Photographs and story by Stephen J. Thorne

With more than 75 million estimated to be in circulation, the Avtomat Kalashnikova, or AK-47 (for the year Mikhail Kalashnikov completed his work), is the most popular and most copied weapon in the world. Light, simple, reliable and stable, the AK-47 has for decades been the weapon of choice among revolutionaries, insurgents, terrorists and resistance fighters in virtually every corner of the globe. Easy to maintain and easy to use, it is ideal for marginally trained fighters, though its accuracy leaves something to be desired. In Afghanistan, the AK-47 is ubiquitous, and every one has a story. And while journalists don’t carry weapons, they have stories too. Here are mine.

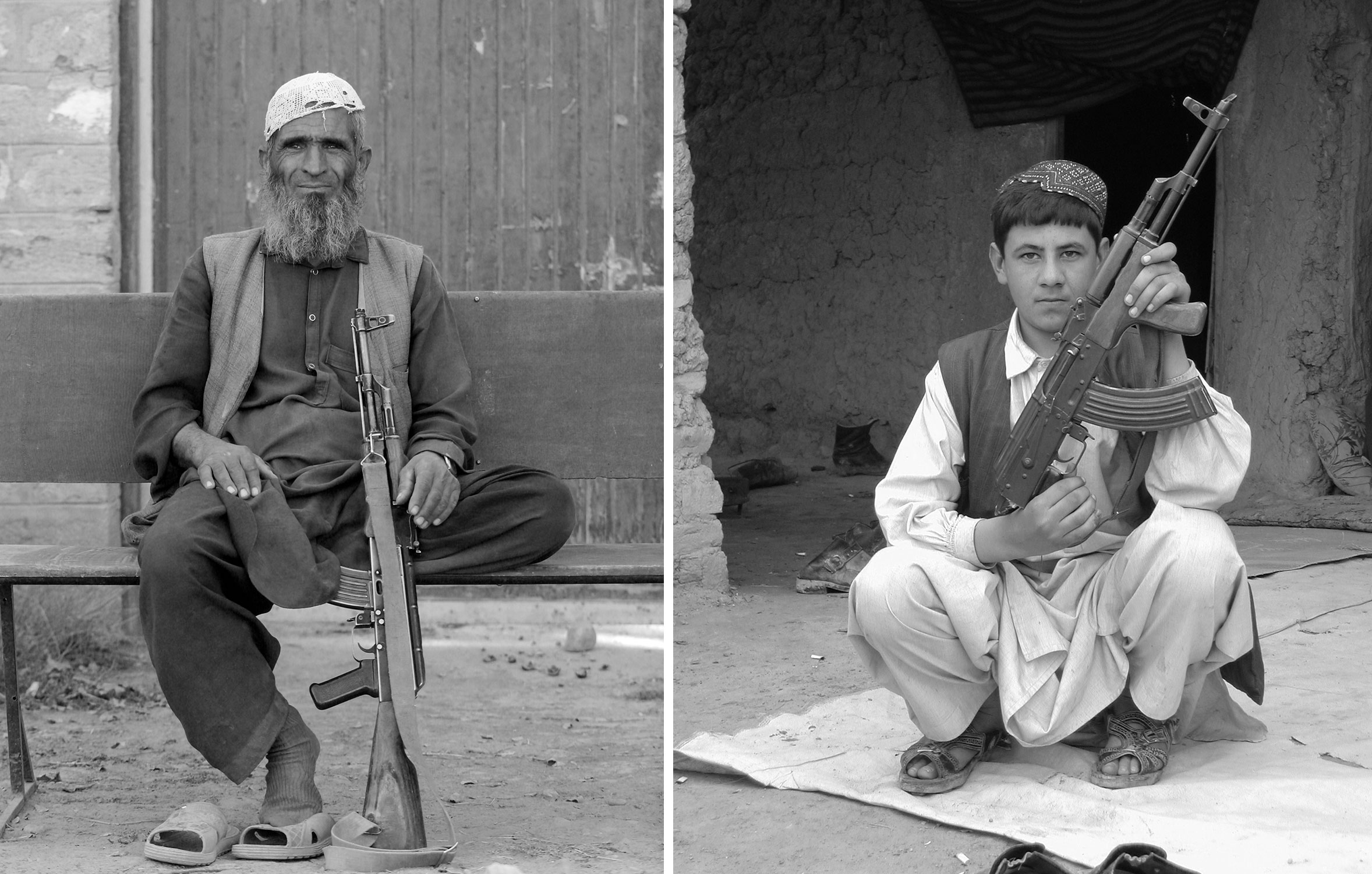

In 2002, I had a walled compound of my own in Kandahar, with a fixer/driver, a cook, a “sweeper,” and two Mujahedeen guards, Syed and Abdul. Their uncle came along to vouch for them my first night. Syed was a former Taliban bookkeeper; Abdul had been tossing molotov cocktails at Russian tanks when he was 13. This was Abdul’s AK. I came to know it well.

Abdul and I formed a bond over his weapon. He couldn’t speak a word of English but he sat me down that first night and taught me how to take apart and reassemble his AK-47. After that, Abdul was always at my side. In the evenings, the whole group would sit around and watch as I sat at a card table in the middle of the courtyard writing stories and editing pictures, then filing them to Toronto by satellite. Gradually, each one would wander off to bed. Not Abdul. He would fall asleep in his chair next to me, a blanket wrapped around him and his AK leaning against my chair. It was always unnervingly pointed directly at my head. I would pick it up and check the safety. Unfailingly, it was on full-automatic. I’d switch it to Safety.

One of the reasons the AK is so popular is that it’s an uncomplicated weapon and dead simple to copy. Most of the AKs in Afghanistan were made right next door in China.

Everyone, it seemed, had an AK. Young, old—it didn’t matter. It was the weapon of choice for good guys and bad.

This militia fighter rode up out of nowhere during a desert patrol. There is an element of the Wild West to Afghanistan. But instead of Winchesters and Colts, the “cowboys” carry AKs.

AKs were so common in the hands of ordinary people, militia and patrolmen like this young officer, you hardly noticed them after a while. They were as common a tool as a pick and shovel, all over Afghanistan.

In 2014, Kathy Gannon, an Associated Press journalist from Timmins, Ont., was shot twice by an AK-wielding Afghan police officer who opened fire on her car outside the city of Khost, Afghanistan. Gannon survived, but her colleague and close friend, AP photographer Anja Niedringhaus, 48, of Germany, was killed. The pair were with election workers delivering ballots under the protection of the Afghan National Army and Afghan police.

An Afghan National Police officer leads a Canadian jeep from 3rd Battalion, Royal 22nd Regiment, on a joint Canadian-Afghan patrol through a neighbourhood in Kabul on Sunday, May 30, 2004. More than 100 Canadian troops and dozens of Afghan police set out to discourage crime. But low salaries and corruption at the highest levels often meant Afghan police themselves exploited the populace. In many cases, they were more feared than respected.

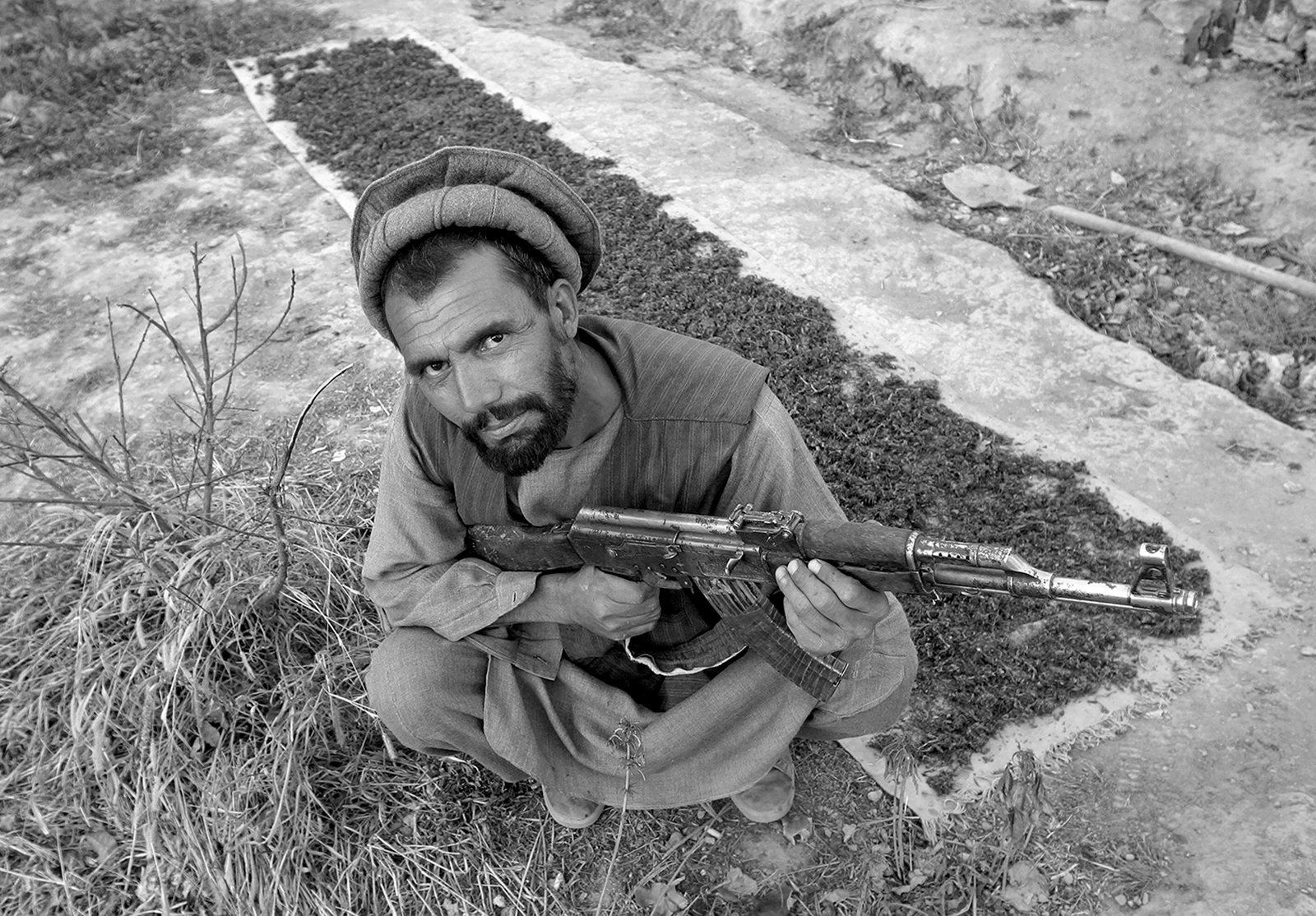

This guy was known as Osama, a common name in Afghanistan. He was a militia fighter commanding an isolated checkpoint deep in the mountains southwest of Kabul. There were lots of weapons casually lying around—AKs, rocket-propelled grenades and launchers; other stuff. And drugs, lots of drugs, including his stash of dope, here drying in the sun. He was high—on opium, it appeared. I shot 96 pictures of him in and around the adobe hut that he shared with another militiaman. On the 96th picture, he raised that AK to my head. He’d had enough pictures. Three Canadian soldiers were right there with their weapons drawn, and he lowered his. But I had my photo.

Master Corporal Jamie Lewis of London, Ont., helps a blindfolded Afghan National Army soldier take apart his AK-47 assault rifle at the presidential palace in Kabul on Wednesday, Oct. 29, 2003. Twenty members of 3rd Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment, were the first Canadians seconded by the U.S.-led Operation Enduring Freedom to train Afghan soldiers.

Sgt. Dave Dunn, a paratrooper from Big River, Sask., watches as an Afghan National Army recruit takes apart his AK during training at the presidential palace in Kabul.

Monitored by a Canadian trainer, Afghan National Army troops disassemble and assemble their AK-47s at the presidential palace in Kabul.

‘This is my rifle; this is my gun….” Like soldiers the world over, an ANA recruit comes to know his weapon intimately. ANA troops numbered just 1,750 in early 2003. They would grow to 194,000 by the time Canada shut down its Afghanistan operations in 2014. Salaries averaged about US$30 a month. Maintaining the ranks during non-fighting seasons (fall/winter) has always been a challenge.

An AK hangs from the back of an Afghan National Army recruit in 2003.

Grabbing a power nap in the middle of a training day at the presidential palace in Kabul.

Advertisement