Margaret Bourke-White’s photograph of the aftermath of the bombing of Leipzig. [Margaret Bourke-White/Life Magazine]

Armed with a bulky 4×5 box camera, the lieutenant from London, England, captured striking images of Canadian soldiers in the trenches and among the ruins of First World War Europe. The locales, the faces and the circumstances humanize the history behind the photographs, bringing it to life as few did.

A press photographer who joined the Daily Mirror in 1910, Rider-Rider took the torch passed to him by Crimean War photographer Richard Fenton and the U.S. Civil War’s Mathew Brady before him, and carried it forward to a new generation that would emerge during the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War.

His most recognizable image remains a national icon more than a century after it was taken: Canadian ace Billy Bishop, a resolute grin on his face, casting an over-the-shoulder glance from the cockpit of his Nieuport 17.

Canadian ace Billy Bishop in the cockpit of his Nieuport 17 in August 1917. He had 37 kills to his credit and had earned a Victoria Cross when this photograph was taken. [WILLIAM RIDER-RIDER/LAC/PA-001654]

There are others among Rider-Rider’s priceless archive: Canadian soldiers entering the ruins of Cambrai in the final weeks of the war, casually making their way along a littered street as if out for a Sunday stroll, seemingly oblivious to the camera; a tableau of stoic German prisoners, some bandaged, in September 1918 waiting to be processed; troops carrying wounded through the mud at Passchendaele in 1917.

“Passchendaele was a treacherous place for a cameraman—or anybody else, for that matter,” Rider-Rider wrote in a magazine of the day called Canada in Khaki.

“Always one had to pick one’s way through deep shell holes filled with murky slime; no trenches worthy of the name and only short tracks of duck boards which were continually under shell fire.”

German prisoners taken by the 4th Canadian Division during its crossing of the Canal du Nord on Sept. 27, 1918. The picture was taken near Inchy, just behind the Canadian sector of the front, to the west of the canal. [William Rider-Rider/IWM-CO3302]

A plethora of news-picture magazines emerged between the wars—Life in 1936, Look in 1937, Picture Post in 1938, and many more. The genre was hugely popular long before television, the Internet and handheld devices gave the masses fingertip access to real-time images, video and stories from around world.

The most successful of them was the weekly Life, its staff a who’s who of groundbreaking cameramen and women, including the legendary Robert Capa, W. Eugene Smith—the “father of the photo essay”—and Margaret Bourke-White, who shot the magazine’s first cover, a massive dam project in Fort Peck, Montana.

This era of photography was aided by advances in press printing technology, paper quality and photographic equipment—namely, the compact 35-millimetre camera, some with interchangeable lenses, and accompanying film.

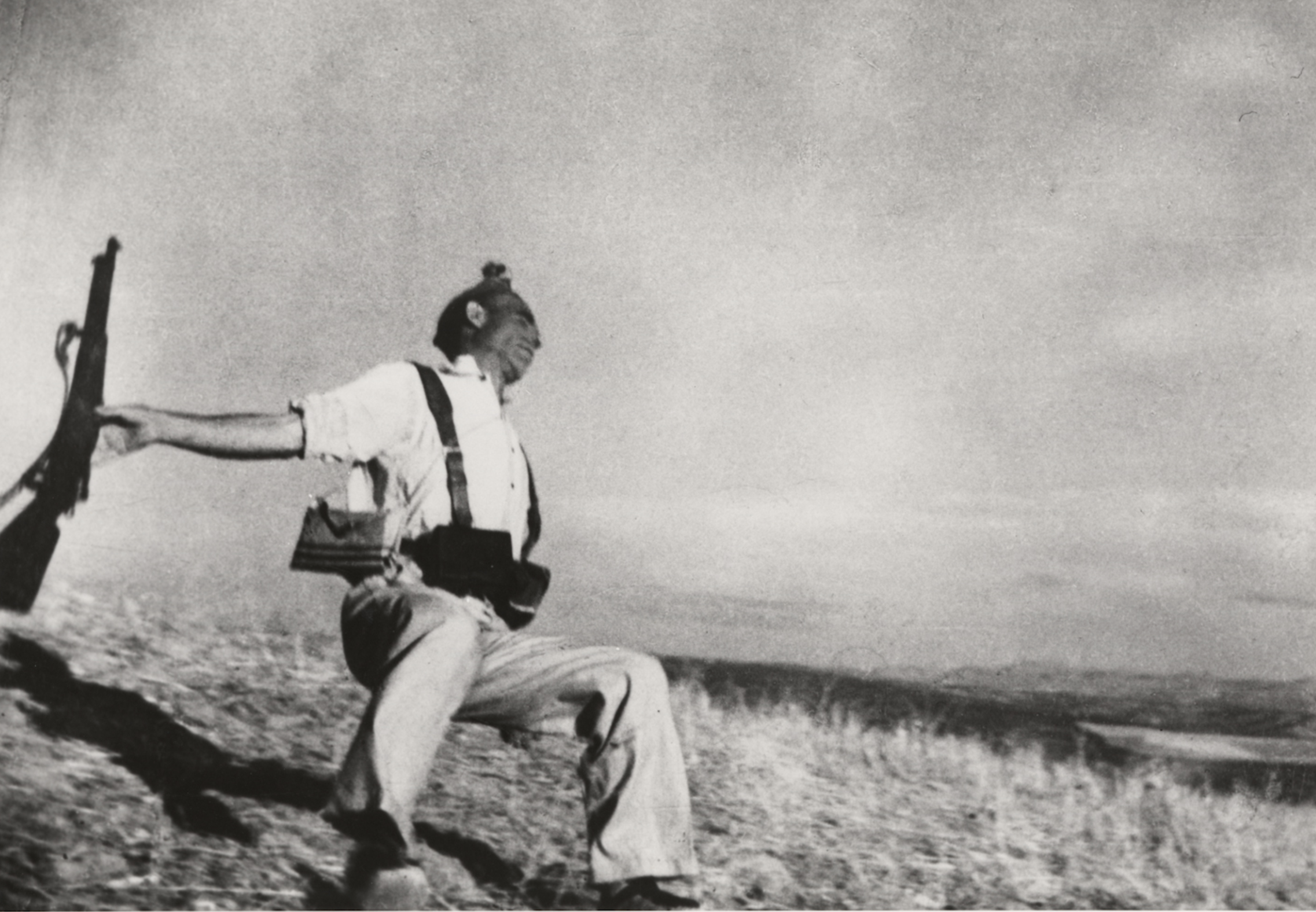

Robert Capa’s Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death. [Robert Capa/ICP]

French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson advanced his philosophy of capturing “the decisive moment” in the early 1930s using 35-millimetre film in the streets and salons of Paris. He would go on to become one of the Second World War’s most celebrated photographers, his pictures packed with emotion.

Capa first took his Leicas to Spain, from which the veracity of his photograph of a falling soldier, entitled Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death—taken long before Photoshop’s unchecked digital manipulations caused a veritable industry crisis—is argued to this day.

It was Capa who said, “if your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough.” The cameras, lenses, film and access gave photographers of the day unprecedented photographs of soldiers in battle and civilians in turmoil, a special talent of Cartier-Bresson.

Bourke-White documented women working in factories on the home front, U.S. soldiers in combat, and emaciated death camp prisoners upon their liberation.

Her photograph of the aftermath of the bombing of Leipzig—a withered hand reaching from the rubble alongside a typewriter, the name “Triumph” emblazoned across its paper table—is among the most impactful images of a war brimming with unforgettable photographs.

Bourke-White was not the only woman who notably wielded a camera in the 1939-45 period.

Lee Miller in Hitler’s Munich apartment on April 30, 1945, after she photographed the Dachau death camp. [David E. Scherman/Courtesy Lee Miller Archives]

“She loved it at first,” her son, Antony Penrose, told the London Telegraph in 2016, “but quickly became bored, seeing it as vacuous and shallow.

“Modelling is a profession with a very high casualty rate—Lee survived because she morphed into becoming a photographer.”

She travelled to Paris and persuaded surrealist Man Ray to teach her photography. She became his lover, muse and collaborator, befriending many of the city’s notable artists in the process.

Years after their relationship ended, she reinvented herself as a photojournalist, documenting the London Blitz. After America entered the war in 1942, Miller became a war correspondent for Vogue, attaching herself to the U.S. Army’s 83rd Infantry Division.

She was in the front line of the Allied advance from Normandy to Paris, and on into Germany.

“The GIs liked her—they saw her as a good buddy,” Penrose said. “She could swear as well as they could and put up with being under fire.”

On April 29, 1945, she entered Dachau as it was liberated by American forces. Shocked, she photographed the evidence of the Nazis’ extermination of the Jews and others.

“The pictures are stark and sickening, and have lost none of their emotional impact,” the Telegraph reported.

Later that same day, she accompanied the GIs into Munich, where they discovered Hitler’s apartment. Miller set up a photograph of herself naked in Hitler’s bath. Given the circumstances, it was a striking image.

“I think she was sticking two fingers up at Hitler,” said Penrose. “On the floor are her boots, covered with the filth of Dachau, which she has trodden all over Hitler’s bathroom floor. She is saying she is the victor. But what she didn’t know was that a few hours later in Berlin, Hitler and Eva Braun would kill themselves in his bunker.”

Miller would later marry and give birth to her son, but the horrors she had witnessed changed her life. She became an alcoholic and fell into clinical depression. Penrose believes she suffered from what became recognized as post-traumatic stress disorder.

“It’s not easy to have a relationship with an alcoholic parent,” Penrose told the newspaper. “It was challenging, unusual and threatening. She was normally a very generous, sensitive and kind person, but when drunk she would be verbally abusive and cutting. The things she’d say would be really astonishing. She never hit me—she didn’t need to. She could do all the damage with words.”

Now 72, Penrose grew up unaware of his mother’s work. It wasn’t until after she died in 1977 that some 60,000 of Miller’s prints, negatives and articles for Vogue were discovered in the attic of the family’s East Sussex home.

The revelation transformed his view of his mother and he has since been devoted to celebrating her achievements.

A wounded marine is carried off by his comrades during the Vietnam War’s Tet Offensive in 1968. [Don McCullin/Contact Press Images]

His discussions with Marines in the Battle of Chosin Reservoir were as noteworthy as his photographs: “I asked him, ‘If I were God, what would you want for Christmas?’ He just looked up into the sky and said, ‘Give me tomorrow.’”

Duncan went on to produce more great work in Vietnam, notably during the siege of the American base at Khe Sanh. It was probably the most photographed war in history and ushered a new age of saturated coverage that found its way into North American living rooms virtually on a nightly basis for more than a decade.

The Vietnam War turned out a long line of great photojournalists, including Larry Burrows, Don McCullin, Tim Page, Dana Stone, Henri Huet, Eddie Adams, Dicky Chappelle, Nick Ut, Catherine Leroy, Phillip Jones Griffiths, Horst Faas, David Hume Kennerly, and Erroll Flynn’s son Sean.

In a war where journalists and photojournalists hopped helicopters in and out of battle like taxicabs, many died, including Burrows, Stone and Flynn.

Two photographs were widely recognized as helping set American public opinion against the war: Adams’s 1968 “Saigon Street Execution” and Ut’s “The Terror of War,” which depicted a naked and badly burned Phan Thi Kim Phúc, age 9, running from a napalm strike in 1972.In both cases, the issue of whether to transmit the photographs was hotly debated in Associated Press newsrooms.

“An editor at the AP rejected the photo of Kim Phúc running down the road without clothing because it showed frontal nudity,” said Ut, now an American citizen living in Los Angeles. “Pictures of nudes of all ages and sexes, and especially frontal views, were an absolute no-no at the Associated Press in 1972.

“Horst [Faas] argued by telex with the New York head office that an exception must be made, with the compromise that no close-up of the girl Kim Phuc alone would be transmitted. The New York photo editor, Hal Buell, agreed that the news value of the photograph overrode any reservations about nudity.”

Both photographs fronted newspapers around the world, with Adams’s execution photo topping the front page of the New York Times and, four years later, Ut’s naked girl appearing below the fold.

Kim Phúc came to Canada in 1992 and lives outside Toronto.

“Forgiveness made me free from hatred,” she told U.S. National Public Radio in 2008. “I still have many scars on my body and severe pain most days, but my heart is cleansed.

“Napalm is very powerful, but faith, forgiveness and love are much more powerful. We would not have war at all if everyone could learn how to live with true love, hope and forgiveness. If that little girl in the picture can do it, ask yourself: Can you?”

Phan Thi Kim Phúc, who was pictured at age 9 running from a napalm strike in Vietnam in 1972, has lived in Canada since 1992. [Joe McNally/Life Magazine]

There have been instances of Photoshop manipulation, not unlike early day composites and staged photographs, but the old rules of truth in storytelling have prevailed, despite the cries of “fake news.”

After Vietnam, a new generation of war photographers emerged to chronicle disparate strife in Africa, Latin America, Eastern Europe and the Middle East—the likes of James Nachtwey, along with Lynsey Addario, and the late Tim Heatherington and Anja Niedringhaus.

Capa’s old maxim held up, expressed so eloquently by the man many consider the greatest photojournalist of the past half century, Briton Don McCullin.

“I don’t believe you can see what’s beyond the edge unless you put your head over it,” McCullin said. “I’ve many times been right up to the precipice, not even a foot or an inch away. That’s the only place to be if you’re going to see and show what suffering really means.”

Advertisement