Refugees who fled Lodz, Poland, two months earlier make their way toward Berlin in 1945, following rail lines in the hope of being picked up by a British train. [Fred Ramage/Getty Images]

The end of the Second World War in Europe led to celebrations in Allied cities the world over, but for many Europeans devastated by tragedy and loss over six long years of conflict, the continent must have seemed a post-apocalyptic wasteland. It was no place for celebration.

The cost of fascism’s march across Europe and subsequent occupations was exacted on non-combatants more than anyone. Fewer than 30 per cent of the 85 million people killed during the war were military, and the vast majority were citizens of Allied countries—

primarily the Soviet Union and China.

The war spawned 11 million refugees in Europe alone. Many had nowhere to go. Entire cities lay in ruin; some towns and villages had disappeared altogether.

Vast swaths of the Netherlands lay underwater, flooded by both sides in the desperate dying days of the war. Soviet Russia had enacted a scorched-earth policy ahead of the German advance across the steppe in 1941, and retreating Wehrmacht adopted similar practices as they withdrew under the relentless Red Army counteroffensives of 1943 and 1944.

The infrastructure of an entire continent was in ruin or in disarray. Roads and bridges had been destroyed. There were no phones, telegraphs, postal services, rail systems. Sewer and water services were non-existent in many areas. Sprawling factories and thriving enterprises that once drove the economies of Europe had been demolished or plundered.

There was not enough food. There was not enough of anything, not even enough tools and machinery to rebuild. Governments were in disarray. Leadership was in flux. Law and order had dissolved.

But there was more than enough anger, despair, resentment and bitterness.

Haunted and emaciated, a former concentration camp prisoner awaits medical attention after being freed by Allied troops. [Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos]

Millions of people in Europe were impoverished, hungry and desperate, and a significant proportion of them were out for retribution, be it on German, collaborationist or any variety of ethnic or political rival for whom the war had opened an unprecedented opportunity to act on longstanding hatred.

“In some areas there no longer seems to be any clear sense of what is right and what is wrong,” wrote historian Keith Lowe in his 2012 book Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II, a groundbreaking examination of previously widely unknown factors that helped shape the present-day continent.

“People help themselves to whatever they want without regard to ownership—indeed, the sense of ownership has largely disappeared. Goods belong only to those who are strong enough to hold on to them, and those who are willing to guard them with their lives.”

Armed men roamed the streets, taking what they wanted and threatening anyone who got in their way. Women of all classes and ages prostituted themselves for food and protection.

“The story of Europe in the immediate postwar period is…primarily one of reconstruction and rehabilitation,” asserts Lowe. “It is firstly a story of the descent into anarchy…. There is no shame. There is no morality. There is only survival.”

There was looting, robbery, a thriving black market, vengeance and vigilante justice. Some feared a Europe-wide civil war. In some areas, fighting continued for weeks, even years, after VE-Day. Civil wars, ignited by Nazi involvement, raged in Greece, Yugoslavia and Poland for several years after the big one ended.

A view of Walcheren, Netherlands after the sea had roared in through gaps blown in dikes by RAF bombers in the campaign to drive the Germans out. [John Florea/Life Magazine/ LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images]

In Ukraine and the Baltic states, nationalists fought Soviet troops until well into the 1950s. Indeed, Soviet domination in eastern Europe led to the 44-year Cold War, punctuated by the Hungarian Revolution in 1956—and a resulting influx of Hungarian refugees to Canada—follow-ed by the Prague Spring and subsequent Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

The Iron Curtain was the most blatant and impactful case of spoils going to the victors. The map of Europe was being redrawn; the populace already had been.

There were 16.6 million Jews worldwide in 1939 and 9.5 million of them lived in Europe, reported The Pew Research Center in Washington, D.C. By war’s end, the continent’s Jewish population had been reduced to 3.8 million. The Nazi system of genocide was horribly efficient.

Today, the Jewish population in Vilinius, Lithuania, is just 10 per cent what is was before the war. Jews once comprised a third of the population of Warsaw, Poland; Red Army liberators found just 200 when they arrived in January 1945. In many places, centuries-established Jewish populations were simply gone.

Hitler ravaged Jewry, but failed in his ultimate goal of eradication. Judaism received a homeland in 1948. Today, the worldwide Jewish population is at least 14.6 million and thriving.

A Belgian woman identifies a former Gestapo informer who had tried to hide in the crowd at a German transit camp for refugees, political prisoners, prisoners of war and forced labourers in April 1945. [Henri-Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photos]

The Nazis didn’t persecute Jews only. Schutzstaffel (SS) chief Heinrich Himmler also presided over the systematic slaughter of six million mentally handicapped, homosexual, political, intellectual and other prisoners.

Alongside the Nazi regime of terror, the war presented other ethnic, religious and political communities across Europe the opportunity to settle old scores and cleanse populations of so-called undesirables.

In Croatia between about 1941 and 1945, the fascist Ustaše regime killed an estimated 592,000 Serbs, Muslims and Jews. After the Jews had been exterminated in the Volhynia region of central and eastern Europe, Ukrainian nationalists killed tens of thousands of Poles. Invading Bulgarians massacred Greek communities along the northern edge of the Aegean Sea, and Hungarians killed Serbians en masse in the Vojvodina region of Yugoslavia.

“In many areas of Europe, unwanted ethnic groups were simply driven out of their towns and villages,” wrote Lowe. “This occurred all over central and eastern Europe at the beginning of the war, as the old empires clawed back the territory they had lost in the aftermath of the First World War.

“During the course of just six years, the demographics of Europe had changed irredeemably.”

For many, the war’s end meant payback.

German PoWs are marched to Moscow. Many would never return. [Carl Mydans/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images]

“There are only two sacred words left to us. One of them is ‘love;’ the other one is ‘revenge.’” wrote Ukrainian Jewish author Vasily Grossman in October 1943. After liberation, Allied soldiers turned a blind eye to acts of retribution by concentration camp prisoners, who in some cases beat guards to death.

Lowe relates the story of Alfred Knoller, an Austrian Jew who was liberated at Bergen-Belsen. Knoller said British soldiers gave the freed prisoners explicit permission to raid local farms for food.

At one farm, Knoller and his fellow survivors found a Hitler portrait hidden alongside a barn. Inside, they found weapons. They smashed the picture, then took the rifles and shot the farmer and his wife dead.

“I know it was quite inhuman, what we’d done,” Knoller said later. “But…it was absolutely an act of revenge. It had to come out.”

Thousands of displaced persons, initially euphoric over their liberation, found themselves herded into refugee camps where conditions were often worse than what they had been subjected to in the war. Allied troops assigned to look after them encountered suspicion, cynicism, apathy and restlessness, rather than gratitude.

The Soviet advance westward was particularly bloody, fuelled by a gaping ideological divide and revelations of Nazi atrocities.

In Berlin, a Red Army soldier struggles with a German woman who refuses to sell him her bicycle. [Serge Plantureux/Corbis/Getty Images]

“Hitler’s ruthlessly waged total warfare had ended,” wrote Von Christian Habbe in Der Spiegel. “Now the time of retribution was dawning everywhere.”

To the Red Army’s ultimate detriment, women bore the brunt of it—which served only to deepen German resolve and stiffen its resistance in the east.

“Red Army soldiers don’t believe in ‘individual liaisons’ with German women,” the playwright Zakhar Agranenko wrote in his diary while serving as an officer in East Prussia. “Nine, 10, 12 men at a time—they rape them on a collective basis.”

Natalya Gesse, a close friend of the scientist Andrei Sakharov, observed the Red Army in action in 1945 as a Soviet war correspondent. “The Russian soldiers were raping every German female from eight to 80,” she recounted later. “It was an army of rapists.”

Historian Antony Beevor reports that Berlin’s two main hospitals estimated the number of rape victims in the German capital alone at 95,000 to 130,000. “One doctor deduced that out of approximately 100,000 women raped in the city, some 10,000 died as a result, mostly from suicide,” Beevor wrote in his 2002 book Berlin: The Downfall 1945.

German troops who surrendered on the eastern front—three million of them—were marched off to remote Soviet labour camps, many never to see their homes or families again. Almost 1.1 million died in captivity, according to German historian Rüdiger Overmans.

“Millions of Germans in eastern Europe met the same tragic fate, paying with life and limb for the crimes of Nazi Germany,” wrote Habbe. “They were hunted down, humiliated, raped, bludgeoned to death, or carted off as slave labourers.”

As the Allies advanced, they freed slave labourers who had been brought to Germany from all over Europe to work in factories and other enterprises. On their first taste of freedom in years, marauding groups of liberated workers found liquor and went on unchecked looting sprees, beating—even killing—locals along the way.

Vindictive neighbours and partisans shave the head of a French woman accused of sleeping with Germans during the occupation in a village near Marseilles. [Keystone/Getty Images]

“Revenge was a fundamental part of the bedrock upon which postwar Europe was rebuilt,” wrote Lowe. “Everything that happened after the war…bears its hallmark: to this day, individuals, communities and even whole nations still live with the bitterness born of this vengeance.”

Beyond the rivaly and hatred bred over generations prior to the war was the revenge exacted on collaborators after it ended. These included entire nations which were stripped of territory and assets, governments and institutions which were purged, and communities which were terrorized.

“A tempest of reprisal, revenge and hatred swept through the land,” wrote historian Klaus-Dietmar Henke.

Some of the worst retribution was saved for individuals, who were beaten, tortured, hanged or shot. Women who had slept with German soldiers were stripped, shaved and paraded through streets covered in tar.

Hundreds of Nazis and their collaborators would be tried, convicted and punished in postwar trials at Nuremberg and elsewhere. But for a time, in the immediate aftermath of the fighting, Allied soldiers disregarded acts of vigilante justice brought down on those who had informed and collaborated with the Nazi occupiers. In some cases, these incidents had as much to do with settling older scores as more recent ones.

“That Europe managed to pull itself out of this mire, and then go on to become a prosperous, tolerant continent seems nothing short of a miracle,” wrote Lowe. “Looking back on the feats of reconstruction that took place—the rebuilding of roads, railways, factories, even whole cities—it is tempting to see nothing but progress.”

“Far from wiping the slate clean,” he said, “the aftermath of the war merely propagated grievances between communities and between nations, many of which are alive today.”

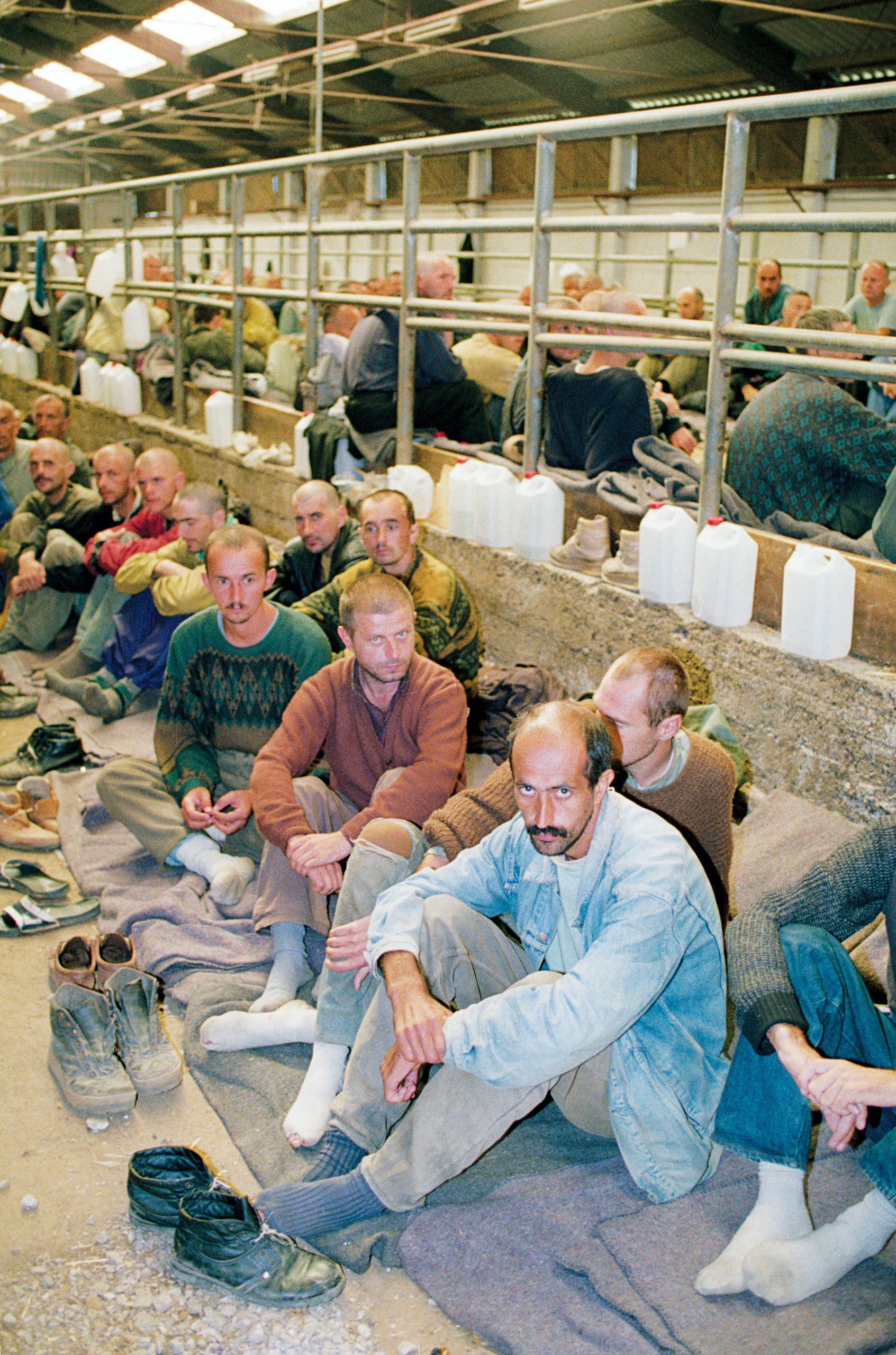

Muslim civilians captured by Serb forces in September 1992 are confined in a cattle barn-turned-detention camp in Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Serbs insisted the detainees were prisoners of war arrested during military hostilities, but none wore uniforms. [Agencja Fotograficzna Caro/Alamy Stock Photo]

Civil war raged on in Greece for four years after the war. Soviet aggression and dominance in eastern Europe spawned new wars, revolutions and revolts. Guerilla war in the Baltic states spanned 12 years.

Some Poles contend that the Second World War did not end until the last Soviet tank left the country in 1989. Poland “emerged as the heaviest loser on the winning side,” historian Andrzej Suchcitz once told the Polish Ex-Combatants Association in Great Britain.

“At Tehran in the autumn of 1943, Poland was handed over by her Western allies to Soviet rule,” Suchcitz wrote in 1995. “The Yalta conference only confirmed this act of betrayal for Poland and her people.

Members of the Canadian NATO contingent in Latvia fire a missile during range practice in January 2018. The alliance has stationed troops throughout the Baltic states to discourage Russian aggression. [Sergeant Bernie Kuhn/Task Force Latvia]

“VE-Day did not sound the bells of victory and a time of peaceful reconstruction. It ushered in a new foreign occupation in which the new Poland, robbed of half her territory annexed by the U.S.S.R., found herself under the Soviet heel…. The struggle continued for a further 45 years until true independence was once more restored in December 1990.”

The breakup of the Soviet Union and its satellites in the second half of the 1980s exposed the soft underbelly of totalitarian rule in eastern Europe. No fewer than 22 primarily nationalist- and ethnic-based conflicts have broken out in former Soviet states and satellites since the collapse of communism.

Among the most recent is in Ukraine, where the strategic Crimean Peninsula was annexed by Russian President Vladimir Putin in 2014. Russia has since sponsored a civil war between Russian-speaking separatists (aided by incognito Russian troops) and ethnic Ukrainians.

Second World War hero Josip Broz Tito ruled Yugoslavia with iron-fisted benevolence from 1953 to 1980, declaring that no one questioned “who is a Serb, who is a Croat, who is a Muslim [Bosniak]; we were all one people.”

With his death in 1980 and the collapse of communist governments across the Soviet sphere a decade later, Yugoslavia dissolved into ethnic hatred, murder and war. Its territorial spawn—Croatia, Kosovo and Bosnia—came to symbolize suffering and war crimes reminiscent of the Nazi tyranny.

Entire villages were wiped out, women raped, men tortured, homes burned, wells poisoned and crops destroyed. Cattle were slaughtered in the fields. Atrocities were committed by all sides. There were even concentration camps, where thousands of emaciated Croats and Bosniaks died by Serb hands.

It was an eye-opening end to the Cold War era. During that half-century, the Iron Curtain had shielded and contained a long and tragic history of ethnic hatred, a simmering stew waiting to boil over.

In the final decade of the 20th century and into the 21st, the Allied nations of the Second World War—including Canada—were back patrolling European soil, this time alongside Germans and former Axis allies wearing United Nations blue.

Canadian troops are now in Ukraine, training domestic forces under the NATO flag, and leading an expanded mission in Latvia, one of several NATO deployments aiming to discourage Russian aggression among states bordering the Baltic Sea.

History is not always a catapult to progress. Human cruelty has not gone away. In many cases, old hatreds and rivalries still seethe, occasionally erupting in violence or something more subtle but still cruel.

Among some of the world’s mightiest nations, a determination for conquest remains a threat to world peace. Meanwhile, the oppressed fight to rise from poverty and the old world order, demanding their rightful place in the 21st century. Mass movements of peoples from places of perpetual war, drought, poverty and hunger have given rise to xenophobic pushback and nativism across Europe and here in North America.

Fortunately, the world’s response to such tensions—largely via alliances that grew out of the Second World War and the subsequent Cold War—tend to be more evolved, measured, and tempered by history. But one thing remains certain in an uncertain world: the march of history will not be denied—two steps forward, one step back.

Advertisement