[Pixabay]

On Nov. 13, 1821, Captain Barnabas Lincoln and his crew, including a Newfoundlander, set sail from Boston aboard the schooner Exertion. They were bound for the Cuban town of Trinidad loaded with foodstuffs and furniture.

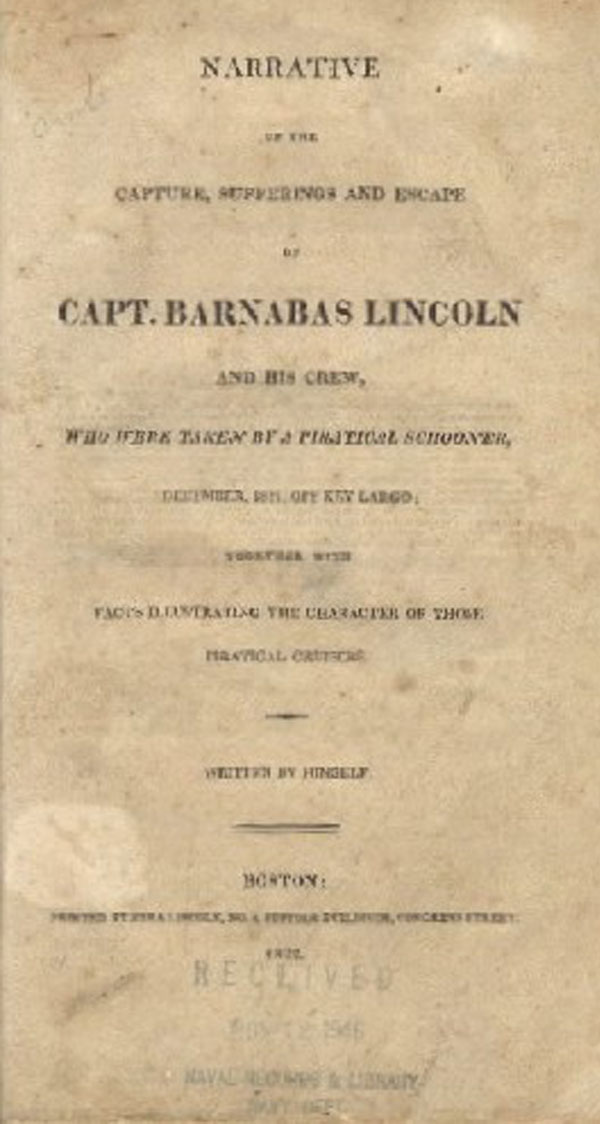

They had no idea what they were in for, but the tome-like title of the skipper’s 40-page account, completed in April 1822, pretty much sums it up:

Narrative of the Capture, Sufferings and Escape of Capt. Barnabas Lincoln And His Crew, Who Were Taken By a Piratical Schooner, December, 1821, Off Key Largo; Together With Facts Illustrating the Character of Those Piratical Cruisers.

Lincoln wrote his account, he said, largely because pirates had “infested” the southern coasts of the United States.

“If this narrative should effect any good, or urge our government to still more vigorous measures for the protection of our commerce, my object will be attained,” he declared.

Plying the East Coast, American privateers—essentially licensed pirates—had played a key role in the War of Independence, taking more than 3,000 British vessels and capturing coveted muskets and gunpowder for the Continental Army.

During the War of 1812, historians estimate, American privateers captured more than $9 million in British commerce, much of it off Halifax, home to many of their British counterparts.

Far from acts of patriotism, the essentially greedy practice created something of a monster that reared its ugly head after the wars ended and their letters of marque expired. Always a threat, piracy had a brief resurgence off North America after the hostilities of nations ended, particularly in the South Atlantic, the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico.

The characters included Frenchman Jean Lafitte, a former privateer known as the “patriot pirate” who operated a warehouse in New Orleans and started a pirate colony on Galveston Island off Texas, and Paddy Scott, an Irishman who terrorized the Alabama coast in the 1820s and 1830s.

Lincoln was just a trader working for New England financiers and entrepreneurs. His crew of six comprised an Englishman from Bristol, a Scot from Grennock, three Americans and a Newfoundlander—Francis de Suze of St. John’s, apparently a transplanted Spanish fisherman who was tearfully press-ganged into the piratical service soon after Exertion was waylaid, ostensibly because he shared the same heritage as his captors.

“I shall do nothing but what I am obliged to do and will not aid in the least to hurt you or the vessel,” de Suze promised Lincoln. “I am very sorry to leave you.”

Exertion had been transporting about $8,000 ($172,000 US today) in flour, beef, pork lard, butter, fish, beans, onions, potatoes, apples, hams, furniture and bundles of boards, called shooks, to assemble into sugar boxes—probably in which to store her return cargo.

Things, however, did not go as planned for Capt. Lincoln and his crew. Or, as Lincoln put it: “Nothing remarkable occurred during the passage, except much bad weather, until my capture.”

They were less than 200 kilometres from their destination and “all seemed favourable for a happy termination” of their voyage when, at 3 p.m. on Dec. 17, 1821, Exertion’s crew sighted a schooner making right for them, and not in a friendly way. She was flying a Mexican flag.

As she neared, they saw about 40 men on the vessel’s deck armed with muskets, blunderbusses, cutlasses, long knives and dirks, along with two small cannons.

Thinking it prudent not to resist with a crew of seven and only five muskets, Lincoln ordered his arms and ammunition hidden in the hope that their Spanish-speaking visitors would act with “honour and friendship.”

“How great was my astonishment, when the schooner having approached very near us, hailed in English, and ordered me to heave my boat out immediately and come on board of her with my papers.”

While Lincoln was boarding the schooner Mexican, however, six or eight heavily armed Spaniards were boarding Exertion. No sooner had he begun to parley with her captain, a Spaniard named Jonnia, than the two vessels were under sail again.

By 6 p.m., they were anchored in the shelter of an island.

Portrait said to be of Jean Lafitte. [Rosenberg Library, Galveston, Texas]

As he handed Lincoln back his documents, Monacre warned him: “Take good care of them, for I am afraid that you have fallen into bad hands.”

Bad hands, indeed.

Lincoln describes his captors as wretched, ill-mannered and unprincipled desperadoes “wearing black whiskers and long beards, the receptacles of dirt and vermin.”

“They used continually the most profane language; had frequent quarrels; and so great was their love of gambling that the captain would play cards with the meanest man on board. All these things rendered them to me objects of total disgust.”

They recently had what he called “a stabbing match,” in which one man was almost killed. There were three girls aboard, “of whom it is well to say no more.”

Lincoln was briefly allowed to return to his ship, where he found Bolidar—the pirate ship’s first lieutenant—and his boarding party had emptied his liquor cabinet and, to his mortification, had crumbled cheese all over the table and cabin floor.

“The pirates elated with their prize…had drank so much as to make them desperately abusive,” he wrote. “I was permitted to lie down in my [berth]; but reader, if you have never been awakened by a gang of armed desperadoes, who have taken possession of your habitation in the midnight hour, you can imagine my feelings. Sleep was a stranger to me, and anxiety was my guest.”

Bolidar feigned friendship and raised the prospect his prisoners might soon be freed. Lincoln wasn’t buying it, describing the man as “a consummate hypocrite.” Even his looks suggested it, he wrote.

Portuguese by birth, Bolidar was “a stout and well built man, of a dark, swarthy complexion, with keen, ferocious eyes, huge whiskers, and beard under his chin and on his lips four or five inches long.”

He was, it seemed, supervising the looting of Lincoln’s ship.

As they set sail again, Capt. Jonnia dispatched boats to take stores from Exertion, which were consumed “with great waste, and extravagance.” His captors had found his apple barrels, selected the best of them, and threw the rest overboard.

Back aboard the Mexican, Lincoln was miserable and abused.

They drank his cider stores and “a violent quarrel arose between officers and men, which came very near ending in bloodshed.”

In the evening, peace was restored and the pirates sang songs.

Lincoln was sent below with a guard. They gave him food and drink, but it was, “of bad quality, more particularly the victuals, which was wretchedly cooked. The place assigned me to eat was covered with dirt and vermin.”

He cultivated a relationship with Monacre, who had sailed out of New Orleans before falling in with the pirates.

Monacre said the Mexican’s crew would hang for sure, and swore he’d “never be hung as a pirate.” He took a bottle of laudanum from Lincoln’s medicine chest, saying, “If we are taken, that shall cheat the hangman before we are condemned.”

Eventually Lincoln, most of his crew and four Spanish prisoners were deposited with rudimentary provisions and an old sail for shelter on a small, sandy island shaped like a half moon and partly covered with mangrove trees.

There was no escaping the flies, much less the island. They were 80 kilometres off traditional sailing routes, and 250 from Trinidad.

The pirates spent the days offshore, dismantling Exertion, refitting their own ship, and transporting the remaining cargo for sale to unscrupulous buyers in Cuba.

They resupplied their captives a couple of times, laughing at their miseries.

“My resentment was excited at such a malicious outrage,” Lincoln wrote, “and I felt a disposition to revenge myself, should fortune ever favor me with an opportunity.”

It was, he said, perhaps assuaging his own guilt at feeling such hostility, “beyond human nature not to feel and express some indignation at such treatment.”

Narrative of the Capture, Sufferings and Escape of Capt. Barnabas Lincoln And His Crew, Who Were Taken By a Piratical Schooner, December, 1821, Off Key Largo; Together With Facts Illustrating the Character of Those Piratical Cruisers. [Ezra Lincoln, Boston 1822 / U.S. Navy Department Library]

They also had a small kettle, a broken pot, an old sail, a small mattress and a blanket. One of the prisoners happened to have a little coffee in his pocket. The ground beneath their feet was crawling with insects, scorpions, lizards and crickets.

Their ship had been run aground 25 kilometres away, picked clean and stripped of her masts, spars, rigging, furniture and provisions.

“Look at us now, my friends,” Lincoln wrote, “left benighted on a little spot of sand in the midst of the ocean, far from the usual track of vessels, and every appearance of a violent thunder tempest, and a boisterous night.”

“We began to suspect we were left on this desolate island by those merciless plunderers to perish.”

Indeed, soon after the prisoners were deposited at their new home, the Mexican set sail and was never seen again. It was Jan. 20, 1822, more than a month after Exertion first encountered Jonnia and his motley crew. “I assure you, we were very wretched; and to paint the scene, is not within my power.”

The days passed. Hunger and sickness set in, although the sea currents brought them modest bounty in the form of Exertion’s shooks and two long planks, which, along with some timber, they began fashioning into a boat.

On the night of Jan. 28, crewman David Warren of Maine died. They dug him a grave and boxed it up with shooks, “thinking it would be the most suitable spot for the rest of us—whose turn would come next, we knew not.”

They finished the boat a few days later, but it was too leaky for all to sail. Lincoln decided on six—four to row, one to steer and one to bail. He stayed behind.

They set off at sunset on Jan. 31, “into the wide ocean, with strength almost exhausted, and in such a frail boat as this, you will say was very hazardous, and in truth it was; but what else was left to us?”

“Their intention was to touch at the Key where the Exertion was, and if no boat was to be found there, to proceed on to St. Maria and if none there, to go to Trinidad and send us relief. But alas! It was the last time I ever saw them!”

By Feb. 6, the provisions were nearly gone, “our mouths parched extremely with thirst; our strength wasted; our spirits broken, and our hopes imprisoned within the circumference of this desolate island in the midst of an unfrequented ocean.”

Yet there, “in the midst of this dreadful despondence, a sail hove in sight, bearing the white flag. Our hopes were raised.”

It was a freshly shaven Monacre and two others, with food and wine. “Do you now believe Nickola is your friend?” his rescuer asked.

Their ordeal was far from over but, eventually, an emaciated Lincoln and what remained of his crew arrived at Boston by way of Cuba on March 25, 1822.

He finished writing his account less than a month later. It was published on the U.S. Naval History and Heritage website in November 2017.

Advertisement