I Echelon officers of 2nd Battalion, Le Royal 22e Régiment at battalion headquarters, behind Hill 355 in Korea. [Wikimedia]

These were the simple yet assertive instructions of Lieutenant-Colonel Jacques Dextraze, commander of 2nd Battalion, Royal 22e Régiment, as his men prepared for the looming Battle of Hill 355 Nov. 22-25, 1951, amid the Korean War.

By that stage, indeed since that summer, international calls for peace negotiations had persuaded both sides to discuss the prospect of an armistice. It was a notion that seemed almost as distant as Canada itself to the troops settling into their hastily made defences on the saddle between the U.S.-occupied Hill 355 to the east—dubbed “Little Gibraltar”—and the Chinese-held Hill 227 to the west.

Enemy forces had recognized an opportunity to extend their hand at the negotiating table. They intended to eject the U.S. 7th Infantry Regiment from their commanding position. The Van Doos, as the Royal 22e is known, had been sent to bolster the American defence as all signs pointed to a renewed Chinese offensive; intermittent shelling throughout the 22nd all but confirmed it.

Finally, perhaps inevitably, the enemy assault commenced at 3 p.m. on Nov. 23. While the Chinese concentrated efforts on the Americans atop Hill 355, the French Canadians were soon subjected to probing attacks.

It didn’t take long for an unidentified voice to be heard frantically over Dextraze’s wireless. “Collapse! This is collapse. Over.”

Responding, the frustrated commander quipped: “Collapse, sit down, stand up. Do what you want…but for God’s sake, get off my battalion net!”

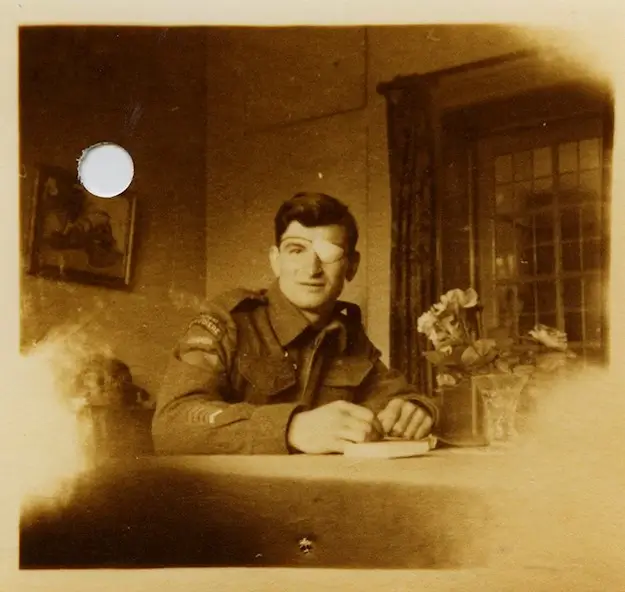

Corporal Léo Majo who earned the Distinguished Conduct Medal for efforts in Korea. [Wikimedia]

”I’m not pulling out. Engage with mortars.”

The Chinese had successfully pushed the 7th Infantry off Little Gibraltar, exposing the Van Doos’ entire right flank. With Hill 227 to the left already in communist hands, the central saddle was at risk of encirclement.

Dextraze, however, remained undeterred.

“We will hold our positions,” he instructed his beleaguered force over the radio. “We will fight to the end.”

For the next few days, the Canadians fought against a tide of Chinese attackers, with most waves charging in with grenades, burp guns and even bayonet-armed sticks. ‘D’ Company, at the front of the regiment’s perimeter, suffered greatly in the onslaught. Nevertheless, they, like the other defenders, obeyed Dextraze’s orders.

Corporal Léo Major was the exception to the rule. Renowned for almost single handedly liberating the Dutch town of Zwolle during the Second World War—a death-defying exploit that earned him the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM)—the Quebecer was now tasked with reclaiming a Canadian position with his small scout and sniper platoon. Successfully completing the mission, but under heavy fire, Major reached out to Dextraze on the wireless.

When Dextraze demanded he withdraw, the resolute corporal relayed a simple but firm response: “I’m not pulling out. Engage with mortars.” An outright refusal of his superior officer’s command.

With friendly rounds falling dangerously close to his men—so much so that the explosions could be heard over the mortar platoon radio phone—Major’s actions, though insubordinate, had the desired effect of checking the Chinese advance.

By the early hours of Nov. 25, the worst was over. With the Van Doos having taken the brunt of the communist assaults, the U.S. 7th Infantry was able to reclaim Hill 355, leaving the enemy no better off than at the battle’s start.

It had come at a cost of 16 Canadian dead and another 44 wounded. The Chinese had paid an even higher price, with at least 742 corpses counted in the saddle area. Accounting for how the communists often removed their fatalities from the field where possible, estimates suggest that upward of 2,000 were killed.

For his efforts, Major received a bar to his DCM, the only Canadian to receive the distinction in different wars. He died on Oct. 12, 2008, at age 87.

Dextraze, meanwhile, was elevated to chief of staff for the UN peacekeeping headquarters in the Congo in 1963-64 and later served as Canada’s defence chief from 1972 until 1977. On May 9, 1993, at the age of 73, he died.

Advertisement