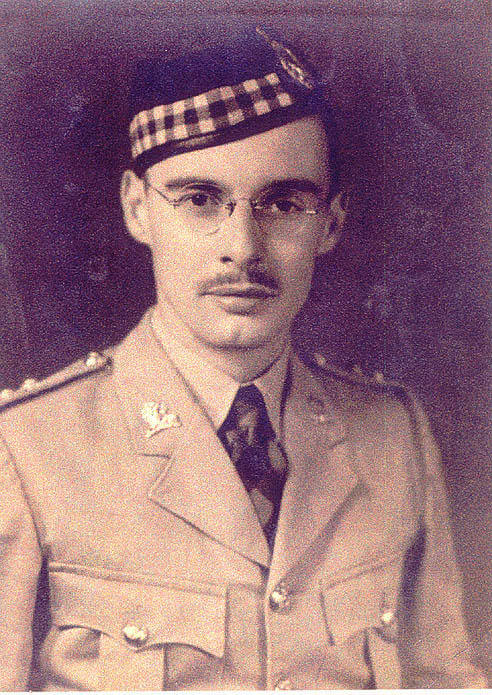

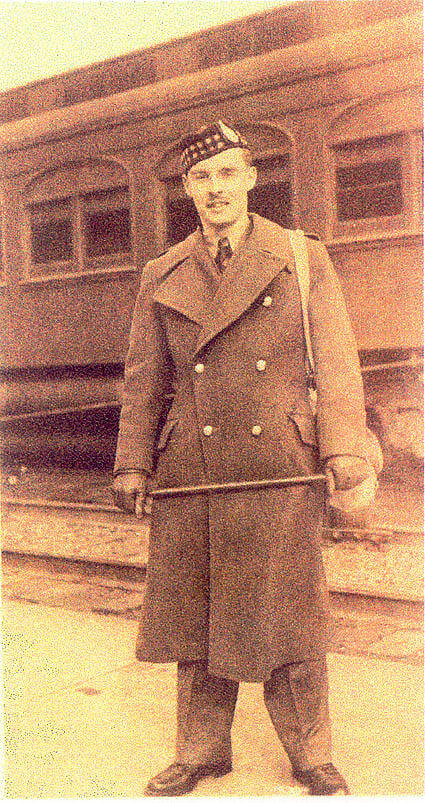

Major Stewart Hastings Bull commanded ‘A’ company of the Essex Scottish Regiment at Caen until he was wounded and lost an eye.

[The Canadian Letters and Images Project]

The regiment had been gutted at Dieppe. Major Bull’s first taste of war came almost two years later during the battle for Caen. A runner summoned him the night he arrived at their encampment in an orchard just outside the city, 15 kilometres from the D-Day beaches. His second-in-command wanted to see him.

So, off they went among the trees. German shells were falling all around. He arrived to find Captain Paul Cropp standing alongside the remains of one of their soldiers.

“I’ve lost a man; he’s had his head blown off,” said Cropp, who would go on months later to earn the Military Cross.

“Well, did you get his dog tag?” Bull asked him.

“I tried, but I can’t. Will you try?”

“All right,” said Bull, a Windsor, Ont.-born teacher who relates the story in a transcript from an audio recording he made when he was 86.

“So, I knelt down and put my hand in, and it was rather awful, because of the severed head,” Bull relates. “I tried to feel around, but I couldn’t find that dog tag.”

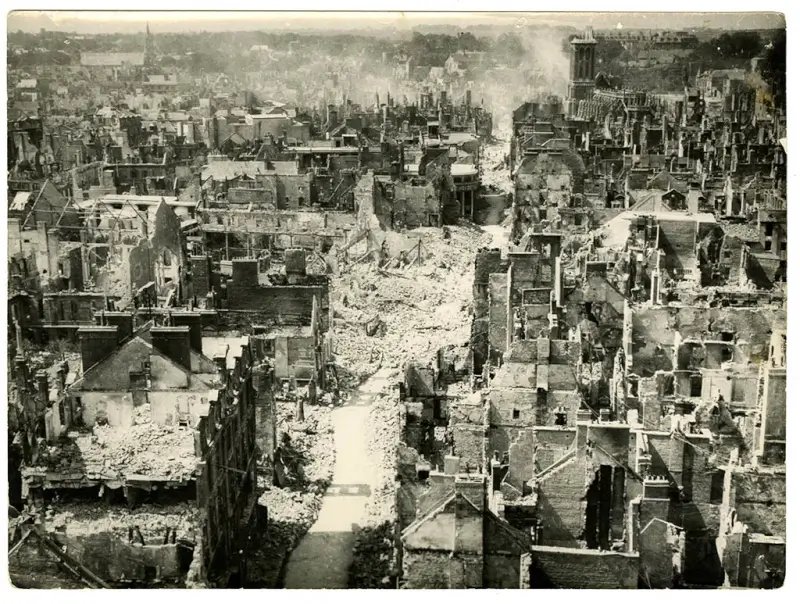

Canadian troops enter Caen, France, on July 10, 1944.

[Harold G. Aikman/LAC/PA116510]

“So, that was my first introduction to war, in the physical sense, and it was pretty bloody,” said Bull. “Well, that night the RAF bombed Caen. It was very close to where we were, but they were accurate.

“They spent a lot of bombs, and demolished the whole city, which had a long history.”

Caen was an important transportation hub, straddling the Orne River and Caen Canal. Already withdrawn to form a perimeter on the edges of the city, the Germans survived the bombing and mounted a mighty defence. It took six weeks of fighting and heavy shelling to capture the Normandy capital, costing the lives of 3,000 civilians and some 30,000 British and Canadian soldiers.

A Handley Page Halifax bomber of No. 4 Group RAF over northern Caen after the bombing of July 6.

[RAF/IWM/CL347]

“They killed a lot of people, and took some prisoners. George Ponsford, our anti-tank officer, tried to fight them off, but his guns weren’t big enough, and he was killed.”

Ponsford, 31, was from St. Thomas, Ont. Lieutenant Jack Chandler, 30, of Springhill, N.S., was the next to die, gunned down as he dug a slit trench.

Captain Herbert Dann, an Irish-born Calgarian and second in command of ‘C’ company, was killed trying to help a corporal and his section who had become isolated from the rest of the regiment.

A few days later, German troops took up positions on a high point overlooking the Essex Scottish. ‘C’ company was dispatched to take them out, with artillery and mortar support.

“The man who was responsible mostly for that was the company sergeant major of ‘C’ company, Les Dixon, who was a regular firebrand,” said Bull. Dixon had earned a Military Medal at Dieppe—and made it out. He would go on to earn two bars to his MM in the next 10 months, the first of them in October at Falaise.

A British soldier carries a little girl through the devastation of Caen on July 10.

[Malindine/No. 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit/IWM/B6781]

Bull was losing too many non-commissioned officers—“a sergeant here, and a corporal there. These were valuable men. There was a German sniper that was picking them off, and I thought, ‘I’ve got to get hold of that.’ So, I called battalion headquarters and I said, ‘send me Phillips and Anderson.’”

Phillips and Anderson were snipers. They arrived in minutes with sniper rifles in hand. “There’s a sonofabitch out there who’s picking off my NCOs,” he told them. “I want you to get him…. Find him and shoot him, get him out of there.”

He promised 10 British pounds (almost C$970 today) to the man who got him.

“My face was covered with blood from my wound and I took out my shell dressing to try and clean it off, but there wasn’t enough.”

The pair went crawling through a wheat field. About an hour later, a hand came up. It was Anderson, with one finger raised. “We got him,” Anderson said after they returned. “He was on a bridge and he was cleaning his rifle, and I nailed him.”

Bull asked them if they would like to have another go, offering 15 pounds this time. They said yes and left for the afternoon. When the day was done, they reported one kill. The shooter was Anderson, again.

“That was that, and we didn’t have any more trouble from snipers.”

The Essex Scottish had been holding their ground for about a month when the order came for the breakout. They were to be the lead infantry element, riding aboard Bren gun carriers behind the lead tanks and advancing to a start line, where they dismounted.

The devastation of Caen in 1944 was monumental.

[Liberation Route Europe]

Despite his wounds, Bull issued detailed orders for his replacement and their next moves, to take out a village at the top of the hill in front of them.

“My face was covered with blood from my wound and I took out my shell dressing to try and clean it off, but there wasn’t enough. So, I got out my haversack and pulled a towel out and wrapped it around my head.

“Just then the colonel, Colonel Jones, opened my door and said, ‘what’s happened? What are you doing? Where are you?’ And I said, ‘I don’t know sir, I’m blind. I can’t see. I’ve gotten Mr. Phoenix to take over.’ And he said, ‘Well, I need your vehicle.’

“So, he grabbed hold of my shoulders and he pulled me out onto the ground, and he laid me there and he said, ‘take care; I’ll send somebody for you as soon as possible.’ And he got in the vehicle and drove away.”

Up ahead, the tanks leading their column were being decimated by German artillery and tank fire. Some of the tankers panicked and drove back through the Canadian lines, running over their own soldiers.

“They had been crushed in the mud,” said Bull. “However, they were still alive.

“But I couldn’t do anything; I was lying on the ground. It was quiet, as if the battle had departed from me. So, I called, ‘stretcher-bearers! stretcher-bearers!’ And a voice from somebody said, ‘it’s all right sir, they’re coming.’”

Bull went on to teach high school history and English at University of Toronto Schools. He died in 2003 at age 86.

[The Canadian Letters and Images Project]

“The next thing I knew, I was in a hospital tent. This was the first Canadian hospital in the field, which had been set up just after we’d captured Caen. And somebody—I couldn’t see anything of course—somebody said to me, ‘do you know Dr. Brian of Windsor?’ I said, ‘yes.’ And he said, ‘he wants to talk to you.’”

The doc didn’t pull any punches. “Well, Stew Bull,” he said, “you’ve had a rough go. You’ve lost your right eye, and there are some other things that are wrong, but I’ve patched you up all I could, and I’m sending you back to England. We’ll take you to Bramshott, or Basingstoke hospital where they can do a better job.”

Bull was flown out with a wounded airman and ended up in the Canadian hospital at Basingstoke, home to the army’s elite plastic surgery team. He was there for three months.

Dr. Hoyle Campbell, who in 1956 established the Institute of Traumatic, Plastic and Restorative Surgery in Toronto, cut a piece out of Bull’s cheek and replaced missing parts of his nose. “Now you have half a nose and half a cheek,” Campbell told him. “They’ll heal up. Take it easy. And I’m going to send you back to Canada.”

And that was Stewart Bull’s war.

The Essex Scottish would help take Caen, fought to help close the Falaise gap and, on Sept. 3, 1944, entered Dieppe as celebrated heroes. They paused at the graves of their fallen brethren from 1942, took part in a divisional march past, and toured the killing grounds.

One of Canada’s oldest infantry regiments dating to 1749, they would fight through Belgium, the Netherlands and into Germany. The 1st Battalion would earn 18 Second World War battle honours and emerge with the highest number of casualties of any unit in the Canadian Army: 553 killed and about 2,000 wounded.

Bull went on to teach high school history and English at University of Toronto Schools and became regimental historian, museum curator and council member for The Queen’s York Rangers. Stewart Hastings Bull died in 2003 at age 86.

“He will be remembered first and foremost as a lively and inspiring teacher,” said his obituary. “He encouraged generations of students, and dedicated boundless energy to school spirit, cadets, debating and dramatics.

“Stewart was a steady leader who shared his love of people, creative spirit, and enthusiasm for life with all he knew.”

Advertisement