Newfoundlanders at the their camp known as the “Beothuk,” in the south of Inverness, Scotland during WWII. [Bob Clarke/NOFU.ca]

The reason was simple: too few loggers to meet increased demand.

A widespread absence of wooden frames to literally and figuratively prop up the nation’s coal-mining industry proved to be the most pressing challenge. Without that infrastructure in place, such a critical part of the war effort was under threat.

Aside from re-establishing the Canadian Forestry Corps, which had contributed an estimated 70 per cent of Allied lumber during the First World War and beyond to 1920, Britain needed more production.

So, it looked to the resource-rich, economically poor Dominion of Newfoundland for help.

In November 1939, Britian asked the former self-governing Island for 2,000 men “capable of good work with axe and hand saw” to be sent across the pond.Within two-months, 2,150 volunteers between the ages of 18 and 55 were selected to form the Newfoundland Overseas Forestry Unit (NOFU). By 1940, a total of 3,600 Newfoundland loggers would work from southern England to the Scottish Highlands, spanning 30 logging camps in 25 different forests.

The initial draft of 350 men, contracted for six-months of 44-hour labour weeks, sat sail from St. John’s, Nfld., to Liverpool on Dec. 13, 1939. The remainder would join them by mid-February, after logistical challenges created a slow start for the unit.

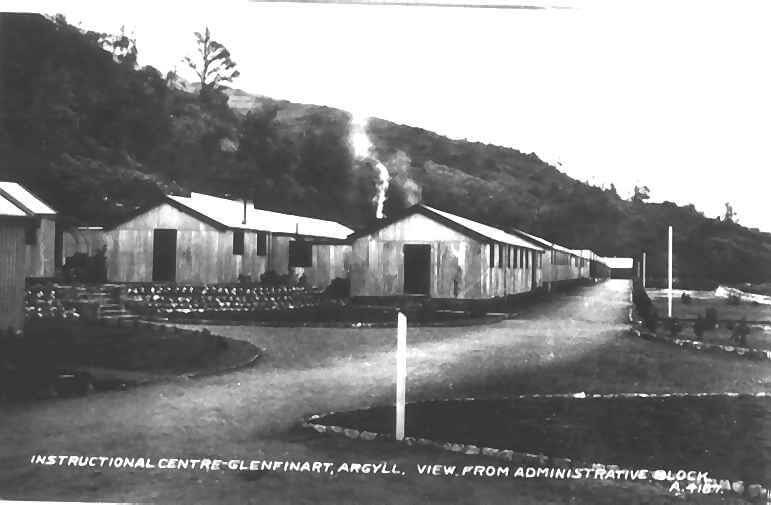

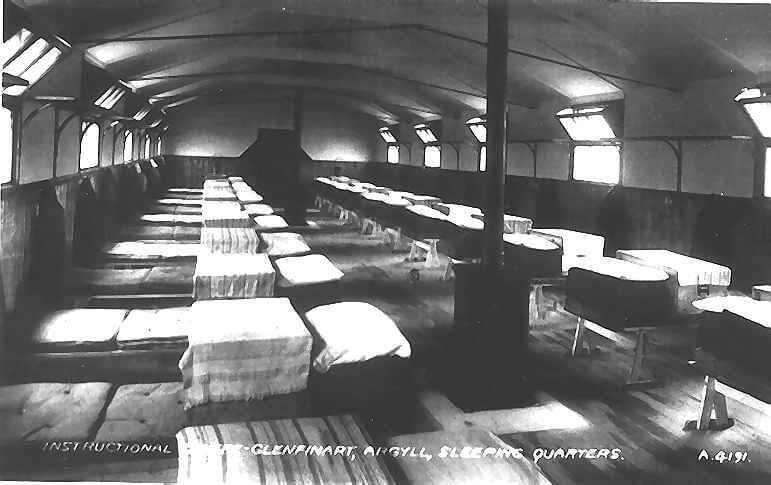

Bureaucratic hurdles and a lack of basic facilities hindered the NOFU immediately, prompting a desperate scramble for alternative accommodations.

By mid 1940, most of the original issues had been resolved, but a new challenge arose when most loggers began to refuse to renew their contracts. Instead, many returned to Newfoundland, and some even enlisted in the British armed forces.

George and Arthur Brewer, two brothers from Epworth, Nfld., for instance, transferred to the Royal Navy before joining the crew of HMS Hood. On May 24, 1941, they were among the 16 Newfoundlanders killed during the Battle of Denmark Strait.

The lumber industry was as dangerous as it was crucial.

In response to the NOFU’s depleted numbers, the British government requested an additional 1,000 men. The first draft of 205 loggers landed on July 14, 1940, with 800 more joining the following month.

Aside from bolstering Britain’s coal industry, which relied heavily on a steady supply of wooden frames to support the mines, the NOFU produced telegraph poles, pulpwood, shipbuilding lumber and materials to repair bomb damage. It also took on defence duties within the Home Guard beginning in 1940.

Two years later, 700 Newfoundlanders formed the 3rd Inverness (Newfoundland) Battalion.

The lumber industry was as dangerous as it was crucial. By the end of the war, at least 34 foresters had died in accidents, and more were severely injured.

Even after the end of hostilities, approximately 1,200 Newfoundlanders stayed in Britain to help the industry adjust to the postwar world. The NOFU wasn’t disbanded until July 1946, at which point most members sailed home.

Having been considered civilians, however, the men were initially denied veteran benefits. Former loggers would fight for their rights in the following decades, even after Newfoundland’s confederation into Canada.

Finally, in 1962, the Canadian government’s Civilian War Allowances Act recognized the unit’s wartime contributions. Nevertheless, only in 2000, more than 60 years after their service, did the aging NOFU members become eligible to receive benefits and pensions.

Advertisement