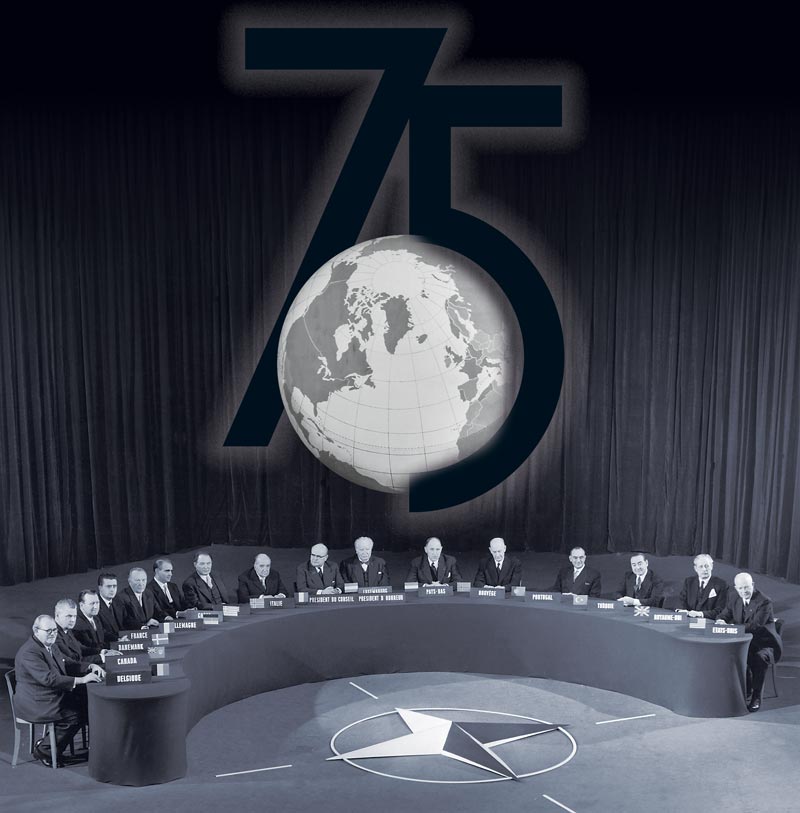

Tensions between the USSR and its western Allies after the Second World War helped lead to the creation of NATO. Its representatives, including Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, gather for a conference in Paris in December 1957. [Keystone-France/Getty Images/106500106]

In the aftermath of the Second World War, much of Europe lay in ruins. In stark contrast to the vibrant Europe of today, the burnt-out shells of several cities and towns dotted the continent. The conflict’s death toll was staggering—approximately 19 million civilians and 17.5 million military personnel.

Rationing, refugee camps and malnutrition were daily facts of life. The mere act of survival was a struggle.

In the summer of 1940, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the USSR, absorbed the three formerly independent Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. They also took over part of Romania and established it as the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. By the time the war ended, Soviet troops had occupied several eastern and central European countries, including the eastern part of Germany.

At the time, the challenge of what to do about a defeated Germany loomed large on the Allies’ agenda. Germany had been divided into four occupation zones, with British, French and American sectors in the west making up two-thirds of the country and a Soviet one in the east comprising the other third. The former capital of Berlin, although deep inside the Soviet-controlled zone, was similarly divided into four parts.

Of course, the Allies had competing philosophies and the main difference centred on reparations. While all Allies had initially agreed on penalties, the Soviets took them to an extreme. They completely dismantled some German factories and moved them to the USSR and confiscated the production of those left behind.

Soviet soldiers in Berlin in 1945. [Shawshots/Alamy/MHC65J]

Additionally, the Soviets were to supply food from their largely agricultural eastern zone to the rest of Germany, in return for a share of the reparations from the western zones. They never did. Forced to feed Germans in their sectors from their own economies, the western Allies reversed their views and now supported the re-establishment of German industry to allow the Germans to feed themselves. The Soviets opposed this move.

When the western powers would not let the USSR claim any more reparations from their zones, co-operation went downhill rapidly. The administration of the zones began to diverge. On Jan. 1, 1947, Britain and the U.S. unified their zones into a new territory called Bizonia, which further exacerbated East-West tensions.

Then in March and April, the foreign ministers of the four occupying powers failed to reach agreement on peace treaties with Germany and Austria. At the same time as the meeting, the Truman Doctrine, which declared that the U.S. would provide support to all democracies threatened by authoritarian entities, further alienated the Soviets.

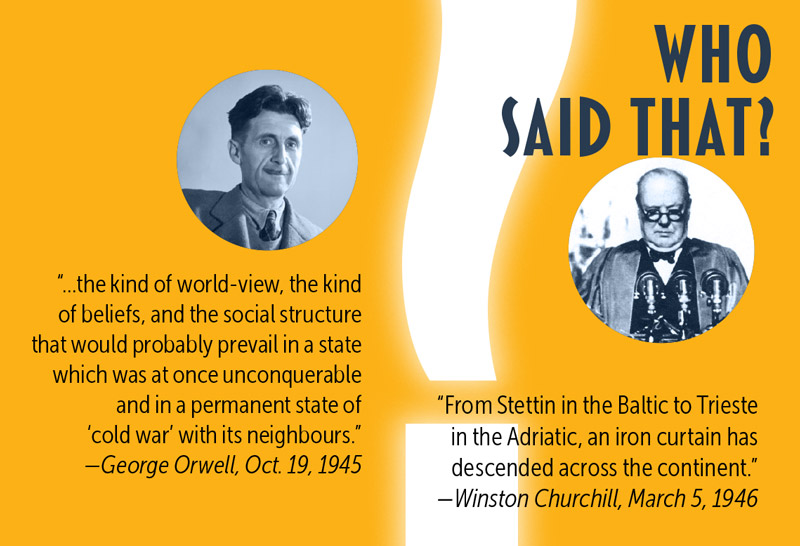

The strategic East-West alliance of the Second World War that had defeated fascism was irretrievably broken in the face of growing postwar hostilities. The Cold War had begun in earnest; the Iron Curtain was a reality.

[Wikimedia; Chronicle/Alamy/2M3R9HG]

The strategic East-West alliance of the Second World War that had defeated fascism was irretrievably broken in the face of growing postwar hostilities.

Boys in West Berlin wave to a U.S. plane delivering food to the Soviet-blockaded territory in early 1948.[dpa picture alliance/Alamy/D3B759]

Meanwhile, the western Allies commenced planning for a new Germany consisting of their occupation zones. When the Soviets learned of these plans in March 1948, they withdrew from the Allied Control Council, which had been established to co-ordinate occupation policy between zones.

In June, without informing the Soviets in advance, British and American officials brought in a new currency for Bizonia and West Berlin. In retaliation, the Soviets issued their own as well. In the face of Soviet hostility, the western Allies feared their occupation zones in Berlin would be subsumed into Soviet-controlled East Germany.

During the war, the city had been pounded by Allied bombing raids, reducing it to rubble. Starvation loomed and adequate shelter was sparse. The black market overshadowed the economic life of the city.

Allied fears were justified. On June 24, Soviet forces began a blockade of all rail, road and canal links to West Berlin. The first crisis of the Cold War had just erupted. In response, Britain and the U.S. initiated an airlift of food and fuel to West Berlin from Allied airbases in western Germany.

The blockade triggered the Treaty of Brussels, signed by representatives from the U.K., France, Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg on March 17, 1948.[Netherlands Nationaal Archief/Wikimedia]

The response to the Berlin blockade showed the USSR that the Allies could supply the beleaguered city by air indefinitely. On May 11, 1949, the Soviets lifted the blockade.

Meanwhile, between 1946 and 1948 and concurrent with these provocations, the USSR had supported Communists across Europe, who threatened democratically elected governments. The result was the establishment of hardline Communist states based on the Soviet system of government in Poland, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Albania.

In many ways, the Berlin blockade was the final straw for some European countries. On March 17, 1948, the U.K., France, Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg signed the Treaty of Brussels, an alliance established in response to an American request for greater European co-operation. Its defence arm was headquartered in the Château de Fontainebleau south of Paris and was headed by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery.

Coupled with the growing tensions between the USSR and the West, fear of further Communist expansion, the need for collective security against the Soviets, the Berlin blockade and the Treaty of Brussels, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, NATO, was created on April 4, 1949. Canada, the U.S., the U.K., France, Belgium, Netherlands, Luxembourg, Denmark, Norway, Iceland, Italy and Portugal were the original signatories to the North Atlantic Treaty, signed in Washington, D.C.

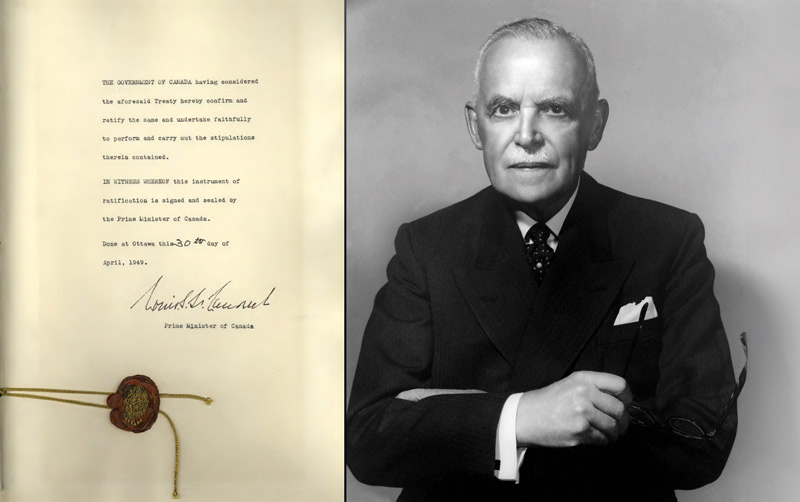

The North Atlantic Treaty, which was signed by Prime Minister Louis St-Laurent on behalf of Canada on April 30, 1949.[NATO; LAC/C-00071]

NATO has been, and continues to be, one of the most effective mutual defence treaties in history. Yet opposition to the threat presented by the USSR was only one of the three pillars that led to its creation. Beyond discouraging Soviet dominance, NATO was also conceived to prevent a renewal of nationalist militarism in Europe and support European political integration.

The central tenet of NATO is contained in Article 5 of the treaty: “an armed attack against one or more…shall be considered as an attack against them all” and each member state will assist those attacked by taking “such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force.”

The NATO agreement established the organization’s oldest body: the North Atlantic Council. The council is the main decision-making group, and its policies reflect the collective will of all NATO members.

Four months after its creation, the alliance established a military committee to provide defence advice to the council. The committee is NATO’s senior military authority and gives direction to its strategic commanders.

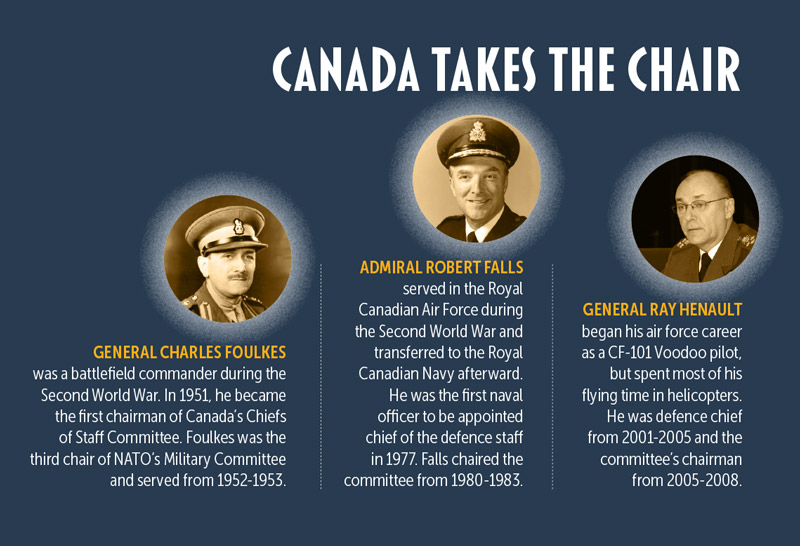

The chair of the committee is elected from among the NATO member chiefs of defence. The term of office was originally for a year, but since 1958 has generally been two to three years.

All the original signatories (except Iceland and Luxembourg), plus some of the later members, have provided the chair of the committee. Canada filled the chair three times.

[LM archives (2); NATO/Wikimedia]

U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, then NATO’s supreme commander, unveils the organization’s first flag in October 1951.[U.S. Army/Wikimedia]

Initially, NATO did not have an integrated command structure that could co-ordinate its actions. This changed dramatically with the detonation of the atomic bomb by the USSR on Aug. 29, 1949, and the invasion of South Korea by North Korea on June 25, 1950.

NATO quickly established a consolidated command structure. Known as Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe, it built new facilities near Versailles after four months in Paris.

U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower became the first supreme allied commander Europe in December 1950. The position has always been held by an American, who is also commander of the U.S. European Command.

In February 1952, NATO created a permanent civilian secretariat in Paris. Its first secretary general was former British general Lord Hastings Ismay, who had been Churchill’s primary wartime adviser. Ismay is famously credited with saying NATO was created “to keep the Soviet Union out, the Americans in, and the Germans down.”

The secretary general chairs the council. Secretaries general have come from a number of countries, but have always been European.

As the first major conflict of the Cold War, the Korean War caused NATO countries to significantly increase their armed forces. Additionally, all members except Iceland (which has no armed forces) and Portugal, including soon-to-join Greece and Turkey, provided resources. Canada was the third largest contributor of troops after the U.S. and the U.K.

As the first major conflict of the Cold War, the Korean War caused NATO countries to significantly increase their armed forces.

Canadian Armed Forces and NATO

The Cold Warand fear of possible Soviet aggression resulted in Canada increasing its defence budget significantly and stationing troops in Europe. Beginning in 1951, Canada’s commitment eventually grew to a powerful mechanized brigade group stationed in West Germany and an air division of four modern fighter wings in France and West Germany.

Additionally, Canada committed infantry battalion groups to Allied Command Europe Mobile Force. These troops were stationed in Canada, but could quickly deploy to Europe if necessary.

Canada’s stationed commitments in Europe were halved starting in 1967 and co-located in the Black Forest area of West Germany. When some NATO allies criticized this decision, the government formed the Canadian Air-Sea Transportable Brigade Group in 1968. The group was stationed in Canada, but could theoretically deploy to Norway on 30-days’ notice during times of tension.

The commitment ended in 1987, and formally closed in 1993 with the end of the Cold War and the return of army and air force units to Canada.

Although not stationed in Europe, between 1955 and 1964 the Royal Canadian Navy received 20 world-class destroyer escorts. Known as the “Cadillacs,” these Canadian-built, anti-submarine warfare vessels could handle the harsh conditions of the North Atlantic.

In 1970, RCN ships began to serve tours in NATO’s Standing Naval Force Atlantic, an integrated flotilla to provide the alliance with an immediate reaction naval force for emergencies. In 2005, this group was renamed Standing NATO Maritime Group 1.

At the same time, the Standing Naval Force Mediterranean was renamed Standing NATO Maritime Group 2 and began to include RCN ships. Canadian officers have commanded both forces.

The Wall

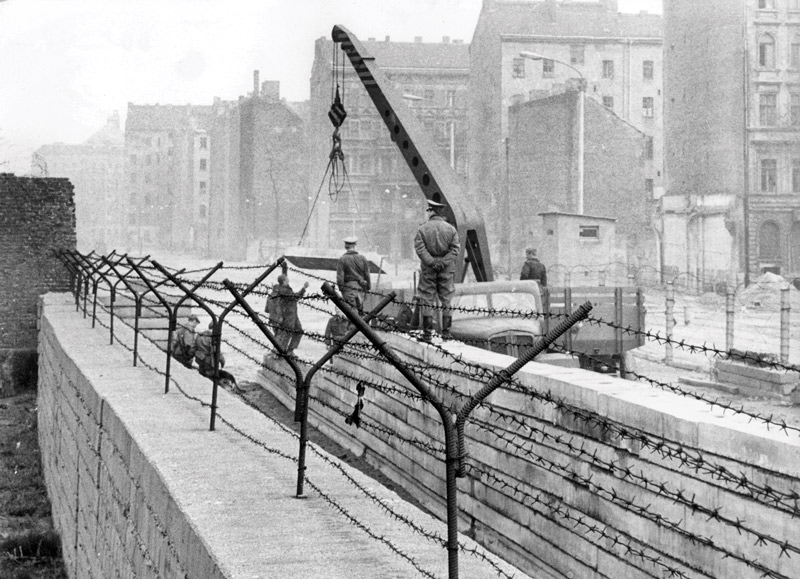

The Berlin Wall was one of the most iconic symbols of the Cold War. The barrier physically—and ideologically—divided Berlin from 1961 to 1989. Constructed by East Germany, the Wall cut off West Berlin from East Germany and East Berlin.

The barrier consisted of guard towers along 3.6-metre-high concrete walls topped with barbed wire, accompanied by a wide “death strip” containing anti-vehicle trenches, strips of nails and other defences.

Before the Wall, about 2.5 million East Germans had fled to West Germany, which threatened to destroy their country’s economy. In response, East Germany built the Wall to close off its citizens’ access to the West.

The Wall prevented almost all such movement. More than 100,000 people tried to escape over it; some 5,000 succeeded. At least 191 people were killed attempting to circumvent it.

The Wall “fell” in November 1989, part of the astonishingly rapid demise of Communist governments in Eastern Europe and the reunification of Germany.

Workers build a second barrier as part of the Berlin Wall in 1967. [dpa picture alliance/Alamy/E8FDE6]

Thousands of East Berliners cross to West Berlin after the Wall was breached in November 1989. [Independent/Alamy/2F9KN40]

In 1952, Greece and Turkey were admitted to NATO, followed by West Germany in 1955 and Spain in 1982. The admittance of West Germany coincided with the creation of a rival NATO regional alliance. The Warsaw Pact consisted of the USSR and its satellite states of East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania and Albania (which withdrew in 1968).

Although theoretically based on collective decision making, in practice the Soviets dominated the pact and made most of its decisions. The treaty also professed non-interference in the domestic affairs of member states, yet the USSR used it to justify its suppression of popular dissent in Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968 and Poland in 1981.

In February 1966, French President Charles de Gaulle announced that France would withdraw from NATO’s integrated military structure while remaining a member of the alliance. This entailed moving all NATO forces from France, including Royal Canadian Air Force units. It also meant a move to Belgium: NATO headquarters to Brussels and supreme headquarters to Casteau, near Mons.

NATO transformed with the danger, moving from an exclusively defensive alliance to a proactive one.

NATO was successful throughout the Cold War in deterring military aggression and its collective forces were not involved in any military engagements. But the end of the Cold War changed the old order and new threats emerged alongside long-standing ones.

NATO transformed with the danger, moving from an exclusively defensive alliance to a proactive one. Between 1990 and 1992, before its first major crisis response operation in the Balkans, the alliance conducted several minor military operations, mostly involving increased airborne warning and control system flights.

The fall of the Soviet Union and the Communist-dominated states of Eastern Europe led the constituent nations of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia to declare their independence. This began in June 1991 with Slovenia and Croatia, followed by Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia.

After the breakup of Yugoslavia, the UN, NATO and the European Union provided peacekeepers. The first NATO commitment was Operation Joint Endeavour in December 1995 with the 60,000-strong Implementation Force. Its aim was to enforce the Dayton Accords, which ended the war in Bosnia.

Concurrently, NATO operated a maritime blockade of the region and enforced a no-fly zone.

The Implementation Force ended its work in December 1996 and was immediately replaced by the NATO Stabilization Force. It consisted of about 12,000 troops who were to assist Bosnia and Herzegovina in becoming a democratic country. The force was steadily reduced in size and the mission was handed over to the European Union in late 2004.

Meanwhile, NATO also enforced a no-fly zone over Bosnia and Herzegovina starting in October 1998. When its warnings were ignored, the alliance launched a 78-day bombing campaign to force Serbia to stop its attacks against Kosovo.

In March 1999, NATO established a security force in Kosovo. It was successful and is steadily reducing in size until the country’s own units can take over.

In August 2001, NATO launched a month-long initiative to collect weapons from the ethnic Albanian minority in Macedonia, who had been attacking government forces.

Canada contributed to all NATO missions in the Balkans. Some 40,000 Canadians served there for either NATO, the UN or the European Union.

To date, NATO’s Article 5 has been invoked only once. Less than 24 hours after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in the U.S. that killed almost 3,000 people, NATO invoked the clause as an act of solidarity with the Americans.

U.S. forces immediately commenced operations in Afghanistan when the ruling Taliban refused to hand over Osama bin Ladin, the attack’s mastermind. This was followed by the commitment of military resources by several NATO and non-NATO countries to the subsequent war.

Starting in August 2003, NATO led the UN-mandated International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan. Its mission was to create conditions for the Afghan government to exercise its authority throughout the country and increase its security forces’ capacity.

That operation ended in December 2014 and the next month the alliance commenced training Afghan security forces to fight terrorism and maintain security in the country. That concluded in September 2021 when NATO suspended all support to Afghanistan.

Canada contributed military resources to NATO missions in Afghanistan from the beginning. The country’s combat role ended, however, in 2011, and the last Canadians left in March 2014 (see “Canada’s longest war” on page 18). More than 40,000 Canadian Armed Forces personnel served in Afghanistan.

Today, threats posed by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, China’s regional expansionism along with terrorism, climate change, regional instability, technological advances and cyber security are among the major challenges for NATO. The alliance, however, has been successful in realizing its aim of collective security for the last 75 years. As such, its shared approach remains the best bet for western countries to overcome any potential problems of the future.

Advertisement