The story of the wrecking of two U.S. destroyers on Newfoundland’s rocky shores 75 years ago in a blizzard and the heroic rescue of 186 sailors by local miners and townspeople.

- .

- 0

- .

i

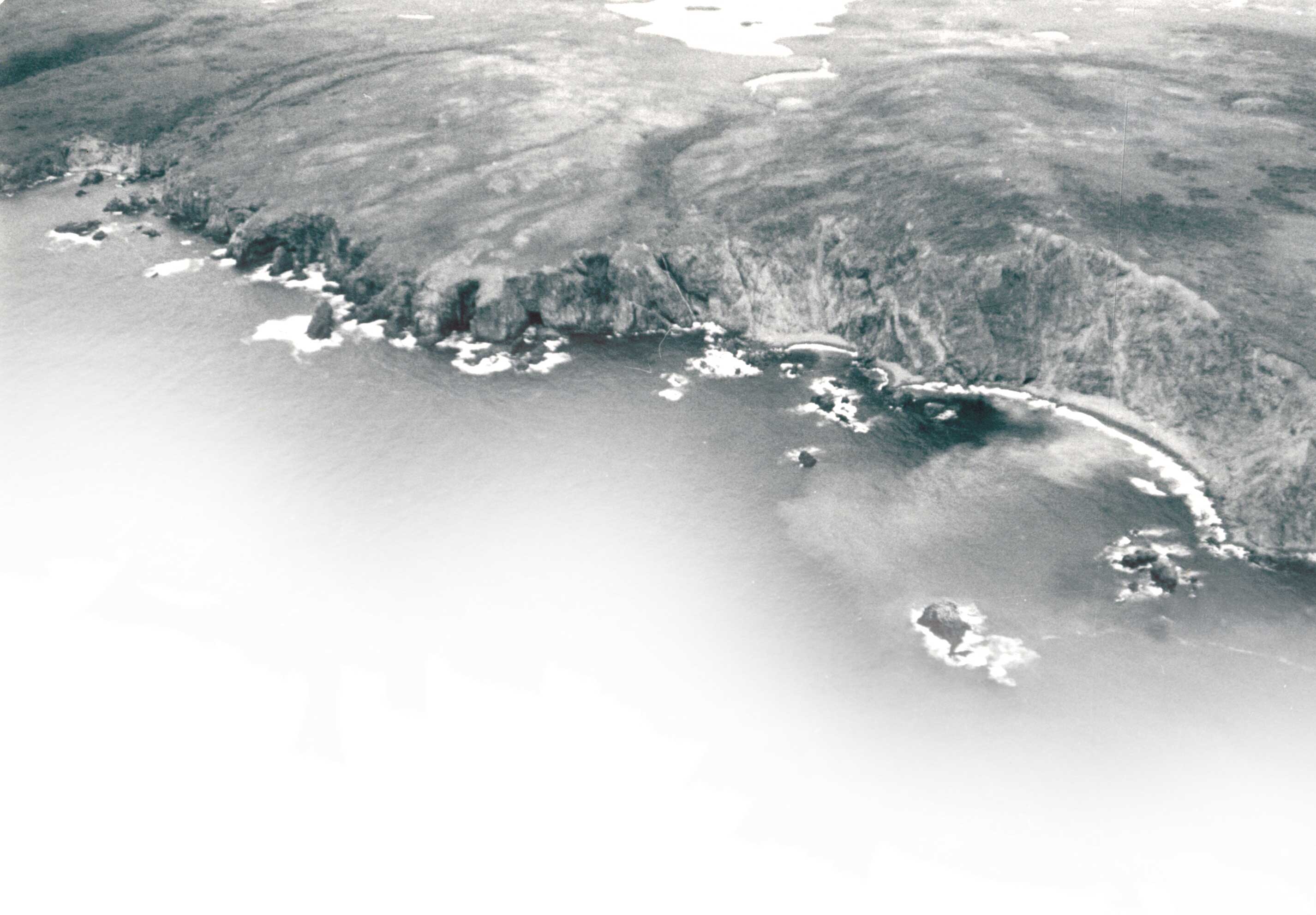

The rugged Burin Peninsula located along the southern coast of Newfoundland, Canada. [Maritime History Archive, Memorial University, PF-306.983. John Cardoulis Photograph Collection.]

Hover over the info icons located on the top left corner of photos to learn more about the images.

THE WILD BEAUTY of the Burin Peninsula, which juts, boot-shaped, into the sea on Newfoundland’s southern coast, is testament to the great natural forces that formed and rule The Rock: tectonic shifts of the earth that crushed together parts of three continents to form the island, ceaseless wind, rocky shores constantly reshaped by gentle tide and pounding surf.

The tough and resilient people who for centuries have lived along this sparsely populated coastline, the miners, foresters and fisher families, know this is a land of raw and elemental beauty that can take the breath away—or stop it altogether.

In water that is 0 degrees Celsius or below, hypothermia induced unconsciousness sets in within 15 minutes and estimated time of survival before death is only 15 - 45 minutes.

In water that is 0 degrees Celsius or below, hypothermia induced unconsciousness sets in within 15 minutes and estimated time of survival before death is only 15 - 45 minutes.

Wind and water are treacherous. Especially in winter. From the Arctic the Labrador Current carries down frigid water. Gale winds and ferocious tides smash upon the shore, push whitecaps high up cliff walls, scour everything off ledge and outcrop, bash it on the rocks and suck it out to sea. Blizzards plummet air temperature well below freezing, with bone-numbing wind chill, while water temperature drops below zero. At these temperatures, anyone plunged unprotected into the water will be incapacitated within 15 minutes, dead shortly after.

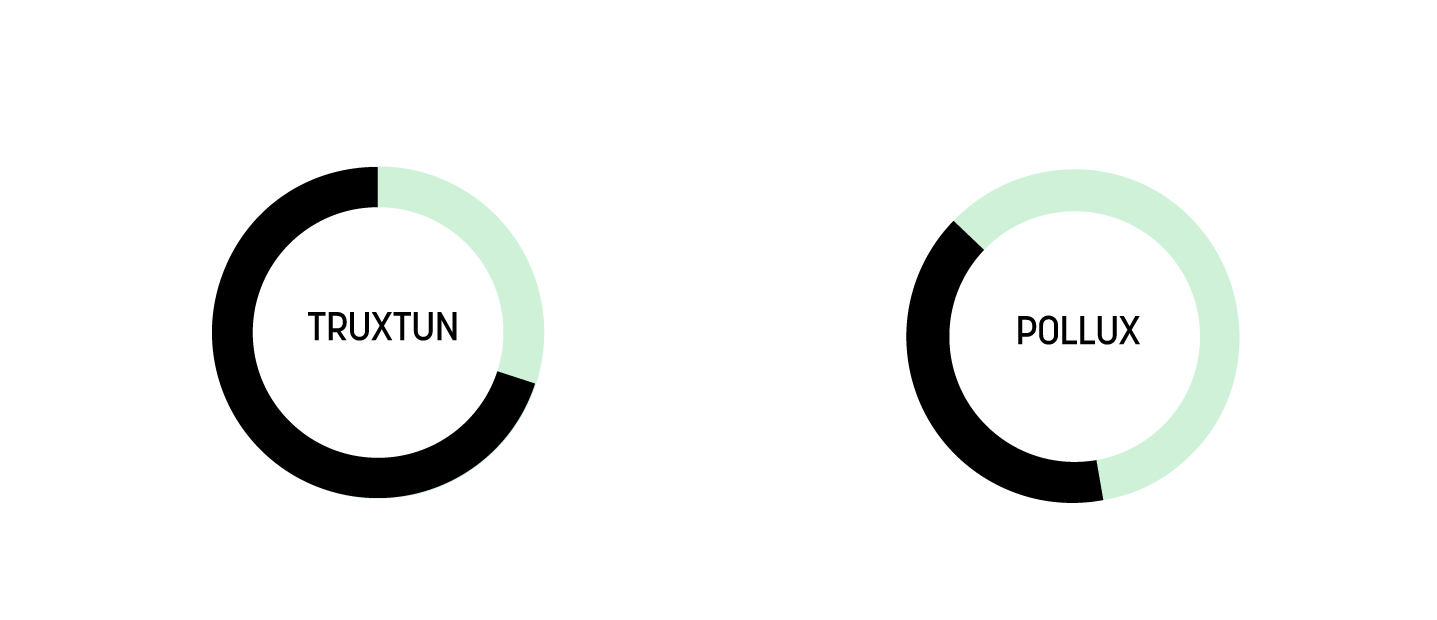

It was in these pitiless conditions, under the towering cliffs of Lawn Head and Chambers Cove, that 389 men aboard two wrecked U.S. ships fought for survival in a blizzard Feb. 18, 1942; 203 perished. None would have survived but for the help of the brave and generous people of nearby towns St. Lawrence and Lawn and surrounding communities. Only one rescuer still lives, Gus Etchegary of St. John’s, and it’s believed all survivors are gone now. But their stories live on in recordings from survivors, books, newspaper stories, navy records and the oral history of families on The Rock.

i

The USS Pollux was a supply ship carrying cargo for delivery to Argentia at the time of her grounding in 1942. [Maritime History Archive, Memorial University, PF-306.983. John Cardoulis Photograph Collection.]

Inauspicious Beginnings

On Feb. 17, 1942, the USS Pollux was sailing from Casco Bay in Maine for the U.S. Naval Air Station Argentia, bordering Placentia Bay, in what was then the Dominion of Newfoundland. She was loaded with cargo including bombs, radio equipment and aircraft engines, plus 58 recruits headed for training and 16 military passengers.

The supply ship was escorted by destroyers USS Wilkes, under Commander John Kelsey, and USS Truxtun, captained by Lt. Cmdr. Ralph Hickox. Wilkes was the flagship, carrying senior officer Cmdr. Walter Webb. The others in this small convoy were to follow its lead as it ran the gauntlet of German U-boats on a zigzag course through torpedo alley, without lights and under strict radio silence.

They had reason for caution. The first wave of a murderous eight-month U-boat campaign, ordered after the U.S. entered the war following the attack on Pearl Harbor, had already destroyed a couple of dozen ships, and would eventually sink hundreds down the East Coast of North America to the Gulf of Mexico. “Several submarines had been reported in this area, the day before,” Webb noted in a report. Icebergs were also a worry, as was heavy weather. A winter gale sharply reduced visibility. Only the Wilkes had radar; the other ships were wary of colliding with one another in the stormy night.

“She looked like a floating coffin. I guess

we all had the same premonition...”

Many sailors were uneasy. Pollux fireman Lawrence Calemmo started the voyage worried. The Pollux had just been converted for navy use, and his first impression was unfavourable. “She looked like a floating coffin. I guess we all had the same premonition, that the ship was going to get…torpedoed by a U-boat,” he said in interview recordings posted on the Dead Reckoning website. But soon there were other worries. “We were in full gale winds of 60 knots, seas 20 to 40 feet and visibility was zero. More than once we almost collided with Truxtun. Cmdr. Turney paced the deck of the bridge all day and all night; he knew we were in danger.” Not able to shake the bad feeling, Calemmo installed makeshift heaters under the hood of the lifeboat engines so they would start immediately in an emergency.

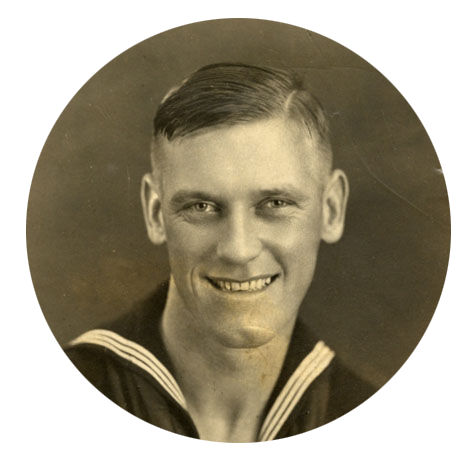

“I slept fully clothed with my life jacket nearby,” said worried Truxtun mess attendant Lanier Phillips.

Aboard Wilkes, navigator Lieutenant Arthur Barrett, unable to see the stars to fix position, used dead reckoning—a calculated estimate of current position based on the last night before. The ship was actually about four kilometres from where he thought it was, the Truxtun and Pollux plowing blindly along behind in the storm. Adding to this, Cmdr. Webb thought the current would offset any drift from course caused by the wind, and made no leeward allowance. He plotted a course he thought would bring them into the middle of Placentia Bay, with kilometres of sea room either side for safety. He was dead wrong.

Meanwhile, the experienced navigator on the Pollux, Lieut. William Grindley, was fretting. Several times he recommended they stop zigzagging, and was refused, Turney constrained by orders to follow course decisions of the Wilkes. Grindley pleaded for a 30 degree course change to keep the ship out of danger. Finally, Turney agreed to a 10 degree change, but would not abandon the zigzag course. It was not enough.

Small errors by inexperienced crew and weather-related equipment failures aboard the Wilkes contributed to the tragedy. Unexpected changes in depth were not reported to officers and communications about convoy course changes not received. They also did not know the newly-installed radar was unreliable if it iced up. Wilkes expected land to show as a series of blips, so a single blip was mistaken as a ship. It really indicated land.

i

The ancient four-stack destroyer USS Truxtun, which ran aground and sank in Chambers Cove, Newfoundland. [Archives and Special Collections, Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University, 16.06.213. Cassie Brown Collection.]

Disaster before dawn

Just after 4 a.m., the water was suddenly shallow, multiple radar blips appeared and a wall of white abruptly loomed ahead of the Wilkes. Kelsey ordered an emergency course change. Too late. At 4:09, Wilkes ran aground near Lawn Head. Ice coating the radio equipment prevented transmission of an emergency warning to Pollux and Truxtun. Even the siren was frozen. In the quarter hour it took to clear the equipment of ice, the other ships ran aground, too.

Although Kelsey was able to work the damaged but maneuverable Wilkes off the rocks by about 7 a.m., the other two ships were in bad shape. The Pollux was impaled at Lawn Point, less than a kilometer eastward, and the Truxtun grounded about two kilometres further east in Chambers Cove. The wind, waves and current were too wild for Wilkes, and other ships and boats that arrived to help, to come close enough to render aid. The wrecks could only be reached by land—and it was a long trek through deserted and frozen countryside to the Pollux site.

Click to listen to Lanier Phillips recall his final moments on board the Truxtun.

Most crew in the ships were asleep when disaster struck. They raced topside into the night, some not dressed for the cold, and were dumbstruck by what they saw. “They had the search lights playing on the cliffs, and my God, bleak nothing…rocks, waves, whitecaps,” said Pollux storekeeper Alfred Dupuy. “Waves as high as a building slamming up against the reefs.” And over the ship’s deck.

George Coleman, amidships, saw waves climb 12 to 15 metres up the cliffs, then “come tumbling down in a great white foam and bang against the side of the ship (and come) close to the top of the railing.

Turney was unable to back the Pollux off the rocks. Worried it would sink in deep water if it broke apart, and thinking cargo might still be salvaged, he rammed the ship hard aground. The bottom ruptured, fuel oil spilling into the sea. Watertight doors were locked down against flooding holds, and water was seeping around the bulging bulkhead plates in the engine room. Enormous waves were breaking over the ship. “I saw those waves coming in at an angle and pounding, crashing down on the bow, and the bow was being torn up,” said Pollux boatswain mate George Coleman. “I believe there must have been a crack underneath, for waves would come back from cliff, foam amidships and suddenly be sucked under the ship.”

i

The wreckage of the U.S. Navy supply ship Pollux lies aground off the Newfoundland coast, where it foundered in a storm February 18 with many lives lost. [Maritime History Archive, Memorial University, PF-306.983. John Cardoulis Photograph Collection.]

Emergency flares were fired over the desolate cliffs, to no immediate effect. [The lights were glimpsed, then the ship, during a lull in the snowstorm by Webbers Cove teenagers Adolph Jarvis, out hunting seabirds, and Ken Roul doing chores, but they were miles—and hours—away from anyone who could help.]

Hickcox, too, tried to back off the rocks, but the Truxtun’s screws were torn off. Waves lifted the ship, slammed it down, rolled it side to side between two great rocks. The hull was pierced, releasing fuel oil which soon coated the cliffs around the horseshoe bay and created a peel of sludge on the water.

The engine room was flooding. Steam was let out to prevent explosion, the light and heat cut off, the watertight doors closed. Ferocious waves were breaking the ship apart.

About two kilometres apart, the Pollux and Truxtun captains separately came to the same reluctant conclusion: the crew would have to abandon ship. But a defiant sea raged between their ships and the shore, denying them the land.

Dawn, Truxtun

The crew goggled at the sheer granite and shale cliffs surrounding Truxtun, rising raggedly up 90 metres, too high and too far to fire a lifeline. But a sliver of beach lay a tantalizing 200 metres away, and the early light revealed a fence running along the lip of the cliff above it.

“I watched men being washed overboard, and I saw men trying to swim and being tossed on the rocks.”

“I had no immediate fear,” said Phillips. Then a tremendous wave crashed over the deck. “I watched men being washed overboard, and I saw men trying to swim and being tossed on the rocks.” The crew soon understood their peril.

The Truxtun was coated with ice and some crew had rushed onto deck without warm clothing and now compartments were flooded. Some lost their footwear to waves and as the morning wore on, bloody footprints showed where bare feet met steel deck. Soon men began to freeze to death. Harry Egner watched a barefoot crewman salvage shoes from a dead shipmate.

Attempts at launching lifeboats failed, the crafts destroyed, as were some life rafts. The surviving three flipped upside down when they hit the water, and work began to right them. A sailor who jumped into the sea to try to turn a raft over was instantly paralyzed by the cold, and swept away before he could be rescued.

William Harris thought he could swim ashore, and jumped over the side, followed by some others. Egner watched as a wave grabbed them, pulled them under the oil slick, then lifted them high up the rock face, and dropped them onto rocks below. The death toll slowly mounted as the hours went by.

At last one of the life-rafts was righted. Hickox asked Egner if he could paddle it to shore, towing a light line connected to the ship. Kneeling on the grating in the raft, he and James Fex sank to their waists, shocked by the icy water, the stench of oil gagging them and stinging their eyes, and headed for open ocean, hoping waves would push them ashore. It worked. They hauled in the line and a secured it to a big rock. Some men righted the other life rafts, and grouped together on the rafts, used the line to pull themselves ashore.

“I thought I was cold until I jumped in the water. It felt as if a knife had gone through my heart.”

Phillips was among the two dozen who made it by raft to shore. “I thought I was cold until I jumped in the water. It felt as if a knife had gone through my heart. I was temporarily paralyzed from the shock…The men on the raft pulled me onboard…I felt as if I had not slept for weeks, knowing that if I got to sleep I would never wake again.”

As the evacuation continued, Edward Bergeron began to inch his way diagonally up the cliff, followed by Edward Petterson, leaving a line dangling for others. A barren and snowy landscape awaited, a shed the only shelter in sight. Leaving Petterson, now too cold to continue, Bergeron set off to seek help.

Stumbling and numbed after fighting through sleet and snow drifts, Bergeron spotted the light atop a mine tipple. He arrived at Iron Springs Mine sometime after the 8 a.m. shift started.

The people of the Burin Peninsula have vast experience with what’s needed in the face of disaster. Immediately the mine was shut down so the men could respond, and townspeople of St. Lawrence alerted.

Miners Mike Turpin, Sylvester Edwards and Tom Beck gathered equipment at hand and headed towards Chambers Cove, three kilometres from the mine, five from town. Soon others followed, miners and men from St. Lawrence, Lawn and surrounding communities, bringing more equipment.

The women were busy, too. An emergency first aid station was set up in the mine’s dry house, stocked with food from pantries of nearby residents, extra blankets from their beds and clothes from their own closets. Women started preparing hot drinks and food, for they knew the survivors would be cold to the bone.

i

Iron Springs Mine, St. Lawrence, Newfoundland. [Archives and Special Collections, Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University, 16.06.048. Cassie Brown Collection.]

Daybreak, Pollux

Dawn revealed Pollux, icy deck canted, trapped about 20 metres from a rocky ledge that seemed the only place to land beneath the 30-metre cliffs of Lawn Point. If they could get a line to shore, the crew could be shifted off the ship. But whole compartments were flooded, including the armoury; the only line-throwing gun was underwater.

The sea was pounding so hard the men had to hold on to keep their feet, icy railing freezing their hands, water blown by the wind soaking and freezing clothing and hair. The crew managed to lower lifeboats, but wild waves flung them back to shatter against the ship.

So they turned to life-rafts, chopped out of the ship’s icy grip. After a first attempt failed, Ensign Alfred Pollack and Lieut. James Boundy felt they could make it if they stripped down, their bodies covered with grease for some protection from the brutal cold. They tried paddling ashore, but were continually tossed back. Numb with cold, they were brought back aboard.

Next the crew repeatedly flung a grapnel hook at the shore; finally until it snagged in a crevice.

Quartermaster Henry Strauss, a college diving and swimming champion, volunteered to work his way, hand over hand, to shore. But a giant wave knocked him off and he was pulled back aboard. A little later, he volunteered again to crawl over a rope ladder at the end of a cargo boom—but it proved a few metres too short to bridge the gap.

Click on the map for a closer view of the wreckage sites and surrounding areas.

LAWN TOWNSHIP

Brave residents of Lawn travelled through the night in snow and freezing temperatures to help save survivors of the shipwrecks along the coast.

WEBBERS COVE

Two teens spotted the Pollux from Webbers Cove and made their way by ox cart to Lawn in order to send help for the men aboard the ship.

THE USS WILKES

A destroyer in the United States Navy, the Wilkes, was the leading flagship of the convoy headed to Argentia, Newfoundland in February 1942.

THE USS POLLUX

A supply ship in the United States Navy. It had been carrying a cargo of bombs, radio equipment, aircraft engines, and other supplies during its fatal mission.

ST. LAWRENCE

The mining town that joined nearby communities to help with the effort to save the men shipwrecked on February 17, 1942.

The USS TRUXTUN

A four-stack destroyer in the United States Navy that had been sent to protect the supply ship Pollux and transport troops.

Midmorning, Pollux

“It’s difficult for me to describe the feeling that you are standing on a ship that’s falling to pieces and the land is almost so close you can touch it, but you can’t get to it,” said Pollack. “Many things run through your mind. If you’re going to see the sun come up, or if this is the end, and what kind of end it’s going to be.”

Convinced he would not survive, Strauss went into the flooded compartment below, took a picture of his wife from his locker and tucked it inside his lifejacket. “When they found my body, they’d find the picture on it and she would know that I’d thought about her.”

Five men—Jack Garnaus, Garrett Lloyd, Warren Greenfield, William DeRosa and Lawrence Calemmo volunteered to try the one remaining boat. A line was tied to one of their lifejackets, Calemmo worked the engine of the small wooden whaleboat while Lloyd struggled to keep it heading to shore. A wave picked up the boat and smashed it into shore rocks, throwing the men into the water on opposite sides of the craft. “We finally climbed onto the ice-covered rocks and crawled on our stomachs up and away from the surf,” said Calemmo. Relief quickly turned to anguish—they were trapped in a cleft of rock.

The others came to shore on a small plateau, now covered with ice and oil. Despite the bitter cold sapping their strength, they began to pull the lifeline, that was soon attached to a heavier line, which they hoped could support a breeches buoy that could be used to transfer crew from the ship.

Soon their strength gave out. They tied the rope to a rock and signaled the ship that they were going for help. Then, up the cliff and over—only to find a desolate landscape buried in snow. “They looked like three black ants climbing out of the steep gorge,” Strauss said in Reader’s Digest. “It seemed as if our only hope for rescue went with them. The chart showed nothing but desolate country for miles.”

While the others sheltered in a ravine, where they were shortly joined by more sailors, Garnaus began exploring.

Meanwhile, the great cracks in the hull of the Pollux were spreading.

Click to listen to Alfred Dupuy describe his escape from the grounded Pollux.

Before noon, the bow broke away, the remaining hulk tilted alarmingly, brutal waves threatening to haul it off into the sea. “The after part on which all of the men were located seemed to be about to capsize,” Turney reported later. “Those men who wanted to attempt swimming or getting ashore on floating wreckage had permission to go overboard…The major number of those who did not survive were lost at this time.”

Ninety men slid down lifelines and cargo nets into the wild sea and a world of agony. The men aboard watched as shipmates died, some screaming for their mothers, others shouting warnings not to follow. The lifejackets of some had slipped up over their heads and arms, preventing swimming.

“I see my friend George (Marks) and three other men completely drawn under the ship,” said George Coleman. “(Other men) commenced to disappear. One by one they went under the ship. Then there are no more voices from the sea. I knew those men did not last more than three to five minutes.”

The water was littered with bobbing bodies. Only a score of men made it to shore, eight pulled out of the surf and the muck by Lloyd and Calemmo, the remainder making landfall on the plateau.

At midday, when hope was fading for the hundred still aboard the Pollux, the teens from Webbers Cove who had glimpsed the Pollux, had made their way by ox cart to report the wreck to residents of Lawn, who had already heard of the Truxtun disaster. Could there be a second ship aground at Lawn Point, some 15 kilometres away?

Skeptical, but not wanting to turn their backs on anyone in peril, 10 men gathered rope, hand lines, cod jiggers an axe and horses and set out, among them self-educated miner Joseph Manning. Two turned back. “It was a teruable climb out over that Point over Mountens of hill & through woods. It was a hard Journey & not Nowing if there was a Man to be Saved or Not,” Manning wrote in a letter in March 1942.

i

Men lower themselves by rope over the snow and ice-covered cliff to the beach below, still searching for bodies. [Archives and Special Collections, Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University, 16.06.135. Cassie Brown Collection.]

Midmorning, Truxtun

Meanwhile, at Chambers Cove, evacuation had halted. The life-rafts had become hopelessly entangled in the lifeline and couldn’t be budged. Great cracks rent the Truxtun, the rear had broken off completely and the hulk was almost on its side. The mast snapped off and the forward section broke away.

Hickox passed the word that anyone who wanted to swim for it could try. Sailors started to go over the side.

As this deadly decision played out, Turpin, Edwards and Beck, rescuers from the mine, reached the clifftop, and saw about 100 men clinging to safety lines over the Truxtun's side, and a few men in the water, some clinging to debris.

The miners climbed down the rope left by Bergeron, waded into the surf and began hauling oil-covered survivors out of the water. Soon other rescuers arrived, eventually there were as many as 70. “As we came up over the hill and looked down, 300 feet or so below, right in the middle of a horseshoe cove, this destroyer…partly submerged…all these people hanging on, if you like, to dear life. Some were just swept up on those jagged cliffs and then tumble down. It was a pretty dreadful sight,” rescuer Gus Etchegary said in a radio documentary.

i

Newfoundland men hauling bodies up on the cliffs of Chambers cove on the day following the disaster. [Archives and Special Collections, Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University, 16.06.049. Cassie Brown Collection – Ena Farrell Edwards photo.]

Realizing the survivors were too cold to climb, the Newfoundlanders tried pulling them up the cliff, but the sailors arrived battered, too weak to push off when bashed into the rocks on the way up. Nothing for it but to carry them up. The sailors, clothes weighted down and slick with oil, were carried and hauled one by one to the clifftop.

Once the survivors reached the clifftop, those able to walk were then led along a shortcut to the mine. Others were carried on horse-drawn sleds. Strauss was walked to the mine by 18 year old Wallace Rose, who “took the gloves off his hands and the coat off his back and gave them to me as he brought me to the mine.”

Rescuer Lionel Saint spotted some floating debris, wreckage that could not have come from Truxtun. He walked off to investigate.

Rescuers waded into the water in a futile attempt to free the tangled rafts formed themselves into a human chain to help swimmers to shore, and soon were as wet, frozen and covered in oil as the survivors. Some sailors drowned, others were picked up and smashed by waves, some perished trying to swim through the oil, which in places floated atop the water in a layer thicker than a man’s head. Heartbreakingly, some reached shore only to die there shortly of exposure.

A series of great waves washed over the ship, each taking dozens of men. One swept away the bridge and everybody in it; the captain was not to be among survivors.

A survivor was spotted, terrified, clinging to a rock under the tallest cliff. Henry Lambert of St. Lawrence tied a rope around his waist and, with a dozen men holding on, was lowered down. The two were hauled to safety.

Meanwhile, Adam Mullins arrived with a dory, which was quickly lowered and launched, rescuers Mullins, Charlie Pike and Dave Edwards aboard, a lifeline stringing behind to the beach. Seconds from the ship, a wave swept Pike into the water, some sailors were washed away and one was tossed into the dory. Pike grabbed onto the side of the dory as men began to pull it into shore. Donald Fitzgerald, the last man clinging to the ship, launched himself at the dory and grabbed onto a rope. But a wave tore it from his hands. Luckily, he was thrown onto the beach. The dory carried the last man from the sea at about 3 p.m.

By four, said Etchegary, all the survivors had been taken up the cliff, and collection of the dead had begun.

Noon, Pollux

As Garnaus explored the clifftop, he spotted a man in the distance: not the navy rescue team that was expected and hoped for, but Lionel Saint, who had left the Truxtun site to investigate mysterious wreckage.

Saint led five survivors to the Iron Spring Mine, a three-hour walk through the snow drifts. Along the way, DeRosa died.

Meanwhile, some of the men who had abandoned Pollux made it to shore near a rocky ledge that extended to within throwing distance of the disintegrating ship. But who would leave safety to catch a line? A barefoot Dupuy, who’d lost his shoes to the sea, volunteered. “I got on my hands and knees. I was afraid…there would be crevices and holes, and hell, I’d step in one and be gone.” He stopped at a sheet of ice edging the water. Lieut. Grindley threw him a line with a telephone receiver attached. Dupuy caught it. His hands had lost all feeling, so he needed to use his teeth to pull over enough rope to secure to a boulder.

A breeches buoy was quickly rigged, and tall and brawny Ensign Edgar Brown volunteered to test it. At about 2:30 p.m., men started making their way from the ship to the ledge.

“For a few minutes before we realized what a predicament it was, we thought ‘well, we’re out of this now,’ because it was solid, unmoving ground,” said Strauss. “ (But) we were at the base of a cliff on a ledge and no way of getting up. The tide was coming in. Guys started getting picked off one by one. I thought ‘Oh shit. This is it.’ I remember another guy and myself reaching for a seaman named (James) Hill who was standing right behind us., He got washed off by a wave. We reached his collar, but couldn’t hold him.”

By 4:30 p.m., about 120 men had reached the ledge, but now were on precarious footing.

“We had to form in one line because the higher we climbed, the ledge became narrow,” said Coleman. “You had to be very careful of your footing because that cliff was all ice. Darkness had commenced to set in…the waves are pounding against the cliff. We can hear the roar of the sea below us.”

The sun was setting, and those on the ledge and the dozen sheltering in the cleft with Lloyd and Calemmo could feel the temperature dropping. They were all still in dire straits.

“All of a sudden out of the blackness we heard a voice saying, ‘Is anybody there?’ The next thing I knew these guys were being hauled up the cliff,” said Strauss.

Click to listen to George Coleman share his harrowing journey across the icy cliffs.

The men from Lawn—Joseph Manning, James Manning, Andrew Edwards, Martin Edwards, James Drake, Thomas Connors, Alfred Grant and Bob Jarvis—arrived.

“They warent like human Beings at all,” Joseph Manning wrote. “All cruid oil & some poor fellows dying & more dievin around in the water. It wasant Nice to Look at. Twenty Minutes after five in the eving & everything was in a Sheat of glitter and you had to watch your steps.”

Soon they began, five men to a line, hauling men up. “This went on for hours, a couple of Newfies from the village of Lawn spent the whole night pulling one man up at a time,” said Strauss, who was hauled up himself by Drake, who with Connors had gone over the side to help men on the ledge. Connors gave his cap and mitts away. “Up a 250 reverse angle cliff in the snow and a partial gale. They did it; I don’t know how,” said Strauss.

“It wasent long before we where all good a wet,” wrote Manning. “It was heging to close in dark,” Too dark and stormy to travel to the mine or towns, he took some survivors to shelter in a nearby copse and cut up boards from his sled to start a fire. “We credits ower Selves for Helping to haul up one Hundred & thirty Seven Men that Night But (some) died by the fire.”

A half dozen of the first survivors to reach the top, including Pollack, elected to walk to St. Lawrence. “I felt personally if I was going to die, I was going to die moving.”

Meanwhile, Saint and survivors had reached the mine. Men cold, exhausted and covered in oil from the rescue at Chambers Cove went back into the cold for the long trip to Lawn Point, joined by medical officers from the U.S. Navy. They arrived when all but about 30 men had been hauled up from the ledge.

At last Turney, who refused to leave until the last of his men was safely off the ledge, was pulled up. “Abut two o clock we hauled the Captan & I Just tell you we where Some Glad ower arm hauled out & ower Backs Broken & Starving to Death Besides.” When they returned home, their hands were raw and covered with blisters and open cuts.

The rescuers had been pulling men up for more than eight hours, but there were still men in the cleft, and they had begun to die. “I now learned that freezing to death is very easy and quiet,” said Calemmo. “It seems you just get tired from lack of circulation and go to sleep. I don’t remember how many froze in the cleft.”

An officer asked for volunteers from the crew to help the men up. “They were perty misserable & it was very hard work trying to Bring them up that hill in Blanket it was Some Hard Sights Bear footed Men & No Boots on in a winter Night.” The Newfoundlanders went to work again, though Manning said “we were pretty laggey.”

Soon Calemmo was jolted by the sound of falling ice and rock. “I saw what I thought was a miracle—an angel from heaven or God Himself.” Ropes tied around their chests, the last of the sailors was pulled to the top of the cliff after midnight.

As the freezing men gathered around the fire, the fight began to keep everyone alive to morning’s light. “We have one man lying there (storekeeper Paul Pulver). He’s completely frozen and is dying so we…worked on him for 15 to 30 minutes and brought him back to life,” said Coleman. “We had his legs going back and forth. We had his arms going up and back, rubbed his face, rubbed his neck. Three or four men we had to drag to their feet and make them walk. Keep moving, don’t sit down, don’t lay down, keep on your feet. This went on all through the night.”

Despite their efforts, by dawn a few more men had frozen to death. Sleds were filled with the injured and unconscious from the Pollux and pulled back to the mine, about eight kilometres away, those who could walk following behind.

i

Alonzo Walsh and Celestine Giovannini (right) of St. Lawrence helped the Americans bring up two bodies from the beach. [Archives and Special Collections, Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University, 16.06.059a. Cassie Brown Collection – Ena Farrell Edwards photo.]

Warm Welcome

When the Truxtun survivors began arriving at the mine, they were given soup, tea and coffee and put into warm baths.

Women spent hours scrubbing oil off the skin of sailor after sailor and gently cleaning it from their swollen eyes. They dressed the men, some semi-conscious, in dry clothes and sent them to homes of St. Lawrence families, who watched over them all night, placing hot stones in their beds and warming them up with hot tea or soup.

Lanier Phillips, the first black man the Newfoundlanders had ever seen, was astonished by his treatment. The other four African Americans aboard, believing they had hit Iceland and might be lynched when they got ashore, refused to leave Truxtun, and perished. Phillips was taken aback when rescuers did not kick him aside to help white sailors first.

And now he was naked in a room with white women—a lynching offence in his home state, Georgia. He heard Violet Pike exclaim the oil must have gotten into his pores, and he had to stop them scrubbing him raw. “It’s the colour of my skin,” he said. “ You can’t get it off.” She took him into her home, where he was further astonished by her kind nursing, and being welcomed to sit and eat with the family. Aboard ship, he was not allowed to join white shipmates at table, and had to eat standing up in a pantry.

Others were as warmly welcomed. Don Fitzgerald, who arrived delirious, was cared for by Clara Tarrant, who even persuaded the U.S. Navy to leave him in her care an extra day to more fully recover. Lillian Loder cared for Ensign James Seamans, desperately ill as well as frozen, throwing up oil he’d swallowed and drifting in and out of consciousness.

As Truxtun survivors slept in their hosts’ beds, Pollack’s party arrived at the mine, the first of the Pollux survivors who in their turn were warmed up, fed, cleaned of oil and sent on to a host family. Pollack was sent to the home of Albert Grimes, where despite morphine injected by a navy doctor, he cried as the frostbite worked its way out of his flesh.

i

L-R: Leo Loder, Sue Farrell, Aubrey Farrell, Cecil Farrell, [Stanislaus Kendzierski], John Arthur Shields, Gertie Etchegary and John Alfred Brollini (front) in St. Lawrence the day following the disaster. [Archives and Special Collections, Queen Elizabeth II Library, Memorial University, 16.06.134. Cassie Brown Collection – Ena Farrell Edwards photo.]

Many of the women had stayed up through the night looking after their charges, but came back to the mine to help with the Pollux crew. The survivors who’d walked from the wreck site arrived in midmorning.

“I remember women taking their own petticoats and tearing them up to help the survivors,” said Pollack. “We were a pretty sorry bunch, most of us cut and bruised, all of us covered with fuel oil or grease and most of us frozen. My hands and feet were frozen, I had no feeling in them whatsoever.”

“They gave us whatever food they had—and they didn’t have much,” said Dupuy. “They were desperately poor.”

Tarrant also took in Harold E. Brooks, blind from smoke exposure, one foot bare. She put silver nitrate drops into his eyes, which shortly cleared up.

Sadly, tender care didn’t save Pollux survivor Phillip Jewett, the final fatality from the wreck, who died Feb. 19 at 11 p.m.

The U.S. Navy transported the survivors to the base in Argentia. George Coleman, like many other survivors, spent time recovering in hospital. “I don’t know how much damage was done to my body, but I was in hospital for three weeks. My body now bloated and I was a great balloon in the bed. My feet were cold, my whole body was cold.”

The grim business of recovering bodies continued for months on Newfoundland shores and many islands in Placentia Bay. Not all remains were found. About 150 seamen were temporarily buried in Newfoundland, their bodies returned to the United States after the war.

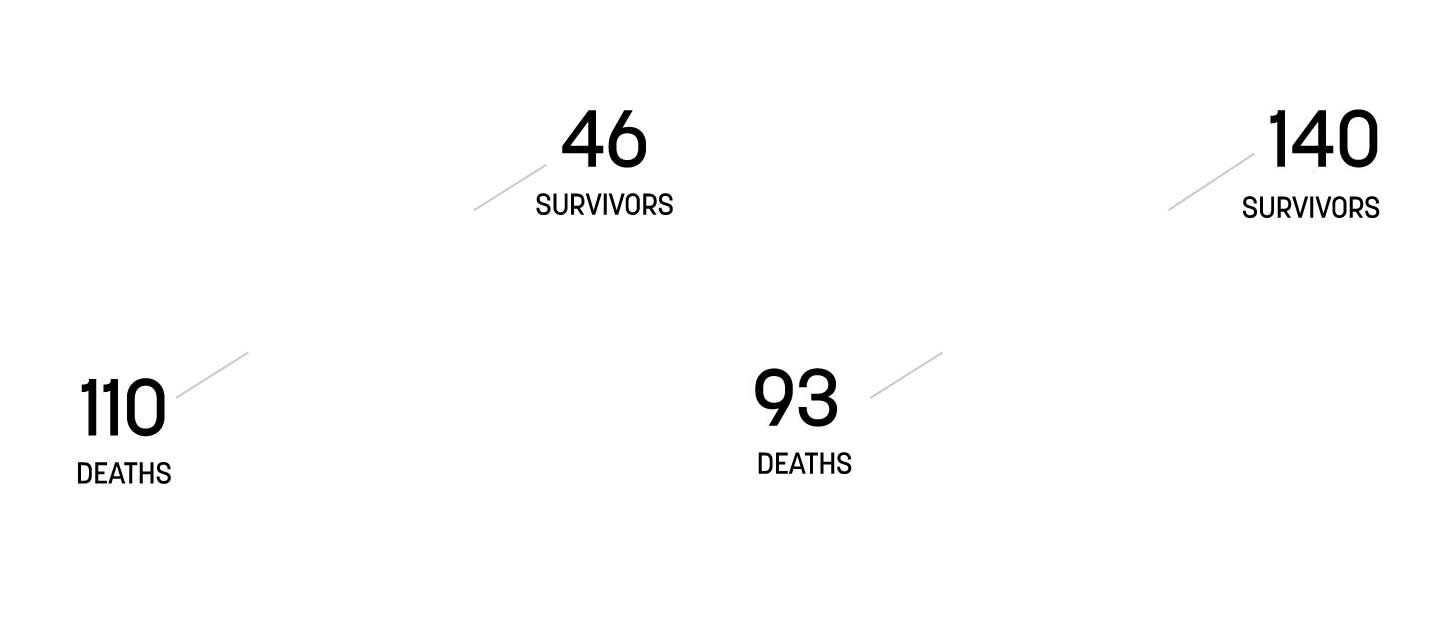

Of the 156 aboard Truxtun, only 46 survived; 93 on Pollux perished. Dupuy counted himself lucky to be among the 140 Pollux survivors. “I was cited for bravery, given a U.S. Navy and Marine Corps Medal (the highest award for non-combat bravery) and given a commission, and my rescue work had a great deal to do with that,” said Dupuy. “And all that was nothing compared to the fact that by God, I lived, and it wasn’t easy.”

The Continuing Story

Since that last dreadful night, people both sides of the border have worked to ensure that the sailors, survivors and the perished, and their rescuers and caretakers are not forgotten. Lawn Head and Chambers Cove wreck sites have been designated municipal historic sites, and the coastline of the disaster redesignated The Truxtun-Pollux Shore. A commemorative service is held each year in St. Lawrence and Lawn on the anniversary of the tragedy. More than a thousand people are expected to attend the 2017 commemoration, said Laurella Stacey, of the St. Lawrence Historical Advisory Committee. Many events are planned throughout the year to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the disaster—performances of songs and plays about the wrecks and the life of Lanier Phillips, craft exhibitions, storytelling. Unveiling of a new monument in Chambers Cove is planned for the memorial service on Feb. 18.

The U.S. government built the U.S. Memorial Hospital in St. Lawrence in recognition of the “dauntless valor...fortitude and generosity displayed by the heroic people of Newfoundland.” Ironically, many of the rescuers spent time here as they recovered from or succumbed to the accidents and diseases that stalk miners. The hospital served the communities for decades and now that it has been retired, the U.S. Memorial Health Centre perpetuates the name and houses the displays that commemorate the tragedy.

The parents of Perique Gomez donated a wine cruet for use in his memory for communions to Lamaline Anglican Church, where their son was initially buried. Strauss donated $31,000 to Holy Name of Mary Academy in Lawn; Phillips donated money for a playground in St. Lawrence, which was named in his honour.

In the 1980s, Royal Canadian Legion members Harold and David Fitzpatrick, Korean War veterans, erected a cross at Lawn Point, which still remains practically inaccessible from land. A cross and plaque were erected at Chambers Cove in 1988, and a hiking trail added as the cove has become a popular destination for pilgrims of remembrance and tourists. The first phase of a 16-kilometre trail linking Webbers Cover to Little Lawn Point has been completed. Completion of the second phase depends on funding, says committee chair Betty Anne Drake. “It’s still a rugged, ugly shore—even on a calm day,” said Drake. “It would be difficult to make a rescue even today.” And for tourists, the terrain is forbidding.

Echoes of Valour, an evocative Luben Boykov sculpture of a miner pulling a sailor to safety, was erected in St. Lawrence in 1992 to memorialize mining victims, Pollux and Truxtun sailors, and those who fought and died during the two world wars. There are displays dedicated to the disaster in the Miner’s Memorial Museum in St. Lawrence, the Room of Remembrance in Lawn’s Heritage Museum, and many other places. A memorial was unveiled at Webbers Point in 2013 and in 2014 underwater videos showed debris and wreckage—artifacts of the tragedy—littering the seafloor where the waves claimed Pollux and Truxtun.

Now relatives of survivors are contributing artifacts to ensure the names of their loved ones are not lost to history. “A couple of years ago the brother of Stanley Rooker, of the Truxtun, donated to the Miner’s Memorial Museum the sailor’s last letter home and the telegram telling the family he had been lost at sea. “He said his dad had clung onto those his whole life, and now that he’s getting older himself, he wondered what to do so Stanley doesn’t get forgotten,” said Cindy Edwards, the museum’s project manager.

But perhaps the most touching memorial is the abiding international friendship that grew between some survivors (and families of the dead) and the Newfoundlanders, relationships that have been passed along to succeeding generations.

“My grandmother took in Ensign James Seamans,” said history buff Tony Loder. “Seamans came back for four or five visits afterwards, and brought his children more than once.”

“Every Christmas and holiday we get emails and cards from people from all over the U.S.” said Etchegary. He keeps in contact with the nephew of Clifford Parkerson. The lone signalman left alive, he refused rescue so he could communicate with those stuck aboard Truxtun. “He stayed on that beach for four hours. He eventually died.”

Etchegary’s brother Theo found a letter in the dead man’s pocket, which he later forwarded to Parkerson’s family. Parkerson’s brother came to visit the Etchegary family in St. Lawrence several times, bringing his children. And now one Parkerson’s nephews continues to visit Etchegary and his wife in St. John’s. “We are friends.”

Betty Anne Drake was looking forward to a fall meeting with the daughter of Henry Strauss, who was carried up the cliff by her husband’s relative, Jim Drake.

Many people are proud of the example set in the rescue and aftermath.

Loder, who lives about a kilometer from Chambers Cove, estimates he’s guided 60 groups a year, every year for years, to the site, and has no plans to stop.

“St. Lawrence added something to the fight against racism,” said Loder. “It showed it’s not that way everywhere…[and] motivated one individual to change his life. I’m proud of that.”

“It’s a story about a disaster, yes,” said former mayor and historian Wayde Rowsell. “But it’s also a story of kindness, compassion and humanity and everything good. [It’s] about those attributes of caring and doing what you can for others. About respect and tolerance and humanity. About rising above adversity.

“It’s a story that has no end, that should never have an end.”