Introduction

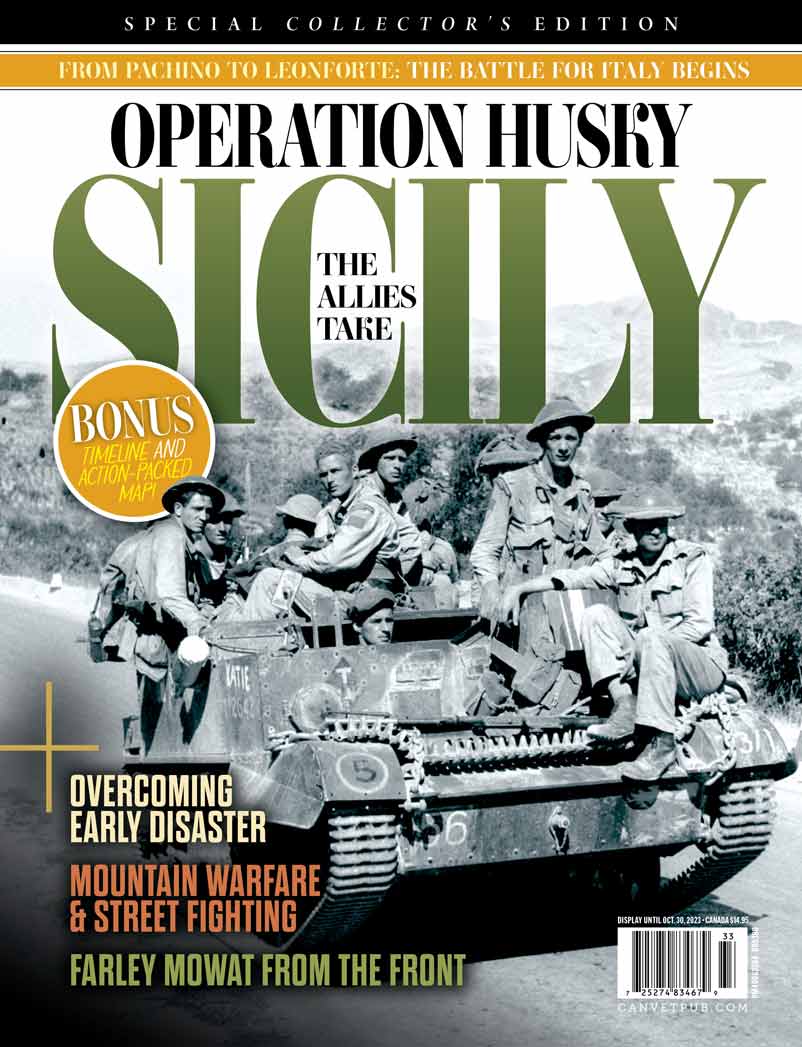

The Allied liberation of Europe began with the invasion of Axis-occupied Sicily by some 160,000 Allied soldiers on the night of July 9-10, 1943. Supported by naval gunfire, tactical bombing and close air support, American forces, including paratroopers, landed along the central stretch of the island’s south coast while Canadian and British troops hit the beaches at Sicily’s southern tip and up the southeast coast.

The Canadians participated at the insistence of Prime Minister Mackenzie King and the Canadian military headquarters in Britain. The 1st Canadian Infantry Division under Major-General Guy Simonds and Major-General Frank Worthington’s 1st Canadian Tank Brigade landed at Pachino.

The fighting in Sicily ended on Aug. 17—one month, one week and one day after it began. Fascist Italian troops and the forces of Nazi Germany were eradicated in Sicily, Mediterranean transit routes were opened to Allied merchant ships for the first time since 1941, and mainland Italy became the Allies’ next objective.

Once the fast Assault Convoy—the last of the 125 ships and escorts of the Canadian convoys bound for the Mediterranean—had sailed from Clyde on Scotland’s west coast on June 28, 1943, 1st Canadian Infantry Division’s two most senior officers engaged in a daily, early-morning battle-planning ritual.

General Staff Officer Lieutenant-Colonel George Kitching shook a hat filled with equally-sized paper chits, each bearing the name of one of the ships, which combined carried 26,686 troops and all their necessary equipment. Division commander Major-General Guy Simonds drew three chits, which were considered lost to German U-boat torpedoes.

If all three ships were part of the fast convoy—carrying most of the division’s troops and those of 1st Tank Brigade—the outcome was particularly stark: vital equipment, such as 1st Brigade’s tanks could be lost, and sometimes as many as 1,000 infantrymen might be drowned or burned in oil-drenched seas.

WET FEET

HMS Eskimo, a Tribal-class destroyer, was heavily damaged by two German bombers during Operation Husky.

Once the daily toll was determined, Kitching and his staff calculated the impact on the forthcoming invasion and how to compensate for it. On July 3, however, Simonds drew three chits that sent a chill through the two officers.

City of Venice, St. Essylt and Devis were freighters sailing in the Slow Assault Convoy, but their loads consisted of equal portions of the trucks, Jeeps, radio sets and a vast array of essential equipment for the divisional headquarters. One of these lost was bad, two a crisis—but the HQ could still function. Lose all three, and the division would be crippled. Kitching declared the “chance of all three ships being sunk was a million to one” and the implications not worth analyzing. Simonds agreed, drawing three other chits.

LUCK OF THE DRAW

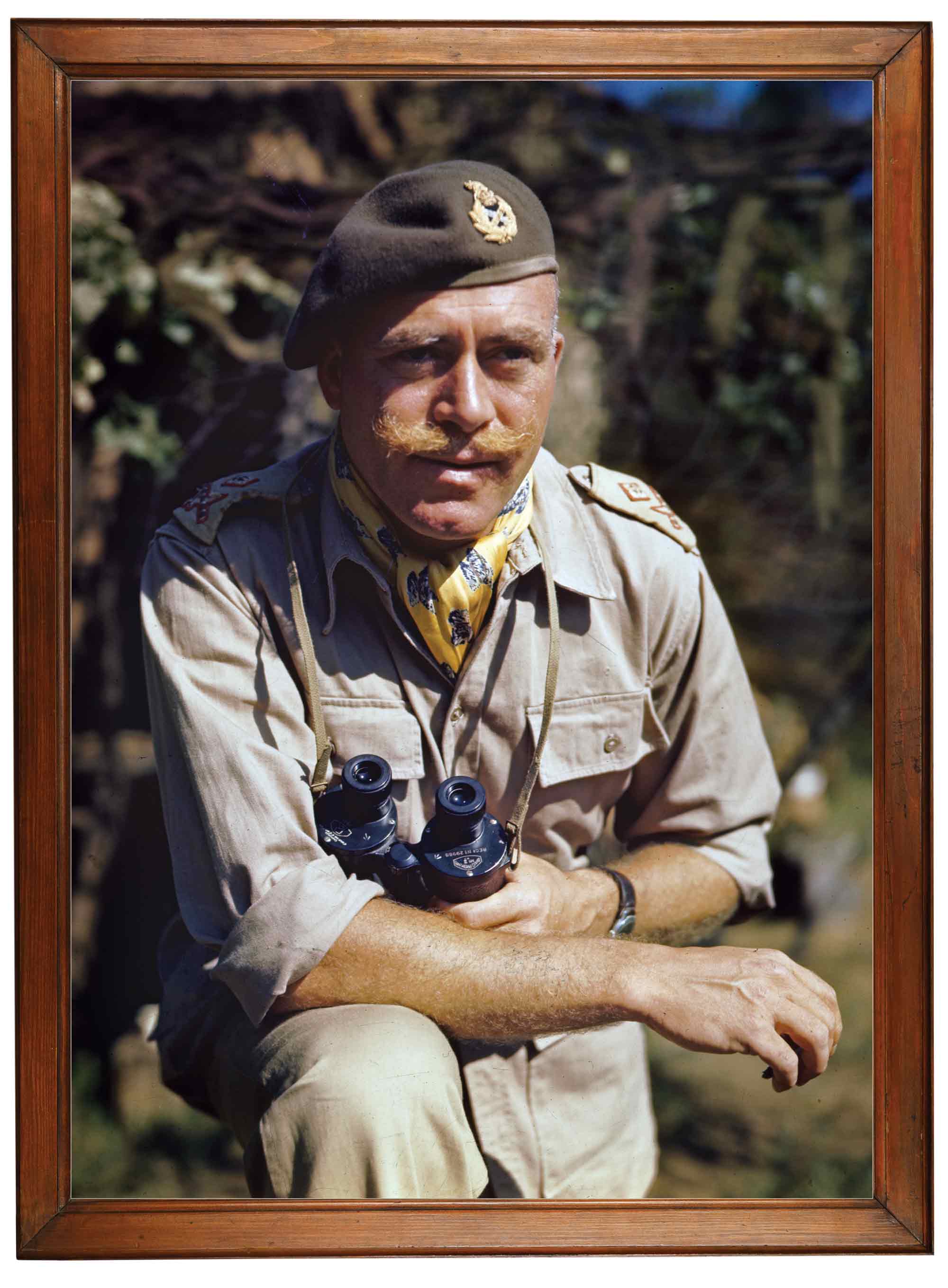

Simonds and Lieutenant-Colonel George Kitching (above) devised a war game where they drew lots to create scenarios in which different convoy vessels were sunk. The exercise forced them to come up with alternatives to their battle plan.

Once the fast Assault Convoy—the last of the 125 ships and escorts of the Canadian convoys bound for the Mediterranean—had sailed from Clyde on Scotland’s west coast on June 28, 1943, 1st Canadian Infantry Division’s two most senior officers engaged in a daily, early-morning battle-planning ritual.

General Staff Officer Lieutenant-Colonel George Kitching shook a hat filled with equally-sized paper chits, each bearing the name of one of the ships, which combined carried 26,686 troops and all their necessary equipment. Division commander Major-General Guy Simonds drew three chits, which were considered lost to German U-boat torpedoes.

If all three ships were part of the fast convoy—carrying most of the division’s troops and those of 1st Tank Brigade—the outcome was particularly stark: vital equipment, such as 1st Brigade’s tanks could be lost, and sometimes as many as 1,000 infantrymen might be drowned or burned in oil-drenched seas.

Troops head for the invasion beaches aboard HMS Hilary

PRACTISE PRACTICE

Canadian troops conduct an exercise in England in 1942. They had seen little front-line action during the early part of the war.

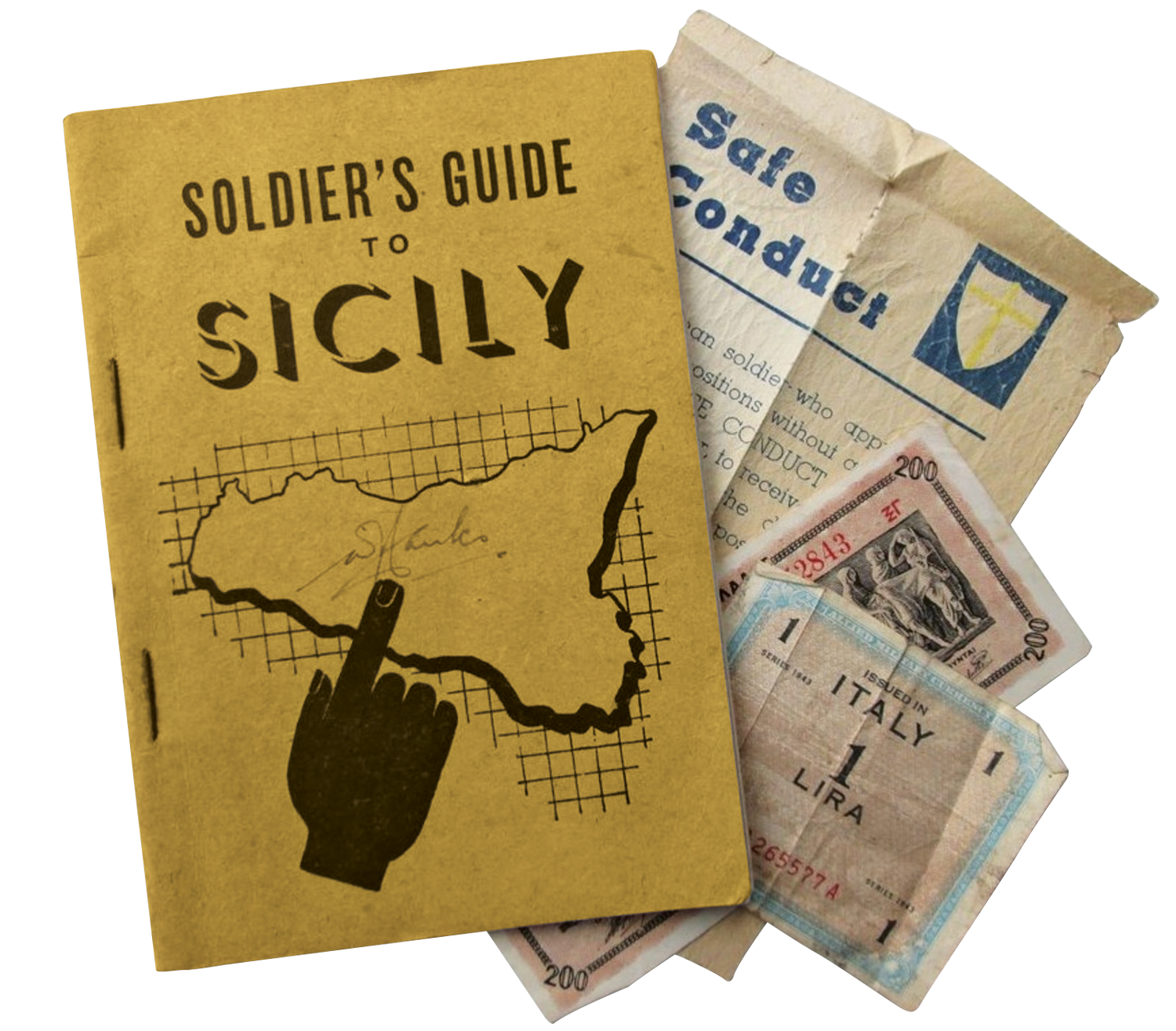

In addition to the epic plan—far longer than anything 1st Division would produce again during the war—the bulging bags yielded an informational treasure. Stacks of maps, air photos and intelligence pamphlets. A handbook, Soldier’s Guide to Italy, was issued to each soldier. Information on the country, culture, people and religion were augmented by sections explaining how to interact with civilians, with a list of useful words and phrases provided.

Sicily’s central and southern terrain was realistically detailed: mountains and hills falling directly to the sea or narrow coastal plains; the landscape one of bare treeless ridges, rolling hills composed of clay or soft rocks; difficult country with unstable slopes prone to landslides.

The summer climate would be hot and dry “with conditions very constant, the temperatures mounting by day and falling by night with monotonous regularity.”

Fighting in Sicily would be unlike anything the Canadian training in Britain had envisioned. Detailed operational plan aside, it was clear that improvisation would be a necessity. Aboard St. Essylt—in the slow convoy—Major Cameron Ware of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI) was the senior officer commanding about 320 soldiers who would be kept “Out of Battle.” They would provide a nucleus around which units could be rebuilt should disaster befall those attacking the beach. Ware had spent the past four days dutifully delivering the Operation Husky plan and, when they finally landed several days behind the assault battalions, he noted the soldiers were “puffed up about what they were going to be doing.”

After dinner on the evening of July 4, Ware was speaking with the ship’s captain on the bridge when a huge explosion ripped through the nearby converted passenger liner City of Venice. The convoy sailed on while designated rescue vessels rushed to the stricken ship’s aid. Thirty minutes later—the burning City of Venice just fading from sight—a torpedo slammed into St. Essylt. “You sure knew you had been hit by something,” Ware said later. “There was a great sheet of flame from the forward end of the boat.” In seconds, the bow holds crammed with ammunition were ablaze.

Crew and soldiers scrambled into lifeboats and paddled well clear of the soon fully engulfed ship. Miraculously, only one soldier and one sailor were lost from St.Essylt. Ten Canadians on City of Venice perished. The following afternoon, merchantman Devis, fell prey to a torpedo. Major Douglas Harkness, an artillery officer aboard, attempted to lead rescue parties to save men trapped in holds below, but was driven back by flames. Short of lifeboats, Harkness and many others drifted in the warm sea until rescued. Fifty-two Canadians died. By late afternoon on July 5, Simonds and Kitching faced the very calamity they had dismissed as statistically impossible. A total of 562 vehicles, fourteen 24-pounder guns, eight 17-pounders, and ten 6-pounder anti-tank guns were lost. Division historical officer Captain Gus Sesia wrote that “we lost great quantities of engineers’ stores and much valuable signals equipment.” Many precious wireless sets were gone as were 15 of 18 No. 9 Field Ambulance vehicles.

LUCK OF THE DRAW

Major William Ogilvie sketched the convoy en route to Sicily.

While some of the losses could be replaced from British supply bases in North Africa, most needed to come from Britain. Even what could be sourced from North Africa would take time to assemble and move to Sicily once the invasion beaches were secure and open to resupply vessels.

The disaster of losing these three ships meant the Canadians were going into the invasion seriously handicapped. Once beyond the beach, the infantry would have to march until replacement vehicles were found and delivered. But first, 1st Division must win the beach—code-named Bark West—and the possibility of the assault battalions being slaughtered on the sand was considered real—even likely.

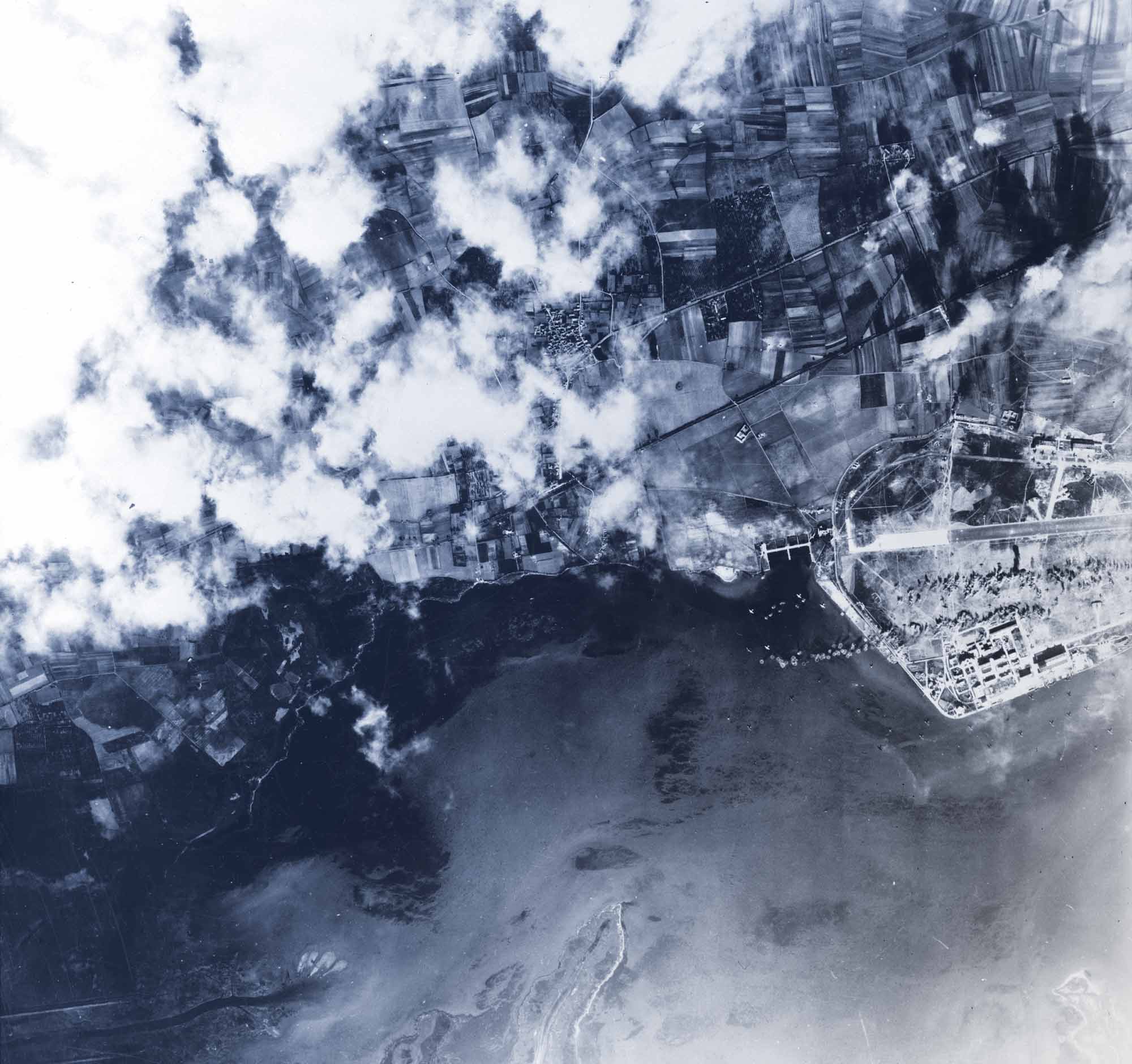

BIG SMOKE

The island of Pantelleria off Sicily is shrouded in smoke in advance of Operation Husky. As an enemy airbase, its capture was crucial to the invasion. The Allies bombarded the garrison, which surrendered and became a vital Allied station.

The early spring of 1943, there was no expectation that any part of the more than 200,000-strong First Canadian Army in Britain would join an invasion in the Mediterranean. Both its commander, Lieutenant-General Andrew McNaughton, and Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King had steadfastly insisted the army be kept whole for eventual participation in the inevitable cross-channel invasion.

McNaughton had explained the reasoning to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt during a March9, 1942, meeting in Washington. The Canadian purpose, he said, was to maintain “our foothold for an eventual attack on the Continent of Europe…There could be no question but that the war could only be ended by the defeat of Hitler and the only way of doing so was to attack him from the West.”

Sooner or later, a colossal invasion across the English Channel must come and the Canadians would play a pivotal role. Save reluctantly agreeing to fielding the major force for the disastrous Dieppe Raid, McNaughton had resisted any suggestion of diverting Canadian troops elsewhere.

IKE’S SICILY

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme commander of Allied forces in Europe, prepped a guidebook (above) for soldiers landing in Sicily

Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar, commanding First Canadian Army, engineered the debacles in Hong Kong and Dieppe, but he still successfully elevated Canada’s wartime role.

By 1943, however, McNaughton’s influence—even with the prime minister—was waning. At every turn, I Canadian Corps commander Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar undermined McNaughton. Not only did Crerar want McNaughton’s job, he also vehemently opposed keeping First Canadian Army intact.

Crerar was always open to sending Canadian troops into the fray. His influence had been instrumental in a Canadian contingent reinforcing the garrison at Hong Kong shortly before the December Japanese invasion overran the colony.

In 1942, he was at the forefront in getting 2nd Infantry Division tasked with leading the Aug. 19 Dieppe Raid.

Crerar was unrepentant about his role in the two debacles. With strong connections to both Britain’s chief of the imperial general staff, General Alan Brooke, and Canadian chief of general staff, Lieutenant-General Kenneth Stuart, Crerar easily convinced both that the time had come for some element of First Canadian Army to fight. He also had the ear of Canada’s defence minister, Colonel J. Layton Ralston, who agreed the army could no longer sit on the sidelines until a cross-channel invasion occurred.

Crerar and his supporters argued that the inaction was causing morale problems within the army and a decrease in operational efficiency. Training alone could not keep the men fit, well-disciplined and ready for combat. Brooke was keen to see a Canadian division committed to action to “provide an outlet [for] officers and men to gain experience.” He considered McNaughton’s “fanatic antagonism for employing any portion of the Canadian Forces independent from the whole” unreasonable.

Taking advantage of an October meeting with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Ralston bypassed McNaughton and asked for “active employment” of Canadian forces “at the first opportunity.” Within the ranks, morale was better than Crerar and the others portrayed. But there was growing impatience to see action. “We’ll never be readier,” wrote Lieutenant Farley Mowat of the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment, also known as the Hasty Ps, in his journal.

“Wet, cold and dreary, our spirits sank from day to day as we wallowed in the mindless ritual of barrack life. The real war was becoming increasingly chimerical…something to read about or hear on the BBC.”

Impatience to see the army fight gained momentum at home in early 1943. Newspaper editors, old soldiers and politicians of every stripe voiced their discontent. First World War veteran Colonel John A. Clark pointed to the deployment of U.S. troops in Africa “while Canadians soldiers are sitting idle in England. This constitutes the greatest disgrace of the present war.”

The Ottawa Citizen complained that all “other Empire troops have had battle experience…Only Canadians, among the Allied combatants have not been tried.”

SPENT SPIT

A damaged Spitfire of 417 Squadron in Tunisia (below) is cannibalized for parts during the spring of 1943.

WINNIE AND FRIENDS

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (top, centre) meets with Crerar, British Lieutenant-General Bernard L. Montgomery and others.

Opposition Leader Richard Hanson complained in the House of Commons that the country’s soldiers were having “it thrown in their faces that while Australia and New Zealand are fighting gallantly on the sands of Africa personnel of the Canadian Army are not there.”

On March 17, 1943, King abandoned McNaughton via a telegram to Churchill, asking that the Imperial General Staff send Canadians to North Africa. Churchill soon agreed. Brooke advised McNaughton on April 23 that the British PM had instructed that any forthcoming operation should include Canadians and sought government confirmation that this was acceptable.

Subject to Canadian government confirmation, Brooke instructed, that 1st Infantry Division and 1st Army Tank Brigade be tasked to join Operation Husky.

Prime Minister King quickly agreed, with the proviso that McNaughton must approve the invasion’s viability. On April 26, McNaughton signalled Ottawa that Operation Husky was “a practical operation of war.” He recommended “approval of Canadian participation.”

In fact, Husky was fraught with problems that at times threatened to unravel the whole venture. The Americans were lukewarm about Sicily, fearing it would distract from invading northwest Europe. But they also recognized their involvement in Operation Torch and subsequent fighting in North Africa to eliminate the Afrika Korps had overstrained resources to the point that such an invasion would not be possible until 1944.

U.S. troops board landing craft at Bizerte, Tunisia, for the invasion of Sicily.

Churchill and Brooke capitalized on this when advancing the Sicily invasion concept at the Casablanca Conference in January 1943. Benito Mussolini’s Italy was on the verge of collapse and Sicily provided a perfect springboard onto the peninsula. Although Churchill broached his belief that Italy presented the soft underbelly by which the Allies could advance into the Axis heartland via Austria, he refrained from pressing this concept too hard.

The Americans considered Sicily a destination in itself—one that could assure mastery over the Mediterranean Sea and provide a huge launching pad for long-range aerial bombardment of Italy’s industrial north, Austria, Hungary and even parts of Germany.

Churchill and Brooke accepted this argument, suggesting that Sicily’s fall might be sufficient to bring down Mussolini and yield an Italian surrender. Neither abandoned the springboard plan, but they could develop that later. First, they had to get American troops into Sicily. It was agreed that U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower would be supreme commander, but planning and overseeing the invasion’s execution fell to British General Harold Alexander.

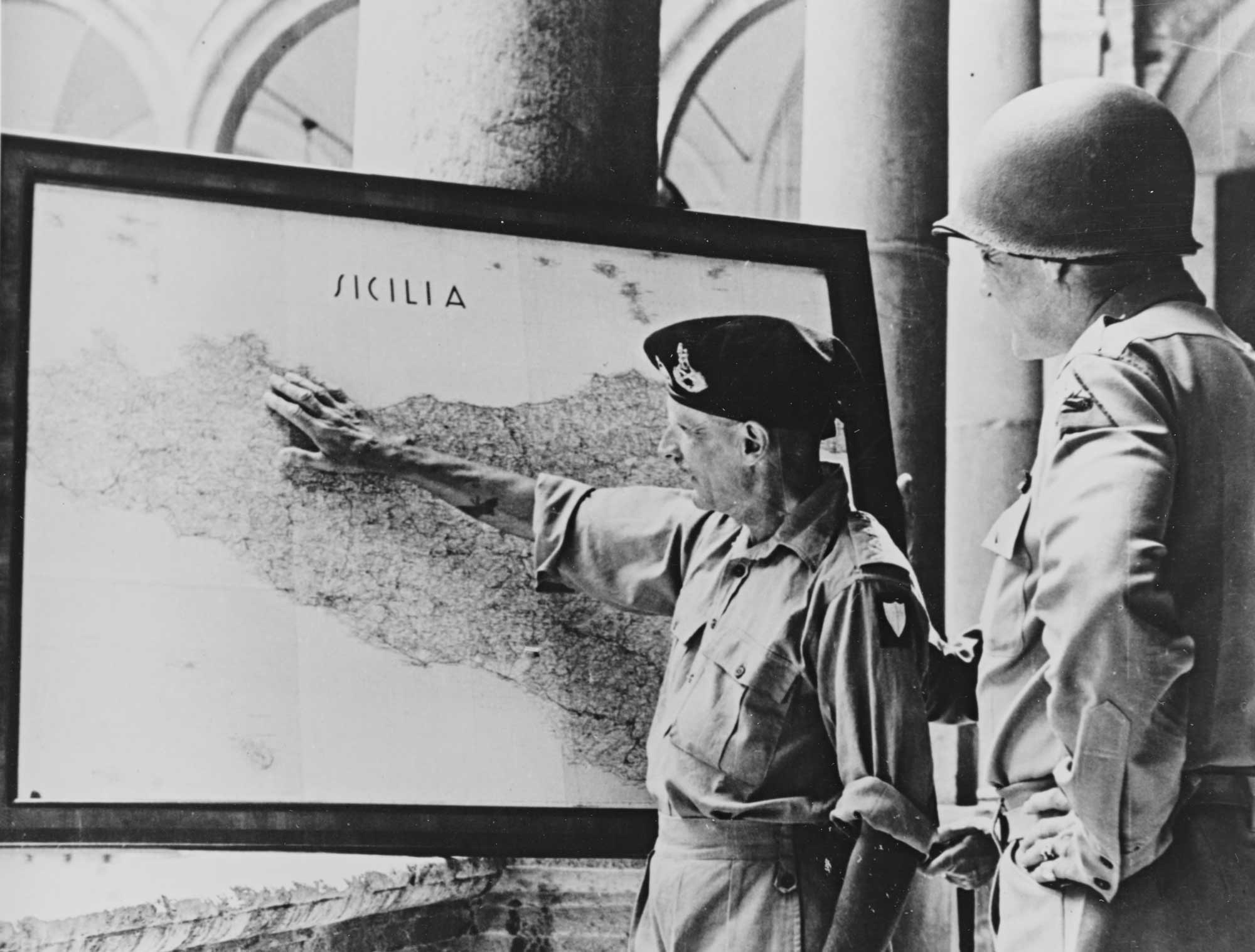

POINTING TOWARD PALERMO

Montgomery (above, left) and U.S. Army Lieutenant-General George S. Patton Jr. review a map of Sicily in the summer of 1943.

Everyone involved understood they were planning the most complicated amphibious invasion ever, involving various fleets sailing from North Africa, Malta, Britain and the U.S. Complex timetables must be strictly followed to ensure all forces arrived off the Sicilian coast at precisely set locations and times.

In Britain, the Canadian planners hit the ground running as soon as their role was approved. On April 27, 1st Division’s Major-General Harry Salmon presented a 10-page summary of their challenges. Salmon and his staff were still sorting through the document when they were summoned to the War Office in London. They found General Bernard Montgomery—flown in from North Africa—ready to put the Canadians in the picture. They would be folded into his British Eighth Army, which would land simultaneously alongside the American Seventh Army under General George S. Patton.

The following morning Salmon and a small staff boarded a Hudson aircraft outside London for a flight to more Eighth Army meetings in Cairo. A few hours later the plane was reported as having crashed over Devon. All aboard were killed. Chief of staff Lieutenant-Colonel Kitching immediately advised McNaughton, who swapped Major-General Guy Simonds from 2nd Division command to 1st Division.

SICILY LANDING

A William Ogilvie painting depicts the Three Rivers Regiment landing on Sicily’s Pachino peninsula on July 10, 1943

Major-General Harry Salmon of 1st Canadian Division was among those killed in a Hudson aircraft crash in England.

The English-born Guy Granville Simonds was raised in British Columbia, graduated Royal Military College, trained in artillery and established a reputation as a forward thinker—especially in the adoption of tanks in battle. With the war, his star had risen rapidly in various positions. At 40, he would now lead the largest Canadian contingent of troops so far in this war into combat.

Simonds had also drawn Montgomery’s attention, who much preferred him to Crerar for future command of First Canadian Army. He appreciated Simonds for his intelligence, but also his English mannerisms. Simonds admired Montgomery in return, even adopting his habit of wearing a tanker’s beret when neither had served in an armoured regiment.

After some wrangling and misstarts, Alexander presented a finalized plan on May 13 to the Combined Chiefs of Staff. Montgomery’s Eighth Army would carry out the main thrust by landing at Siracusa and driving up the eastern coastal plain through Catania to win the Strait of Messina—hopefully trapping large German and Italian forces before they could escape to the mainland.

Patton’s Seventh Army covered Montgomery’s left flank, taking towns and villages as they advanced, while Canadian and British troops drove up the eastern coastal plain.

Patton’s Americans would cover Montgomery’s left flank by advancing through the interior and liberating a series of little-known villages and towns. Alexander had feared a fiery protest from Patton, but uncharacteristically he offered no objections. The Canadians would form the left flank of Eighth Army and thus the juncture between it and Seventh Army. The plan was finalized just two months before the landing craft were to launch.

Operation Husky involved landing seven divisions—three American, three British and one Canadian, plus other units—onto 10 southern beaches across a 160-kilometre front. Preceding the sea assault, glider-borne paratroopers of British 1st Airlanding Brigade from 1st Airborne Division would establish an inland blocking force in front of Eighth Army while U.S. 82nd Airborne Division would parachute in to provide the same protection for Seventh Army.

To fill the gap between the Americans and the Canadians, Nos. 40 and 41 commandos of the British Special Service Brigade would land on the far western side of the bay where Bark West lay. July10 was D-Day. By day’s end, the Allies planned to have punched well inland from the beaches.

An aerial photograph of the invasion in progress.

Axis’ prisoners of war are marched along the beach on Day 1.

Author Farley Mowat at home in Port Hope, Ont.

In 1942, 21-year-old Farley Mowat entered officer training and soon joined the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment. In Sicily, Lieutenant Mowat served as a platoon commander. He marched across the parched countryside, fought numerous battles and was one of the officers leading the ascent of Monte Assoro.

Mowat maintained a personal diary. After Sicily, he continued as a platoon leader through the Battle of Ortona. Here, it

became evident that the prolonged combat and loss of comrades, such as Major Alex Campbell during the December 1943 fighting, had taken a psychological toll. As one soldier who knew him said, “Farley was too gentle a soul for soldiering.”

Author Farley Mowat as a young lieutenant with the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment. He served as a platoon commander in Sicily.

He served the rest of the war as the battalion’s intelligence officer (IO), a role requiring maintenance of the daily war diary. While many IOs considered this an onerous chore, Mowat’s daily entries—particularly when battles raged—were lengthy, meticulously detailed and well crafted. Even then, Mowat was thinking of a future as a writer, penning The Dog Who Wouldn’t Be while marching up Italy’s boot.

In 1946, Mowat was discharged. The next year he became a biologist in the Northwest Territories studying wolves and caribou. His first book, People of the Deer, was published in 1952. But Mowat never forgot his war experience.

He published The Regiment in 1954, drawing from both his personal and regimental war diaries. In 1979, he followed it with his memoir of the war up to the end of the Ortona battle, And No Birds Sang. Mowat died at 92 in Port Hope, Ont.

William Abernathy depicts the 12th Armoured Regiment’s approach to Assoro in July 1943.

Throughout Operation Husky’s planning, a continual worry was that Axis command in Italy would realize the threat to Sicily once the convoys bearing 181,000 troops aboard 2,590 vessels were detected.

The island was defended by some 200,000 Italian troops supported by 32,000 German soldiers and 30,000 Luftwaffe ground crews. About half the Italians served in four mobile infantry divisions, with the rest forming static coastal defence divisions and various support service units. Morale was known to be poor.

All the Italian units were under-equipped and suffered grave shortages, ranging from basic rations to munitions. Fortification of the beaches was patchy with many sections lacking minefields, obstacles, anti-tank ditches, pillboxes or dugouts. Beyond the beaches, little effort had been made to create in-depth defensive strength.

Sicily’s command structure was chaotic with the Germans chaffing at being under Italian authority.

HEAVY LIFTING

Allied forces had similarly bombed the nearby island of Sardinia and other locations in advance of the invasion.

Generalfeldmarschal Albert Kesselring commanded Nazi forces in southern Italy.

Given time to prepare, even the disorganized and ill-equipped Italians could potentially repel the invaders on the beaches. This would be particularly true if the Germans deployed more divisions to the island, which was sure to happen as their intelligence increasingly showed Sicily as a probable target. Both German and Italian intel had concluded the Allies were going to strike somewhere in the Mediterranean during the spring or summer of 1943. The only question was where? Sicily seemed obvious. But Corsica, Sardinia, and anywhere in Greece or other parts of the Balkans were also contenders, so all had to be reinforced.

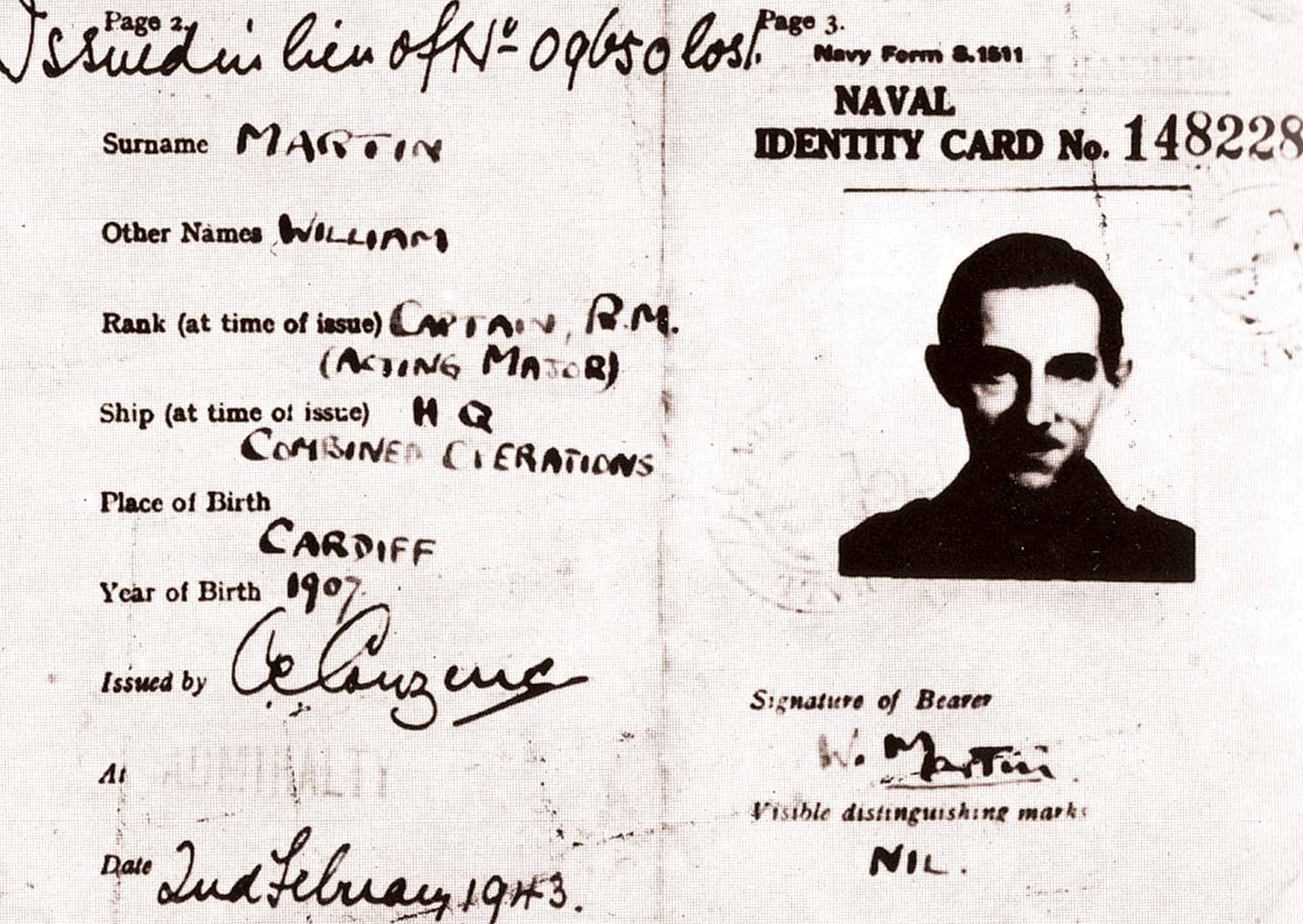

As Allied efforts to weaken and disrupt Sicily’s defences ramped up, the British believed the fact it was the target would become clear. To keep Axis intelligence guessing, a bizarre deception operation was launched in the early morning hours of April 30, when the corpse of a homeless man falsely identified as Major William Martin of the shadowy Combined Operation Headquarters in London was jettisoned from a submarine to wash ashore on the Spanish coast.

The false identity card that accompanied the corpse of “Major William Martin”, jettisoned by the Allies off the Spanish coast bearing misleading documents.

Chained to the body’s waist was a dispatch case bearing documents hinting at where the Allies were going to strike. Led to believe the officer had died in an air crash, German intelligence who acquired Martin’s documents from Spanish authorities puzzled their meaning.

Some documents indicated that Sicily was indeed the target, but only after Sardinia was seized. Others pointed to Greece with Sicily being a deliberate red herring to throw the Germans off. On May 11, the German naval staff declared it impossible to authenticate Martin’s documents.

WARTIME INTRIGUE

A German 2cm quadruple gun points seaward

Hitler and Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz agreed on maintaining Sardinia’s current defensive strength and that Sicily was unlikely. Two days later, however, the naval staff decided the documents were authentic and there would be a mock attack on Sicily followed by the invasion of Sardinia. Although the island was much smaller than Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica together could provide an excellent forward base for Northwest African Air Forces’ heavy bombers to strike anywhere in northern Italy.

Hitler, meanwhile, fixated on the bait that Greece or some other Balkan location was the target. With the Germans so uncertain about Allied intentions, Operation Mincemeat—as the deception was code-named—achieved success far beyond the wildest expectation.

BOMBS AWAY

Wing Commander Adolph Gysbert (Sailor) Malan of South Africa addresses RAF bomber crews in Tunisia prior to a night raid over Sicily.

To reinforce Axis confusion, the Allied bombing strategy ahead of Operation Husky included heavy attacks on both Sardinia and Sicily. Sardinian airfields had been subject to bombing since late 1942, but these increased in intensity through early 1943 to a peak on May 13, when a raid on the southern port of Cagliari reduced much of the city to ruins. Most of the population had already fled, so few civilians died. The northern town and minor port of Alghero was also bombed.

Systematic targeting of Sicilian ports and airfields had begun in February, but escalated on May 12 when 400 bombers struck Palermo. As May turned to June, Allied raids intensified. Between June 25 and July2, U.S. Northwest African Air Forces B-17 bomber groups struck 11 times, dropping more than 750,000 kilograms of bombs, while Royal Air Force Wellingtons attacking by night added to the destruction.

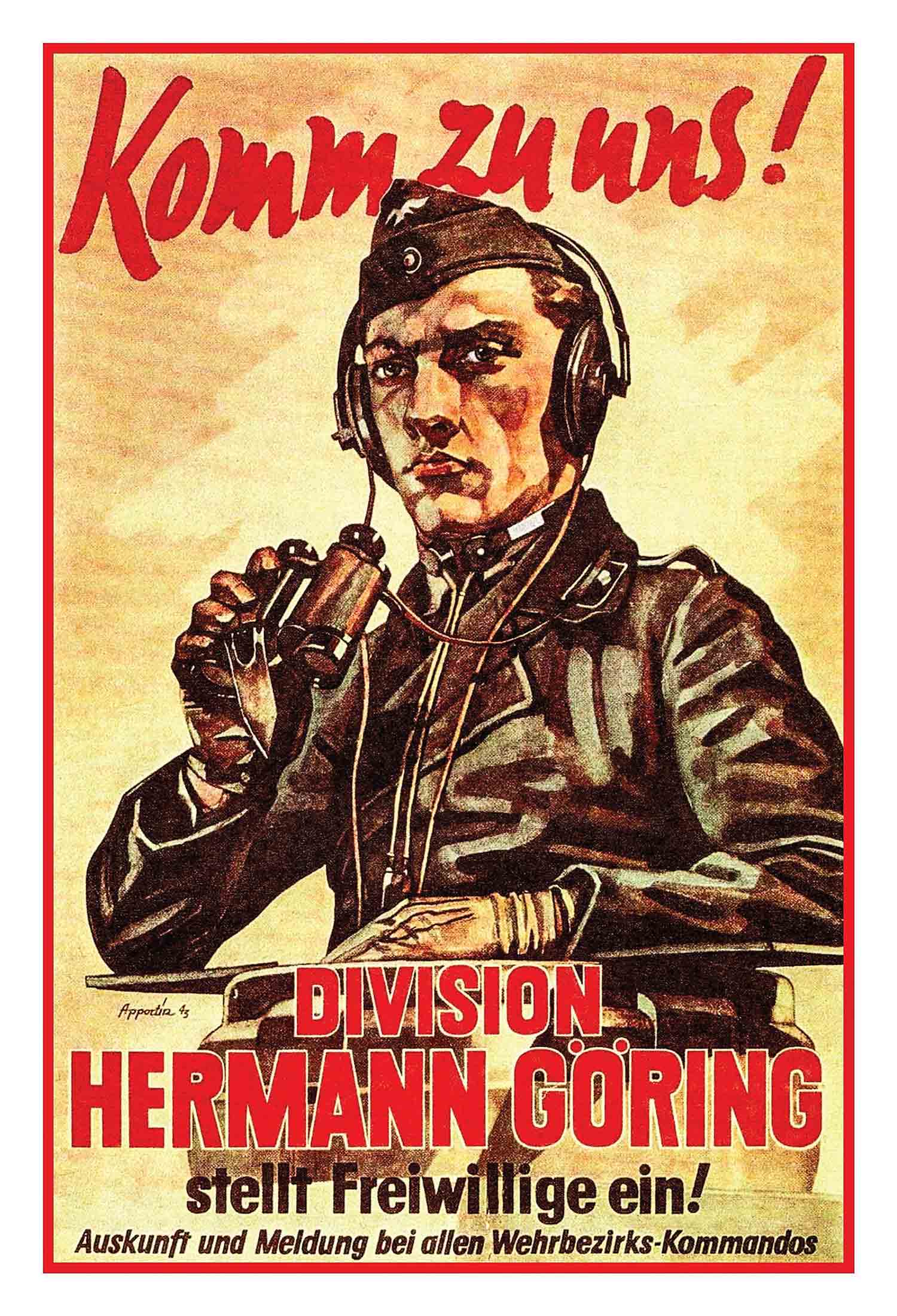

A recruiting poster summons volunteers to the Nazi cause.

Airborne troops in Sicily in 1943

Ports, railroads, highways, airfields and known military facilities were all targeted. So, too, were towns and cities. By the end of June, Catania was a ghost city—most of its population having fled the rubble of buildings, destroyed streets and mostly inoperable sewage, water and electrical systems. The civilians escaped into the woods on the slopes of Mount Etna—the massive volcano that loomed to the west of the city.

Convinced that Sicily was the real Allied target, the German commander of southern Italy, Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, beefed up the island’s defences on June 20 by deploying the Hermann Göring Panzer Division. It joined 15th Panzergrenadier Division. With no idea where an invasion force might strike, the Germans were held in the interior mountains, with plans to race them into the fray once landing beaches were identified.

RESIDENT AIRBORNE

Para field surgeons prepare for their first jump in January 1943 at a training centre in Montana.

HOT SHOTS

Spitfire pilots of 417 Squadron, RCAF, plan another operation in April 1943 from an airfield in Tunisia

As the Canadian and American convoys steamed past Gibraltar into the Mediterranean, Northwest African Coastal Air Force operations reached a feverish pitch, flying 1,426 sorties in the first nine days of July—574 of these occurred in a 48-hour period beginning the morning of July 7.

When the Canadian convoy closed to within 100 kilometres of Malta, the Canadian Spitfire squadron417 (City of Windsor) was among the fighters operating from the small island. Bomber forces, meanwhile, were hammering airfields and other targets in Sicily, Sardinia and southern Italy, day and night. Joining in these operations were the Wellingtons of Royal Canadian Air Force 331 Wing, made up of 420 (City of London), 424 (City of Hamilton), and 425 (Alouette) squadrons, all flying out of Malta.

On the night of July 9-10, Mother Nature threatened the entire venture with the heavy waves of one of the Mediterranean’s common storms.

Bombs drop on Monserrato airfield on the Italian island of Sardinia.

The convoys could only wait it out. In the British sector, four Royal Canadian Navy landing craft flotillas, each 12-vessels strong, were ready to carry troops and equipment to the beaches. The 55th and 61st Landing Craft, Assault (LCA) flotillas would deliver 231st Infantry Brigade to a rocky beach on Pachino peninsula’s east side. Meanwhile, the large 80th and 81st Landing Craft, Mechanized (LCM) would ferry vehicles and supplies ashore near Siracusa.

At 9 p.m., the waves and wind subsided. Signals declared the landings would proceed. Historical officer Gus Sesia noted the ships turning landward. “This is the final lap,” he wrote, “we shall invade Sicily.”

Bark West—a 7,600-metre-long narrow strip of sand with a gentle grade running from the waterline to a steep limestone ridge about five metres high fronted by low dunes—was invisible in the darkness. Behind the ridge lay salt marshes and ponds intermingled with vineyards, citrus orchards and grazing pastures. Several dried-up stream beds cut through the ridge to the sea, providing paths from the beach. About five kilometres inland, outside the town of Pachino with its population of about 22,000, was an airfield—the immediate Canadian objective.

DESERT SQUADRON

Spitfire Mk Vbs of 417 Squadron fly in loose formation over Tunisia on a bomber escort operation in April 1943.

Looking at the surface, the approaches to Bark West appeared straightforward. But a series of sandbars lurking underwater blocked direct access to much of it. The water between them was believed to be between 1.5- and two-metres deep, but that was only a guess. For this reason, the planners had decided the assault landing would be put in by infantry alone.

Two divisional brigades would land first—the 1st and 2nd—with 3rd Brigade forming the reserve. In the 2nd Brigade sector to the west, code-named Sugar, it seemed the sandbar was not continuous and the landing craft might be able to wiggle past. The eastern sector—Roger—was believed fully blocked.

Whichever the case, the assault battalions were expected to pile out of landing craft some distance from the shore and wade in. The restriction imposed on landing craft by the sandbars had led the planners to conclude that casualties gaining the sand would “be very high.”

Intelligence reports put between eight and 12 artillery pieces in range and many machine guns in positions overlooking the water. If “the enemy put everything into their defence” with the infantry wading sluggishly shoreward, a grim outcome was assured. And even having gained the sand, the Allies expected to be met by “wire entanglements and perhaps mines and booby traps to clear while under fire from enemy M.G. [machine gun] posts and pillboxes.”

In the end, hopes were pinned on the Italian coastal defence troops simply giving up. British XXX Corps commander Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese had cheerfully assured Simonds this would happen. “Once we have closed with him, he gives up,” he said. That aside, Simonds planned for the worst.

So long as each of the leading brigades could get the equivalent of one of its three battalions ashore, the drive for inland objectives would proceed. If “a whole brigade were destroyed” its action “would be carried out by the Reserve Brigade.”

Aboard ship, the troops were little aware of these higher tactical and logistical concerns. In heaving seas, the soldiers prepared to board landing craft. Aboard the troop ship Circassia, 2nd Brigade’s Seaforth Highlanders moved “very slowly in…one single line…up the gangways…along the dim corridors, up again to decks still higher till finally they reached the…boat deck,” Seaforth Padre Roy Durnford wrote in his diary.

Platoons moved to assigned LCAs. Each man filed past his officer onto the LCA “as it swung from its davits at the side of the ship. Here they would kneel on one knee with their rifles vertical in their hands until the craft had its full complement…in three rows.” After the officer boarded, the LCA was lowered to the heaving sea.

A German bomb dump is found at Comiso, Sicily, four days after Allied troops hit the beaches.

EAGLE EYES

German troops watch over a road from a forward observation post during the Allied drive to Messina.

Darkness cloaked the blacked-out invasion fleet, but not far distant, Sicily burned. Ninety minutes before the first landing craft headed for shore, flights of medium bombers had rained bombs on the defences inland. In the Canadian sector, Pachino, the airfield and its defences, Maucini and Ispica were badly battered. “A dull red glow suffused the sky…and we knew…Pachino was ablaze,” Durnford recorded.

The LCAs bound for Bark West tossed about like corks. Seaforth Sergeant Jock Gibson saw every soldier and boat crewman on his LCA throwing up. Years spent on West Coast tugboats left him unphased, but he worried his platoon would be unable to fight because of seasickness.

From another LCA, Corporal Felix Carriere of the PPCLI saw bombs exploding ahead. The Italians defending the beach were firing off flares and anti-aircraft tracer lashed at the bombers. The British monitor ship HMS Roberts blasted away with its heavy 15-inch guns and was immediately joined by the guns of more naval ships. Remembered Lieutenant Farley Mowat: “cataclysmic thunder overwhelmed our world.”

Italian soldiers mount resistance in Sicily.

It was about 1:30 a.m. when the LCAs carrying 2nd Brigade headed for Bark West. As the small craft disappeared into the darkness, the soldiers of 1st Brigade waited impatiently for the arrival of larger Landing Craft, Tank (LCTs) loaded with amphibious trucks known as DUKWs (known colloquially as ducks) that three of the four companies of the two assault battalions were to board to get across the sandbar and then into shore. Badly delayed, the LCTs were not fully underway until 4 a.m.

By then 2nd Brigade was already on the sand. Mercifully, the seas moderated as the LCAs entered the bay at about 2:30. The LCA pilots tried to use burning Pachino to steer by to assigned landing points, but the shore was so dark that picking out any details proved impossible.

Many of the PPCLI craft ground onto the sandbar. Piling off the lowered front ramp, men plunged into the sea. Where it was waist deep the soldiers plodded forward, but some platoons went in over their heads. Abandoning weapons and equipment, these men swam to the sand.

Seaforth Gibson’s LCA also butted up on the sandbar. Wearing Mae West life jackets, he and his men swam until they could walk through the surf. As Gibson came up on the sand, he saw exposed land mines lying all around before a tangle of barbed wire. Gibson spotted a small beached fishing boat and before it was a gap in the wire presumably left for the fishermen. His platoon led the way through the gap.

Nearby, ‘A’ Company’s Captain Sydney Thomson found the wire so tautly strung that the men could step on the top strand and walk over. There was little incoming fire and only a few casualties were suffered before the Italian guns fell silent. Realizing the brigade was ashore with initial objectives won, Thomson fired a flare at 3 a.m. signalling success. The feared disaster on Bark West was not to be.

A German tank lies in ruin at Biscari.

As Leese had assured Simonds, the Italians opted not to fight. Everywhere men in ragged uniforms surrendered, while others melted into the night. Many were Sicilians who simply went home. Having managed to get ashore just before dawn, 1st Brigade’s Hasty Ps and Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR) advanced on Pachino and the airfield.

Scattered resistance from the batteries protecting the airfield was quickly crushed and the main Canadian objective was in hand by 6 p.m. The RCR’s war diarist boasted that the battalion “was the first to capture an airfield in Sicily.”

Dogged more by the heat than resistance, Captain Ian Hodson noticed his men shedding extraneous equipment. “Without instructions…we stripped down to the very basic necessities to become mobile and…conserve energy. We all recognized that we had a great deal to learn, but we had taken a first step toward becoming good soldiers.”

READING BETWEEN THE LINES

Captain Angelo Thomas Sesia and Major C. Whitney Gilchrist of the 1st Canadian Division discuss the impending attack aboard HMS Hilary.

TIGHT QUARTERS

A British soldier inspects a captured Italian pillbox in the Pachino area.

On July 13, General Bernard Montgomery ordered 1st Division halted in assigned rest areas and announced he would visit the troops the following day.

Monty’s inspections were tightly scripted. He tried to avoid leaving men standing by keeping to a tight schedule while moving from one inspection to another. The men were to wear shorts, shirts, steel helmets and web belts. Boots could go unpolished, the dust rendering this pointless.

If all went as planned, the soldiers reached their assigned position only shortly before Monty arrived in his open car. Forming square, the troops gave him a general salute he returned. Monty then yelled for them to gather round, so they could hear him. “Sit down, boys, and take off your helmets. I want to see your good Canadian faces again…I hope you are enjoying it here. They tell me it looks just like Canada.” This brought guffaws, precisely as Monty intended.

Monty said he was glad to have the Canadians in his army and they had so far done “a splendid job.” But, he cautioned, “that we are going to be faced with difficult country and soon you will be running up against the Germans…[who] are tough, very tough opponents. But I am confident that you can master them.”

Seaforth Highlander Private Richard Latimer thought Monty was offering predictable senior officer clichés. “Yet somehow that wiry, ordinary little guy in his baggy pants…and the famous black beret…exuded confidence and it could not help rubbing off on us.”

This was precisely Monty’s intent.

THE SPARTAN GENERAL

Eighth Army commander Bernard Montgomery could be difficult to get along with but proved to be one of most prominent and successful British commanders of the Second World War. Monty addresses Canadian troops on the Sicilian coast.

The day after the assault on Sicily began, the Allies had won a firm toehold beyond every beach. Each landing had gone well. But not everything was smooth sailing.

The airborne operations proved disastrous. About 5,000 paratroopers had been flown from Tunisian airfields in the largest such operation to that time. Poor navigation, high winds and heavier-than-expected anti-aircraft fire badly scattered the flights. Pilots released the British 1st Airlanding Brigade far out to sea. Some 60 gliders crashed and 252 of the 2,075-strong unit drowned. Only 12 gliders reached the assigned landing zone with the rest strewn across about 50 square kilometres. Operating on their own initiative, small groups of paratroopers marched across country to seize their objectives.

The Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry makes its way through barbed wire en route to Adrano in August.

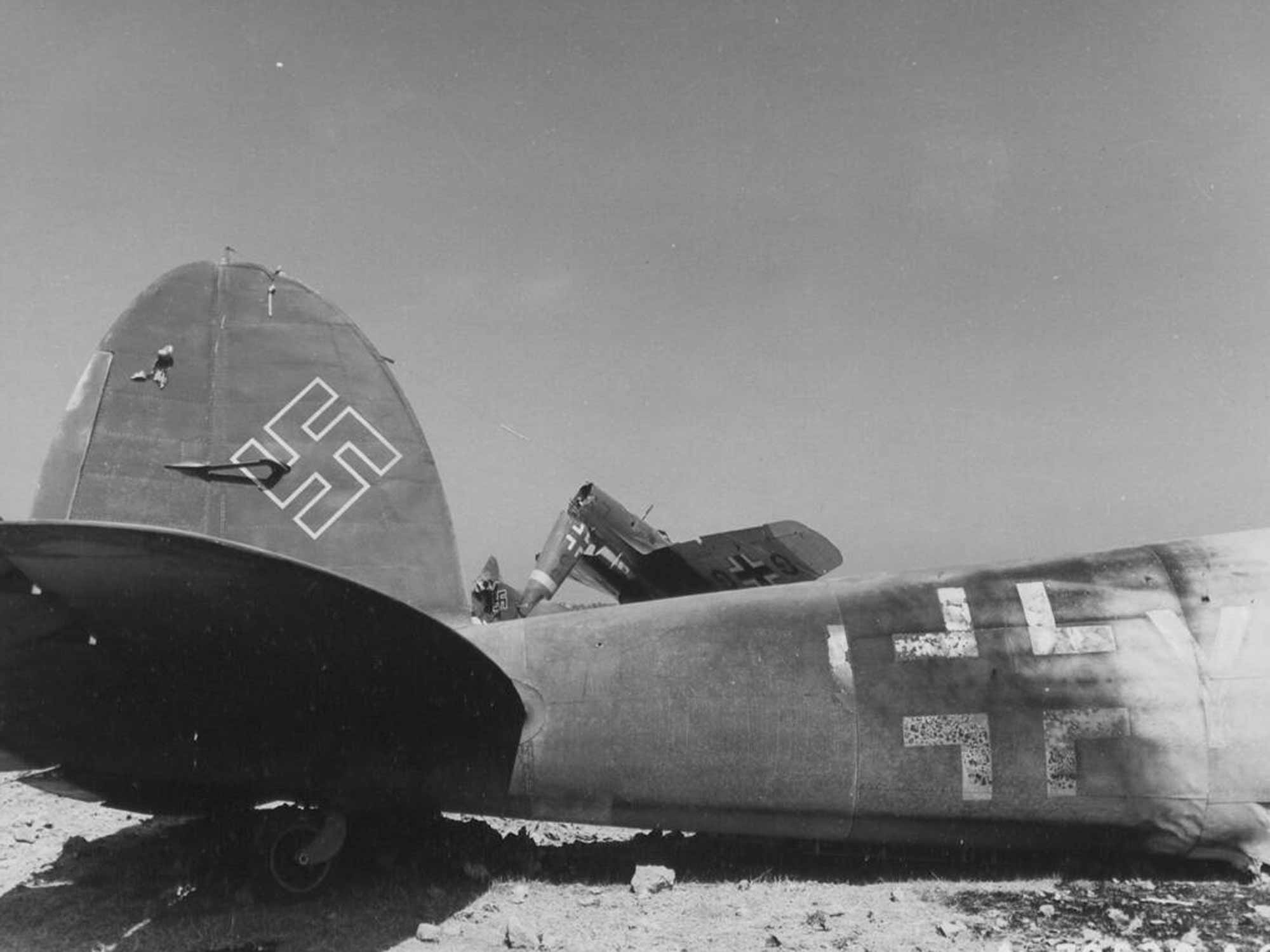

The U.S. 82nd Airborne Division was also scattered over about 75 square kilometres. Again, individual small units saved the day by pushing through to objectives or erecting ad hoc roadblocks they defended so fiercely that an attempt by the Hermann Göring Division to break through to the American beaches was prevented. Operation Husky had achieved stunning tactical surprise. Kesselring only learned on July 9 that the convoys were all vectoring toward the southeast corner of Sicily. At that point, it was too late to move the German divisions from their inland holding positions—he feverishly hoped the Italians would vigorously defend their homeland. On July 11, with the invasion force pouring men and equipment ashore, the Seventh and Eighth armies advanced inland. The Allies kept expecting stiffening resistance, but it failed to materialize.

MEET UP

British and Canadian troops meet in Caltagirone after entering the town from opposite sides.

Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds is widely acknowledged as one of the war’s best Canadian generals.

After holding in place through the morning to meet a possible counterattack, Simonds sent 2nd and 1st brigades marching, with 3rd Brigade following in reserve. Second Brigade advanced on a road running through Ispica, Modica and Ragusa, while 1st took a parallel route further inland that proved to be only a series of “rocky trails” that were almost impossible to discern because of the thick dust kicked up by the marching troops.

By mid-afternoon, the Loyal Edmonton Regiment, the Eddies, had tromped nine kilometres along the good road to where it curved up steeply to Ispica—perched on top of a 46-metre-high rock cliff. They expected the town would be heavily defended, which seemed to be the case when a patrol edged into the outskirts and was driven back by a flurry of shots and grenades flung out of houses.

LONG AND WINDING ROAD

Canadian tanks make haste along a mountain road on July 28, 1943.

Canadian infantry march near the city on July 12.

Lieutenant-Colonel Jim Jefferson called down a salvo from the British cruiser, HMS Delhi. When the smoke from the 5-inch shells cleared, he sent an Italian civilian to tell the defenders to surrender or face more fire. At 2:50 p.m., Jefferson cautiously moved a company into the town and about 200 Italian troops surrendered.

The Eddies moved on, and by the time the PPCLI arrived a few hours later, the citizenry was waiting. “Many natives stood in the streets waving and clapping,” the regiment’s war diarist wrote. “Wine and fruit were passed out to the troops, the hatred of Mussolini and the Germans being expressed time and again.”

MODICA MOMENTS

Enemy prisoners (this image) are moved to the rear on the road from Modica.

As the Canadians advanced through villages and hamlets, they repeatedly found the local Fascist authorities had fled and what troops of 206th Coastal Defence Division they encountered were eager to surrender. These soldiers were always “bedraggled and frightened,” either barefoot or wearing “cracked shoes.”

On July 12, a 13-man gaggle of RCR soldiers from the anti-tank platoon and mortar platoon got separated from the main force and were fired on by an artillery position covering an intersection in front of a small church. The only officer with the men was Lieutenant Sheridan (Sherry) Atkinson. He was mulling what to do when a Canadian officer on a motorcycle roared up.

The Italians fired a machine-gun burst and the officer piled into a ditch alongside Atkinson, who was startled to realize the man was 2nd Brigade’s Brigadier Christopher Vokes. Handing Atkinson his Thompson submachine gun, Vokes thundered off on the bike and summoned a British Forward Observation Officer (FOO) to provide support.

Advancing behind a barrage, the 13 Canadians rushed in and took the surrender of 79 Italians equipped with seven artillery pieces, one anti-tank gun, five machine guns, and several Fiat trucks bursting with supplies. The Canadians suffered no casualties.

DOWN AND OUT

German planes lie wrecked at an airfield near Catania in August

Atkinson was overseeing the disarming of these troops when the mayor of nearby Modica trotted up in a garish uniform and announced that he wanted to surrender his town. Atkinson mounted his motorcycle and Lance Corporal Verne Mitchell hopped on the back. Motoring into the town, the two Canadians were greeted by cheering civilians, then in the main square by about 900 Italian troops lined up in three ranks with weapons neatly stacked.

While one of the bigger bags of prisoners, the capitulation of Modica was similarly repeated in other places—resistance was scant and usually confined to an initial flurry of firing followed by rapid surrender. There were exceptions.

On the night of July 14-15, an Eddie platoon of ‘C’ Company suffered the battalion’s first casualties of the war when it was fired on while riding aboard Shermans of the Three Rivers Regiment. The tanks quickly smashed the Italian machine-gun post with 75-millimetre fire, but three Eddies were killed and another six wounded.

William Ogilvie depicts a mule train’s departure from the area near Agira that month.

The Allies expected that sooner or later the Germans would show up and that moment came on July 15 as the Hasty Ps closed in on the large town of Grammichele.

A lead force of carriers and scout cars was followed by part of ‘B’ Company riding on three tanks. The rest of the battalion was about four kilometres behind. As the lead force entered the town’s outskirts, it was ambushed by the 4th Hermann Göring Luftwaffe Regiment, which fired several self-propelled guns mounting four-barrelled 20-millimetre guns. The force’s three carriers were set alight, one man was killed and several others suffered burns.

BENITO BEGONE

A portrait of the then recently ousted Italian prime minister Benito Mussolini, pierced by bullet and bayonet, hangs on the road from Messina to the ferry linking Sicily to mainland Italy on Aug. 17, 1943.

‘B’ Company fought its way into the town and a wild fight ensued, less controlled by officers than by groups of men just charging the enemy. The Hasty Ps had trained to break such ambushes by going straight into the face of the fire. They did so. As the rest of the battalion arrived, the battle broadened with supporting artillery weighing in until the Germans faded away at noon.

That evening, Simonds received new orders from Montgomery. The British XIII Corps, who were supposed to be leading the advance on the Eighth Army right through Catania had been checked short of the city. It was now “important to swing hard with our left,” so the Canadians must “push on with all speed” on a line that would take it into the mountains west of Etna. “Drive the Canadians hard,” Montgomery urged Simonds.

SICILIAN PARLEZ

French-Canadian troops converse with French-speaking Sicilians after the liberation.

From being on the sidelines of Eighth Army’s advance, the Canadians were now making the main thrust in an advance directed north to the Strait of Messina. The strait was the key to victory, for the Germans could only escape Sicily by ferrying troops across their narrow waters.

Montgomery did not particularly expect the Canadians to reach the strait. He instead wanted their advance to draw Germans away from his still preferred line of advance north through Catania on the east coast. Forced to thin out their strong blocking operation in front of XIII Corps to meet the Canadian threat, Montgomery hoped to be able to break past Catania and quickly reach Messina—possibly trapping the Germans and eliminating them on the island.

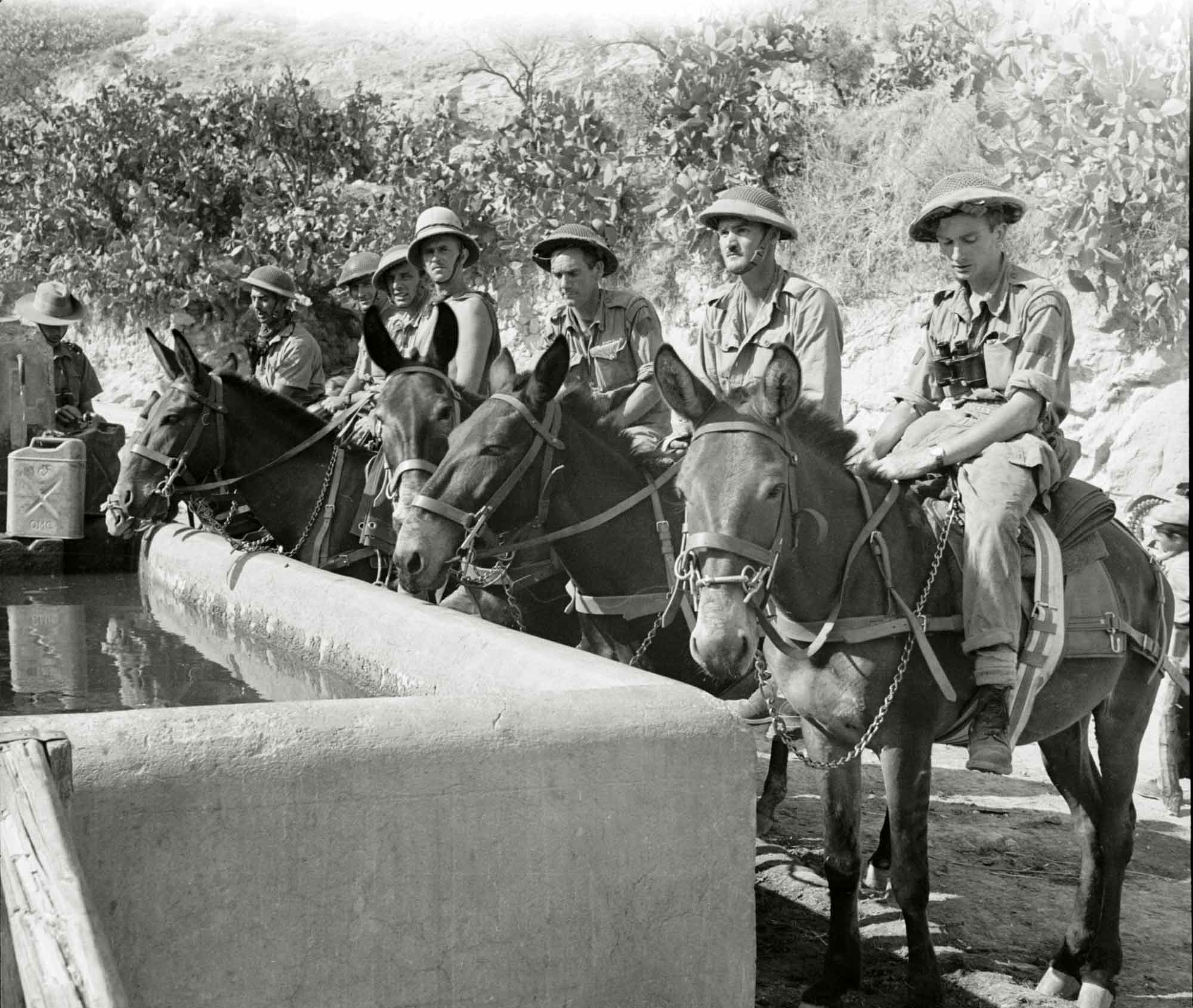

Although Simonds immediately set to driving “the Canadians hard,” advancing rapidly was no easy feat. Because of the transport lost at sea, the infantry was still largely forced to march—often bringing along vital supplies of food, water, medical supplies and ammunition on small carts pulled by donkeys and mules purloined from local farms along the way. Captured Italian military trucks and other vehicles were also pressed into service.

Pioneers of The Royal Canadian Regiment water their mules near Regalbuto on Aug. 4.

CHOW LINE

William Ogilvie’s watercolour depicts Canadian troops at the kitchen in Agira.

The heat, which only intensified the further inland the troops marched, slowed progress. Men were also falling ill to dysentery, malaria, heat exhaustion and dehydration. Instructed not to drink untreated water from wells or what few streams were not dried out, the soldiers had to choose to risk either dehydration or contracting dysentery or other illnesses by ignoring orders.

Availing themselves of fruit and vegetables carried the same risks. Despite having been given the anti-malarial drug Mepacrine, some men were contracting the disease because they faked taking the daily dose due to a rumour that it caused impotency.

The 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade Headquarters draws water from a well near Assoro in July 1943.

As the long lines of troops marched through the dust, they entered an ever more rugged landscape of steep mountains linked by spiny ridges. To the east, Mount Etna hulked—its summit often cloaked in cloud or smoke. The roads into the shoulder mountains of Etna increasingly deteriorated. It was ideal country for the defence—every ridge, mountain and hilltop town presented an obstacle the Germans skillfully used to block the Canadian advance.

On the Canadian left flank, meanwhile, General Patton had been chaffing at playing second fiddle to the British-Canadian operations. “Monty is trying to steal the show,” he wrote on July 14. Three days later, Patton met Alexander and proposed splitting Seventh Army. While leaving a smaller force to cover the Eighth Army, Patton would race the bulk of his army to the island’s largest city of Palermo rather than continue to aim toward Messina. Alexander reluctantly agreed.

The fact that Allied intelligence had determined the line of the German withdrawal was directed toward northeastern Sicily was irrelevant to Patton. Palermo was of no strategic value, but Patton was obsessed with the idea of being the city’s liberator. As U.S. General Lucian Truscott of the 3rd Infantry Division put it, Palermo drew Patton “like a lodestar.” And taking it in an armoured sweep across Sicily would establish a reputation for daring and dash.

Swinging away the bulk of Seventh Army eased the pressure on the Germans and enabled them to divert troops into the line of the Canadian advance.

Just how tough the advance into the mountains was going to be was evidenced on July 16 as 2nd Brigade approached Piazza Armerina. The town of about 22,000 atop a 720-metre summit was considered no more than a whistle stop for the brigade’s advance on the towns of Enna and Valguarnera.

GAINING GROUND

Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph Marston Crowe and Major John Henry Pope of The Royal Canadian Regiment read a map in Piazza Armerina, Sicily, in July 1943.

But as the column descended into a valley to approach the town, the heights to its south erupted with fire from machine guns, mortars and artillery. A nine-hour battle ended at 9 p.m. with signs that the Germans were withdrawing from the town. The Eddies, who had been leading the brigade column, suffered 27 casualties while the Three Rivers tankers lost 11 men killed and wounded.

The next day 2nd Brigade began cautiously clearing Piazza Armerina while Simonds brought 3rd Brigade out of reserve to take over the advance on Enna and Valguarnera. At the juncture of four main roads running from east to west and through which most traffic moved northward from the island centre, Enna was the primary objective.

Why Piazza Armerina had been so stiffly defended became clear when the Canadians discovered it had been headquarters for the Italian XVI Corps—yielding almost 250,000 litres of fuel and other supplies the Germans had not had time to destroy.

Enemy vehicles burn as the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry advances at Valguarnera, Sicily, on July 20.

From Piazza Armerina to Enna was about 30 kilometres and Simonds expected 3rd Brigade to reach it no later than sunset on July 17. Topography again worked for the Germans as the road to Enna and Valguarnera climbed through a narrow mountain gap called Portella Grottacalda, which the Germans had heavily fortified.

By the end of the day on July 17, the brigade was stuck in place before it. That evening the Royal 22e Régiment—the permanent force Van Doos—were sent to fight through the pass. Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Paul Bernatchez cobbled together enough trucks and carriers for the Van Doos to mount up.

Tarpaulins stripped off the trucks, the men knelt in the beds with guns bristling. At less than 10 kilometres per hour, the convoy crept forward with the carriers leading. No sooner did the convoy start climbing into the pass than machine guns laced it with fire.

As the Van Doos spilled out of the trucks into the ditches, one exploded in a fireball. Caught in rocky ground sparsely covered in shrubs, the Van Doos scattered into what cover they could find and fired back at the hidden Germans.

Out front, ‘B’ Company’s No. 11 Platoon, commanded by Lieutenant Pierre-Ferdinand Potvin, was pinned down. Potvin knew the platoon had to move or it would be annihilated. Only two sections of six men each, his seven-man command team and a three-man Bren gun team had any chance of moving, and then only forward.

AWAITING THEIR FATE

Enemy prisoners await orders from their Canadian captors at Agira.

He sent one section to provide flanking fire, then led the other 13 men up a near-vertical slope toward the nearest machine-gun post. Managing to approach undetected, Potvin’s small force overran the position, then turned their fire on Germans below them.

Potvin deployed his 2-inch mortar team to drive off a self-propelled gun and led a charge that cleared an adjacent house. Almost out of ammunition, the platoon fell back on the carriers. Potvin’s actions created such havoc on the German right that the Van Doos were able to use the time to dig in and await 3rd Brigade developing another plan for winning the pass. Potvin received a Military Cross for bravery.

To break the impasse, Simonds advanced the rest of 3rd and 1st brigades across a broad front to outflank the Germans with a cross-country push to Valguarnera. What ensued was a series of battles fought by individual battalions seldom supported by either tanks or artillery. The landscape was mostly too rugged for tanks, wireless reception was spotty, companies tended to get lost in the jumbled terrain and firefights were short and fierce.

Infantrymen of The Loyal Edmonton Regiment, aboard a Universal Carrier, take shelter from the Mediterranean sun at Valguarnera, July 17, 1943.

Suddenly six trucks, each with 20-30 Panzergrenadiers aboard, rumbled along below their position. At a range of about 100 metres, the Hasty Ps unleashed a torrent of rifle and Bren-gun fire. Trucks disabled, the Germans could not escape. ‘A’ Company’s Captain Alex Campbell, firing a Bren gun, led a charge down the slope to the trucks—his bullets killing 18 of the 80-90 Germans who died. Eighteen others were taken prisoner.

The Germans responded quickly to the ambush with a grenadier battalion pouring out of Valguarnera. After beating back repeated assaults, the Hasty Ps were running out of ammunition and so leapfrogged the two companies back into the rugged terrain in a fighting withdrawal.

By the night of July 19, Valguarnera was taken and the pass open. The two 104th Panzergrenadier Regiment battalions had suffered heavily with 500 men either killed or taken prisoner. Canadian casualties were 145, with 40 fatalities.

“The slaughter was terrific and only remnants got away,” Simonds boasted. Kesselring reported on July 20 that the grenadiers believed the Canadians were trained for fighting in the mountains. The grenadiers were calling them “mountain boys.” High praise for soldiers who had received only eight days training in cliff climbing at Sussex by the Sea.

Enna was quicky liberated, as the Germans pulled back to Monte Assoro, the hilltop town Leonforte and a connecting ridge north of the Dittaino valley. Assoro and Leonforte were the linchpins—take them and the ridge was indefensible.

Seizing the 906-metre-high Assoro fell to the Hasty Ps. A switchback road led through the village of Assoro on the western slope to the summit where a ruined Norman castle stood. Trying that route would surely get the battalion butchered. Sutcliffe and intelligence officer Captain Maurice Herbert (Battle) Cockin were developing a plan to assail the mountain’s southeast cliff face when a German 88-millimetre shell struck near them. Sutcliffe died immediately and Cockin soon after.

ENEMY ENGAGED

Members of The Carleton and York Regiment take stock during an attack on a German position.

The 7th Battery, 2nd Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, fires a 25-pounder gun at German positions in Nissoria in late July 1943.

Brigadier Chris Vokes commanded the 2nd Canadian Infantry Brigade during the invasion of Sicily.

Major Lord Tweedsmuir led the battalion toward the mountain on the evening of July 20. Reaching the base undetected, a 65-man volunteer assault company led the climb. Lieutenant Mowat was one of the five officers. They clambered straight up the cliff as a false dawn tinged the eastern sky.

Assoro had been carved into 47 overgrown terraces. One man boosted to the top then pulled another up. Every soldier helped comrades to get everyone up to the next terrace. Not a man slipped, no weapons or ammunition clips were dropped, in an agonizingly strenuous effort that Mowat later described as a night when “each man…performed his own private miracle.”

Just shy of dawn, the lead climbers burst onto the summit and swept the German garrison off. The rest of the battalion arrived minutes later. Everyone dug in and a grim fight ensued to beat back repeated counterattacks until relieved by a force of 48th Highlanders on July 22. Canadian correspondent Ross Munro described Monte Assoro’s capture as the Sicily campaign’s “most daring and spectacular” action.

On the opposite flank of the German line, another major action played out in Leonforte. The oblong-shaped town of 20,000 was about a kilometre in length. At 9:30 p.m. on July 21, 2nd Brigade’s Loyal Eddies fought their way into the streets.

Due to its size, Lieutenant-Colonel Jim Jefferson was forced to commit all four companies to a bitter house-to-house fight he was unable to control. Counterattacked by combined infantry and armour, Jefferson ordered a retreat. But he and about 100 men were unable to escape. Thirty of these men were with Jefferson in a building’s wine cellar, while the other soldiers fought elsewhere in small groups or even individually. Jefferson passed a note and cash to 10-year-old Antonio Giuseppe pleading for a relief column.

By luck, the boy reached Brigadier Vokes who mounted a PPCLI force on tanks with four 6-pounder guns of 90th Anti-Tank Battery towed by trucks and rushed it toward the town. To reach Leonforte required crossing a bridge that engineers had erected during the night under fire. The first attempt at about 6:45 a.m. was thrown back, but a second effort at nine o’clock won through and 45 minutes later the column reached Jefferson.

ENEMY ENGAGED

Members of The Carleton and York Regiment take stock during an attack on a German position.

By nightfall on July 22, Leonforte was taken. The 275 casualties in the preceding three days were the division’s most costly in Sicily.

Although beaten, the German recovery was agile—pulling back to a new line of defences in hills guarding the western approaches to Agira—another town standing on a 700-metre hilltop. From Agira a main road ran through Regalbuto to Adrano in the foothills of Mount Etna.

Montgomery now ordered the main Canadian advance to follow this route, while 3rd Brigade advanced east in the Dittaino valley and would then take a road running north to Regalbuto.

At the same time, with Patton having concluded his triumphal parade in Palermo, Montgomery proposed the U.S. Seventh Army advance by the good highway on Sicily’s north coast to Messina and close the German escape route there. The Sicily campaign was entering an inevitable end-game the Germans could not win.

Yet, to evacuate their divisions across the strait they had to maintain an ever-shrinking defensive perimeter for as long as possible. They would not give up Agira easily.

MILITARY MEDICINE

Canadians bring in the wounded in Catania.

A Sherman tank makes its way among Canadian troops in Sicily.

Nursing Sister Constance Browne of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps at Leonforte, Sicily, on Aug. 7, 1943.

For much of the campaign, Canadian infantry was forced to march, lugging weapons and other gear with them because of the vehicles lost when the three ships were torpedoed en route to the invasion. They called this being “on shank’s mare.”

One anonymous soldier of the 48th Highlanders’ ‘A’ Company described the experience of the march on July 11-12: “It was soon terrifically hot. We marched and marched. It grew terrifically dusty. It was dust, dust, dust. We marched and marched. Our tin hats would fry eggs. We marched. Men collapsed from heat exhaustion. We marched, counting one, two, three, four. Some were crying (literally) from blistered feet. We marched. Some had dysentery. We marched, one, two, three, four. We stopped for one hour for lunch. There was no lunch but a biscuit. We marched.

There were terrible sun blisters. We marched. About 1400 hours we fell out. We were to rest. We did, but we marched to the heat in our sleep.”

Marching not far from the Highlanders, the Hasty Ps also suffered. The heat was unlike anything the men had previously experienced, wrote Lieutenant Farley Mowat in the regimental history. When their column stumbled into the brigade rally point, men “lay in the ditches, stupefied, and simply waiting. In two and a half days they had fought a battle and then marched almost fifty miles. It was not credible that they could do more.”

But more they must do and did, ultimately marching more than 200 kilometres to victory.

DUST DEVILS

Canadian troops trudge through ankle-deep dust along a Sicilian road on July 31, 1943.

On July 23, Simonds and his artillery commander Brigadier Bruce Matthews used the summit of Monte Assoro to observe the approaches to Agira. A gunner by training, Simonds believed 1st Brigade could advance behind a creeping barrage across open ground that lay between Nissoria to the west and Agira.

More than 150 field- and medium-artillery guns and squadrons of Kittyhawk bombers would support an advance by just The Royal Canadian Regiment. Advancing 100 metres every two minutes to keep pace with the artillery lifts, the RCR were to march 11 kilometres right into Agira.

First Brigade’s Brigadier Howard Graham thought the plan “nonsense.” Although most of the ground was level, it was thick with vineyards and orchards. The RCR were sure to fall behind. No time was given for reconnaissance, the RCR were to just get going. Reaching the start line required marching three kilometres in searing afternoon heat.

AGITATORS

Lieutenant-Colonel R.A. Lindsay of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry chats with Lieutenant Colin McDougal on July 28, 1943.

While Simonds, his staff and many British officers, dignitaries and correspondents gathered on Monte Assoro for the show, the RCR slogged through the heat on either side of the main road along which Three Rivers Regiment tanks rolled in column. With the barrage pounding the ground ahead and a massive smokescreen cloaking the advancing force, all seemed to go smoothly at first.

Then out of the dust ahead, German mortars began pounding the reserve companies further back from the barrage. The lead RCR companies, moving in arrowhead formation, fell farther behind the barrage with men pushing through grapevines or winding around fruit trees. Irrigation ditches had to be jumped or climbed through. Deadly accurate fire from the overlooking heights struck soldiers and tanks alike.

‘A’ Squadron moving with the RCR lost 10 Shermans with four tankers killed and 13 wounded. As the RCR advance ran out of steam, Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph Crowe lost wireless links to his companies. Rushing forward with five signallers and two pioneers, Crowe mistook a German machine-gun position for some of his men and the party was pinned down. Grabbing a rifle, Crowe charged the gun alone and was cut down. With Crowe dead and the wireless sets lost, the attack crumbled.

British Eighth Army soldiers scramble through rubble in Catania

RUBBLE ROUSERS

Allied carriers take supplies into the captured town of Centuripe.

A renewed barrage on July 26 kicked off a new advance by 2nd Brigade’s battalions to capture heights codenamed Lion, Tiger and Grizzly. The three spots held the keys to Agira.

The PPCLI went in behind a barrage of 2,000 shells and managed to keep the pace between lifts. Although stalled briefly by machine-gun fire from a highway maintenance building dubbed the “Schoolhouse” for its red brick colouring that mirrored the colour of many Prairie schools, ‘D’ company managed to fight past the position and was soon atop Lion.

Correspondent Ross Munro interviewed several German prisoners shortly after this action who told him they had nicknamed the Canadians the “Red Patch Devils.” No matter how much machine-gun and mortar fire they threw at the Canadians, they said, the devils with the red patch on their shoulders just kept coming. The division would wear the nickname with pride forever more.

The Loyal Edmonton Regiment, meanwhile, enters Modica on July 13, 1943.

Tiger fell to the Seaforths the next day. Grizzly proved to be two closely grouped summits and it took both the Seaforths and the Eddies to take them. They then staved off repeated counterattacks. Early on the morning of July 28, Vokes signalled Simonds that the door to Agira was open.

While the Germans pulled back to a new line anchored on Regalbuto, the Canadians entered Agira. Meanwhile, 3rd Brigade fought several hard actions in the Dittaino valley for high points before capturing the railway junction town of Catenanuova and turning north toward Regalbuto on July 30. Their job was not to reach the town, but instead to seize several hills overlooking a road that the British 78th Infantry Division would use to advance on Adrano.

When these hills fell on Aug. 2, the brigade moved from this front to a reserve position near Agira.

After the street battle for Leonforte, the July28 advance on Agira was cautious. Vokes had teed up artillery and planned to bombard the town at 3:45p.m. before pushing in the PPCLI. Captain G.E. Baxter of 1st Field Regiment (Royal Canadian Horse Artillery) was the forward observation officer who would direct the barrage. From an observation position, he saw no activity in Agira and so pressed closer and closer.

Deciding the Germans had decamped, he scrubbed the barrage. A fighting patrol into the town pulled back when fired on. But the Germans appeared few in number, so a two-company advance pushed forward and was greeted by a large crowd of civilians.

With Agira in hand, most of 1st Division took a two-day break beginning on July 29. On the evening of July 30, the Seaforths made history when their pipe and drum band played “The Retreat” in Agira’s main square surrounded by townspeople. CBC’s Peter Stursberg recorded the performance. Broadcast on many Allied networks, this was the first recording to come out of Axis-held Europe.

While the Canadians rested briefly, British 231st Brigade under Simonds’s command drove toward Regalbuto and, after heavy fighting, were on its outskirts by July 31. They were also spent. Simonds rushed 1st Brigade forward and the town fell on Aug. 3.

STREET CLEANERS

Patricias patrol Agira

Although the road was open to Adrano, it was reserved for the British 78th Infantry Division coming up on the Canadian right flank. Simonds shifted his division two kilometres north to advance through the rugged Salso River valley. Strewn with boulders, the route was impassable to tanks. Infantry alone would go forward with mules carrying their heavier equipment, weapons and ammunition.

The march proved the campaign’s worst. Through a stark wilderness with Germans holding various steep hills on the north flank, each having to be taken in turn, the battalions struggled onward. Aug. 6 brought them to heights outside Adrano. Here, 3rd Brigade passed through and the Van Doos led the way up to the town’s outskirts and sent in a patrol before pulling back to let the British take the town.

VICTORY TOAST

An Eighth Army soldier receives a warm welcome from local Sicilians at the port of Catania on Sicily’s east coast.

WOUNDS OF WAR

Medics from the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada treat a Sicilian girl with infected insect bites.

The role of the Canadian Division and Three Rivers Regiment tanks in Operation Husky was done. The two other regiments of 1st Canadian Armoured Brigade that had not served alongside 1st Infantry Division, played a small role supporting British units to the east in the campaign’s final days. It was here the last Canadian died in Sicily.

When German bombers struck the Ontario Regiment (Tank) depot on Aug. 12, bombs set off explosions of munitions and fuel. Trooper Richard Arthur Burry, 26, perished. The last Canadian casualties came on Sept. 2 when 12 nursing sisters from No. 5 Canadian General Hospital in Catania were wounded by an anti-aircraft shell strike. Canadian casualties overall, including those lost at sea prior to the invasion, numbered 2,310 of whom 562 died.

Gunners of the 7th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, The Royal Canadian Artillery, disembark at Catania on Dec. 8.

The 1st Division had marched about 200kilometres—farther than any Eighth Army division.

Originally their role was to have been minor, but Montgomery had been forced to call upon them to “bear the brunt of the fighting…. No other division in the Allied force,” concluded one Canadian army report “made a larger contribution to victory.” Operation Husky knocked Italy out of the war. Mussolini had been deposed and arrested on July 25 and the Italian government announced its surrender to the Allies on Sept. 8.

Patton’s tangent to Palermo meant the Germans had the opportunity to escape, largely by ferry. Unhindered in the evacuation by either Allied naval or air power, almost 40,000 crossed the strait to form the nucleus for a rapid buildup on the mainland with Kesselring determined to fight the Allies for every inch of Italy.

MARCHIN’ ON

Foot- and vehicle-borne Canadian infantry march through an Italian village in pursuit of Germans in September 1943.

The Germans used their escape to claim Sicily more a victory than defeat. This was untrue. The Germans had suffered a drubbing, with 6,663 lost as prisoners and about 5,000 killed. On July 26, Allied high command decided to proceed with invading the mainland.

There was no thought of the Canadians being returned to Britain to rejoin First Canadian Army. Instead, they would be one of two Eighth Army divisions landing at Reggio Calabria as part of Operation Baytown on Sept. 3. Thereafter, joined in early 1944 by I Corps and the 5th (Armoured) Division, the Canadians carried out the long campaign up the Italian boot.

Seaforth Padre Roy Durnford looked back in his diary to Operation Husky’s conclusion. The Canadians, he wrote, “proved to be men of sterling worth in the face of great odds. I…see [too, the] many dead faces—unforgettably imprinted on my mind. They were the faces of brave men who were ready to pour out their lives to the last full measure of devotion.”

The Agira Canadian War Cemetery offers a commanding view of the surrounding countryside.

SOLDIER TO SOLDIER

Private Joe Pakokis of The Loyal Edmonton Regiment stands alongside the grave of an Italian soldier near Pachino on July 11.