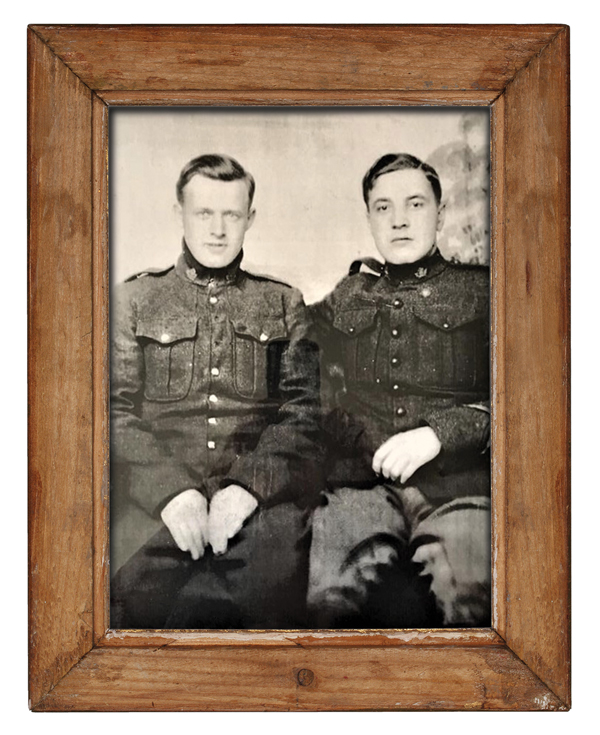

Hormidas Odilon (Henry) Goulet enlisted with the 22nd Battalion in Montreal in 1914. When he gave his name, the officer apparently told him, “We’ll call you Henry.” He fought in France and Belgium until he was wounded in 1916. He was discharged in 1917. His journal was recently adapted into this memoir by his granddaughter Michelle T. Lambert.

Henry Goulet (right) and Ephrem Tremblay were friends who travelled together from Biggar, Sask., to Montreal to enlist with the 22nd Battalion. [Courtesy of Michelle T. Lambert]

It’s 1914. I’m fed up with the farm and doin’ my own cookin’. No steady girlfriend. An ol’ man tells me about the war. It can’t last very long, he says. Canadian government’s recruitin’.

I talk to my good friend Ephrem Tremblay and we go to Saskatoon to enlist. Be back by spring, we think. They turn us down. “More applications than we need but you’re French Canadians. Go to Montreal. They’re forming a French-Canadian battalion.”

We hitch back home just south of Biggar, Sask. Ephrem sells some wheat and I sell some cattle. Enough for train tickets and some beer. The fare’s $50.50. We load a suitcase full of groceries, and head for the Grand Trunk Railway to Winnipeg. Then we travel through the States to Chicago, then back up to the Dominion of Canada, then up to Quebec. In Montreal, we join the 22nd Battalion (French Canadian) of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. It’s Nov. 2, 1914.

We get taken to Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, not too far southeast of Montreal, where we train all winter. Pay’s a dollar ’n’ ten cents a day, with food, laundry and clothing included. We’re in a big building in Saint-Jean with three boards to sleep on, ’bout six inches off the floor. I overhear fellows who’ve served jail time: army or jail. What a choice.

Soon I realize I have to take orders. Trainin’s hard and food is bad, but it’s not the government’s fault. I heard the major’s pocketing food money. Bread and soup. We go to the little town at night, where whisky’s five cents a glass; beans or macaroni, same price.

In the spring of 1915, we’re off to Amherst, N.S., then to Halifax, where we guard prisoners. Come May 20, about 2,000 of us get aboard a troopship, the SS Saxonia, bound for England. More training.

It sure is a pretty coastline with the flowers. I’ve never seen so many nice flowers. Since I speak English, I take courses for lineman. Then comes the call for active service. On Sept. 15, 1915, we board a boat at Dover and ship out to France. Standing room only for five hours: protection against the submarines, we’re told. I wish I was back on the homestead.

Medics tend to the wounded in a trench near Courcelette, France, during the Battle of Flers-Courcelette in September 1916. Goulet was wounded in the battle. [William Ivor Castle/DND/LAC/PA-000627]

We disembark at the major port of Calais in northern France, where we end up in the trenches. We fight as part of the 5th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Division, in France. Bad weather. Have to sleep in the mud.

Ephrem, my best friend, is killed today, Oct. 2, 1915. He’s on top of a trench, putting down sandbags. German sniper gets him. He was 10 years older than I, and like a father to me. He watched over me.

In July 1916, I am sent to the front line near Ypres in Belgium. Bloody attacks and so many rats. Heavy Canadian casualties.

In early September, I am in Ypres and then St. Eloi, France, detailed for a bayonet charge. They tell us to take a crater between our trench and the German one. Lose several men. So much rain. Trench feet. Have to bury four men under me one night. One of the guys finds a deep well. We fill it up with dead soldiers.

I receive very few letters in the Army. Others get parcels with letters. My family’s very poor and my sisters have big families. I never get a parcel.

I transfer elsewhere in Belgium, assigned to care for Major Georges P. Vanier’s horse. Battle’s fierce. British launch a massive offensive. Come with 50 big tanks going over trenches, through barbed wire. Tons of planes over our heads and so much heavy artillery. My hearing’s getting bad. Bombs are dropping down on us. Heavy losses. A third of British troops killed. There are corpses all over, wounded asking for help. Regiments of 900 to 1,000, with only 100 left. Soldiers shell-shocked, others praying out loud. This is hell.

We capture the village of Courcelette in northern France. It’s Sept. 15, 1916. Four of us get into a shell hole. Then a shell explodes behind us. Two officers killed. A private is wounded, then makes the mistake of getting up. He’s shot right away. Can’t even begin to count the number of wounded. I wish I was back on the homestead.

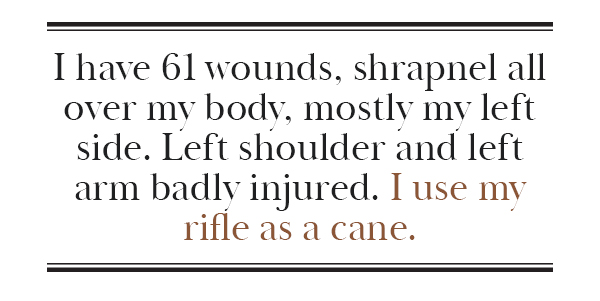

I have 61 wounds, shrapnel all over my body, mostly my left side. Left shoulder and left arm badly injured. I use my rifle as a cane. Fall into a hole ’til an ol’ Scot messenger gets me out. Blood chills my body. First, I’m hot, then I’m cold. Am I dying, am I not?

Now I wake up in a sweat, thinkin’ ’bout the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, burying soldiers, and my friend dyin’ beside me.

They load every couple of men onto two-wheeled carts pushed by four soldiers. We’re bandaged up and given a cigarette. Hoist us up on trucks; strap us on so we can’t fall off. It’s a rough ride as the driver has to dodge shell holes. All we do is curse.

Finally, they get us to a field hospital in a tent north of the Somme River between Arras and Albert. Snow! The Somme offensive grinds to a halt on Nov. 18, 1916, after five long months of fighting.

Some are sent to a hospital in France. Next day, I’m on a stretcher in a boat bound for England. Brought to London to a hospital in Richmond Park. The British Medical Corps is there. I’m the only non-Brit. They call me colonial.

A medical case sheet from Goulet’s file details the multiple shrapnel wounds he suffered. [LAC]

My wounds take a long time to heal and my arm is stiff. Nurse gives me massages. Doc tells me to exercise my arm, but I don’t do it ’cause I don’t wanna go back to the trenches. They send me to a convalescent home. Nice place with good food and lots of entertainment.

After a few weeks, they send me to the village of Sandgate, near Folkestone in Kent. There I get light duty, serving coffee. At least I’m not in the trenches. Back of the building faces the sea, so I go and stretch out on the sand. Meet a nice girl with red hair. I think she’d marry me, but I can’t see how she’d fit in on a homestead back home.

The Canadian public back home is raising a fuss ’bout the Army keeping so many cripples in England, and having to send too much food over here. Meanwhile, German subs are still very active.

Another medical. Many in the line-up get sent back to France. Others get six months of light duty, then back to the trenches with, “Best o’ luck, mate.” My turn, and it’s “Canada for you.” I’m so excited! I can hardly wait to get back on the homestead!

A few days later, I’m on a boat going back to Canada. We’re only 15 on this one. Several days on the coast of Ireland, have to wait till it’s safe to travel.

A plaque recognizing Goulet’s service was presented to him in July 1919. [Courtesy of Michelle T. Lambert]

Land in Quebec City. There I pretend I can’t speak French and have lots of fun with the waitresses. Because I got wounded in the left shoulder, ’course it doesn’t show. On the train a lady remarks, “The good boys don’t come back, but the bad ones do.” I tell her “I’m one of the bad ones, been there since 1914.” I’ve been gone a long, long time.

A bunch of us get sent to Moose Jaw, Sask. We’re treated like heroes! It’s good to be back on Canadian soil, but it’s still hard to sleep. Now I wake up in a sweat, thinkin’ ’bout the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, burying soldiers, and my friend dyin’ beside me.

They tell us we can take some courses. I’m in a hurry to get the uniform off and see my home again. Meet the main doctor and tell him about my farm, that I wish I was back on the homestead. Finally, the good doc speaks: “You’re welcome to stay until spring. But if you want a discharge, you’ll get it soon.” He arranges for a medical and recommends a small government pension.

Finally, I’m back home on my homestead. My little pension takes a very long time in getting to me from Ottawa. My shoulder’s hurtin’ and I can’t stop thinkin’. Finally fall asleep. I wake up in a sweat, thinkin’ ’bout the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, burying soldiers, and my friend dying beside me.

Epilogue: Hormidas Odilon (Henry) Goulet—my pépère [grandfather]—was devoted to The Royal Canadian Legion until his death in 1978. He regularly went to the branch, where he would talk with his old chums, support its causes, and always spoke highly of it. Every year on Remembrance Day, rain or shine, no matter the weather, he would go to the cenotaph, dressed in his army uniform. He would never say anything about where he was going or why.

Advertisement