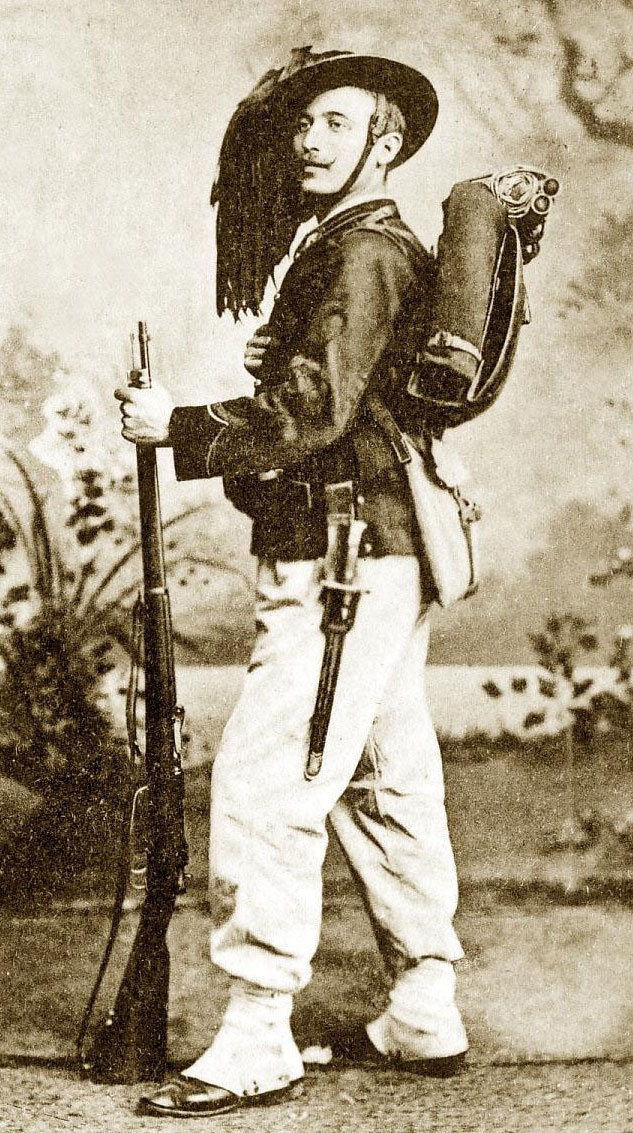

A soldier of the 8th Regiment of Hussars of France, circa 1804, wears a busby, a tall fur hat with a cloth flap and a feathered plume. [Wikimedia]

Celebrated officers wore the feathered crowns of egrets. British infantrymen wear “hackles.” Italian shock troops, known as Bersaglieri, rather flamboyantly sport the feathers of a particular wood grouse known as a capercaillie.

Military tradition has spawned a bizarre menagerie of headgear, both for dress occasions and battle. The practice is virtually as old as warfare. It knows no borders and, at times, it seems to defy logic.

The traditions have given birth to phrases such as “a feather in your cap” (an accomplishment one should be proud of) and “a brass hat” (a person of high position).

“Throughout history,” historian Michel Wyczynski wrote in a paper for the Canadian War Museum, “the headdress has been the most distinctive, varied and visible part of the uniforms of every country’s armed forces.

“For soldiers, the headdress was much more than an article of clothing. It was a symbol of their collective identity. The headdress reflected their unit’s cultural and ethnic legacies, esprit de corps, identity, pride, reputation and tradition.”

A Bersagliere with the Italian army sports the feathers of a capercaillie–a type of grouse–in 1900. [Lombardi Historical Collection/Wikimedia]

The war museum has more than 35,000 uniform-related items in its collection. Headdresses alone totalled 5,891 when an inventory was conducted in 1998.

Around 23 AD, Rome’s elite Praetorian Guard wore distinctive helmets with horsehair or feathered crests running front to back like a Mohawk hairstyle. High-status soldiers often supplied their own kit and decorated it to their own taste.

Some legionaries’ helmets had crest holders, with the crests made of plumes or horsehair, often dyed red, yellow, purple or black, and possibly in combinations thereof.

There is evidence, including sculptures from the time, that legionaries mounted their crests longitudinally and centurions wore them transversely. Early-empire centurions may have worn crests at all times, including in battle, but legionaries, and centurions during other periods, probably wore crests only occasionally.

In “The thin Red Line,” a painting by Robert Gibb, members of England’s Sutherland Highlanders face the Russian cavalry at the Battle of Balaclava in 1854. They are wearing feather bonnets. [Wikimedia]

The first berets as we tend to know them were adopted by members of the Royal Tank Corps in 1924. A wise choice for the cramped quarters of a tank.

They were black and armoured units have traditionally kept them that way—largely thanks to Field Marshal Viscount Bernard Montgomery of Alamein, whose black-bereted exploits in North Africa versus German rival Erwin Rommel are the stuff of military lore, and tend to be the go-to images of the bombastic Brit.

Wyczynski writes that the origin of the maroon colour for the British Airborne beret is documented at the Airborne Forces Museum in Aldershot, England.

Prince William, Duke of Cambridge, wears a busby as he rehearses for Trooping the Colour–a ceremony honouring the birthday of Queen Elizabeth II–in 2011. [Getty Images]

“It is believed that General Frederick “Boy” Browning, in accordance with this tradition, was given the honour of choosing a distinguishing colour for the newly raised division he was to command,” the airborne museum’s A.S. Brown wrote.

“His choice of the maroon colour is believed to come from the colour he used for horse racing silks.”

Berets usually bear a regimental badge but some highland regiments and others, such as the oversized caubeens of the Royal Irish Regiment, the Irish Regiment of Canada and the South African Irish Regiment, also sport a hackle, or feather.

The hackle is at the root of the expression “to get one’s hackles up” (to anger someone) which, according to The Canadian Oxford Dictionary, derives from “a long feather or series of feathers on the neck or saddle of certain birds” and not, in the military sense, one would assume, from Definition No. 2: “the erectile hair on the back of a dog’s neck.”

François-Isidore Darquier, officer of France’s Grenadiers of the Imperial Guard, wears a bearskin cap. [Wikimedia]

Preceding and in stark contrast to the beret, Scottish Highland infantry regiments adopted the feather bonnet in 1763, and wore it until the outbreak of the First World War, when the machine gun presumably rendered moot its protection against flailing swords.

They started as knitted blue bonnets with checkered borders, propped up and worn with a tall hackle.

Seventeenth-and 18th-century Highlanders added ostrich feathers, first to decorate their bonnets, then entwining them into a lightweight cage that served to protect against blows and provide ventilation.

Highland regiments stationed in North America between 1760 and 1790 are believed to have adopted some of their decorative practices from the traditions of aboriginal peoples, whose feathers were awarded for successes in battle.

Again, different regiments had different coloured hackles: the Black Watch had red, not black; and in what might be considered an odd choice for an army, the Seaforth Highlanders, Gordon Highlanders, Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders and Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders all had white hackles.

Horatio Nelson, 1st Viscount Nelson, after the Battle of the Nile. Artist Lemuel Francis Abbott painted the chelengk–a jewelled headdress ornament–with seven rags instead of the actual 13, each representing the 13 French ships Nelson destroyed at Alexandria in 1798. [Wikimedia]

The famously diminutive French were apparently imitating the Prussians in attempts to add the impression of height and thus better intimidate their enemies in battle. It may have worked for a while. But bearskin caps proved expensive and demanding to maintain, so during the 19th century they gradually became limited to guardsmen, bands and other ceremonial units.

The British Foot Guards and Royal Scots Greys wore bearskins in battle during the Crimean War and on peacetime maneuvers until 1902, when they switched to khaki service dress.

The English had their own name for the ostentatious Hungarian fur shako, or kucsma. They called them busbies—a military headdress made of fur.

The Hungarians’ cylindrical fur cap had a bag of coloured cloth hanging from the top with the other end attached to the right shoulder as a means to deflect slashing sabres. The headgear was widely worn in the armies of Britain, Germany, Russia, Netherlands, Belgium, Bulgaria, Romania, Austria-Hungary, Serbia, Spain and Italy.

The origin of the name busby is murky but it is known that the hatter who supplied the officer’s version of the British hussar cap of the early 19th century was named W. Busby of the Strand, London.

Australia’s Queensland Light Horse adopted emu feathers in the early 1890s. The distinctive feathers quickly became associated with Australians in general and other Aussie regiments felt compelled to copy them—reluctantly so, in many cases.

A replica of Nelson’s chelengk. The original was stolen from Britain’s National Maritime Museum at Greenwich in 1951 and never recovered. [Britain’s National Maritime Museum Collection]

As if the hat alone weren’t enough, bicornes would often sport a çelenk (chelengk), or feather, derived from Turkish tradition. Originally attached to turbans as a sign of bravery, they were instituted by the Ottomans as awards for military merit until the 1820s.

They typically were or at least represented the tufted crest or head-plumes of the egret, known in French as “aigrettes”—often jewelled representations consisting of a central flower from which rays extended upward.

Sultan Selim III awarded a specially made chelengk to Nelson after the Battle of the Nile in 1798. It was the first time one was conferred on a non-Ottoman.

A caubeen of the Royal Irish Regiment. [Royal Irish Virtual Museum]

Nelson’s chelengk, inaccurately depicted in 18th century artist Lemuel Francis Abbott’s portrait of the British icon, was stolen from Britain’s National Maritime Museum at Greenwich in 1951 and never recovered.

The bicorne was typically worn fore-and-aft in most armies and navies from about 1800, though French gendarmerie continued to wear theirs side-to-side until about 1904, and the Italian Carabinieri still do.

Officers of many if not most of the world’s navies wore the bicorne as part of their full dress until the First World War. Senior officers in the British, French, American, Japanese and other navies continued the tradition until the Second World War.

It has pretty much vanished since.

Advertisement