Artist Wilhelm Malchin depicts a German Zeppelin attack in England in June 1915. [Wilhelm Malchin/Wikimedia]

Shortly before midnight on Oct. 1, 1916, Second Lieutenant Wulstan Tempest, soaring through English skies in a B.E.2c biplane, spotted his looming target.

At more than 14,000 feet (4,267 metres), the German Zeppelin Luftschiff 31—or L.31—looked like it rained death from the heavens, however hellish that prospect seemed. But now, of course, it was the 25-year-old pilot’s turn to wreak havoc upon the airship, crewed by 19 and, with its onboard machine guns, far from defenceless.

Tempest remained undeterred. He would be the oncoming storm.

Born in Yorkshire, England, on Jan. 22, 1891, Tempest had previously immigrated to Saskatchewan with his brother, Edmund, where they farmed. The war’s outbreak prompted them to return and enlist in the U.K. in October 1914.

Tempest’s military life began in the infantry, during which time he participated in the Second Battle of Ypres only to suffer from the effects of a gas attack. Invalided home to recuperate, he spent a brief stint performing garrison duties, but was eventually transferred to the Royal Flying Corps, earning his wings in 1916.

By that stage, Britain was no stranger to the Kaiser’s Zeppelin menace.

Preceding the invention of the aeroplane, German Ferdinand von Zeppelin created the first successful airship in 1900, a lighter-than-air, hydrogen-filled flying machine that showed great potential for ferrying passengers across significant distances. It wasn’t long before it was transformed into a fairly capable killing machine, too.

German Ferdinand von Zeppelin created the first successful airship in 1900. It wasn’t long before it was transformed into a fairly capable killing machine, too.

The first Zeppelin air raids of the Great War targeted London and Paris in 1915, when the Allies’ defence capabilities were woefully inadequate. Gradually, the deployment of anti-aircraft guns, searchlights, communications facilities and night fighters—each armed with incendiary ammunition that could transform a German airship into a fiery inferno—helped level the playing field.

Nevertheless, these early stealth bombers-in-all-but-name continued to sow fear among the British people. On moonless nights, Zeppelins could cut their engines and drift silently over their prey below, waiting for the right moment to strike.

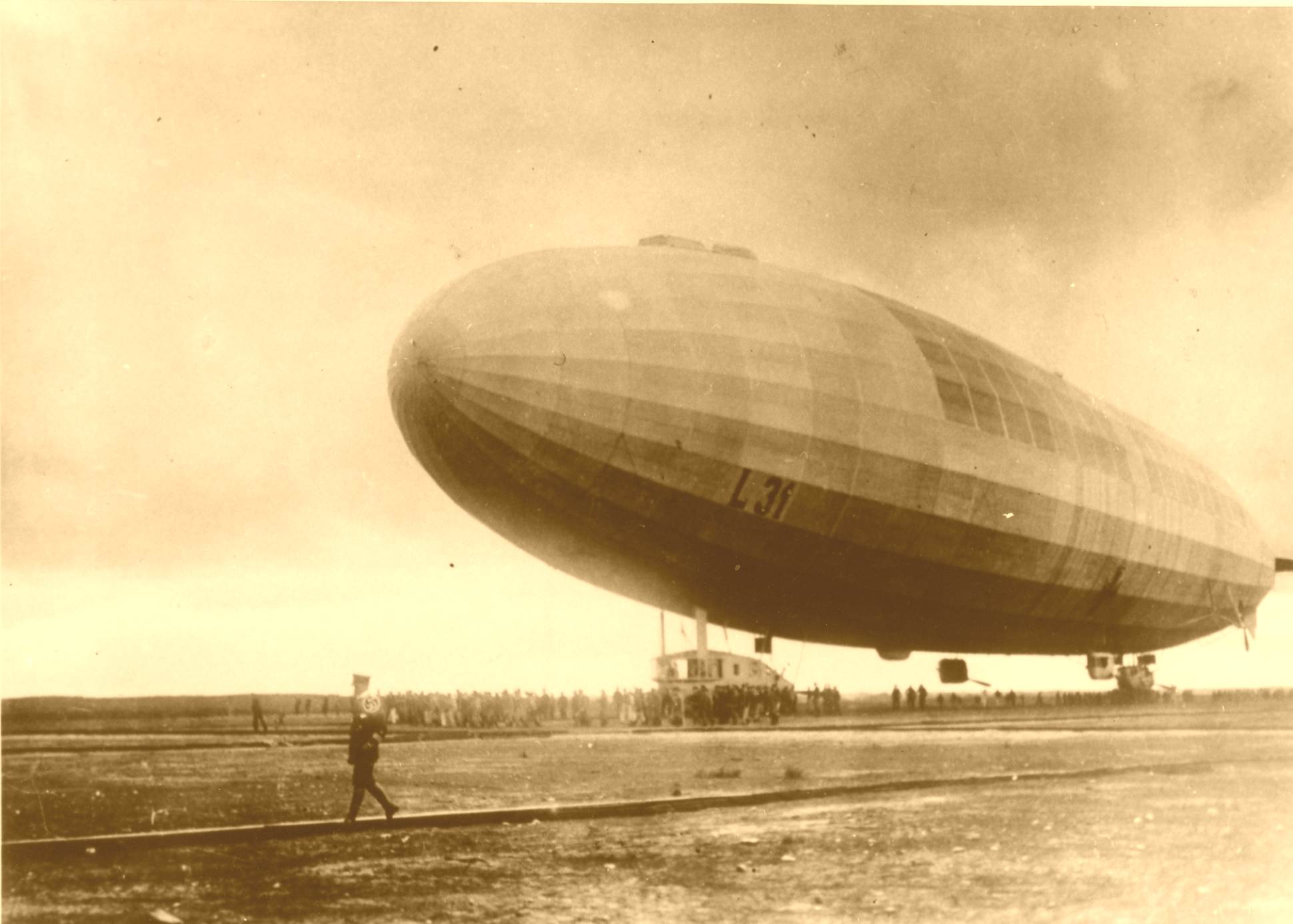

Zeppelin L.31 readies for launch. [Wikimedia]

On Oct. 1, 1916, L.31’s Kapitänleutnant Heinrich Mathy, Germany’s most experienced commander and a renowned ace, tried just that. Unfortunately for the enemy raiders, the ploy failed when London’s searchlights lit the airship like a Christmas tree. Anti-aircraft fire soon filled the sky, adding to the mayhem.

That’s when Tempest delivered the coup de grâce.

Climbing for 20 minutes, the British-Canadian pilot reached the Zeppelin after hand-pumping fuel due to a malfunction aboard his aircraft. Alas, he was too late to prevent L.31 from dropping its bombs, hence why it had climbed to such a high altitude, but Tempest could at least ensure that Mathy’s 15th raid was his last.

Oxygen was scarce, the Zeppelin’s armaments had opened up, and yet Tempest pressed home the attack. Firing his machine gun as he approached and again as he passed underside, his bullets initially caused little damage against the behemoth.

The pilot changed tactics, positioning himself under the airship’s tail and sending incendiaries through its length. “I saw her begin to go red inside like an enormous Chinese lantern,” he recalled. Tempest then launched his B.E.2c into a nosedive, corkscrewing to avoid the blazing wreck as L.31 plummeted toward the Earth.

“I saw her begin to go red inside like an enormous Chinese lantern.” Tempest then launched his B.E.2c into a nosedive, corkscrewing to avoid the blazing wreck.

With no parachutes aboard the stricken airship, its crew faced a horrendous choice: burn or jump to their deaths. Mathy chose the latter, leaving a deep impression in a farmer’s field when his body hit the ground.

This image allegedly shows the imprint made in the ground of Kapitänleutnant Heinrich Mathy, commander of L.31, after he jumped from the burning airship. [alanmalcher.com]

Thousands of people watched the Zeppelin as it crashed at Potters Bar, a community just north of London. There were no survivors aboard L.31.

Not only had Tempest downed an enemy airship, together with its esteemed ace, but his actions undermined confidence at the German high command. Though similar raids continued after Oct. 1, their frequency diminished. By 1917, a total of 77 of 115 Zeppelins had been shot down or completely disabled.

Wulstan Tempest made this trophy by mounting his photograph to fragments of his plane’s propeller and pieces of Zeppelin L.31. It is now in the collection of the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. [CWM/19650080-001]

Despite this, British civilians were still well within the Kaiser’s reach. That same year, the first Gotha bomber raid took place. These giant German aircraft heralded a new era of aerial combat that brought the Great War closer than ever before.

Between May 1917 and May 1918, more than 300,000 people sought shelter in the London underground amid the raids—double that witnessed at the height of the London Blitz in September 1940, according to Britain’s Imperial War Museums.

Regardless of what lay in store, Tempest deserved recognition for his heroic actions. Two weeks later—on Oct. 13, 1916—he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for “conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty,” reads his citation.

Between May 1917 and May 1918, more than 300,000 people sought shelter in the London underground amid the raids.

Nor were his exploits over.

Almost exactly a year later, Tempest earned the Military Cross for bombing enemy railway facilities and aerodromes near the Western Front. “On one occasion,” noted his latest citation, “he descended to a very low altitude and dropped bombs on two moving trains, causing them both to be derailed.”

Tempest—who died in 1966—appeared modest about his death-defying ventures, even immediately after destroying L.31. The next day, he and hordes of fellow sightseers descended upon Potters Bar to glimpse the wreckage. Finding the area cordoned off by the army, Tempest reportedly decided against revealing his identity, which would have likely allowed him free access, and instead paid a shilling so that he could quietly glimpse the result of his efforts.

Advertisement