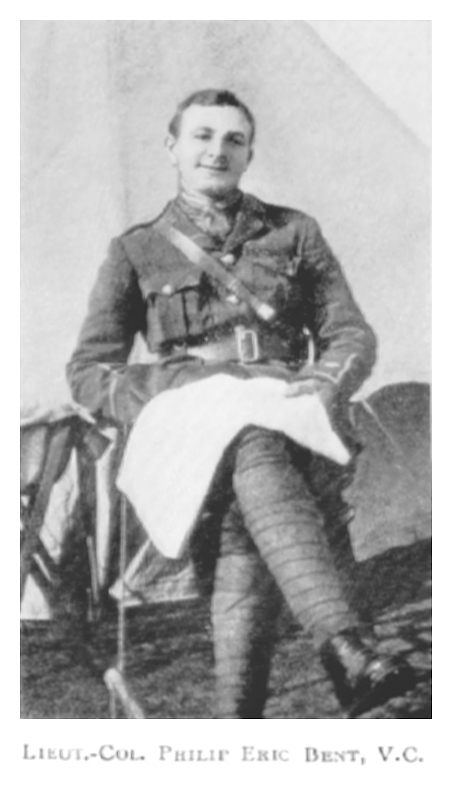

Lieutenant-Colonel Philip Eric Bent during the First World War. [Wikimedia

“They said he was a disciplinarian when he got into higher rank, but he was well-liked by his men, well-respected,” historian Kenneth Hillier, who authored a book on Bent’s life, told CBC.

Even so, war knew no mercy, and on Oct. 1, 1917, Bent was killed while leading a counterattack against the Germans at Polygon Wood, Belgium, during the Battle of Passchendaele. His exemplary acts, however, were solidified not only as a British soldier, but as a Halifax legend with bootstrapping charm.

“Philip Eric Bent, although he served in the British Army, is always considered a Canadian,” wrote the Halifax Military Heritage Preservation Society (HMHPS). “Bent was the only officer from Nova Scotia to earn the Victoria Cross and the first Atlantic Canadian to be awarded the VC posthumously.”

Leicestershire Regiment near Ribécourt, France, during the Battle of Cambrai on Nov. 20, 1917. [Wikimedia]

His skills were undeniable.

Born on Jan. 3, 1891, Bent lived in Halifax until the age of 12, when he moved to Scotland to attend Ashby Boys Grammar School. There his peers noticed he was a cut above the rest.

“A schoolmate described him as a live wire,” Hillier told CBC.

Starry-eyed for nautical adventure, Bent joined HMS Conway in 1910, a “school ship” where he received two-years’ naval training. He was a qualified merchant navy officer by the time the First World War broke out.

Still, Bent wanted to a new adventure and experience, and he and a friend joined the Royal Scots on Oct. 2, 1914, hoping to see a little army action before Christmas—what they believed would be the war’s end.

His skills were undeniable, with recruiters stating “had [we] known of his nautical qualifications … [he] would have been commissioned into the navy.”

Regardless, Bent joined the Leicestershire Regiment a month after enlistment. Moving up the ranks, he eventually commanded the unit in the spring of 1917 as it attempted to break through the Hindenburg Line. He received the Distinguished Service Order in June for his “devotion to duty.”

Later that year, however, would come his greatest military challenge: the Battle of Passchendaele.

The Germans, masked by a thick smokescreen, initiated a heavy artillery barrage.

Beginning on July 31, 1917, the British army faced little resistance during the offensive’s initial weeks, capturing villages clustered around Ypres. But while the German enemy was one thing, the weather was another.

Soon torrential downpours turned the area into a muddy death trap.

“Mingling with soil and clay,” the HMHPS wrote, “it dragged hundreds of heavily laden or wounded soldiers to their deaths as they struggled across the stinking ooze.”

Meanwhile, the German line remained steadfast throughout August, delaying the Brits’ expected breakthrough while inflicting 70,800 casualties.

In late-September, the British regrouped and refitted before resuming their attack. They captured Polygon Wood on Sept. 30, with the 8th Battalion taking the left side of the 110th Brigade and Bent’s 9th Battalion taking the right.

“Though we had fully prepared for a rough night, the first hours passed quietly enough and we began to hope that after all, the Ypres bark might be worse than its bite,” remarked D.A. Bacon, one of Bent’s officers.

The units then dug in, and made miserable attempts at sleep amid the layers of cold sludge.

Still, they were in for a rude awakening. The next morning at 4:40 a.m., the Germans, masked by a thick smokescreen, initiated a heavy artillery barrage. As the assault persisted past dawn, the units called the brigade headquarters for help. Bent answered.

Enlisting the help of a reservist platoon and other companies, he organized and led a counterattack against the Germans, whirling his revolver while shouting “Come on the Tigers!”

Bent’s charge was a success, securing a portion of the line. Bent himself, however, wasn’t so lucky. He was killed by an enemy bullet in the melee.

“It was the most glorious end to a brilliant career. Believe me,” an officer wrote in a letter to Bent’s mother, Sophy.

She received her son’s Victoria Cross for his actions at Passchendaele from the King at the Buckingham Palace on his behalf.

Advertisement