What was it like to be conscripted during the First World War?

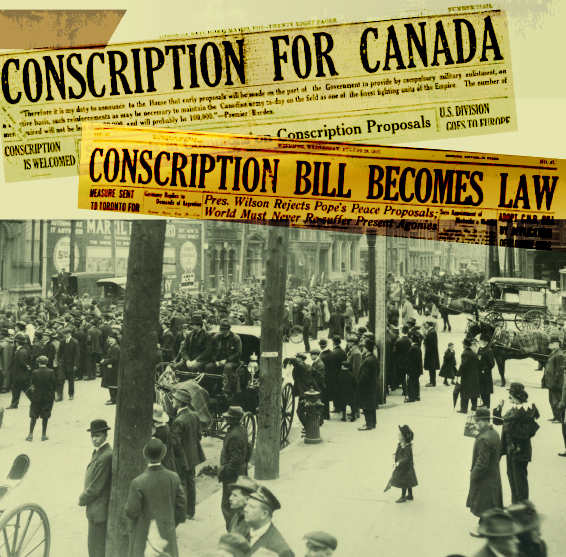

Protesters hold an anti-conscription parade at Victoria Square in Montreal, May 1917. [Manitoba Free Press]

The proclamation was made under the Military Service Act of Aug. 29, 1917, and it meant Rowntree was immediately deemed a soldier on active service and subject to service discipline.

In May 1917, Prime Minister Robert Borden was faced with more than 27,000 Canadian casualties since the start of the year, and recruitment was falling far short of replacing them. So he went against his earlier pledge and called for conscription. Much has been written on how it divided the country, but what confronted men like Rowntree when the call came?

The Military Service Act declared all men who were British subjects between the ages of 20 and 45 liable for service, and grouped them into six classes according to call-up priority. Classes were defined by age, marital status and number of children. Class 1 were those who had attained the age of 20 and were born not earlier than 1883, unmarried or widowers without child. Class 6 were those born between 1872 and 1875, married or widowers with one or more children. Only men in Class 1 were ever called up.

Some exceptions were allowed: members of other dominions’ armed forces, men who had already served and been honourably discharged, members of the clergy, Mennonites and Doukhobors. German and Austro-Hungarian-born immigrants were designated “enemy aliens” and either interned or required to report to local authorities for registration. They could still farm, for example, but were not considered full-rights voting Canadians. And although many First Nations had volunteered, Indian agents could exempt those who were attached to reserves from call-up.

As soon as the proclamation was made, postmasters, along with sheriffs and clerks of the peace swung into action across the country posting up municipal notices. “MEN IN CLASS 1”, the posters began. “GO TO ANY POST OFFICE…and ask the Postmaster for a form of REPORT FOR SERVICE which you will fill in and for which you will be given a receipt. Every man in Class 1 must either report for service or CLAIM EXEMPTION.” The latter required submitting a Claim for Exemption form.

As a Class 1 conscript, Rowntree had until Nov. 10 to report to a post office, fill in one of the two forms, and hand it to the postmaster. Both documents asked for the same basic information: name, residence address, age, marital status, how many children, occupation and employer.

Those reporting for service could expect to be notified by registered mail as to where to report, the first stop usually being a medical examination board. After the medical, they would either return home and await instructions or report for service to a Depot Battalion to start basic military training. Travel expenses were reimbursed.

Rowntree chose the Claim for Exemption form, which, in addition to the basic personal information, required him to put an X in one of eight multiple-choice boxes indicating grounds for his claim:

1. Importance of continuing employment in habitual occupation.

2. Importance of employment in a special occupation for which one has special qualifications.

3. Importance of continuing education or training.

4. Serious hardship owing to exceptional financial obligations.

5. Serious hardship owing to exceptional business obligations.

6. Serious hardship owing to exceptional domestic position.

7. Ill health or infirmity.

8. Adherence to a religious denomination of which the articles of faith forbid combatant service.

All exemption claimants were then called on to face a local tribunal consisting of two members—one appointed by a county or district judge and the other by a parliamentary selection committee, who were each paid five dollars a day (about $79 in today’s equivalent). About 1,390 tribunals were formed across Canada. Municipalities had to provide premises such as schools or municipal buildings but tribunals were responsible for their own “pens, ink, and small quantities of blank paper,” according to a tribunal guidance manual issued by the King’s Printer updated in March 1918.

If grounds of ill health were claimed, tribunals could grant exemption on the spot if a man’s condition was obvious; otherwise they would refer him to a military medical board. If he claimed to be in an industry of national interest, tribunals considered critical the maintenance of the food supply, particularly “fish, meat, and wheat.” If industrial, it was “coal, steel, metal, or timber.” Operations of “railways, steamships, telegraphs, telephones, light, heat and power plants” were considered critical, as was the “machinery of finance,” according to the manual.

There were “humane” grounds too. For example, if two or more family members had already been wounded or killed serving with the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) and you were the sole remaining male family member, you could have a case.

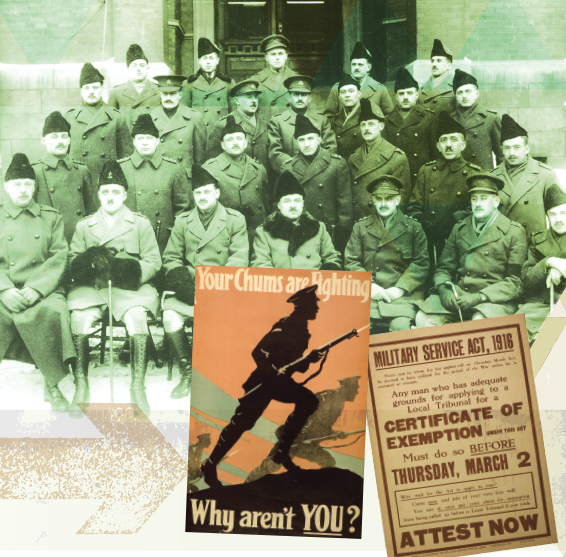

Officers (top) from the first French-Canadian battalion formed under conscription pose for a portrait. Posters encouraged men to report or get a certificate of exemption. Recruiting posters played on negative attitudes that Canadians held for those who did not enlist. [Harry Richards/DND/LAC/PA-022761; CWM/19900053-010; C.J. Patterson/LAC/C-029484]

Decisions by local tribunals could be appealed to the next level: one of 195 appeal tribunals, which consisted of a judge appointed by the province’s chief justice. Decisions by these appellate tribunals could be appealed to the highest level, the Central Appeal Judge, Mr. Justice Lyman Duff of the Supreme Court of Canada. His decision was final.

Tribunal records were ordered destroyed after the war because the government was afraid of exposing some of the vitriolic statements in them. But a few survived the purge, one of which illustrates the concern. A Roy McCauley claimed his brother was wounded overseas so he was the only remaining support for their poor mother. “What would become of your mother if you were to go out on the street and get killed by a motor car?” the tribunal co-chair reportedly demanded. “Don’t look on the black side of things,” he replied. McCauley was drafted.

Fully 94 per cent of the Class 1 men called up sought exemptions. An Oct. 20 report by the Montreal Gazette showed specific cities’ exemption-seeker rates: 98 per cent in Saint John, N.B.; 96 in Kingston, Ont.; 90 in Toronto; 86 in Calgary; and 70 in Vancouver.

Response to the call-up and exemption processing were quick. In Montreal, for example, after two days of sittings they heard 2,595 cases and granted 2,021 exemptions. It helped that many claimants showed up en masse, such as virtually every student from Laval University. Some tribunals granted exemptions in wholesale lots. By Nov. 10, the cut-off date for reporting, 332,000 men from across Canada had been processed, and despite penalties for failing to register, another 70,000 had failed to complete their forms.

By the end of 1917, final results were 404,395 men of Class 1 had reported with 380,510 desiring exemption (278,779 granted by local tribunals) leaving 23,885 who had been willing to serve from the outset. Of 99,651 finally conscripted and available on CEF strength, 47,509 were sent overseas and just 24,132, or six per cent of those originally called, ended up on the front lines.

Under the Act, you had to produce evidence of exemption or reporting. If you did not answer or couldn’t produce the document, you could be detained and brought before a justice of the peace.

It did happen. Local police would sometimes block theatre or dance hall exits and check men for their exemption papers. Patrons who didn’t produce the papers would be frogmarched off to enlistment centres or cited.

Often viewed as slackers, shirkers or malingerers, conscripts’ records of service and even their casualty forms were stamped “MSA” (for Military Service Act) in large bold letters, frequently in red. Moreover, their regimental numbers were prefixed by the letter “D” for draftee.

Conscripts could not choose their service; nearly 90 per cent were assigned to infantry units. Their ignominy continued when they were first shipped in February 1918 to a “segregation camp” adjacent to the main training base at Bramshott in Surrey, England.

With the mass German offensive of spring 1918, conscripts were quickly trained and sent to the front to fight alongside the volunteer soldiers.

And they did their duty. According to military researcher Patrick M. Dennis, who wrote the 2017 book Reluctant Warriors: Canadian conscripts and the Great War, the draftees made up an indispensable part—up to a quarter of the entire Canadian Corps—of the final push that became known as Canada’s 100 Days. Over half the 42,065 reinforcements received by the Canadian Corps during that stretch were conscripts. They saw intense action at Amiens, Arras, Cambrai and Mons; suffering more than 30 per cent casualties. They earned 56 Military Medals for acts of bravery. Indeed, Private George Lawrence Price, the last Commonwealth soldier killed in the First World War, was a conscript from a Saskatchewan farm.

Rowntree stayed on the farm—he was granted an exemption by the Central Appeal Judge.

Advertisement