A satellite such as this one is used by the COSPAS-SARSAT satellite rescue system to detect and locate radio signals from aircraft and ships in distress.[iStock]

Many light aircraft downed by equipment failure, turbulence or unexpected foul weather have disappeared, crashing among the peaks and dense forests of the mountainsides and valleys. Some have never been found.

On July 19, 1982, a small craft piloted by Jim Heemskerk disappeared on a flight from Dawson Creek to Dease Lake in northeastern British Columbia. After seven fruitless weeks and nearly 1,800 flying hours costing about $2 million, the Department of National Defence called off the search.

The plane stalled and crashed in a heavily wooded area.

But George Heemskerk, the father of the missing pilot, did not give up.

On Sept. 9, he and a friend went searching aboard a Cessna 172 with pilot Jon Ziegelheim when at about 11 a.m. the sunny weather, as it is wont to do in the mountains, suddenly turned foul.

The Cessna 172 was introduced in 1956 and is still in production to this day. It is one of the most popular aircrafts in history. [iStock]

“We pitched over and hit the ground almost vertically at about 40 miles [64 kilometres] per hour,” said Ziegelheim.

The pilot suffered a broken leg, the father had a broken arm and the friend had broken ribs. The antenna on the emergency location transmitter had broken off. So at about 3 p.m. the survivors hauled the transmitter up a hill and stuck the antenna straight into it in hopes of improving reception for their distress call.

The flight was soon listed as overdue and a Canadian Armed Forces search-and-rescue squadron in Comox began fruitlessly searching along the track of the flight plan. Since the plane went down about 50 kilometres off its intended route, it could have been days before it was discovered, if ever.

The mountains of Rogers Pass in British Columbia are known as the one of the snowiest regions in Canada. [iStock]

In Canada on Sept. 10, 1982, just a few days after the satellite’s repeater was activated for testing, the orbiting satellite identified two possible search areas, and a plane circling one location picked up the transmission from the survivors. Search-and-rescue technicians, known as SAR techs, parachuted to the site.

“We were amazed that they had found us so soon,” said Ziegelheim. “That’s when they told us a satellite had rescued us. What satellite? They told us that an international program had devised a SAR satellite, however it was only in the test stage and had just been turned on. This was the first time they had used it. Fortunately for us it worked! That’s when they told me it was a good thing it did because I would have bled to death within the next day.”

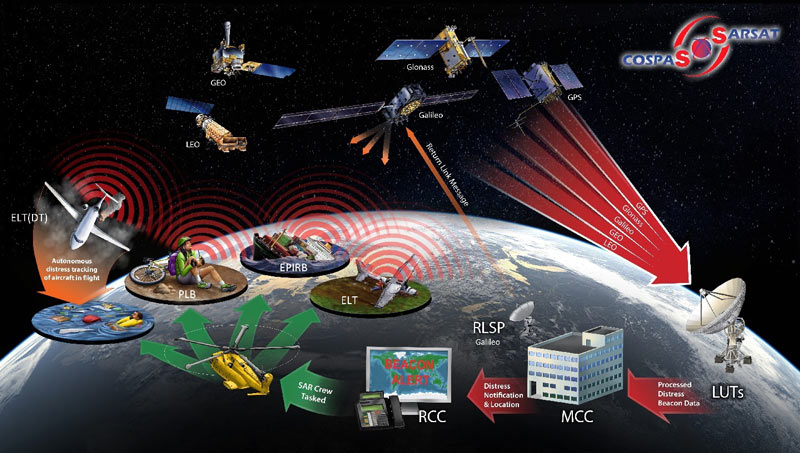

Since 1982, the COSPAS-SARSAT satellite rescue system has expanded to include more satellites and dozens more countries.

Once a plane, ship or person activates an emergency beacon on a certain frequency, satellites pick up the signal and relay it to a rescue co-ordination centre, which in Canada calls in search-and-rescue teams that are on duty 24 hours a day.“The system really sees the whole world,” Major Alain Tanguay, then of the Canadian Mission Control Centre in Trenton, Ont., said in a 2007 article in The Contact newsletter. “When it comes to [search-and-rescue] operations, the name of the game is speed,” he said.

“When an emergency situation happens, such as a plane crashing or a boat getting caught in rough seas, people are in distress, they are in danger. We need to get a team out there as soon as we possibly can. The information and direction we get from the COSPAS-SARSAT system allows us to do that.”

The satellite search-and-rescue system has saved more than 46,000 lives on sea and land around the world since 1982.

Advertisement