James Prinsep Beadle’s painting “Piper James Richardson, VC, Canadian Scottish, Regina Trench, 8.10.1916” hangs in the officers’ mess of the Royal Scots Regiment in Edinburgh. Lance Corporal Richardson is one of four members of the 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish Regiment) awarded the Victoria Cross during WWI.

[Bagpipe News]

The 16th Battalion (Canadian Scottish Regiment) was crossing more than 600 metres of no man’s land to their objective in the pre-dawn hour, advancing in “long, snake-like lines…by the light of the bursting shells,” as one officer described it, when they were stopped dead in their tracks.

“On coming in sight of the wire I ran on ahead and was astonished to see it was not cut,” recalled Sergeant-Major Arden Mackie, situated front and centre of the battalion attack. “I tried to locate a way through but could find no opening.

“When the company came up the enemy started throwing bombs and opened rifle fire.”

Richardson moved with his family to British Columbia from Scotland. He enlisted at age 18, just 13 days after Canada went to war with Germany. He was killed at the Somme in October 1916.

[GoC]

“Piper Jimmy Richardson came over to me at this moment and asked if he could help, but I told him our company commander was gone,” said the Scotland-born Mackie. “Things looked very bad and then it was that the piper asked if he would play his pipes—’Vull I gie them wund (wind)?’ was what he said.

“I told him to go ahead and as soon as he got them going I got what men I could together, we got through the wire and started cleaning up the trench.”

A piper of the 7th Battalion (Seaforth Highlanders), leads men of the 26th Brigade down a sunken road after the attack on Longueval during the Battle of the Somme.

[IWM/Q 4012]

Non-Scots, he wrote, might at some point have had a hard time envisioning the value of bagpipes in war, but “their minds were changed after they witnessed the power of the bagpipes to motivate and inspire soldiers on the battlefield.”

The English tried to ban virtually every element of Scottish culture, including the bagpipes, after defeating Scotland’s Bonnie Prince Charlie at Culloden in 1746.

At his treason trial—one of many that took place after the battle—defendant John Reid claimed that, as a piper, he was a non-combatant and therefore not guilty. His English judge ruled, however, that since no Highland regiment ever marched without a piper, the pipes were an instrument of war.

He concluded that Reid had borne arms against the king and should be “hanged by the neck until he was dead.”

It was in the aftermath of this very battle, and such harsh judgements, that tens of thousands of uprooted Scots first brought themselves, and their culture, to what is now eastern Canada. Back in Scotland, loyal Highland regiments were quelling the rebellion.

“The Battle of Achi Baba 1915” by Chris Collingwood depicts a pipe major of the Royal Regiment of Scotland leading Highland troops during the Gallipoli Campaign.

[Chris Collingwood Historic Art]

Some Highland officers were offered land in Canada at the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763. And during the American Revolution of 1775-1783, London issued orders to raise a Scottish regiment in Canada, the Royal Highland Emigrants.

Detachments were garrisoned at Quebec; Saint John, N.B.; Annapolis, N.S.; and Halifax, where Scottish heather has grown freely since Highland soldiers shook its seeds out of their bedrolls in what has since became Point Pleasant Park.

The pipes were integral to them all.

“It was this centuries-old tradition instilled in the descendants of those early Scottish settlers, combined with a sense of duty to country, that drove Scottish-Canadians to enlist when the call went out for men at the start of the First World War in 1914,” wrote Stewart.

“Pipers were once again summoned to their old proud post of duty and honour on the battle front.”

He was just five-foot-eight, 137 pounds, but evidently had mighty lungs.

The point at which Private James (Jimmy) Cleland Richardson, a 21-year-old native of Bellshill, Scotland, began to play was “desperately critical,” says the battalion history. Major Lynch had told him to stay silent until he ordered him otherwise.

“Not a 16th man had got over the wire,” says the account, published in 1932. “The two waves had now merged.

“From the outside of the entanglements some of the men were bombing the German trench; others were trying to force a passage by beating down the wooden stakes, on which the wire was supported, with the butts of their rifles and trampling the wire under foot.”

Rifle fire from the opposing trench was “deadly accurate. It seemed as if the attacking troops to a man would become casualties.”

It was at this moment that Richardson—who had quit his job as an 18-year-old driller to enlist just 13 days after Canada went to war with Germany—began to play, marching fully exposed up and down the length of the wire for 10 minutes.

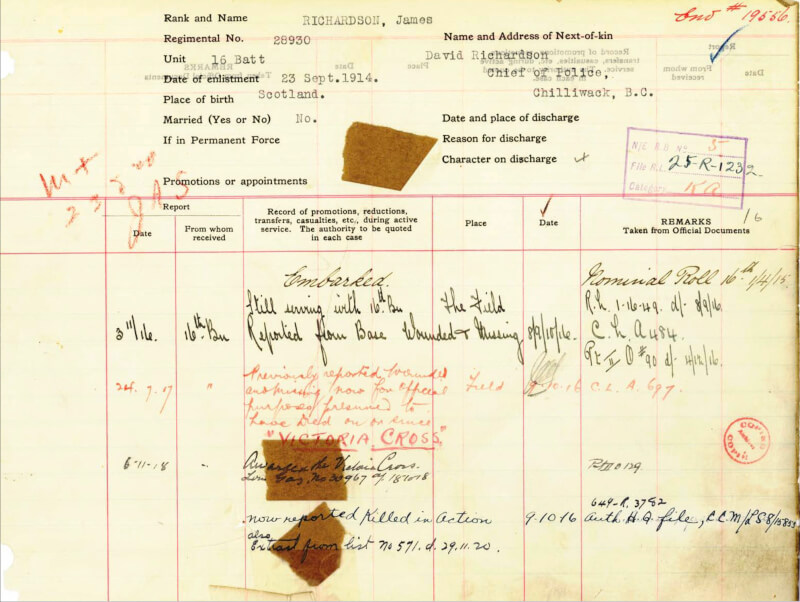

Richardson’s service record catalogues his disappearance and subsequent Victoria Cross.

[LAC]

“He was not originally detailed for the attack. He asked to be paraded before the Commanding Officer; and there pleaded so earnestly to be allowed to go into action that Colonel [Robert] Leckie finally granted him his wish.”

Richardson would be awarded a Victoria Cross for his actions that day—posthumously. His VC citation, published two years later in The London Gazette, said the company was already demoralized in the face of heavy casualties.

“Realizing the situation, Piper Richardson strode up and down outside the wire playing his pipes with the greatest coolness,” it said. “The effect was instantaneous. Inspired by his splendid example, the company rushed the wire with such fury and determination that the obstacle was overcome and the position captured.”

Richardson’s pipes were thought lost for 86 years until they were discovered at a school in Scotland.

[B.C. Legislature]

“After proceeding about 200 yards Piper Richardson remembered that he had left his pipes behind. Although strongly urged not to do so, he insisted on returning to recover his pipes. He has never been seen since.”

He was one of two 16th Battalion pipers, along with Corporal John Park, to die that day. Richardson’s remains weren’t found until 1920. He was buried at Adanac (Canada spelled backwards) Military Cemetery northeast of Albert, France.

His bagpipes were believed lost in the Somme mud for 86 years until 2002, when the pipe major of The Canadian Scottish Regiment (Princess Mary’s) discovered that Ardvreck School in Crieff, Scotland, had a set of bagpipes with the distinctive red, green and gold Lennox tartan used by the pipers of Richardson’s 16th Battalion.

As it turned out, a British army chaplain, Major Edward Yeld Bate, had found the pipes in 1917 and brought them home to the school where he taught. For decades, they served as a broken, stained and mud-caked reminder of an unknown piper from the Great War.

Richardson lies in Adanac Military Cemetery northeast of Albert, France.

[GoC]

Richardson and his family had taken up residence in Chilliwack before the war. His father David was a local police chief, and Richardson had become a regular bagpipes competitor on the B.C. Highland games circuit, appearing in Vancouver, North Vancouver and Victoria. At the time his son was killed in action, Richardson’s father had three of his gold medals for piping.

Richardson wasn’t the first, nor would he be the last of the 16th Battalion pipers to stand out and inspire their troops on the battlefield.

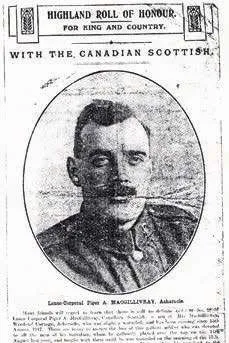

Lance Corporal Alex MacGillivray piped the 16th into battle at Hill 70 in northern France on Aug. 16, 1917.

[ GoC]

During the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915, 16th Battalion pipers James Thompson and William McIvor were severely wounded while playing the troops forward after the German gas attack at Saint Julien. Both later died.

Less than a month after, during a daring daylight assault at Festubert, pipers George Birnie and Angus Morrison stood atop the ruins of a farmhouse and played as the 16th advanced into a hail of machine-gun fire. Both were hit.

“As they fell, the sound from their drones trailed off and the sounds of battle were everywhere once more,” Stewart wrote.

At the Second Battle of Arras in September 1918, Pipe Major James Groat led troops over the top and through barbed wire under heavy machine-gun fire and amid hand-to-hand combat until he was wounded by shrapnel.

It had been his fifth time leading the battalion into battle, and he ended the war with a Distinguished Conduct Medal and two Military Medals among his decorations.

“Groat was the soul of our pipers,” said his commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Cyrus Peck, “full of zeal for the music; a grim, dark-visaged, silent man with a brave heart.”

The battalion history relates the stirring tale of Lance Corporal Alex MacGillivray, who piped his way into legend at Hill 70 in northern France on Aug. 16, 1917.

As the 16th prepared to go over the top against deeply entrenched, heavily defended German troops on the infamous rise north of Lens, the transplanted Scot told his company sergeant-major that he felt “anxious.”

He said he feared that, burdened as he was with his pipes and equipment, the company men might get out ahead of him and “bring disgrace on a Highland piper.”

“Well, if you think that way,” his NCO told him, “ask the company commander to allow you to climb out before us.”

Aerial view of the battlefield at Hill 70 north of Lens, France.

[IWM]

At the so-called “Blue Line,” where the brigade attack was reforming under fire before resuming its advance, MacGillivray continued to play up and down before the companies of the 16th. He then headed off in front of the neighbouring 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada), where he made a “profound impression.”

“Just at this time,” says an account, “when all ranks were feeling the strain of remaining inactive under galling fire, and when the casualties had mounted to over 100, a skirl of the bagpipes was heard, and along the 13th front came a piper of the 16th Canadian Scottish.

“This inspired individual, eyes blazing with excitement, and kilt proudly swinging to his measured tread, made his way along the line, piping as only a true Highlander can when men are dying, or facing death, all around him.

“Shell fire seemed to increase as the piper progressed and more than once it appeared that he was down, but the god of brave men was with him in that hour, and he disappeared, unharmed, to the flank whence he had come.”

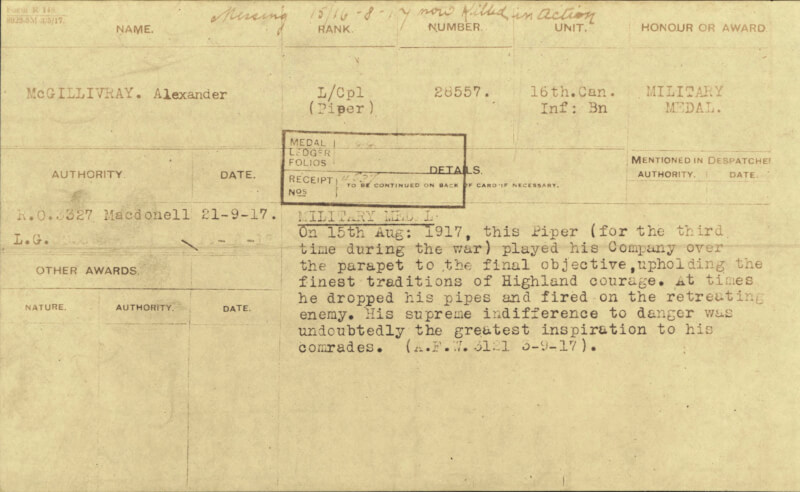

MacGillvray’s Military Medal citation notes his disappearance and subsequent declaration of death.

[LAC]

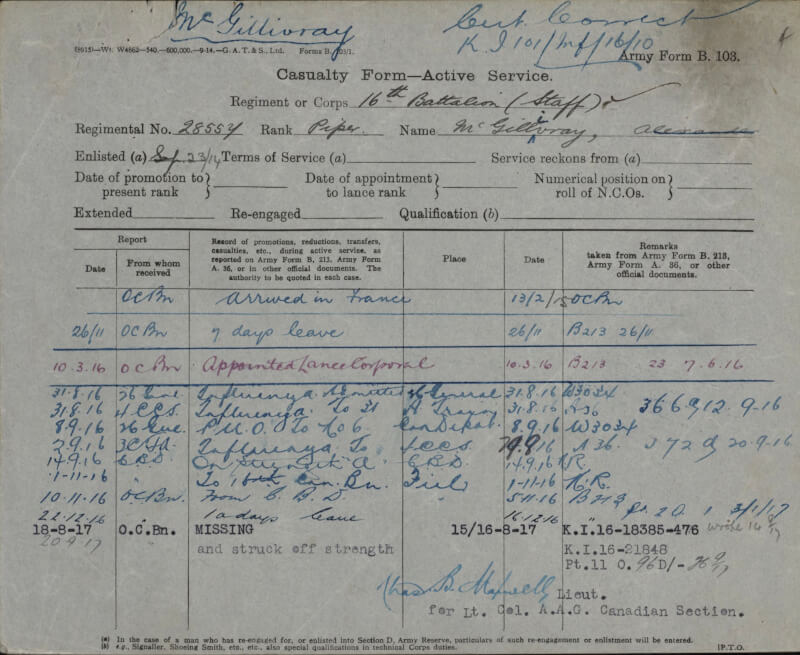

He was reluctant to return to battalion headquarters as ordered until his sergeant-major promised he personally would look for the pipes, with their blackwood drones and ivory accoutrements, and take charge of them.

“The sergeant-major found the pipes next morning about forty to fifty yards in front of the final objective,” says the battalion history. “He brought them back with him, but Alec McGillivray was not there to claim his beloved instrument.

“He was seen to start from the front line on his return journey and then disappeared entirely from view, probably blown to pieces by a shell.”

MacGillivray was posthumously awarded the Military Medal for “acts of gallantry and devotion to duty under fire.”His citation said he played his company over the parapet to the final objective, “upholding the finest traditions of Highland courage.”

“His supreme indifference to danger was undoubtedly the greatest inspiration to his comrades.”

MacGillivray’s remains were never identified. His name appears on the Canadian National Vimy Memorial alongside those of 11,284 other Canadian First World War soldiers killed in France whose ultimate resting place is unknown.

MacGillvray’s service record indicates he’d just come off a bout of influenza when he rejoined his unit at Hill 70.

[LAC]

Stewart reports that more than 50 other Canadian battalions, from every province but Prince Edward Island, maintained pipers and drummers—and not all of them were Highlanders.

Pipers could be found in non-Highland units such as the 107th (Canadian Pioneer) Battalion; the 1st and 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles; the 224th (Canadian Forestry) Battalion; the 3rd, 5th and 6th Canadian Railway Troops; Toronto’s 208th (Canadian Irish) Battalion; and the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, which advanced with nine pipers at Vimy Ridge.

Two pipers from the 25th Battalion (Nova Scotia Rifles), William Brand and Walter Tefler, were awarded Military Medals for playing their companies into battle at Vimy. Tefler lost his leg in the April 1917 fighting.

Advertisement