John Stewart Hart, Canada’s last living Battle of Britain pilot, at his home on his 100th birthday, Sept. 11, 2016. [RCAF]

Ask Canada’s last-surviving Battle of Britain veteran which aircraft he preferred, the Supermarine Spitfire or the North American P-51 Mustang, and the 102-year-old fighter pilot doesn’t bat an eye.

“The Spitfire every time,” says John Stewart Hart, a Second World War squadron leader who flew both, as well as Hurricanes, during six years of combat. “The Spitfire was more responsive, easier to handle. They made you feel like you were one with the machine. You moved and the machine moved. It was a by-reflex sort of thing. Beautiful looking and beautiful to fly.”

A dentist’s son from Sackville, N.B., Hart was one of Churchill’s “Few,” a pilot in No. 602 (City of Glasgow) Squadron, Royal Air Force. Flying as many as two sorties a day through the summer and fall of 1940, he shot down two Messerschmitt Bf-109s and a Junkers Ju 88, confirmed, along with another probable Ju 88.

Based at Westhampnett, near the famed RAF Tangmere air base in England’s southeast corner, then-Flying Officer Hart took his share of fire too, pressing attacks to within 50 metres or less—so close he could see the faces of his enemy. Yet, while his plane was heavily damaged several times and set ablaze once, he was never shot down.

Just 112 Canadians fought alongside 2,353 British and 462 other pilots in the skies over Britain and the English Channel during those few critical months after Hitler had overrun Europe. The Nazi Führer had set his sights on the British Isles; Prime Minister Winston Churchill vowed England would “never surrender.”

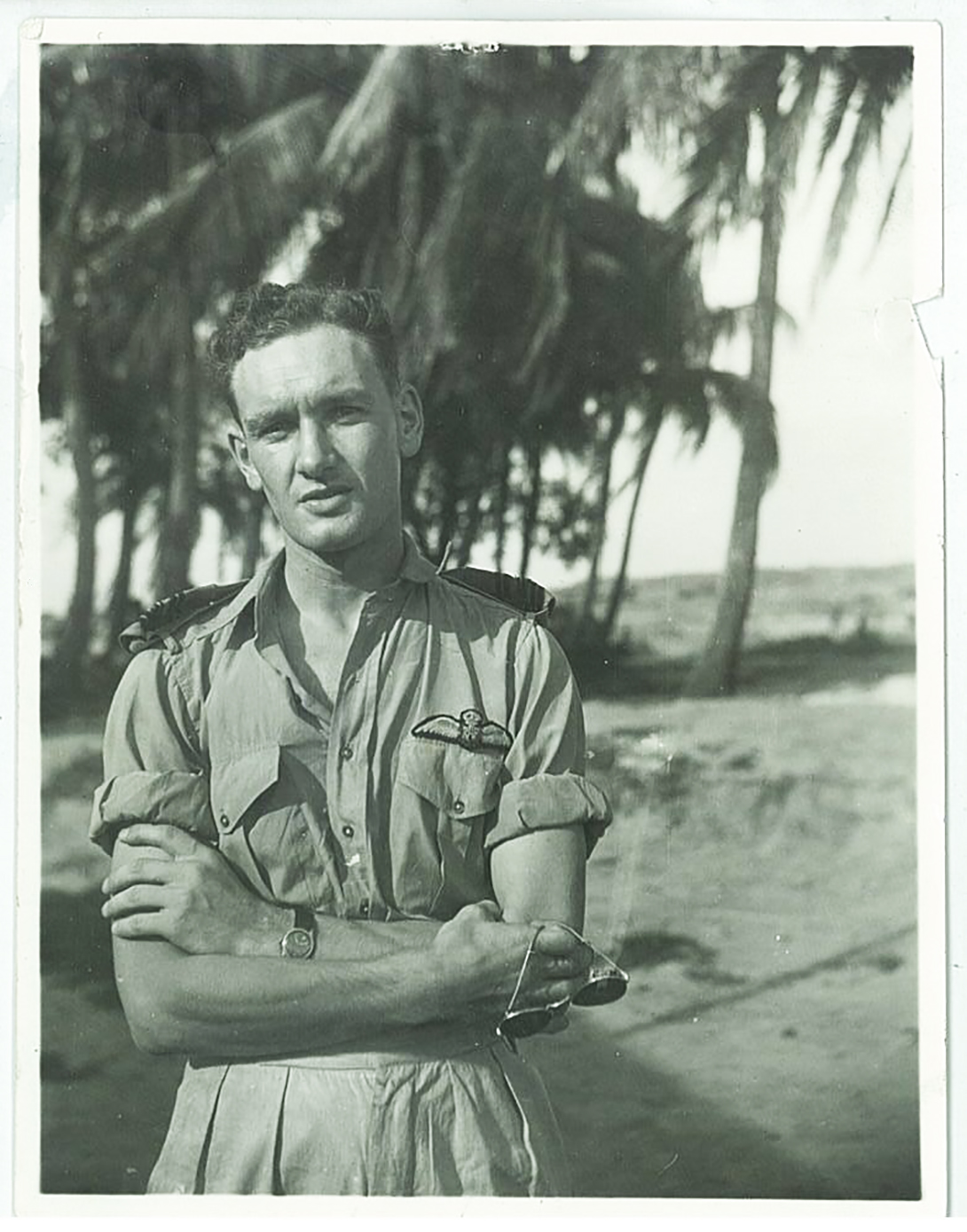

John Stewart Hart in tropical kit while commanding No. 67 Squadron, RAF, in India during the Second World War. [Courtesy Hart family]

Now living in Naramata, B.C., after a career in Vancouver real estate (he retired in 1976), Hart is the last of The Few from Canada and has been since June 25, 2016, when Montreal-born Squadron Leader Percy Beake died in Bath, England.

Hart is also one of the rare few who went up against both German Messerschmitts and Japanese Zeroes, which he faced while flying Hurricanes in India and Burma.

He quit the engineering program at Mount Allison University and learned to fly in a Tiger Moth at the Halifax Flying Club in Nova Scotia, then went to England in 1938 as the winds of war began to stir.

A private pilot’s licence in hand, he joined the RAF on a short service commission, arriving at No. 7 Operational Training Unit in England in January 1939. He finished his air force training on North American Harvards. They “handled like a logging truck,” he scoffed.

“War was declared just about the time we graduated from training,” he said. The whole class of about 20 was assigned immediately.

He was 24, older than many of his colleagues, when he began flying Westland Lysanders, a brutish-looking aircraft whose short take-off and landing abilities later made it an ideal delivery vehicle to land spies and supply French Resistance fighters on improvised landing strips in secluded meadows and fields of occupied France, usually at night. But in late 1939 and early 1940, Hart was flying coastal patrols, looking out for an invasion.

Following the evacuation of Allied forces at Dunkirk in June 1940, he was transferred to fighters, training on the Spitfire for just a week before he was activated. He was eventually assigned the Mark II of what would become 24 versions of the legendary aircraft known for its elliptical wings and flawless lines. Its three-bladed prop was a signature element of Battle of Britain Spitfires.

Hart didn’t see action right away. The ranks of his newest squadron, No. 602, were already so ravaged by the fighting that it stood down briefly to reconstitute. The Luftwaffe had the upper hand early in the battle, directing its attacks on airfields while the British scrambled to ramp up aircraft production and pilot training.

In fact, the reason he says a Canadian was brought to the squadron at all was because “they had lost quite a few and had to replace them with outsiders.”

Polish, Canadian, Czech, Australian, New Zealander and other pilots joined the fray. Most of the Canadians served in No. 1 Squadron, RCAF, later to become 401. Eighteen months before Pearl Harbor, American pilots, many Canadian-trained, joined the RAF. As the trickle became a tide, they would eventually form the Eagle Squadrons—three RAF fighter units made up entirely of American volunteers.

At the battle’s outbreak, the Luftwaffe in Belgium and northwestern France had 700 to 800 Bf-109s, 1,000 to 1,200 bombers, just over 200 twin-engined fighters and just under 300 dive bombers—about 2,500 aircraft, in all. On July 7, Fighter Command had 644 available fighters and 1,259 pilots.The average life expectancy of a Spitfire pilot during the Battle of Britain was four weeks. The fate of the free world hung in the balance, yet the desperation of those times was not something Hart says he and his fellow pilots dwelled upon. They were focused on the task at hand.

“We knew it was getting pretty tough, but I don’t think we realized how close it was.”

Another 602 pilot, George Pinkerton—a rhubarb farmer from Hogganfield on the outskirts of Glasgow—had fired the first shots of the air war over Britain months earlier, intercepting a Heinkel 111 on Oct. 16, 1939, before bringing down a Ju 88 off Crail on the Scottish coast later the same day.

The grass field at Westhampnett was on the front line of the Battle of Britain. The squadron had been thrust into the thick of the action, serving at the front longer than any other during the battle and achieving the second-highest number of aerial victories, according to its website.

“Group Commander sends warmest congratulations to 602 Squadron on their magnificent combat at midday when they destroyed eight fighters and shot down two others without loss of pilots or aircraft creating a record for months past,” said a message from HQ 11 Group after the Luftwaffe’s last major daylight assault on Britain on Oct. 29, 1940.

Hart flew once or twice a day—less, he said, than some pilots he knew who flew three to four times daily, sometimes more, during many of the 114 days the battle raged. It took 26 minutes to rearm and refuel a Spitfire, triple what it took a Hurricane. Sorties averaged between 60 and 90 minutes.

His encounters with the enemy were fleeting and furious—“short-lived,” was how he described his kills. The Mark IIa Spitfire had a level top speed of 575 kilometres an hour; the Messerschmitt Bf-109e (also known as the Me-109) came in at 570.

The speed advantage tended to shift back and forth with each new aircraft version, and there were many. The point is, both were fast and encounters were brief. But there were ways that pilots could eke out an advantage.

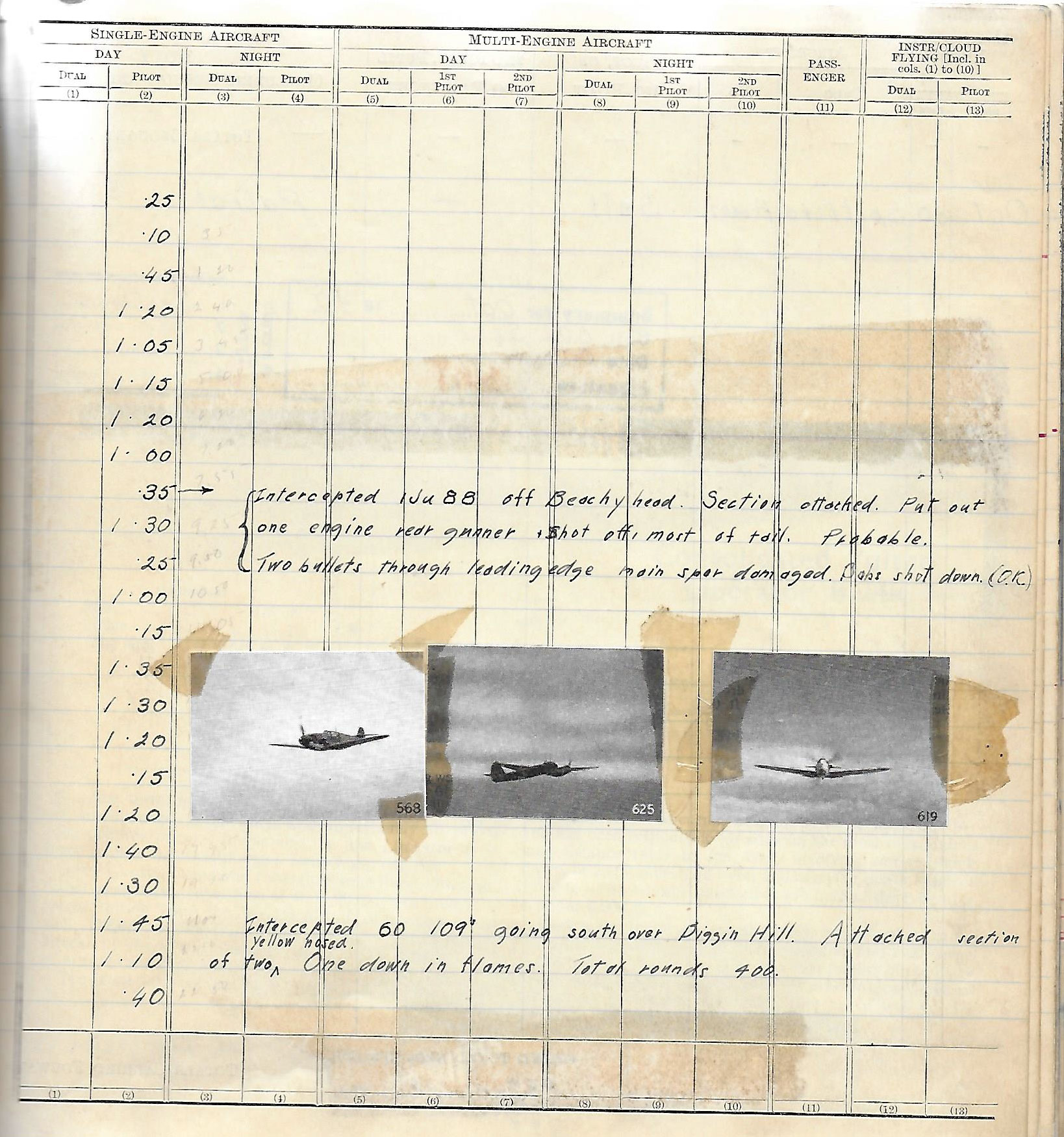

A page from Hart’s Battle of Britain logbook. The gun-camera images are taped inside for identification purposes. [Courtesy Hart family]

“We knew it was a pretty equal battle,” said Hart. “The 109 was sometimes better, sometimes not quite as good. It depended on the mark and which mark we were flying.”

In the Spitfire Mark II, 2,400 rounds fed eight Browning .303 machine guns, each capable of firing at a rate of 1,150 rounds per minute. That’s 15 seconds of total firing time. Attacking pilots would normally deliver two-second bursts.

Hart could recall no protracted dogfights, but he said he often returned from sorties with empty ammunition bays, “or close to it.” There was at least one notable exception recorded in his logbook, the date unclear.

“Intercepted 60 109s going south over Biggin Hill,” he wrote. “Attacked section of two yellow nosed. One down in flames. Total rounds 400.”

That’s 2.5 seconds of shooting. “Good aim,” he acknowledged, 78 years later.

He taped gun-camera still photos of a Ju 88 and two Messerschmitts in his logbook for identification purposes, including one of a 109 coming head-on.

Hart’s close calls were too numerous to count. Once, a Ju 88 gunner holed his radiator at 20,000 feet and he barely made it back.

“It was off Southampton, about 20 miles [32 kilometres] out over the Channel,” he said. “I wasn’t aware I was hit until glycol [antifreeze] started burning over my [exhaust] stubs. It was blazing. I shut down the engine and headed for home. I landed right at my home base, at Westhampnett.”

His wing was damaged in another attack.

“Intercepted 1 Ju 88 off Beachyhead,” his logbook notes. “Section Attacked. Put out 1 engine rear gunner + shot off most of tail. Probable.

“Two bullets through leading edge main spar damaged. Babs shot down. (O.K.)”

The mission lasted an eventful 35 minutes.

Hart’s was among 12 Spitfires that set out to intercept another force of 60 Messerschmitts.

“They found us before we found them,” he said. “They were high above us and they went right through us. We hadn’t reached our full height when they attacked. They kept going; they didn’t come back. Not a soul” was lost.

The Messerschmitt pilots, many of whom had fought in the Spanish Civil War and through the European blitzkrieg, were generally more experienced than their Allied foes. Some would go on to rack up hundreds of kills, the bulk of them on the Eastern Front. Battle of Britain ace Gerhard Barkhorn, No. 2 on the Second World War scoring list, would record a total of 301 victories; No. 3 Günther Rall had 275 by war’s end.

“Some [German pilots] were aggressive and some were not,” said Hart. “But it came down to a bit more horsepower, maybe a refinement somewhere.”

His own piloting skills, he said, “were enough to survive.”

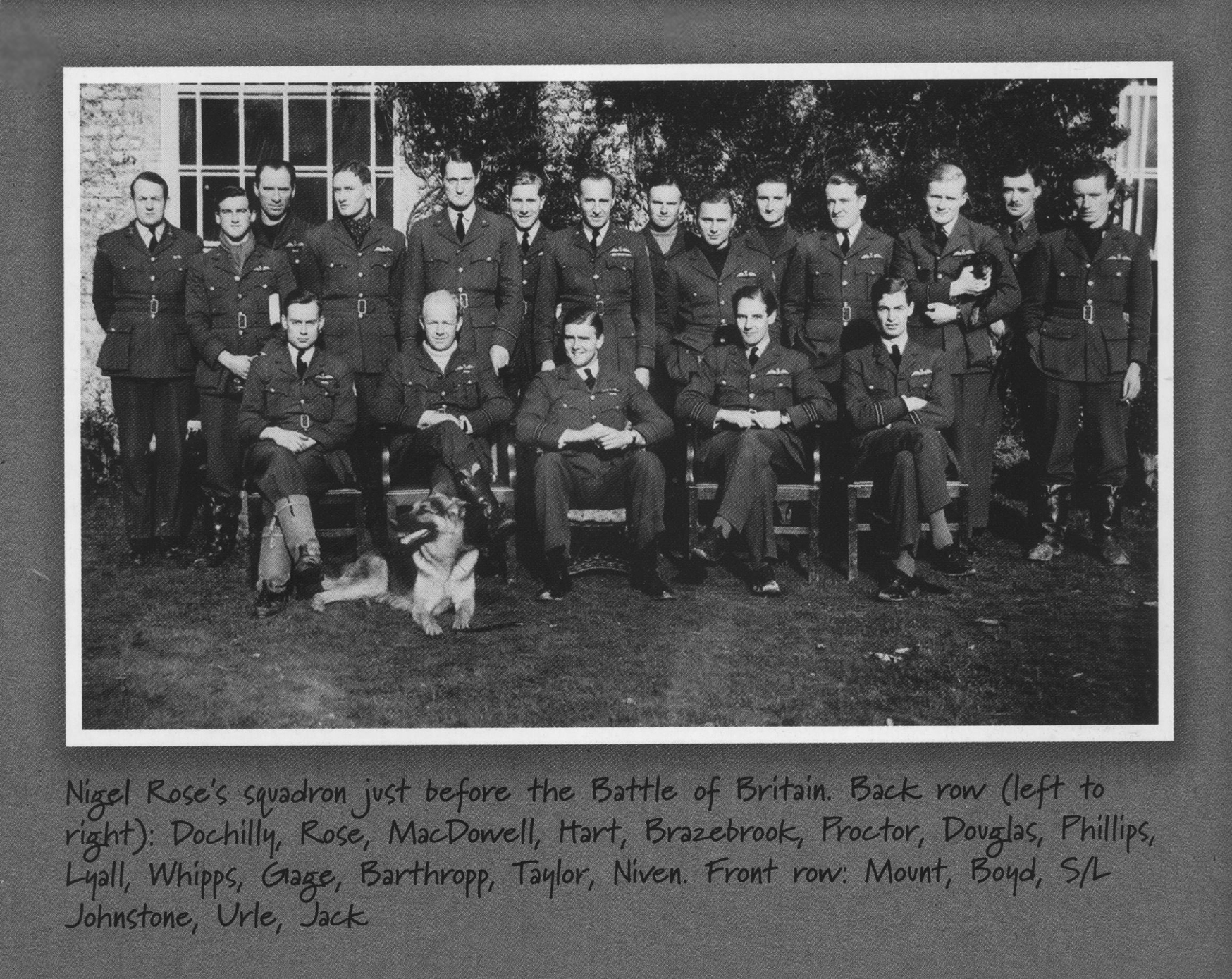

Hart, third from right, with 602 Squadron mates at Westhampnett during the Battle of Britain. [Courtesy Hart family]

A redhead whose father George was president of Mount Allison University from 1923 to 1945, Flying Officer Trueman left Sackville for England ahead of Hart—a contributing factor in his own decision to go, Hart said.

Almost 3,000 aircraft were downed during the battle—1,023 Allied and 1,887 Luftwaffe, according to the RAF. Some 544 Fighter Command air crew were among the Allied dead. Nearly 2,600 Luftwaffe crew were killed, another 735 wounded and 925 captured. Many of the German casualties were seasoned air crew, a blow from which the Luftwaffe would never fully recover.

More than 40,000 British civilians died in The Blitz that followed, but Hitler’s impetuous decision to exact revenge for the Allied bombing of Berlin proved fateful. By shifting his attention from airfields to London and other population centres, he gave the RAF time to rebuild and reinforce. Frustrated by mounting losses over Britain and, with its populace unbroken, he would eventually turn eastward and open a new front in Russia.

Hawker Hurricanes of Hart’s 67 Squadron, RAF, lined up at Chittagong, India (now Bangladesh), in May 1943. [IWM/IND2143]

“I only encountered [Zeroes] a couple of times. The Japanese pilots seemed to be pretty efficient.”

He later instructed in Egypt, then was posted to 112 Squadron, flying its shark-nosed Mustangs in Italy. He arrived in late February 1945. His logbook shows he had two days to check out on the Mustang before flying his first mission with his new squadron, dive-bombing a bridge.

He closed out the war providing close air support for tanks and conducting low-level ground attacks taking out bridges, trains and railways in Northern Italy, Yugoslavia and Austria.

They were mostly strafing missions, although he often carried a pair of bombs, one beneath each wing, 500- or 1,000-pounders, mainly for bridges. The bomb loads were recorded under the “2nd Pilot, Pupil or Passenger” column of his logbook.

Hart’s log for March 1945 shows almost daily sorties, sometimes two, mainly against bridges. On March 3, flying Mustang No. KH635, he hit the “Casara rail diversion and bridge” in northern Italy. On March 4, flying FB300, he hit it again. Later that same day, flying KH795, he attacked the Venzone rail diversion. The next day, he was in Yugoslavia attacking the Lasko road/rail bridge. And so on.

He flew different aircraft virtually every mission, largely due to battle damage. Air-to-ground combat could get hairy, particularly at low levels where fire was intense and margins of error were minute. “You’d come back pretty shot up from time to time.” Hardworking ground crews were constantly repairing and servicing aircraft.

After logging 1,452 hours, most of it in combat, he was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross, the citation appearing in the London Gazette on June 15, 1945:

“This officer has participated in a large number of varied sorties, including many attacks on heavily defended targets such as road and rail bridges, gun positions, strong points and mechanical transport. Throughout he has displayed skillful leadership, great determination and devotion to duty.

“In April 1945, Squadron Leader Hart took part in an armed reconnaissance during which eleven locomotives were successfully attacked. Some days later Squadron Leader Hart participated in another sortie during which a number of locomotives and trucks were most effectively attacked.

“This officer has invariably displayed the greatest keenness and has set a fine example to all.”

Hart, fourth from right, with squadron mates and a Spitfire in 1940s Britain. [Courtesy Hart family]

In 2016, on the 76th Battle of Britain Sunday, two RCAF CF-18s from CFB Cold Lake in Alberta, did a low-level flyby at his home. Then four generations of Harts took turns sitting in the cockpit of one of the 409 Squadron fighters at the Penticton airport.

Hart did not himself partake, although he had taken a turn aloft in a Harvard on his 100th birthday a week earlier. He dedicated the recognition to “those who fought and died and to those who survived, that we do not forget them.”

A humble and grateful survivor, he’s matter-of-fact about his experiences and the contributions he made so long ago: “We had a job to do and we did it.”

John Stewart Hart passed away on June 18, 2019. He was 102. May he rest in peace.

Advertisement