The SS Green Hill Park burns after an explosion on March 6, 1945.[Don Coltman/City of Vancouver Archives/CVA 586-3572]

Just before noon on March 6, 1945, 16-year-old Ordinary Seaman George Conway-Brown entered the mess of SS Green Hill Park. Having completed his work replacing emergency rations and equipment in the vessel’s lifeboats and rafts, he settled down beside fellow crew members for a soup lunch.

The 10,000-ton Victory-class merchant ship—constructed by the Burrard Dry Dock shipyard in 1943 and owned by the Park Steamship Company, a Crown corporation—was alive with activity, as was much of Vancouver Harbour on that overcast Tuesday. On Pier B.C., where Green Hill Park was berthed, loading had almost been completed ahead of its voyage to Australia.

The ship’s cargo consisted of lumber, newsprint, tinplate and aircraft parts, as well as about 108 tonnes of sodium chlorate—a weed killer—in 2,000 steel drums, seven tonnes of pyrotechnic flares, 50 barrels of whisky and a considerable number of mustard pickle cases, among other items.

Green Hill Park, named after a small provincial park in Nova Scotia, had braved enemy submarine-infested waters twice before, circumnavigating the world unharmed, excluding a bar fight in South Africa that the teenaged Conway-Brown remembered all too well.

But there was little time to recount such tales when the unmistakable sound of commotion came from the deck. Someone shouted, “Fire at number three hatch!”

Conway-Brown, whose duties as a seaman included serving as a firefighter, sprang into action and headed for the hold, one of Green Hill Park’s six compartments that were located amidships under the bridge and forward of the engines. By the time he had reached the fire hose, however, it was too late.

Longshoreman Ralph Atkinson had been the first to notice the ever-thickening wisp of smoke rising from No. 3 hold. When he raised the alarm, a mass of men clambered up escape-hatch ladders, while those on deck directed water toward hatch three.

Nevertheless, between 11:55 and 11:57 a.m., the efforts to fight the fire proved futile as the hold’s ’tween decks erupted in a shower of metal. A second explosion, more ferocious than the first, followed between 11:57 and 11:59. Thereafter two more blasts caused the vessel to spring up and down, sending steel fragments into the sky before raining down on the crew.

The ship’s sides peeled back with each detonation, the bridge crumpled in on itself and, below, the bulkhead between No. 2 and No. 3 holds was thrust outward. The smell of smoke quickly became tinged with the incongruous scent of pickles, cases of which had been splayed across the harbour.

The subsequent shockwaves stretched beyond Green Hill Park to shake downtown Vancouver. Nearby dockyard workers and pedestrians were knocked off their feet, then barraged by a hailstorm of shattered glass that swept through nearby buildings and streets.

Reporters at The News-Herald became aware of the soon-to-be story when the windows of their editorial rooms rattled. Meanwhile, the trembling office of labour lawyer John Stanton suggested to him that something terrible had happened on the waterfront. A client within earshot compounded the sentiment when they invoked the 1917 Halifax Explosion, a munitions catastrophe that had claimed nearly 2,000 lives during the First World War.

Fellow Vancouverites might have been forgiven for wondering the same when a dark mushroom cloud began rising above the city.

Conway-Brown opened his eyes to an inferno. There was no time to stare in horror, so he ran for shelter beneath the upper gun deck alongside other crew members hiding from falling debris. The survivors scoured their surroundings for a potential escape route, but there was no appealing option short of jumping overboard to an uncertain fate.

Meanwhile, 17-year-old Seaman Alfred Coombs was prepared to take his chances. He had been close to No. 3 hold when the initial blast had flung him against the galley. Now at the bow, he jumped over the side, then clung to a stowed anchor. He managed to grasp a hanging rope and shimmied himself into the water. Once there, though, another man fell on top of him, sending him under the oil-spattered waves.

Gasping for air, Coombs surfaced into a sea of blackened driftwood. A breakwater log floated within swimming distance, which he made for amid the carnage of Green Hill Park’s stowed flares, set off by the blaze and firing off in every direction. He hid until the cacophony subsided.

Finally, Coombs headed for the wharf and was hauled onto dry land. Yet he soon felt numb, his legs started to fail him and he collapsed into the arms of a firefighter. The nearby rescuers removed his clothes, provided him with a blanket and caught the attention of an ambulance to help treat his shock and eventually transport him to St. Paul’s Hospital. He was in safe hands.

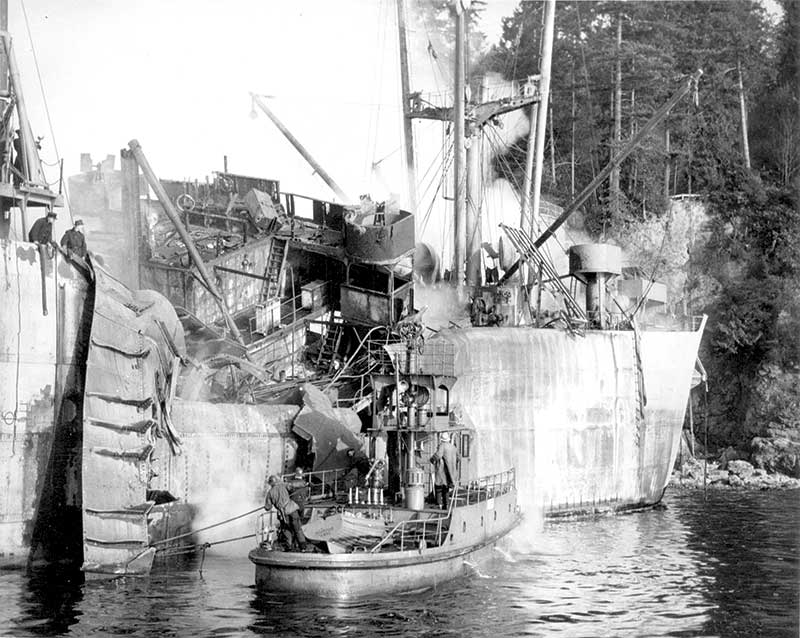

A fire boat attends to the smoldering Green Hill Park.[im Fairley/City of Vancouver Archives/CVA 1376-686]

Investigators explore the ship’s interior.[Don Coltman/City of Vancouver Archives/CVA/586-3615]

Safety was far from a guarantee back on the stricken Green Hill Park. With its lumber cargo caught in the explosion’s ensuing flames, the fear of imminent death crept into the souls of everyone still aboard.

Hope arrived in the form of the harbour rescue craft Andamara, operated by Able Seaman Neil MacMillan. Mere minutes after the blasts, the small ship was stationed under its larger, crippled counterpart, ready to receive survivors who slid down ropes from above, including a grateful Conway-Brown.

More vessels were en route to help, the tugboat R.F.M. operated by Captain Harry Jones, one of the first among them. It would be joined by Glendevon, Squamish, Maple Prince and an unnamed aircraft vessel for the swiftly drawn plans to remove Green Hill Park before she inflicted further destruction to the waterfront or worse.

The journey, fraught with risk for the tugs, took them beneath the Lions Gate Bridge, past Prospect Point in Stanley Park and to Siwash Rock. Accompanied by the fire boat J.H. Carlisle and the fire barge Louisa, the escorting entourage managed to beach Green Hill Park at Siwash Rock, whereupon thousands of tons of water flooded it. Still, the ship remained ablaze and smoldering for two days.

In the Green Hill Park disaster’s immediate aftermath, numerous Vancouver residents feared an enemy attack had transpired.

This was not the Halifax Explosion in size or intensity, nor was it comparable to the more recent Bombay (Mumbai) Explosion of 1944 that had devastated the Indian port and killed between 800 and 1,300 people.

However, the damage wrought was extensive, the Vancouver Sun later remarking that the Canadian Pacific Railway docks “looked nothing less than a scene from war-torn Europe.”

There were some minor similarities to the Halifax Explosion, not least that in the Green Hill Park disaster’s immediate aftermath, numerous Vancouver residents feared an enemy attack had transpired—except that the Japanese were the prime suspects on Canada’s West Coast rather than the Germans blamed on the East Coast 30 years earlier. In neither instance was an enemy bombing the case, with both theories refuted in due course.

Thankfully, though still tragically, the death toll would not mirror Halifax in that eight had perished aboard the vessel—longshoremen Donald G. Bell of B.C., 34; Joseph A. Brooks of N.B., 51; William T. Lewis of Wales, 46; Merton McGrath of N.S., 46; Montague E. Munn of P.E.I., 57; and Walter Peterson of N.B., 56. The seamen killed were Julius Kun of Hungary, 41, and Donald Munn of Scotland, 54. Most had died of fourth-degree burns, their bodies unrecognizable when they were retrieved from the ship.

Conway-Brown was one of the lucky ones. He had lost his personal belongings and money, but he walked from Andamara’s deck and into the city, traipsed across the Cambie Bridge toward West Coast Shipbuilders, and told his father, who worked there, that he was alive.

A local surveys damage to a nearby building from the blast. [Don Coltman/City of Vancouver Archives/CVA/586-3593]

Sabotage, incendiary bomb, friction and spontaneous combustion were all proposed as causes of the explosions in the hours, days and weeks after the incident.

The Green Hill Park was refloated, repaired, resold and renamed (Phaeax II and Lagos Michigan, respectively) under different owners before it was sold for scrap in 1967. But in the immediate aftermath of the explosions, tensions remained high.

Canadians demanded answers; their protests, amplified by the International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union and the Canadian Seamen’s Union, would result in a full inquiry.

The hearings opened on March 26, just weeks after the explosion. They were presided over by Justice Sidney Smith, Captain Samuel Robinson and Steamship Inspector Hugh Robinson (unrelated to his colleague).

Representing the unions was John Stanton, the labour lawyer whose office had been shaken in the shockwaves. He, alongside his colleagues, intended to piece together the events that led to the explosions and, perhaps, lay blame at the feet of the 22 individuals named as parties.

Over 18 sessions, the inquiry determined that there were indeed a significant number of parties at blame, some of whom hadn’t been named as such at the beginning.

Green Hill Park’s Captain John Wright had escaped formal declarations of potential culpability, but he volunteered a story in which he admitted overlooking the knowledge that sodium chlorate was a hazardous material that shouldn’t, under any circumstances, be stowed with combustibles. Subsequent statements by the ship’s master alluded to a lax attitude and more serious shortcomings on that fateful day.

Furthermore, Port Warden Captain Carl R. Bissett, a named party, had been responsible for inspecting ships and their cargo to ensure they met regulations for seaworthiness. Upon checking No. 3 hold ahead of departure, he signed off on what he perceived to be satisfactory stowage. In reality, handbook rules decreed that no more than nine tonnes of sodium

chlorate should be allowed in any one hold—there were 12 times that in the compartment.

Chief Officer Alan Horsfield, meanwhile, had the authority to overrule loading plans, though he was deemed ignorant of the cargo’s dangers. He had shown gallantry by staying aboard the burning ship with two crew members to secure towing lines, a factor that probably saved him from the inquiry’s full ire. He, along with Carl Bissett, Canada Shipping Company’s acting manager Kenneth M. Montgomery, its marine superintendent Alexander S. Galt, its marine supercargo Charles T. Heward and “one or more longshoremen working in No. 3 ’tween deck,” were instead censured for their involvement. The non-party Capt. Wright was said to be “gravely in default” during the proceedings.

The Green Hill Park explosion left debris throughout the vicinity.[Don Coltman/City of Vancouver Archives/CVA/586-3597]

The commission had heard enough testimony to recognize the role of human error in the four blasts that had rocked Vancouver. Its attention now turned to mistakes not previously suggested that could have caused the explosions.

The ship remained ablaze and smoldering for two days

Fifty whisky barrels in relative seclusion sparked curiosity as thoughts drifted to what sparked the fire. Could it be that someone had broached the liquor, lit an open flame and accidentally dropped it?

Little in the way of concrete evidence could prove that siphoning had taken place, and the notion alone incensed the longshoremen.

Still, in the eyes of legal authorities, the discovery of a jacket with hot water bottles sewn inside and lunch pails with specially soldered compartments for holding liquids made a compelling case that there had at least been an intent to broach the overproof and inflammable alcohol.

Concluding the inquiry, the official report stated that “…we think there was…a space giving access to the whiskey barrels, and that it was here that a match was lit and through some unhappy chance was dropped.”

In 1980, a 91-year-old longshoreman made an admission. When he and another dock worker found themselves in the hospital together in the 1950s, the second man confessed that a passage had been cleared to the liquor on Green Hill Park, allowing room to siphon and drink in secret. Whisky, he explained, had been spilled on the floor by an inebriated longshoreman, who proceeded to strike a match to see better.

An uncovered truth or a mere rumour? Regardless, the cause of the Green Hill Park disaster remains a mystery.

Workers load destroyed cargo from the ship onto a barge[Don Coltman/City of Vancouver Archives/CVA/586-3614]

Advertisement