Syrians celebrated their liberation from Assad’s repressive and corrupt government. But the country’s future remains uncertain.

[Atlantic Council]

Syrians were jubilant. An exploitive and ruthless regime had been deposed. Censorship, surveillance and repression were apparently stopped. Exiles returned. Political prisoners were freed. The prospect that Syria, the third most-sanctioned country, could reclaim its place in the world suddenly seemed attainable.

Thirteen years after the bloody Arab Spring launched the war, there was dancing in the streets. But now the questions: who are the victors and what are their priorities?

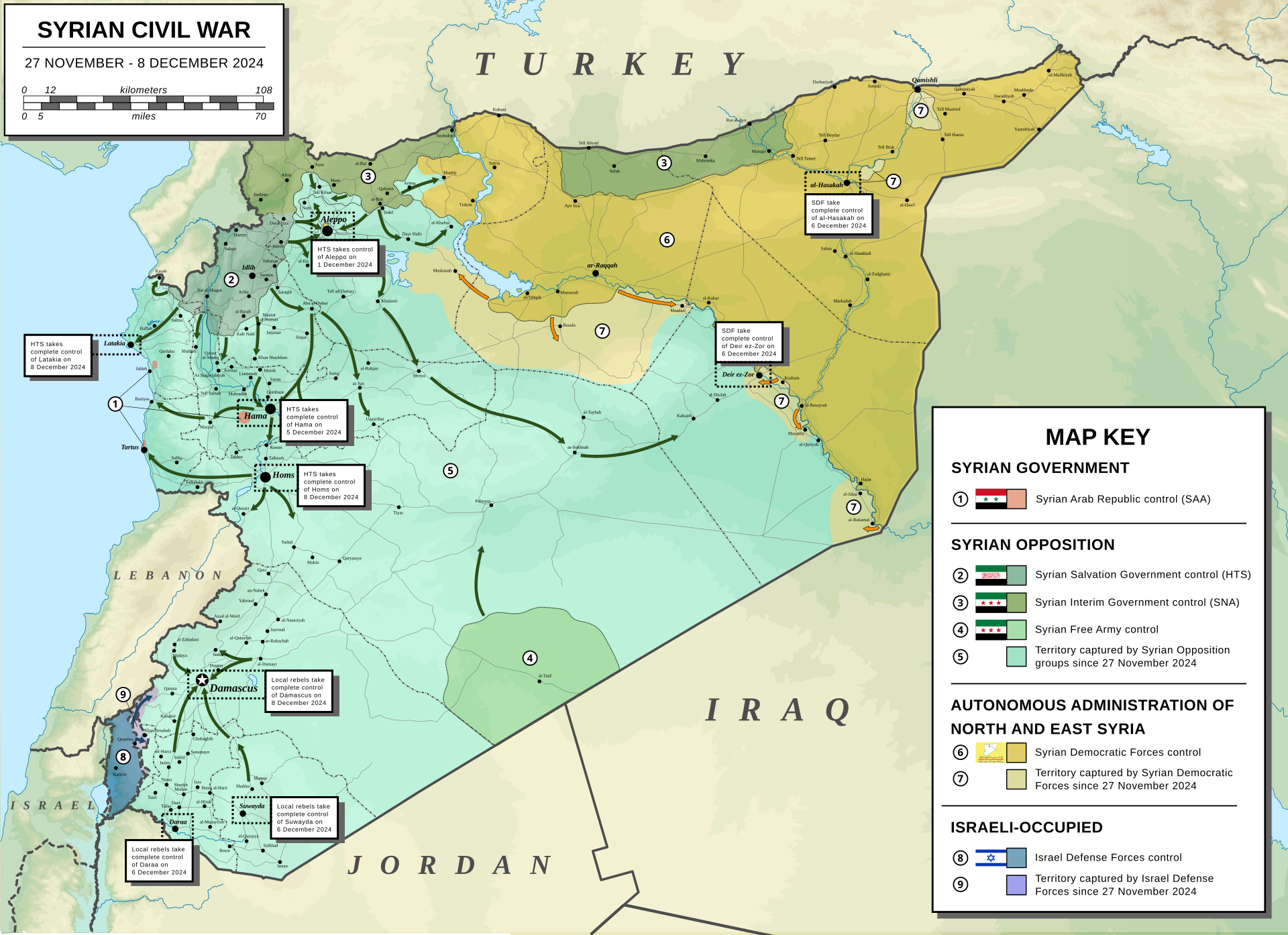

They now call themselves the Salvation Government.

An enemy of both sides, the Islamic State group (a.k.a. the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria—IS, or ISIS) was eliminated from the multifactional fighting in 2017, squandering significant territorial victories. But analysts warn it remains a factor.

The primary rebel commander, Ahmed al-Sharaa—better known as Abu Mohammed al-Golani—is a former al-Qaida chief and designated terrorist. He severed ties with al-Qaida in 2016 and rebranded his faction in a more moderate image. Golani has vowed to rebuild a Syria gutted by decades of corruption and devastated by war.

He and his Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), the leading force in the lightning offensive, have been running a conservative regime in the northern border province of Idlib, populated by close to three million people, of whom almost 900,000 are considered internally displaced.

“It is an effective fighting force but with jihadist roots and al-Qaida baggage,” foreign policy expert Aslı Aydıntaşbaş wrote for the Brookings Institute, adding it “cannot dominate the diverse political and sociological tapestry of Syrian society—and luckily its leader…seems to understand that.”

Also sharing in the victory are U.S.-allied Kurds and Turkey-backed Sunni Arabs, who have been at the head of separate enclaves in northern Syria.

“They now need to show political and ideological flexibility to be part of an inclusive interim governance project in Damascus,” said Aydıntaşbaş. “Curbing the influence of Islamists will not be easy, but their inclusion in the political process and the specter of elections within a year, as well as Ankara’s influence, could have a moderating impact.”

“Millions of Syrians now have a chance to return home.”

Assad’s defeat is also the strategic defeat of Russia and Iran in the region, she wrote. She called it a setback for Gulf Arab monarchies that had been trying to normalize the Assad regime after readmitting it to the Arab League in May 2023.

Now, says Aydıntaşbaş, they stand to lose political influence, as Turkey, a long-time backer of the Syrian rebels, stands to gain.

“But for Syrians, the hard work starts now,” she added. “The opposition forces inside and outside the country have some experience in governance, but they do not know how to govern in harmony with one another. “

In the end, she predicted, “Syria will not be worse than what it was.”

“Millions of Syrians now have a chance to return home and provide a balance against armed militia groups and radicalism,” wrote Aydıntaşbaş.

“The West will continue to have an interest in Syria, not only in fighting an Islamic State resurgence but also in staying engaged to guarantee Israel’s security, ward off extremism, and help the country’s evolution.”

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu claimed credit for Assad’s defeat. He declared it a turning point in the Middle East, saying it was a “direct result of the blows we inflicted on the main supporters of the Assad regime.”Professor Yossi Mekelberg, a senior consulting fellow at the international affairs think tank Chatham House, warned against premature conclusions about the region’s future, however, telling The Independent: “Netanyahu would like to take credit for everything except the things which have gone very, very wrong.”

Mekelberg told the newspaper that Israel’s actions had “weakened Hezbollah” and disrupted Iran’s supply lines, which emboldened Syrian rebels to challenge Assad’s regime. But he added the future remains uncertain.

“When a regime of 54 years has completely shuttered and gone, 48 hours later any prediction would be almost irresponsible,” he said. No one knows who is going to control Syria, he added.

“Hundreds of air strikes have rocked Syrian military sites, destroying most of the major capabilities of the new Syrian state to protect itself.”

At The Nation, America’s oldest continuously published weekly magazine, writer Séamus Malekafzali warned that celebrations in Syria might be premature.

He said the speed of the Assad dictatorship’s collapse stunned even the opposition. The result is a power vacuum that Israel and Turkey are already moving to occupy.

“Another dark cloud is gathering,” he wrote four days after Damascus fell. “Israel has publicly responded to the sudden fall of Assad with a contradictory mix of celebration and military invasion. In reality, Israel sees, and is taking, an opportunity to seize more Syrian land. Israeli troops have moved quickly into the UN buffer zone in the Golan Heights, claiming to want to protect settlers from instability in Syria.

“Hundreds of air strikes have rocked Syrian military sites, destroying most of the major capabilities of the new Syrian state to protect itself. Already, far-right figures close to…Netanyahu are speaking of the need to settle in this new territory, to never leave, and to assert Israeli sovereignty.”

Netanyahu himself, added Malekafzali, has emphasized when speaking English that that this would be a “temporary defence position.” When speaking in Hebrew to an Israeli audience, he reports, the Israeli PM gave no such assurances.

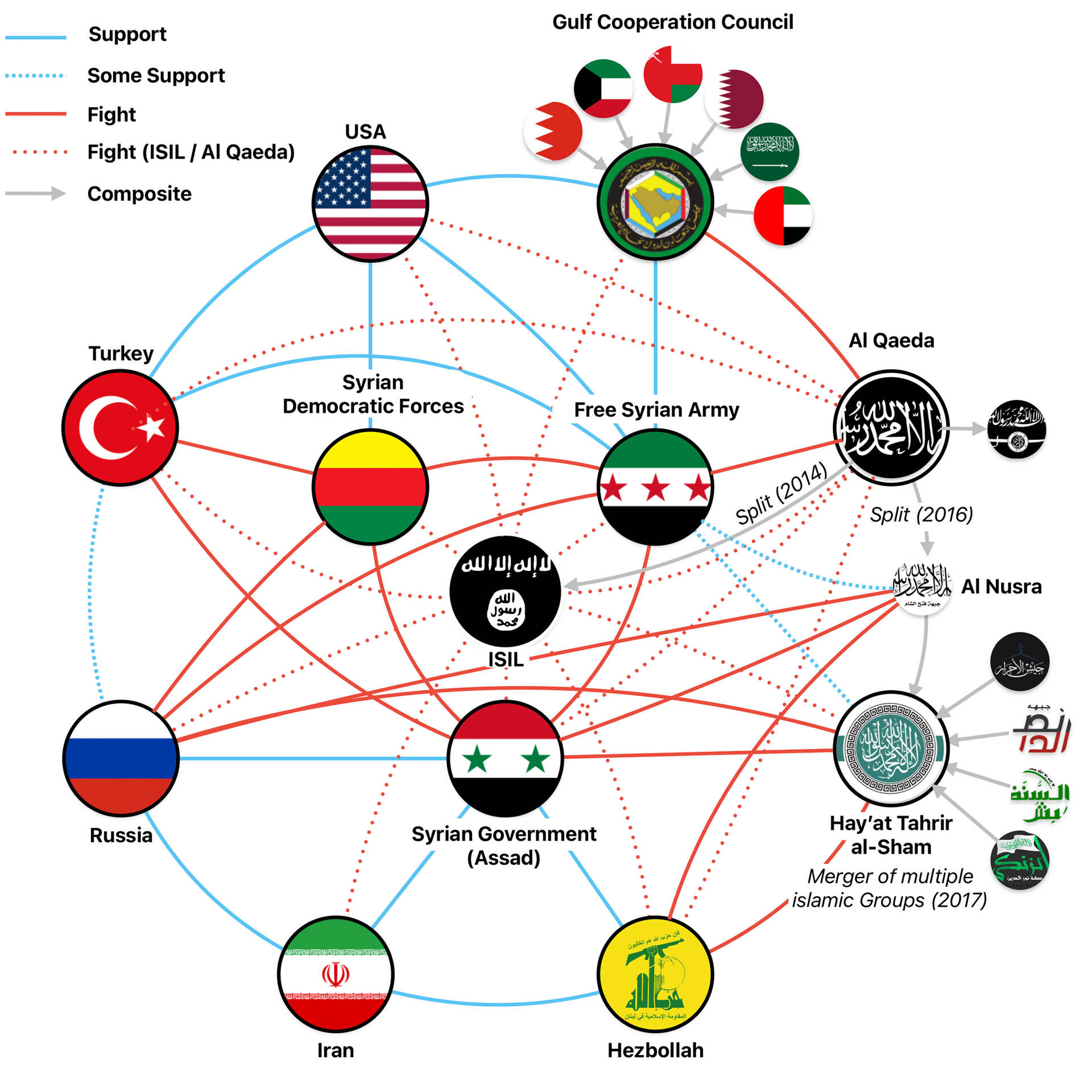

Multiple local, regional and international actors were involved in the Syrian civil war prior to the fall of the Assad regime.

[Wikimedia]

“Perhaps HTS does not want to engage in a military conflict with Israel so quickly after achieving victory,” Malekafzali wrote. “Perhaps it hopes that Israel will be satiated once it finishes destroying the remnants of Syria’s military capabilities.

“Perhaps it does not want to bite the hand of the country whose war against Hezbollah undoubtedly paved the way for its march into the presidential palace. Perhaps it hopes that a country that once pragmatically supported the opposition in the south could pragmatically support it again.

“Regardless,” he said, “once the euphoria wears off, and the joy of achieving power wanes, the Salvation Government may learn that the fires Israel starts are not put out easily.”

“Roughly 30% of the country is controlled by opposition forces.”

The war traces its origins to March 2011, when popular discontent with Syria’s Ba’athist government led to large-scale protests and pro-democracy rallies across Syria, part of the wider Arab Spring protests that swept the region.

Protests were violently suppressed by security forces in Assad-ordered crackdowns that resulted in tens of thousands of deaths and detentions, primarily of civilians.

The Syrian revolution transformed into an insurgency with the formation of resistance militias across the country, deteriorating into a full-blown civil war by 2012.

Iran, Russia, Turkey and the United States have all provided support to opposing factions. Iran, Russia and Hezbollah support the Syrian Arab Republic militarily. Russia has even mounted airstrikes and ground operations since September 2015.

The U.S.-led international coalition has been conducting air and ground operations since 2014, primarily against the Islamic State and sometimes against pro-Assad forces. It has militarily and logistically supported factions.

Turkish forces have occupied parts of northern Syria and, since 2016, have fought pro-government forces while actively supporting the nationalist faction known as the Syrian National Army.

Between 2011 and 2017, the fighting spilled over into Lebanon, and Israel has exchanged border fire and conducted repeated strikes against Hezbollah and Iranian forces, whose presence in western Syria it views as a threat.

Frontline fighting had mostly subsided by 2023, though there were regular flare-ups in northwestern Syria and large-scale protests in southern Syria. The protests spread nationwide over extensive autocratic policies and the economic situation.

By early 2023, the United States Institute of Peace was reporting “the conflict appears to have settled into a frozen state. Although roughly 30% of the country is controlled by opposition forces, heavy fighting has largely ceased and there is a growing regional trend toward normalizing relations with the regime of Bashar al-Assad.”

On Nov. 27, 2024, however, rebels launched a lightning offensive in northwest Syria. They seized 13 villages, including the strategic towns of Urm Al-Sughra and Anjara. Base 46, the regime’s largest in the region, also fell.

Rebel forces entered Aleppo on Nov. 29. Several more settlements were seized on the 30th. They reached the outskirts of Damascus on Dec. 7. Iranian foreign minister Abbas Araghchi attributed the rebel victory to the fact “the Syrian army refrained from putting up any resistance.”An estimated 219,223–306,887 civilians were killed and some 6.7 million people internally displaced; another 6.6 million left the country.

Military/rebel deaths totalled between 580,000 and 617,910; 219,223-306,887 civilians were killed and some 6.7 million people internally displaced; another 6.6 million left the country.

“Over the last decade, the conflict erupted into one of the most complicated in the world, with a dizzying array of international and regional powers, opposition groups, proxies, local militias and extremist groups all playing a role,” concluded the peace institute, a U.S. federal institution tasked with promoting conflict resolution and prevention worldwide.

“The Syrian population has been brutalized,” it added in a March 2023 report, citing civilian deaths and displacements, widespread poverty and hunger, a cholera outbreak, catastrophic earthquakes, a collapsing economy, and “humanitarian suffering…at an all-time high.”

Advertisement