Illustration by Kerry Hodgson

It was June 1940, and the Maginot Line had been outflanked. French and British troops had failed in their attempt to stop the German advance toward Paris. From the skies, German bombers unleashed deadly cargo while, in an effort to flee France’s capital, desperate refugees in cars, on bicycles and on foot clogged roads leading to the coast and to relative safety.

Among these hordes was Gladys Arnold, the only accredited Canadian journalist to witness first-hand the fall of Paris and France. She had managed to escape the French capital by car in the grey dawn of June 12, only one day before the Nazis invaded the city.

Years after the fact, Arnold vividly recalled one of the nights during which she was a refugee.

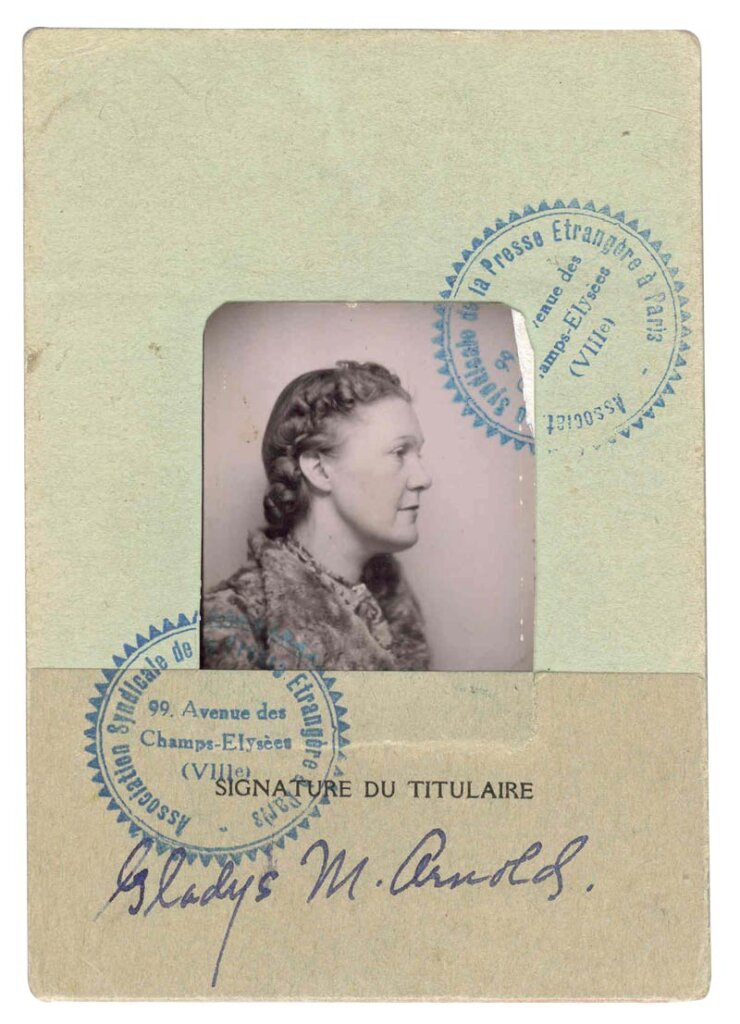

Gladys Arnold was the only Canadian journalist in Paris as the city fell to the Germans in June 1940.[University of Regina Library]

“Just before midnight a great wave of German bombers came over,” she wrote in her memoir One Woman’s War. “They were dropping flares…. Voices screamed. There were sounds of people fighting, of smashing blows. It was bedlam in the dark. People somehow found space to cower by the road or against the walls. A space opened before us as people moved aside to seek shelter.”

In the five days she was on the road, this intrepid, determined young woman used scraps of paper to record interviews with displaced French, Belgian and Dutch people. She attempted to mail these stories, but with the country’s government and infrastructure collapsing, her efforts were in vain. None of her articles reached its destination.

When conducting her interviews, Arnold never heard a defeatist word among the “ordinary people” where, according to her, the true French spirit lived, not in their trusted military and political leaders, whom she labelled the real defeatists. It was, claimed Arnold, an experience that changed the course of her life.

But even by the age of 35, this woman had led a remarkable existence. In fact, she had already overcome many challenges to reach this stage of her celebrated career, one that was partly shaped by her early years.

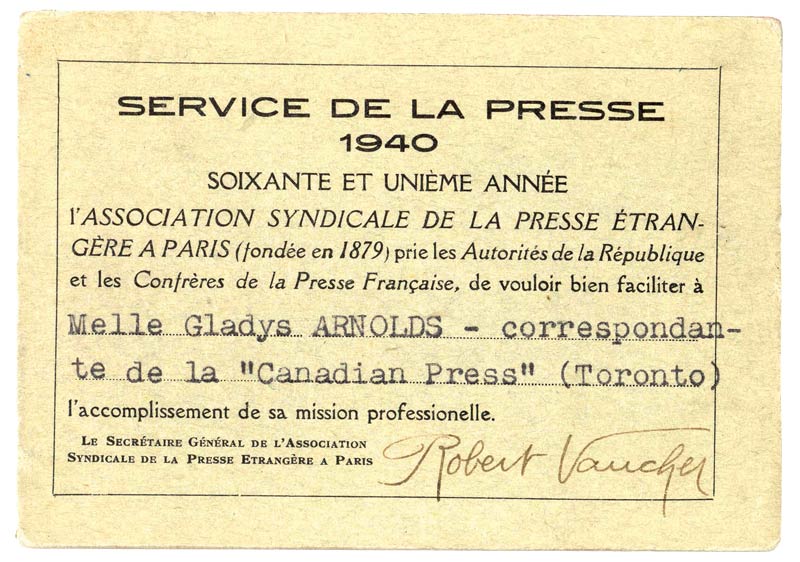

Gladys Arnold’s French press credentials. [University of Regina Library]

Gladys Arnold was born in a small Saskatchewan town, Macoun, in 1905, the year the province was created. The first child of Albert and Florida May Arnold, she led a nomadic existence in her early years since her father’s job as a Canadian Pacific Railway troubleshooter required that he frequently move his family from one town or city to another.

Further uprooting occurred after his untimely death in 1914. Arnold’s mother left her daughter in the care of relatives and moved east with her son Max, Arnold’s only sibling, to study nursing. Because of all this upheaval, Arnold attended at least a dozen different schools before she graduated high school.

Her father’s passing when she was only nine years old and the resulting breakdown of the family unit affected Arnold deeply, wrote Joanna Leach in her 2008 master’s thesis in history, “Gladys Arnold: The formative years.” Not only did Arnold come to depend on herself and her own abilities to make her way in the world, but the loneliness and lack of love she felt after her mother’s departure led her to seek solace in books and writing.

This eventually led to a career in journalism. The job would satisfy her abiding curiosity about the world, an inquisitiveness that would be expressed in the pledge she made in 1929 to “someday see every country in the world, get everything out of every day, live in the pursuit of all my life and there make my future.”

“Just before midnight a great wave of German bombers came over. Voices screamed. There were sounds of people fighting, of smashing blows. It was bedlam in the dark.”

But before she entered journalism, Arnold obtained a teaching certificate in 1925. This led to a job at a schoolhouse in the remote village of Amulet, then at other rural villages in Saskatchewan. Her teaching career ended when she moved to Winnipeg to study at Success Business College. After graduating she taught shorthand at the school for a year before jumping at the opportunity to become secretary to the editor of Regina’s Leader-Post in 1930. Although she lacked any formal journalism training, it wasn’t long before she was promoted to reporter, a significant achievement in a male-dominated profession that was traditionally patriarchal and very resistant to change.

Four years later, Arnold was promoted to women’s editor and began writing a column. In it, she covered traditional women’s topics, but she also attempted to broaden the horizon of her readers by discussing arts and cultural events in Regina, suffrage, socialism and pacifism, as well as international developments such as the rise of fascism in Europe. Her priorities weren’t shared, however, by her editor Bob MacRae, who, in a letter, informed her, “Only a fraction of our readers get het [sic] up about economics and foreign policy…they are more concerned with love, food, the movies, clothes and family affairs.”

In the five years that she spent at the paper, Arnold honed her journalism skills and acquired a better understanding of herself and her goals. While doing so, she became more convinced than ever that she wanted to advance in areas hitherto largely reserved for male reporters and to satisfy her curiosity about developments in Europe.

So, in 1935, Arnold left the Leader-Post and headed for Paris. In her memoir, she described the reasons for this move.

“As a young reporter with the Regina Leader-Post, I had gone to Europe in 1935, intending to stay for a year or so. My reason for going can be boiled down to two words: political curiosity.

Living through the drought and unemployment of the Depression in Saskatchewan, those of us in our twenties passionately debated the pros and cons of socialism, communism, fascism and democracy, searching for answers as to why more than a million Canadians could not find a job,” she wrote. “In Saskatchewan it was difficult to examine these isms first hand. But in Europe surely we would find some answers.”

Arnold grew to love Paris and its people and, in the four years she spent there, she learned French and immersed herself in the culture. Initially, she submitted freelance articles with a Canadian angle to the Canadian Press (CP), as well as to newspapers in Western Canada. In 1936, CP hired Arnold as its Paris correspondent (for $15 per week). During this period, she reported from France, Belgium, Austria, Germany, Czechoslovakia, Switzerland, Italy, Hungary and from the Spanish border during the civil war there.

However, in August 1939, with war threatening, Arnold sailed home to Canada to visit her family.

“I had been homesick for the sight of the big night sky and the golden haze of windborne chaff, and for the smell of wheat baking in the sun,” she wrote.

With the eruption of the Second World War, Arnold realized she had to return to Paris. “Staying home,” she recalled, “would be like leaving a theatre just after the curtain rises and the main characters are identified.” Determined to see the conflict between fascism and democracy first-hand, she left Canada for France in mid-October.

Back in Paris, she found accommodation at the Foyer International and from this cozy residence she spent time searching for stories during what was then the so-called Phony War. Although she, like other journalists, yearned to visit the Maginot Line, the front or the naval bases, she was ordered by CP to “stick to human interest stories.” The boys in the London bureau would look after the political and military ones.

Perhaps unwittingly, however, the national wire service gave her what she considered to be the real story. This entailed reporting on what the troops were eating and how the French army managed to feed 200,000 troops at one supply station every day. She also went on expeditions to witness French women at work, running farms, driving buses, staffing factories and doing jobs that had previously been done by mobilized men. It was while she was dispatching stories such as these to CP that she learned of the Germans’ imminent arrival in Paris and the need to escape France.

Leaving the country that so enchanted her for England, then Canada, after the fall of Paris was exceedingly difficult, both emotionally and physically. There was not only the wrenching departure from friends, but also the hardships endured on the perilous voyage from Le Verdon, France, to Falmouth, England.

Along with the constant fear the small cargo ship she sailed on might be sunk at any moment, there was the physical discomfort endured by the vessel’s passengers, including more than 300 refugees and over 20 wounded British soldiers.

When the ship’s Dutch captain spotted Arnold’s typewriter, he asked her to record the names and addresses of all passengers as, should the vessel be torpedoed, there was only a handful of lifebelts and boats available. The list included the names of several political figures.

After the ship’s safe arrival at Falmouth, Arnold made her way to London, where she succeeded in getting an interview with General Charles de Gaulle, the leader of the Free French, the French military and civilian forces outside mainland France. He left a lasting impression on her.

“I was surprised by his great height, his grave and thoughtful mien and the warmth of his keen eyes,” she said. “As he welcomed me, his voice was soft and his manner touched with old-world courtesy.”

So captivated was Arnold by de Gaulle that she blurted out: “Is there a place for me in your volunteer army?” Whether she realized it or not, this offer foreshadowed a new direction her life would soon take: a career serving France with the Free French.

As the young general didn’t have even one tank at his disposal, let alone any troops, Arnold decided she would remain in London chasing war-related stories. The Canadian Press, however, had different ideas. It wanted her back in Canada and, in August 1940, it arranged for her to return on a ship carrying British youngsters destined for new lives in her homeland. Arnold was asked to report on the crossing and the children’s reaction to it.

Back in Canada, Arnold did follow-up stories about the children, along with other assignments for CP. The thought of serving the Free French cause, however, continued to consume her and, in July 1941, she resigned from the Canadian Press and set about helping establish the Free French Information Service in Ottawa. She became director of the organization when it was attached to the French Embassy postwar.

Arnold retired in 1971. Four year later, she was named Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur for her service to France, a recognition that followed her nomination as honorary brigadier in the French Free Forces in 1940.

The former small-town prairie girl, resourceful and courageous journalist died in 2002 in Regina.

Advertisement