HMCS Sioux negotiates sea ice in February 1952. [DND/LAC/PA-138217]

The 1950 invasion by North Korea drew world-war allies, including Canada, into another fray

Two days after North Korean troops unexpectedly invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, the United Nations called on its members for help to stop the attack and restore peace. Canada’s first military response was to send in the navy.

On a peacetime footing, neither the army nor the air force could quickly deploy 11,000 kilometres overseas. But Royal Canadian Navy destroyers had been preparing for deployment for NATO manoeuvres, and three were anchored in Esquimalt, B.C.

On July 5, HMC ships Cayuga, Athabaskan and Sioux set sail, the first of eight Canadian destroyers and 3,621 naval personnel to serve in the Korean War.

“They drafted 90 of us ordinary seamen from our training…to the three destroyers,” recalled Ken Kelbough, in one of many Memory Project interviews cited in this story. “I ended up…on Sioux, which I was very happy about because it had bunks compared to the hammocks.”

Four more Tribal-class destroyers—HMC ships Nootka, Huron, Iroquois and Haida—as well as the Crescent-class destroyer HMCS Crusader served until after the armistice in 1953.

By the time the first three ships, under command of Captain Jeffry Brock, joined the UN naval force on July 31 in Sasebo, Japan, North Korean invaders had captured Seoul, South Korea’s capital, and nearly driven its army into the sea.

The UN drew a 230-kilometre defensive perimeter around the port of Pusan (now Busan) and fighting was fierce to maintain and expand that toehold. The Canadian ships were immediately put to use.

“We were only there less than a day and there was an emergency,” recalled Reginald Vose of Athabaskan. Troops were urgently needed. Athabaskan and Cayuga were assigned to protect aircraft carriers and convoys while Sioux was given rescue duties, including plucking crew from the sea after an aircraft crashed or ditched.

Soon the Canadian ships were reassigned to blockade and patrol duty, prowling the coast and islands, searching junks and sampans that might be armed or sneaking supplies to North Korea.

Anti-aircraft crew members on a Canadian destroyer keep watch. [Donald M. Stitt/DND/LAC/PA-126625]

In mid-August, UN ground forces were fighting inland from Busan and out of range of help from naval guns. Enemy forces had seized the port city of Yeosu, on the southern coast, and it was decided the navy would deprive them of its use.

For the first time since the Second World War, a Canadian ship engaged an enemy. On Aug. 15, Cayuga joined HMS Mounts Bay bombarding warehouses and port installations, “Cayuga herself placing 94 rounds of 4-inch high explosive,” wrote Thor Thorgrimsson and E.C. Russell in Canadian Naval Operations in Korean Waters 1950-1955 (CNOps).

All three Canadian ships helped protect the UN force’s flank in the surprise attack on Inchon on the west coast in September. The port was seized and UN troops pushed inland to liberate Seoul on Sept. 26, then drove North Korean forces back over the 38th parallel, collecting 125,000 prisoners.

It seemed the end of the conflict was nigh. But ignoring warnings from China, UN forces crossed the border into North Korea and captured its capital Pyongyang, then advanced to the Yalu River, the boundary with China.

As threatened, China sent troops to fight alongside North Korea, their combined forces strong enough to push UN forces back across the 38th parallel, then on to reclaim Pyongyang.

Captain J.V. Brock (inset) speaks with Korean officials after the amphibious invasion of the port city of Inchon in September 1950. [LAC/E011066934]

On Dec. 4, Brock, now in command of six destroyers on blockade duty along the west coast, was tasked to cover the evacuation of Nampo, the port on the Taedong River supplying UN forces fighting in Pyongyang.

“Between the warships and the city lay 40 miles [64 kilometres] of tortuous navigation through a shallow swept channel that was bordered by minefields, shifting mud banks and treacherous shoals…difficult enough by daylight;” odds were heavily against them “on a moonless night, with winds and strong tides adding to the hazards,” says an account of the events in the January 1951 edition of The Crowsnest.

After dark in a winter rain at low tide, the six destroyers cautiously crept up the river. “It was as black as the inside of a cow,” reads Brock’s log entry. At times, there were only 20 inches [50 centimetres] of water beneath the keels, reported Ted Barris in a 2003 article in Legion Magazine.

Spotters on deck scanned the water for mines and floating dangers.

“It’s only 600 yards [548 metres] wide, that channel, and there was two ships went aground,” recalled Vose. “We went up there using the echo sounder and the radar and doing a lot of plotting.” Furious plotting, in fact.

The responsibility was heavy on Lieutenant Andy Collier on Cayuga, which was leading the armada. In four hours he made 132 “fixes,” or reports for realignment of the ship’s position, while spotters on deck scanned the water for mines and floating dangers, data vital for Brock to lead the four remaining destroyers safely in. Collier was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

HMCS Nootka replenishes ammunition from a U.S. navy supply ship.

“The accuracy of his navigation undoubtedly played a large part in ensuring the success of the entire operation,” reads the citation.

More than 8,500 military personnel and civilians fled the port, the last as enemy snipers started shooting in the town. While Athabaskan was sent downriver to secure the retreat, the three remaining ships rained about 800 shells to delay the enemy from using the port.

In January 1951, Canadian ships came under enemy fire for the first time. The Chinese pushed UN and South Korean forces farther south, and reclaimed Seoul on Jan. 4, 1951, and then Inchon, the port that supplied it. Canadian destroyers joined in subsequent UN bombardment of Inchon and on Jan. 25, Cayuga and newly arrived Nootka were targeted by shore batteries, emerging unscathed.

As the war raged ashore, Canadian destroyers were regularly rotated in and out of Korea, assigned to either east or west coast command. There were no great naval battles, as North Korea had no great ships and its gunboat navy had been destroyed in July 1950. But that does not mean Canadian ships’ guns remained silent.

By the end of the war, Canadian ships “fired a total of over 130,000 shells at a wide variety of targets,” wrote Fred Fowlow of Athabaskan, in an article for Starshell in 2011.

“We caught a train between tunnels and destroyed all the boxcars.”

“I knew our barrels were really worn out because [shells] would make a noise, a fluttering noise, as they flew away,” recalled gunnery officer Philip George Bissell of Sioux. “And by the time we got back to Canada, our [once] nice, brand-new barrels of 4.7, now 4.9 inch, would shoot back at us.”

Canadian ships supported land operations when required, guarded aircraft carriers, did sea rescue work, curtailed enemy movement by sea, escorted troop and cargo ships, shelled shore installations and railway lines, helped during evacuations, and provided humanitarian relief. All the while they were on alert for mines, which sank or damaged 11 UN ships, none of them Canadian.

Against this background was the daily grind of patrols in the Yellow Sea on the west coast, the Sea of Japan on the east coast and the Korea Strait, which separates South Korea from Japan. And with patrols came danger from land, water and weather.

Troops from the Royal 22nd Regiment share tight quarters aboard a transport ship en route to Korea in March 1952. [Paul E. Tomelin/DND/LAC/PA-128858]

“We would go [on patrol] three to six weeks at a time,” recalled Kenneth Snider of Iroquois. “We had armament ready at all times. At night, we would anchor out and we had armed guards walking around the upper deck and then also had a 40-millimetre Bofors gun armed, and a crew. You had to sit by that gun…for your four-hour watch and be ready in case there were any problems.”

Such problems included enemy covert action. Chinese and North Korean vessels would come down the coasts to drop off agents or spies. Or lay mines.

“We had to be very careful,” recalled Earl Page of Huron, “because they would come alongside and blow themselves up.” Or lob in a grenade.

In mid-May 1951, a patrolling destroyer came across a Chinese fishing fleet in restricted water off the west coast. Not all carried fishermen.

Radar operator Don Jatiouk of Nootka spotted a minelayer. The captain skirted the minefield and captured the enemy crew. The next day a UN minesweeper neutralized the field. There was “a tremendous explosion…at least 250 feet [60 metres] in diameter and straight up in the air for at least 150 feet [45 metres],” wrote Jatiouk. “I’m certain that if we had run over that mine, the ship would have been lost…with probably heavy casualties.”

Wild winds, waves and weather claimed some. The first was Vince Liska, 29, of Cayuga on Dec. 4, 1950. R.E. Elvidge of Athabaskan was in the water for 15 minutes before being rescued during typhoon Clara in November 1950. One year later, shipmate Robin Skavberg, 20, disappeared from the ship off the west coast and could not be found in heavy seas and strong currents.

HMCS Crusader wins the UN Trainbusters Club championship in April 1953 in this painting by David Landry. [David Landry/CWM 19860128-002]

On the east coast, patrols frequently targeted rail lines. North Korean forces were supplied in part by a railway line forced by the rugged Taeback Mountains to run along the coastline, in places within range of naval guns. In one area, the line ran through a series of five tunnels. Each segment of track and tunnel was called a package. “We caught a train between tunnels and destroyed all the boxcars,” recalled Norman Heide of Sioux.

“At night, in the dark, they’d shut down everything onboard the ship and just glide along the coast…listening to see if they heard a train or whistle.” If they did, up went a star shell, flooding the sky with light so gunners could aim and “hit it before it heads into a tunnel,” recalled Daniel Kendrick of Huron.

The Trainbusters Club, a morale-boosting gunnery competition, was formed in July 1952. Many UN ships could claim hits on boxcars and rail lines, but membership was granted only to those ships that destroyed the train’s engine. It was a rather exclusive club, as guns were aiming for fast-moving targets, at maximum range, sometimes in foul weather or with the coast obscured by smoke—and often while under fire or on choppy seas.

“It was quite an achievement truthfully because the ship is going up and down, you’ve got to get your guns…right exactly where the train is, or just below a bit, to destroy the track and knock it off. And it became quite a feat,” said Haida gunner Jim Wilson.

“The Canadian ships entered into the spirit of this game with the greatest enthusiasm, and before the end of hostilities, had destroyed proportionately far and away more trains than had the ships of any other nation,” says CNOps.

“If you’re stuck in the ice, you’re a sitting duck.”

Of the 28 kills registered by the club, eight were credited to Canadian ships. Haida and Athabaskan were both elite “two-train ships” in the competition; Crusader’s gunners had the record: four trains hit, with three destroyed in one 24-hour period. “We had some of the finest gunners in the Canadian navy,” said Irving Larson of Crusader.

A boat would spot the trains, then radio the ship to prepare and “our guns were already loaded ready to fire, just as soon as they got into that package,” said Kelbough. “The guns would level off and then foooom, foooom blew them up.” Then “we had to get out of there because they would bring up shore batteries and you’re a sitting duck on a ship.”

So Iroquois discovered on Oct. 2, 1952, when it was hit broadside by shore batteries, at the cost of three dead and 10 injured. Iroquois was the only Canadian ship to suffer losses from enemy action (see page 86).

Sioux’s Bissell remembers an attack on the rail yards in the port of Wonsan in 1951, the first time the ship had a spotter aircraft.

“I said ‘this is our only chance to show off.’” The first shot “hit right in the middle of this factory…where they were assembling all their trains.” The suitably impressed spotter confirmed a direct hit, which was followed by 10 more in quick succession, obliterating the building and nearby trains, followed by shelling “that caused a great loss to them because that was the main routing of all their military armament.”

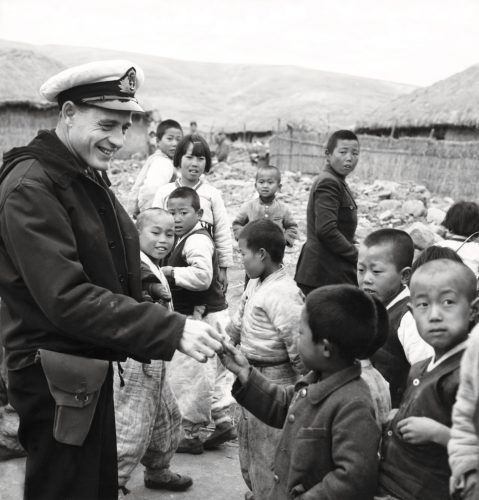

An ordnance officer from HMCS Nootka distributes candy to Korean children. [DND]

On the west coast, patrols kept constant vigil on the myriad islands, which were of strategic value to both sides.

North Korea wanted to expand the number of islands under its control, from which it could launch attacks and spy operations. The UN wanted to protect islands occupied by South Korea, some serving as bases, intelligence centres or radar posts, some housing refugees and a few held by friendly guerillas who continually attacked the mainland and passed on valuable intelligence.

Defence of the islands “became the most important and certainly the most dangerous and exciting of the many duties of the Canadian destroyers on the west coast after the truce talks began,” according to CNOps. Action heated up whenever truce talks sputtered.

It was not an easy task making way through narrow navigable channels littered with rocks and shoals and plagued by strong currents.

“Wherever there was an inshore route used by the UN ships, the enemy sited batteries of field guns,” said CNOps. If a ship grounded in the night, “the morning might find her under the very muzzles of a strong battery.”

“We were always in close proximity to the 38th parallel…under [enemy] guns,” recalled signalman Ron Kirk of Iroquois. “Our job was to make sure the islands were still secure.”

They did that by “sailing around them slowly to make sure that [the enemy wasn’t] coming…across on the narrow waterway,” said Orrick. Much of the work happened at night.

“Your job in the daytime was to protect [an aircraft] carrier with our guns. The threat of submarines always existed,” said Bissell of Sioux. But after dark, “most of the time we were trying to stop the North Koreans and Chinese from island-hopping.” At dawn, the ship would return to escort the carrier.

The conditions so unfavourable for UN ships were perfect cover for the enemies’ small vessels. UN patrols intercepted many junks.

“Some were armed and some weren’t. You would go alongside or bring them alongside and inspect them and question them,” said Eldon Davidge of Crusader.

Sometimes Canadian ships were called to duty in the labyrinth of islands in Haeju Bay, above the 38th parallel, in range of enemy guns. Cayuga “was responsible for the initial organization of the Haeju naval defence unit,” says CNOps, which included “defence of the friendly islands, helping guerrillas dislodge invaders from recently captured islands and dealing with the huge number of refugees.”

Canadian ships bombarded ports, pillboxes and observation posts, took part in raids and gathered intelligence. Cayuga dropped off two crewmen to observe enemy ships, but their overriding concern was to not become prisoners of war.

“We were scared to death,” said signalman Scotty Wells. “We climbed up as high as we could. We didn’t walk around the island and hid as much as we could. That’s probably the most nerve-racking day we had.”

Sailors on HMCS Sioux chip ice from the deck. [Legion Magazine Archives]

Navigation was tricky among the shoals and shores of the islands and mainland on the coast in all weather. Huron was patrolling in fog on the night of July 13-14, 1953, “in an endless figure eight” near the island of Yang-do, which was used by the Americans and South Koreans for intelligence gathering. There was a jolt.

“The forward part of the ship was resting on top of large rocks. Huron had run aground!” recalled George Schober. The ship was worked off the rocks and towed stern-first for repairs.

In winter, ice was a problem. “The ice was not the kind of ice we have in the Arctic,” said Robert Orrick of Athabaskan. It was thin enough to be broken into small pieces by the ship’s passage, with the danger it could get caught in intakes below the waterline. “If we got ice jammed against an intake, we’d be in trouble; we wouldn’t be able to move…and if you’re stuck in the ice, you’re…a sitting duck” for enemy guns.

Patrols often came across starving and destitute refugees.

“The men…did what little they could to alleviate the sufferings of these unfortunate people,” said CNOps. Commander Robert Welland of Athabaskan reported that “the pathetic state of the occupants in the bitter cold weather brought forth showers of cigarettes and trifles from the hands on the upper deck whenever a junk was brought alongside.”

“When we realized there was something we could do, usually we’d do a collection,” said Kirk of Iroquois. “I remember writing home and asking my mother to send me over baby clothes.”

“They didn’t have much to eat,” said Donald Raven of Crusader. “They’d spend all day going out to the rocks, picking meat out of barnacles for food.” He and shipmates would fill their pockets with mini boxes of cereal and give them to kids, and hosted a party for some orphans aboard ship, then raised money to buy material to make them clothes.

“On a couple of occasions, we…found civilians in pretty rough shape, so our captain, Jeffry Brock, started a movement to bring food to the different islands,” recalled Jim Dockstader of Cayuga.

“I’ve never seen such poverty,” remembered Karl Ryckman of Huron. “Some of the time they’d have no clothes to wear.” The ship would donate “food stuffs or clothes…a lot of hand-me-down stuff from the guys on board.”

The humanitarian work continued after the armistice on July 27, 1953, as hundreds of thousands of refugees dislocated by the war escaped from North Korea and sought a new place to live, many dying in the attempt.

Canadian destroyers policed the ceasefire and helped with the evacuation of islands to be returned to North Korea. Everyone was uneasy. Haida was on observation duty in the Han River estuary near Seoul, making sure there was no arms build-up or aggressive action.

“Sitting under the communist guns…you’re just hoping that they know that there’s a ceasefire in effect,” said Haida’s Andy Barber. “It wasn’t unusual for us to close up to action stations. They did buzz us once or twice…just to let us know they thought we were encroaching upon their land…we’d have to weigh anchor and get the heck out of there.”

In September 1955, HMCS Sioux sailed home, the last Canadian destroyer to serve in the Korean theatre.

Of the 30,000 Canadians who served in ground, naval and air forces during the Korean War, there were 516 deaths and 1,557 physical casualties, not counting mental health issues. The Royal Canadian Navy lost nine—four killed in action, three lost at sea and two in an air crash at sea.

Joining the navy, said Kirk, “was probably the best decision I ever made. I never knew why until 57 years later when I went back to Korea,” and was struck by the stark contrast between the modern, successful society and his memories of its destitute people during the war.

“It was unbelievable. It’s a vibrant country. The infrastructure—wow, I couldn’t get over it. Their whole life, especially to Canadians, is ‘Thank you.’”

Advertisement