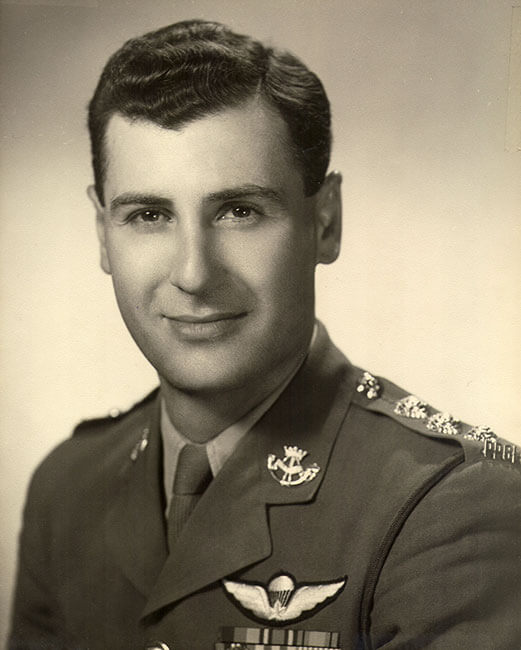

Lieutenant Mike Levy in 1952. [The Military Museums]

Everyone, that is, except Lieutenant Mike Levy, a platoon commander who, within earshot of the enemy battle cry, decided to respond.

“We are Canadian soldiers,” retorted the young subaltern in the appropriate Chinese dialect, “we have lots of Canadian soldiers here.”

Born in the Indian city of Bombay (present-day Mumbai) in 1925, Levy, the eldest of four siblings, had already lived an eventful life in the years prior to the Korean War. At an early age, his British father moved the family to Shanghai, where Levy developed an eclectic interest in sports.

At just 16, he endured his first taste of conflict when the Japanese invaded and occupied Shanghai in 1941. He was subsequently placed in Lunghua Civil Assembly Camp—since immortalized by Steven Spielberg’s 1987 epic Empire of the Sun. Yet he had no intention of spending the entire war imprisoned.

Levy’s chance for escape came on the night of May 22, 1944. Together with four comrades, he staged a successful breakout and, for about two months, evaded Japanese authorities as the group embarked on a 3,200-kilometre journey through occupied China to India.

There, due to his knowledge of Chinese culture and language, Levy soon found himself recruited by the British Special Operations Executive. Serving in the so-called Force 136, he achieved the rank of captain while engaged in guerrilla-style warfare of sabotage and espionage behind enemy lines.

One engagement in Malaya resulted in Levy receiving a Mentioned in Despatches. His commanding officer described him as a “young chap, full of guts.”

Lieutenant Mike Levy and the 10th Platoon in Korea in 1951. [The Military Museums]

The Chinese Fifth Phase Offensive had launched, and the South Korean defenders, despite being supported by the Kiwi artillery, were breaking.

Before Kapyong, however, the then-retired soldier moved to Vancouver and became a restaurateur. His fighting days appeared over until June 25, 1950, when Kim Il Sung’s North Korean forces invaded South Korea.

Levy, who previously served with the militia, volunteered for Canada’s hastily created Special Force. He joined 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (2 PPCLI), at the rank of lieutenant.

By April 22, 1951, Lieutenant Mike Levy, as 2 PPCLI’s 10 Platoon commander, was in reserve with the rest of 27th British Commonwealth Infantry Brigade. The UN force, comprising mostly of Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders, Indians and Brits, had been relaxing around the Kapyong valley when they heard word that the Chinese Fifth Phase Offensive had begun. They learned that the South Korean defenders, despite being supported by the Kiwi artillery, were in the process of breaking.

With 3rd Battalion, the Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR) occupying Hill 504 to the east of the Kapyong valley, 2 PPCLI established itself on Hill 677 to the west. Nightfall on April 23 brought the first Chinese assaults against the Australians, who fought valiantly well into the next day until it became clear that their position was untenable. Their subsequent withdrawal over the 24th meant an enemy attack against 2 PPCLI was now all but inevitable.

It was under these circumstances, facing repeated communist waves amid the Canadian defence of Hill 677, that Levy earned a new reputation.

Lieutenant MIke Levy being treated for a shrapnel wound in Korea in 1951. [The Military Museums]

Knee-deep in the maelstrom was Levy’s 10 Platoon. A cool and charismatic leader at the best of times, he recognized the perilousness of ‘D’ Company’s situation as the Chinese continued to overwhelm the immediate area.

Levy’s following gamble, which he proposed to company commander Captain Wally Mills, was a momentous one. He requested that 16th Royal New Zealand Artillery Regiment fire on top of his own beleaguered sections. Mills relayed the message over the radio. Meanwhile, Levy told his men to hunker down.

Shortly thereafter, the Kiwis’ 25-pounders rained hell upon the Canadian defences—and the enemy soldiers within the perimeter. Shells fell a mere five or six metres from 10 Platoon. Simultaneously, Levy maintained constant radio contact with the New Zealanders and helped direct the bombardment.

When not leaping from slit trench to slit trench encouraging his men and honing artillery fire, Levy traded insults with the attackers. Agonizing screams soon filled the air as shrapnel bursts scattered just beneath the tree-tops to shred the Chinese ranks. Slowly but surely, the communist waves began to falter.

Finally, with dawn breaking on the 25th, the Chinese assaults petered out. The Canadians, though shaken and wounded, raised their heads to see who was still alive. Not one defender had died in the allied artillery strike.

Overall, the Battle of Kapyong cost the Canadians 10 killed and 23 wounded. Their action would eventually be recognized with a shared U.S. presidential citation. Additionally, several valour awards, including a Military Cross for ‘D’ Company’s Captain Wally Mills, were presented. Levy received no equivalent acknowledgement for his heroism.

This often-perceived oversight remains one of the great mysteries of Kapyong, since few deny the significance of his contribution. At one of the most desperate moments of the battle, Levy, who died in 2007, had the strength to gamble—and it paid off.

Advertisement