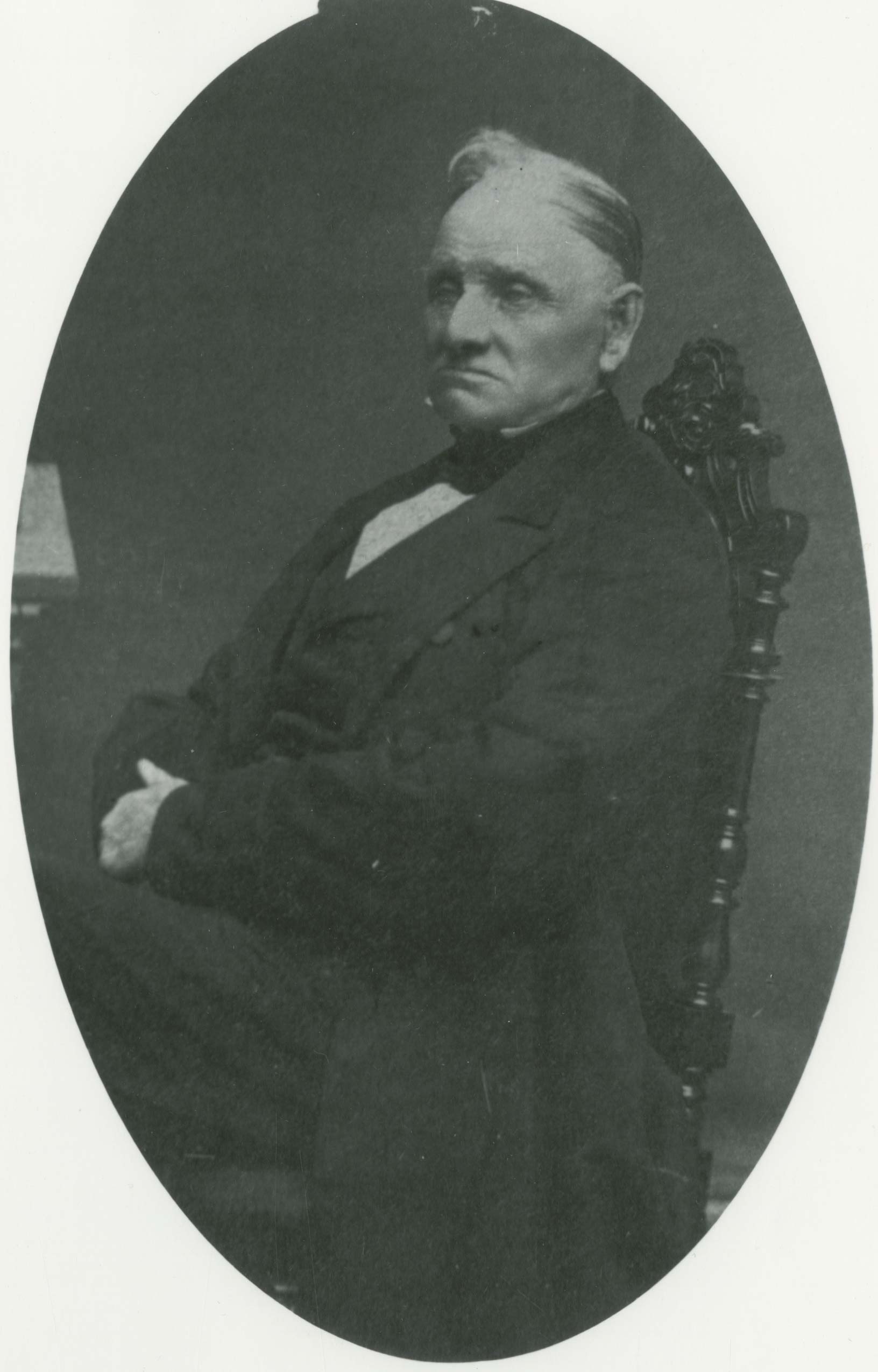

The success of the Liverpool Packet helped launch the fortune of its principal owner, Enos Collins, who would go on to found the Halifax Banking Co. [Wikimedia]

By 1814, British maritime insurance firms were routinely charging an unheard-of 13 per cent on shipments between England and Ireland. The Navy Chronicle reported that was triple what it was when Britain was at war “with all of Europe.”

The British monarch and his representatives issued some 4,000 letters of marque during the Napoleonic Wars, which included the period 1812 through 1815.

The documents—licences to plunder—represented win-wins for everyone involved, save for the hapless victims.

They essentially legitimized the practice of piracy against seagoing vessels, no matter how innocent they might be. By seizing and plundering merchant ships, fishing boats, whalers and others, privateers upset commerce, disrupted supply, distracted naval resources and, in some cases, made themselves fortunes.

“The privateers of Nova Scotia played an integral role in closing American ports during the War of 1812,” says The Canadian Encyclopedia. “They were a valuable source of intelligence for the Royal Navy on American strength and ship movements.

“While 15 commissioned ships from New Brunswick and Nova Scotia failed to capture any prizes and another 10 only took one each, the remaining privateers made fortunes for their owners.”

And none more than the Liverpool Packet.

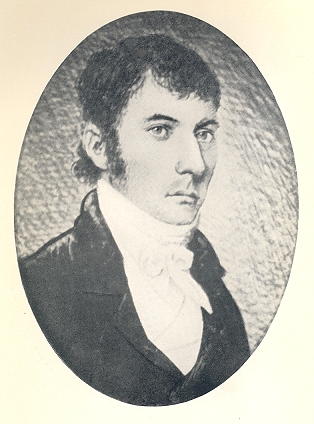

Commanded by Joseph Barss Junior, Packet captured at least 33 American ships in the war’s first year, 19 of them on her first two cruises. Barss would lie in wait off Cape Cod, Mass., attacking U.S. vessels headed to Boston and New York.

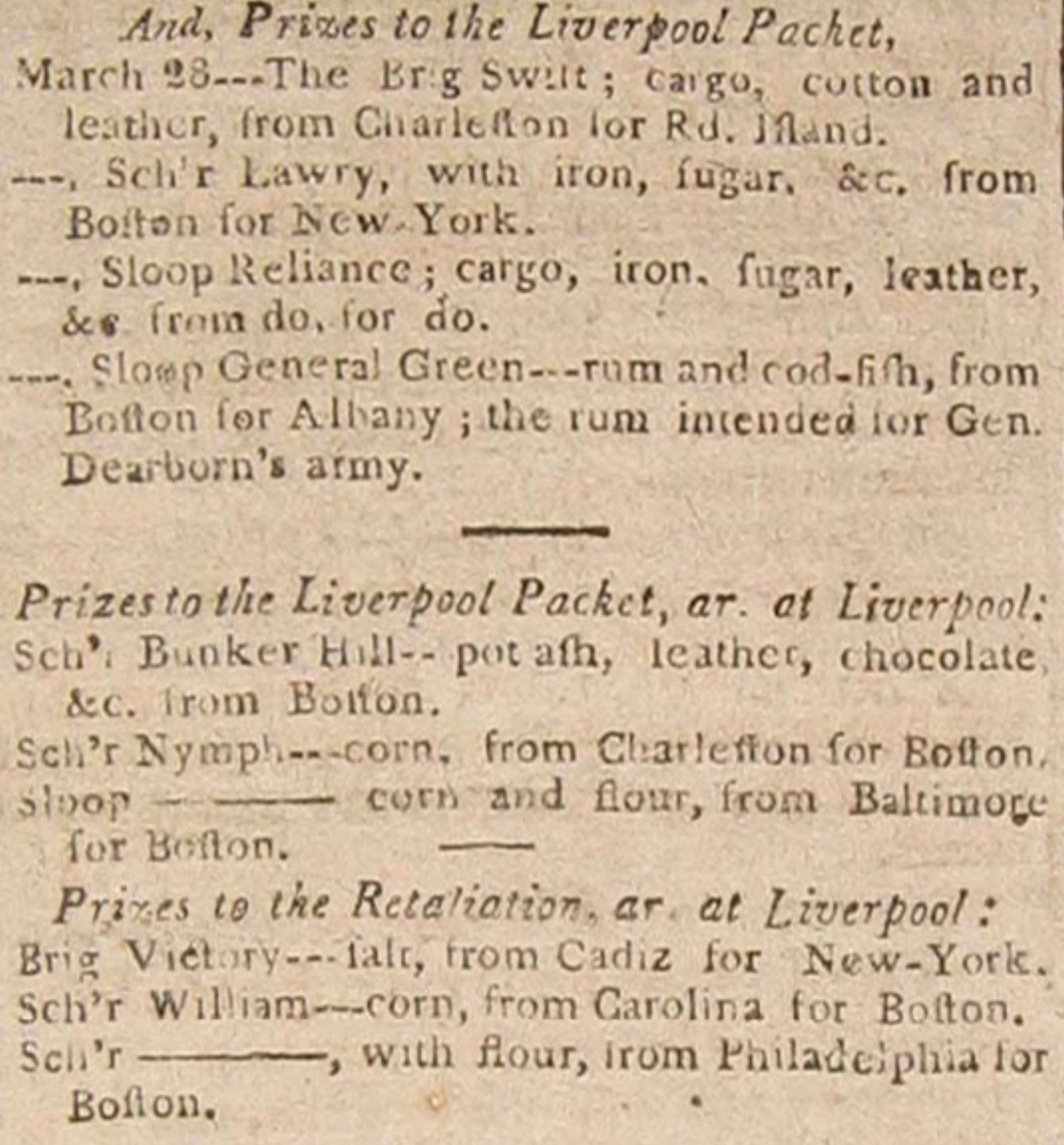

A list of prizes published in The Royal Gazette on March 31, 1813, includes four taken on March 28 alone: the brig Swift, captured while en route from Charleston, South Carolina, to Rhode Island with a load of cotton; the schooner Lawry with a load of sugar, iron and cotton bound for New York from Boston and the sloop Reliance, headed for an undetermined destination with iron, sugar, leather and cotton. It also captured the sloop General Green, destined for Albany, N.Y., from Boston with codfish and rum for the army of General Henry Dearborn, who later became a congressman and served as U.S. secretary of war.

Joseph Barrs, skipper of the schooner Liverpool Packet, was one of the great Maritime privateers. [Wikimedia]

The vessel’s owners were so inspired by Packet’s success, they bought the brig Sir John Sherbrooke, formerly the American brig-of-war Rattlesnake. With a displacement of 273 tonnes, the ship had 18 guns and was crewed by 150 men.

The vessel achieved the fastest success of any Canadian privateer, taking 16 prizes on its one and only cruise.

Already notorious, Packet had earned the nicknames New England’s Bane and The Black Joke, a moniker borne by several infamous slave ships, by the time it embarked on its third cruise, in April 1813.

Packet was three months out of port when its run of good luck took a turn: it came upon the American privateer Thomas out of Portsmouth, New Hampshire—twice Packet’s size, wielding 12 guns with a crew of 100.

By late winter 1813, Liverpool Packet larked off Cape Cod, taking vessel after vessel and in the process driving up marine insurance rates in Boston and other parts. The losses provoked outrage across New England. [Nova Scotia Archives]

“At 2 p.m., coming up with the chase very fast, the schooner hoisted her colours and commenced firing her stern chasers,” George E.E. Nichols wrote in the paper Notes on Nova Scotian Privateers.

“Overtaken by the American, she rounded to, struck her colours and ran alongside the Thomas. In the act of veering, she fouled the Thomas, and thinking their opponents about to board their vessel, the respective crews engaged in a hand-to-hand encounter.

“After striking her colours, the officers and crew of the Thomas repeatedly fired into the Liverpool Packet and threatened to give her crew no quarter. Greatly outnumbered, they were compelled to surrender, but not before several of the crew of the Thomas had been killed.”

Barss was taken to Portsmouth, where he was kept under armed guard for several months before Sir John Coape Sherbrooke, lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia and a former British army general, secured his release.

Liverpool Packet was converted into an American privateer and renamed Portsmouth Packet. But in October 1813, HMS Fantome, an 18-gun brig-sloop encountered the schooner off Mount Desert Island, Maine.

A chase ensued, lasting 13 hours before Fantome seized its quarry and brought the prize to Halifax. Packet was returned to her former owners, its Liverpool name restored. It resumed its plundering under the command of Caleb Seely.

Packet’s new letter of marque is now held in the Nova Scotia Archives.

Dated Nov. 19, 1813, it authorized Seely and his ship “to apprehend, seize and take, the Ships, Vessels and Goods, belonging to the United States of America, or to any persons being citizens of, or inhabiting within, any territories of the United States of America…according to His Majesty’s Commission.”As part of his privateering duties, Seely was ordered to take note of “the situation, motion, and strength of the Americans, as well as he can discover by the best intelligence he can get.”

Packet closed the year with 14 more prize vessels to its credit.

The ship had a successful 1814, too, capturing prizes in May and June, then taking two more alongside Shannon off New York and Bridgeport, Connecticut. Packet worked often with British naval vessels through the end of the war.

With hostilities over and privateering all but ended by the Treaty of Ghent and shifting Royal Navy policy, Packet’s owners sold it in Kingston, Jamaica. Its fate beyond that is unknown. A number of ships have since carried its name.

The vessel’s success helped launch the great fortune of its principal owner, Enos Collins, who would go on to found the Halifax Banking Co., which merged with the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 1903.

Born to a merchant family in Liverpool, he had sailed on a few privateering escapades to the West Indies in his youth. He was declared the richest man in Canada when he died in 1871 at the age of 97.

Advertisement