On July 5, 1944, the millionth Allied soldier landed in France. The lodgement phase of Operation Overlord—codenamed Neptune—was over. The port of Cherbourg was secure and to everyone’s surprise the supply system, using the remaining Mulberry (artificial) Harbour and the open beaches, was working smoothly. No operation can succeed without solid logistical support and the Allies were bringing manpower and materiel to Normandy more quickly than the enemy.

By early July, Allied strengths included total mastery of the air and sea, plus an intelligence system that allowed the Supreme Allied Commander, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and his senior commanders to accurately gauge German strengths and intentions.

The situation was very different for the enemy. On the eastern and western fronts, Hitler and the High Command had made basic errors. They had expected the Soviets to launch their summer offensive in the south and were quickly overwhelmed when the attack came in the centre. They had been so certain the Allies would land in the Pas de Calais that even after weeks of intense combat in Normandy, reserves were still stationed between the River Seine and the Scheldt.

But despite these advantages the Allied ground offensive seemed in danger of stalling and the prospect of a stalemate—reminiscent of the First World War—loomed. The battle for Carpiquet, like a number of other engagements fought by British Second Army in June and July 1944, illustrated a fundamental criticism of General Bernard Montgomery’s conduct of the campaign. Too often it is argued that Montgomery committed a brigade rather than a division, a division rather than a corps and a single corps when the whole resources of the army should have been brought to bear on the enemy. One explanation for this policy, which brought sharp comments from Eisenhower’s headquarters as well as from soldiers in the field, is that he did not want to attack without massive artillery support, and the build-up of supplies in the bridgehead was much slower than expected. There was no easy answer to the problem confronting Montgomery and his army commander Sir Miles Dempsey. The bitter complaints of battalion commanders who cursed limited attacks because they allowed the full weight of German artillery and mortar fire to be brought to bear on a small section of the front are hard to argue with, but no one wanted to attack without the largest possible measure of artillery support.

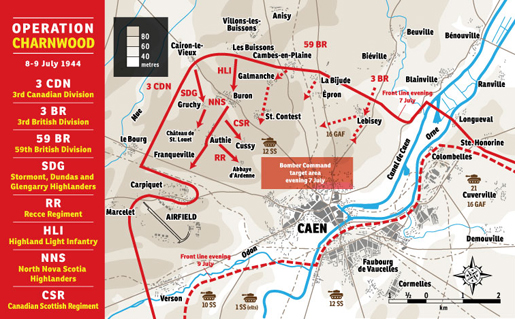

For Operation Charnwood, the attack on the German-held city of Caen, Montgomery had decided to use three divisions of 1st British Corps. A front of eight miles would be struck on July 8. To supplement the artillery and naval guns, joined Bomber Command in the preliminaries. This was to be the first use of heavy bombers in direct support of the army and no one knew exactly how to obtain the best results, or what to expect. Fear of bombs hitting Allied troops led to the selection of a “bomb line” three miles beyond the Allied positions. The area chosen, a rectangle along the northwest edge of Caen, was well inside the ring of fortified positions held by the Germans. The vast armada of Halifax and Lancaster bombers arrived over the battlefield on the night of July 7, six to eight hours before the infantry assault.

All reports agree that for the Allied soldier in his slit trench, the never-to-be-forgotten sight of an endless stream of bombers blasting away at the enemy was an enormous boost to morale. It is equally clear that rear-echelon German troops received a tremendous shock in the dramatic demonstration of Allied airpower. Unfortunately, the bombing had no impact on the capacity or will of the Germans to resist in the defensive perimeter. The destruction of large parts of Caen and the death of many civilians must also be added to the balance sheet.

The old problem of an open flank which had confounded the Canadians on June 7 was to be overcome by folding the front in from the left with the 3rd British Division and newly arrived 59th British Div. starting off for Galmanche and St. Contest well before the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade once more took the road to Carpiquet.

The Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders were ordered to seize the village of Gruchy and the buildings around the Château de St. Louet. Lieutenant-Colonel G.H Christiansen decided to take Gruchy with just two companies, keeping two in reserve for the second objective. Gruchy was on the outer edge of the defended area and the Glens had direct assistance from the Vickers medium machine-guns of the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa and the armoured cars of 7 Recce Regiment (17th Duke of York’s Royal Canadian Hussars).

This additional support proved especially valuable in the second phase when the mobility and firepower of the armoured cars provided close support. Lt.-Col. T.C Lewis reported “the best shooting of the whole operation occurred when the cars swept in to cut off the enemy’s retreat.” For the Glens, Charnwood involved very “severe and close fighting” with significant casualties. However, their story is overshadowed by the much more costly assault on Buron, a village crucial to the German defence of Caen. The Highland Light Inf. of Canada, Waterloo County’s regiment, was selected for this task.

There had been ample time to study the German positions around Buron. In addition to ground observations, air photographs—when viewed through stereo glasses—offered a detailed three-dimensional picture. Anti-tank ditches, designed to force Allied tanks into killing zones, were protected by camouflaged machine-gun posts. Air photos showed signs of other enemy activity which confirmed an interrogation report on a prisoner captured by the North Nova Scotia Highlanders on July 5. The young Hitler Youth soldier talked freely about the dispositions of the 3rd Battalion, 12th S.S. Panzer Div., right down to platoon positions for his own company. He described a network of weapon slits linked by communication trenches and camouflaged by waist-high grain fields. “Concertina wire was erected along the front of the platoon position…” and anti-personnel mines sown behind the wire. “In front of the wire there was a tripwire attached to egg grenades and a flare device….” According to the prisoner, his platoon “was up to strength in LMGs (Light Machine Guns) 2 per section….”

Lt.-Col. F.M. “Smokey” Griffiths planned to attack two companies up, saving his reserve companies for the final objective which was represented by a ring contour on topographical maps that was to be the start line for the second phase of the advance by the North Novas.

Brigadier D.G. Cunningham, commanding 9th Canadian Inf. Bde., had been assured that an advance by the 59th British Div. would capture or neutralize the villages of Galmanche and St. Contest, a move that would protect 9th Brigade’s left flank. But as the minutes ticked away there was no sign of the British, and it became too late to change the artillery fire plan or make arrangements for a smokescreen. The Sherbrooke Fusilier tank squadrons needed no reminding of the threat they faced because the skeletons of their burnt out Shermans from June 7 were still plainly visible.

The HLI moved through the waist-high wheat fields, taking casualties from the flank and German field guns. The anti-tank ditches, it was noted at the time, “were almost like a World War I trench system of bays and shelter areas requiring hand-to-hand fighting.” B Company was held up at the “trench system” until tank support arrived. D Company pressed forward into Buron with Sergeant A.P. Herchenratter, a soldier who became a legend in the battalion, leading the remnants of two platoons to the orchard, their final objective.

Griffiths ordered his reserves forward and with elements of all four rifle companies at work, Buron was cleared. The HLI war diary describes the situation: “At 1130 hrs the C.O. was able to get to his Coy Commanders by means of a runner and learned the state of affairs.” Three of the four companies were at or below half strength while A Company still had two-thirds of its men available. “Mortaring and shelling from St. Contest and Bitot on the left flank were exacting a heavy toll by the minute.”

Griffiths and his command group established a headquarters on the west side of Buron and began to redeploy his companies. The ring contour which the operational plan had described as high ground “was merely a flat open field and Colonel Griffiths did not consider he was justified in sending troops from the village out into the open to seize something that was not dominating ground.”

He discovered that while none of the surviving Sherbrooke tanks had been able to reach the village, the 245th Battery Royal Artillery, detached from the corps anti-tank regiment, had come forward to an orchard on the southeast corner of Buron. They were busy camouflaging their self-propelled 17-pounder guns and checking fields of fire to cover approaches to the village because German doctrine called for an immediate artillery strike on any position captured by the Allies followed by a counterattack led by armoured assault guns or tanks.

As predicted, the counterattack came from the southeast. Very little was known about this engagement until Captain Tony Foulds, who served with the 62nd, wrote an account in the article, In Support of the Canadians, available online at canadianmilitaryhistory.ca > Journal-CMH > Back Issues > Vol. 7 (1998): Issue 2, pp 71-78.

Foulds writes, “a battle group of 20 to 30 Mk IV’s and Panthers moved across the front of the gun positions and in the ensuing action 13 enemy tanks were destroyed before the remainder withdrew. This was the most celebrated British anti-tank engagement of the Normandy campaign.”

Buron would not be overrun, but the battalion battle was far from over. German artillery scored a direct hit on a HLI orders group, killing Lieutenant C.W. Sparks and three signallers and wounding the CO and two of his remaining company commanders. This brought the day’s casualties to 262 of which 62 were fatal. The Sherbrooke tank squadron lost 11 of its 15 tanks and the British anti-tank battery was standing guard with just one of its eight guns undamaged.

The British overcame resistance in St. Contest early in the afternoon, and Cunningham ordered the Glens to seize their second objective while the North Novas attacked through Buron to capture Authie, the village that had witnessed the murders of their comrades on June 7. Both objectives were taken after a concentrated artillery bombardment.

The threat from Hussars armoured cars and the advance of 8th Bde. from Carpiquet to the edge of Caen forced the 3rd Bn. 12th S.S. to withdraw to Cussy and the Abbaye d’Ardenne where elements of 2nd Bn. were preparing to hold the inner defensive perimeter. After the war, Kurt Meyer, who commanded the 12th S.S., claimed he had repeatedly requested permission to withdraw across the River Orne, and finally did so against orders. This, like so many of Meyer’s stories, is pure invention. The 12th S.S. moved rear echelon and support units across the Orne as ordered July 8. The front-line soldiers had one more battle to face: defending a series of well-fortified positions against British and Canadian attacks.

On the Canadian front, the 7th Inf. Bde., which had been waiting all day to carry out Phase 3 of Operation Charnwood, stayed well back until Authie was cleared. The story of the Regina Rifles, Canadian Scottish and Royal Winnipeg Rifles on July 8 and the advance into Caen on July 9 will be the subject of the next article in this series.

The battle for Buron was analyzed by Major F.A. Sparks who commanded Headquarters Company. He noted enemy artillery was used against Buron while the battle raged because his own troops were so well dug in. “Troops should not yield to the impulse to take cover behind stone walls…as this may be fatal under mortar fire.” Instead, they “should push on to the far edge of the village…supporting companies should go to the flanks, not directly into it.” The crucial role of the anti-tank guns was a key lesson as was the value of the division’s LOB (Left Out of Battle) policy which had persevered a core of officers and NCOs to help re-organize the battalion. Sparks also drew attention to the challenge of the timely evacuation of casualties. Lives depended on prompt action so “large stretcher-bearer parties are necessary.” The high wheat fields presented a special problem that required a careful search of the ground “preferably with one man from each platoon retracing the course travelled.…” This had been done at Buron and many wounded men were found early enough to save lives.

Email the writer at: writer@legionmagazine.com

Email a letter to the editor at: letters@legionmagazine.com

Advertisement

![CoppLead Soldiers from the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade examine a disabled German tank at Authie, France, July 9, 1944. [PHOTO: LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA114367]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/CoppLead.jpg)

![CoppInset1 German prisoners are escorted by a Canadian soldier at Buron, France, July 7, 1944. [PHOTO: KEN BELL, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA151168]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/CoppInset1.jpg)