Like tossed rocks making ripples across a pond, the treaties and agreements that end wars can create shockwaves that reverberate over decades, even centuries. Personal. Societal. Political.

More often than not, the spoils of one side’s victory leave another side—and not necessarily the losers—drenched in blood and suffering somewhere down the line. So, it was after the two world wars of the 20th century.

The punitive measures imposed on Germany after 1914-1918 fuelled Naziism and another world war. Western diplomats redrew maps and carved up territories in the backrooms of Westminster and Washington and into the halls of Versailles. As a result, ethnic tensions were reignited in parts of Europe and the Middle East as long-established lines of demarcation were erased and realigned by political opportunists employing arbitrary, self-serving and short-sighted cartography.

Former enemies became friends and were rehabilitated after 1945, ultimately creating the economic powers of present-day Japan and Germany. But Europe was divided by an Iron Curtain dropped by the Soviet Union’s Communist masters. And communism didn’t stop there. Its reach was long, its grip firm.

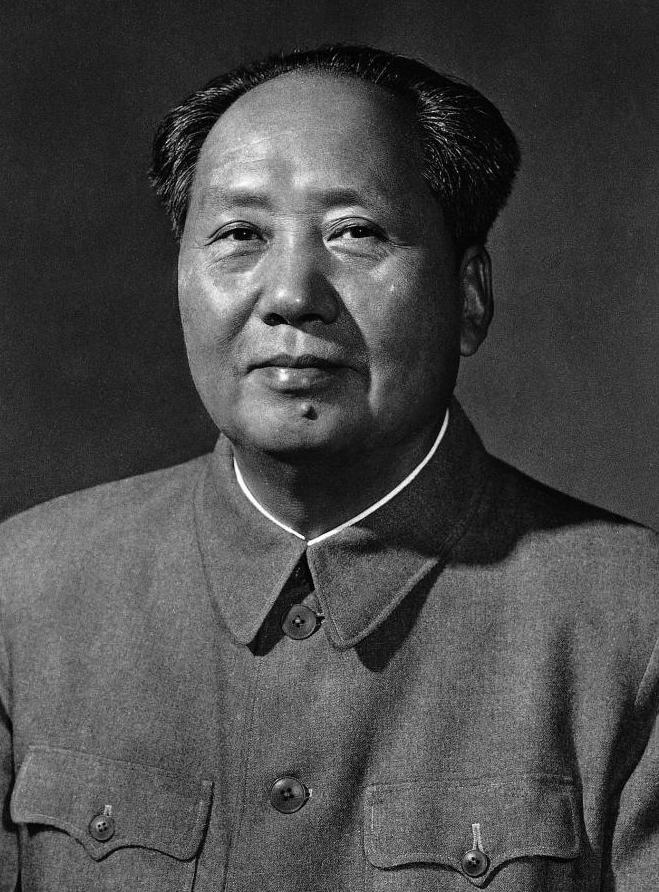

On Oct. 1, 1949, Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong declared the creation of the People’s Republic of China, ending a civil war between the Chinese communists and nationalists that began simmering in the 1920s and had raged since the end of the Second World War.

declared the creation of the People’s Republic of China, ending a civil war between the Chinese communists and nationalists that began simmering in the 1920s and had raged since the end of the Second World War.

Communism eventually took hold in parts of Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia. The Cold War, and an accompanying nuclear-arms race, cast ominous shadows around the globe for four decades. Proxy wars pitted Soviet- or Chinese-trained and -equipped troops against those of the United States and its allies.

But the first direct confrontation between the so-called superpowers, who had been staunch, if not strained, Second World War allies, took place on the Korean Peninsula, which Soviet forces had entered on Aug. 9, 1945, followed a few weeks later by U.S. troops at Incheon.

Thirty-five years of brutal Japanese occupation had ended, only to be replaced by mounting tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union, both on and off the peninsula. Both sides and both Korean administrations wanted to reunite the Koreas. How to do it, and who would rule, was another matter. Both Seoul and Pyongyang considered themselves the legitimate administrator of a unified state.

On June 25, 1950—more than 11 years before the wall went up in Berlin—North Korean People’s Army troops, trained and equipped by the Soviets, crossed the 38th parallel into the south. Seoul, known as Hanyang for the seven centuries it had been the capital, fell in less than a week.

Writing for the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in 1993, Florida State University historian Kathryn Weathersby described the invasion as “one of the defining moments of the Cold War.”

U.S. President Harry S. Truman signs the declaration of a national emergency on Dec. 16, 1950

“The North Korean attack so alarmed Washington that President (Harry) Truman abruptly reversed the meticulously considered policy…that had placed Korea outside the American defense perimeter, and instead committed U.S. armed forces to the defense of South Korea,” wrote Weathersby.

The Truman administration concluded that the conflict with the Soviet Union had entered a new and more dangerous stage.”

“Viewing the North Korean assault as a case of Soviet aggression, likely a probing action to test Western resolve, the Truman administration concluded that the conflict with the Soviet Union had entered a new and more dangerous stage.” The United Nations immediately drafted Security Council Resolution 82, calling for an end to hostilities and the invaders’ withdrawal. The Americans mobilized their forces.

Fearing execution, captured Chinese soldiers under South Korean guard beg for their lives in 1951.

“The attack upon Korea makes it plain beyond all doubt that communism has passed beyond the use of subversion to conquer independent nations and will now use armed invasion and war,” declared Truman. Further advances by communist forces, he said, “would be a direct threat to the security of the Pacific area and to United States forces performing their lawful and necessary functions in that area.” A line had been drawn—and North Korean soldiers were already 56 kilometres across it.

U.S. Marines inspect captured enemy equipment at Incheon on Sept. 7, 1950.

Lou Bailey at his home in Iroquois, Ont. Korean War veterans, like many of their contemporaries, were virtual shut-ins throughout the COVID pandemic.

Lou Bailey was one of six young men from the

St. Lawrence Seaway community of Iroquois, Ont., who signed up and went halfway around the world to stem the Red tide of communism. Only five came back. But for a pack of smokes, Bailey might have made it four.

As a member of 56 Transport Company, Royal Canadian Army Service Corps, Bailey drove trucks, delivering food and supplies over rough, sniper-infested mountain roads to Canadian and other UN units on the front lines near the 38th parallel.

They were likely driving  trucks—automatic transmission versions of the two-and-a-half-ton GMC vehicles that saw the Allies through the Second World War, the iconic Jimmy or deuce-and-a-half. They called the M211s “the Cadillac of Deuces.”

trucks—automatic transmission versions of the two-and-a-half-ton GMC vehicles that saw the Allies through the Second World War, the iconic Jimmy or deuce-and-a-half. They called the M211s “the Cadillac of Deuces.”

“They weren’t worth a goddamn on the hill,” said Bailey. “You’d be trying to climb up the hill and it was in the lowest gear, you’d be doing about three-four miles an hour.”

The next thing he knew, he felt the barrel of a rifle against the back of his head.”

He would do grocery runs into Seoul and by the time he got back to the camp, “there were no groceries.” People would hop on the back of the truck and unload it in the dark, on the run.

“So, we fixed that,” he said. “We put one guard in the back end with a bayonet and a rifle. That solved that problem.”

One day, Bailey pulled over for a break. He wandered off the side of the road and sat on a rock. The next thing he knew, he felt the barrel of a rifle against the back of his head.

Bailey turned around to see a very young North Korean soldier staring at him, his rifle raised. “I just told myself, ‘relax,’” said Bailey. “I had no helmet on, my rifle was in the truck. But I wasn’t scared of anything.”

He casually reached into his breast pocket for a pack of American cigarettes. Bailey “drank like a fish” in those days, but he didn’t smoke. In Korea, however, he always carried a pack simply because they came with the rations and “they were free.”

“I took it out of my pocket and threw it at him,” said Bailey. “He grabbed it, looked at me, nodded his head and walked away. I remember it quite vividly.”

Sergeant Tommy Claxton, a paratrooper with 25 jumps under his belt, was the first of the six Iroquois soldiers to die and the only one to do so overseas. He drowned in a boating accident while on leave. Lou Bailey died 15 months after this interview, on Nov. 5, 2021. He was 93.

After almost five years of postwar tensions between the liberating forces of the Second World War, Soviet-supplied troops of North Korea invaded South Korea on June 25, 1950, bringing the emerging Cold War to an early boil. The (North) Korean People’s Army entered Seoul three days later. The United Nations condemned the offensive and called on member countries to provide military assistance to the South. No war was ever declared.

The first United Nations forces to cross the 38th parallel dividing the Koreas hold a sign-posting ceremony declaring the fact.

U.S. President Harry S. Truman called it “a police action.” Early fighting was disastrously ineffectual, but American troops eventually broke out at Pusan and UN forces drove the invaders back across the 38th parallel and deep into North Korea. China would dispatch an army and the tide of war would shift again. Canadians joined the fighting in February 1951. Eventually, the two sides settled in on either side of the 38th parallel.

U.S. Marines fight in the streets during the September 1950 liberation of Seoul.

Over the next three years, the combatants would suffer more than a million combined casualties. The fighting would end in an armistice in July 1953. No formal peace treaty was ever signed.

It had been just five years since the bloodiest and most costly war in human history—some 50 million dead, the second time a world war had claimed tens of millions of lives in just over two decades.

Our objective is not to make war. We are…doing our best to prevent war”

Private Kenneth O’Brien (above) of the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, is carried off on a stretcher to the Commonwealth field ambulance on Feb. 23, 1951. He died en route, one of the first Canadian casualties of the war.

Nobody wanted a third world war. Nobody wanted war at all. “Our objective is not to make war,” Prime Minister Louis St-Laurent assured Canadians in an Aug. 7, 1950, radio address. “We are…doing our best to prevent war.”

Nevertheless, 26,791 Canadians would fight in Korea over the next three years, reaching a peak strength of 8,123. It constituted the third-largest complement among the UN force’s peak of 932,539 personnel from 16 countries. Five hundred and sixteen Canadians would die in Korea, 312 of them in combat; 1,235 were wounded or declared missing in action, and 33 were captured and later released.

War was a tough sell. During a June 29 news conference, a reporter told Truman “everybody is asking in this country: ‘are we or are we not at war?’” “We are not at war,” insisted the plain-speaking president. Korea, he said, “was unlawfully attacked by a bunch of bandits…. And the members of the United Nations are going to the relief of the Korean Republic to suppress a bandit raid on the Republic of Korea.”

The armistice, while it stopped hostilities, was not a permanent peace treaty between nations.”

“Mr. President, would it be correct…to call this a police action under the United Nations?” he was asked. “Yes,” replied Truman. “That is exactly what it amounts to.” Not a war. A police action. A war by any other name, the designation meant there was never any official declaration of war. And, while the fighting officially ended with the signing of an armistice on July 27, 1953, no peace treaty was ever reached.

The Korean War, in other words, never technically existed. Nor has it ended. “The Korean Armistice Agreement is somewhat exceptional in that it is purely a military document—no nation is a signatory to the agreement,” says a U.S. briefing document. “The armistice, while it stopped hostilities, was not a permanent peace treaty between nations.”

26,791

Number of Canadians that served in the Korean War

Korea, meanwhile, became known as The Forgotten War. Its veterans struggled for recognition. Sixty years later, 82-year-old Korean War veteran Donald Dalke of Lethbridge, Alta., recalled how he was told at the outset not to expect a medal for his service with the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery on the other side of the Pacific Ocean.

“We were informed we couldn’t qualify for medals because, as far as the government was concerned, they did not declare war and so there’s no war,” Dalke told Maclean’s magazine in 2013. “They said ‘We’ve just offered some men to the United Nations, therefore, it’s looked at as a police action.’”

Career soldiers complained and eventually received medals. But volunteers weren’t recognized for another 30 years. “The Gulf War came up and they got every medal that was in the box,” said Dalke. “That was the point we really raised hell and they said ‘Well, I guess you can have that [volunteer] medal.’”

American propaganda focused on communist aggression.

St-Laurent considered the invasion a critical test of the ability of the five-year-old experiment known as the United Nations to “resist communist aggression” and whether the 60-member body could consolidate a contested position and act on it. It managed to do so, thanks largely to what the Constitutional Rights Foundation described as “a fluke of history.”

At the time, the Soviets—one of five permanent members the Security Council members with veto power—were boycotting UN meetings over the fact that China’s permanent council seat was occupied by a representative of the anti-communist government on Taiwan. Neither the Soviets, nor China’s Communist regime, could therefore cancel UN-sanctioned action against the invasion by veto.

Security Council Resolution 83 passed by seven votes to one (Yugoslavia). Two members didn’t vote (Egypt and India), and the USSR was absent. The resolution authorized the UN to “furnish such assistance to the Republic of Korea as may be necessary to repel the armed attack and to restore international peace and security in the area.”

American UN delegate Warren Austin wields a Russian-made submachine gun captured by U.S. troops in July 1950. He accuses the Soviets of delivering arms to North Korea.

On June 29, Foreign Affairs Minister Lester B. Pearson told Parliament: “Canada will do as she has always done—her full duty.” In July, Canada’s navy dispatched three destroyers to the UN force in Korean waters. No. 426 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force, sent “urgently needed” long-range transport aircraft.

The only way to prevent a world war is to call a halt to aggression. That is what is being done now.”

Even as he professed to be doing his best to avoid war, St-Laurent upped the ante, announcing in August that Ottawa was creating a brigade, the Canadian Army Special Force, to “carry out Canada’s obligations…for service in Korea.”

“The only way to avoid war is by positive action to prevent it,” he said of the UN involvement. “The only way to prevent a world war is to call a halt to aggression. That is what is being done now.”

The U.S. dropped more bombs on North Korea than it had dropped in the entire Pacific theater during World War II.”

The resulting “police action” has since been described as one of the most destructive conflicts of the modern era, claiming about three million lives. At an estimated 2.7 million non-combatants killed, the Koreas reportedly racked up a higher civilian death ratio than any major conflict of the 20th century.

“The U.S. dropped more bombs on North Korea than it had dropped in the entire Pacific theater during World War II,” Max Fisher wrote for Vox in 2015. “This carpet bombing, which included 32,000 tons of napalm, often deliberately targeted civilian as well as military targets, devastating the country far beyond what was necessary to fight the war. Whole cities were destroyed, with many thousands of innocent civilians killed and many more left homeless and hungry.”

In 1984, U.S. air force General Curtis LeMay, the war’s head of Strategic Air Command, told official historians that “over a period of three years or so, we killed off—what—20 per cent of the population.” Michael Edson Robinson, a Korean history specialist at Indiana University Bloomington, says the conflict, known in South Korea as the 625 War for its June 25 start and in the North as the Fatherland Liberation War, scarred Koreans for generations.

2.7 Million

Civilians killed in the conflict

Her brother on her back, a war-weary Korean girl trudges past a stalled M26 tank at Haengju on June 9, 1951.

“It tore the peninsula in two, dividing it with the heavily fortified DMZ, a two-to-three-mile swath traversing the peninsula for 120 miles from southwest to northeast,” Robinson wrote in his 2007 book Korea’s Twentieth-Century Odyssey. “The more serious scars, however, were psychological. Koreans have lived the last fifty years in a state of war. Because of this, the peninsula is one of the most militarized areas in the world today.”

Both sides committed atrocities, including thousands of massacres. The South Korean government killed suspected communists en masse. The North tortured and starved prisoners of war. The conflict ripped families apart, propelling several million refugees south. Through the decades, the continuing tensions only deepened the divide between the two Koreas and the vastly different administrations and ways of life they forged.

South Koreans identify the bodies of some 300 political prisoners killed by North Korean troops

And so it continues. North Korean threats and military exercises, missile tests by both sides, and the presence of some 26,000-plus American troops on 73 bases across South Korea, all punctuated by periodic outbreaks of violence, are constant reminders that the dormant state of war on the Korean Peninsula could turn active at any time.

Lance-Corporal Doug Murphy

Lance-Corporal Doug Murphy was a young electronics technician in 191 Canadian Infantry Workshop, the Corps of Royal Canadian Electrical and Mechanical Engineers.

He and a handful of comrades were seconded for much of their time in Korea to a special British/Commonwealth unit he said “nobody’s ever heard of”—the Divisional Telecommunications, or Divtels, Workshop.

They were what he calls “a hobo bunch”—33 self-described oddballs, including a handful of Kiwi shipwreck survivors, all sleeping in an “old, ragged” squad tent made for 28. They serviced a whole division, doing installations and fixing anything electronic, from projectors to radios, and even medical equipment.

We didn’t go out and win battles. But we did a lot of unique work.”

“It wasn’t a dangerous story,” said Murphy. “We didn’t go out and win battles or anything. But we did a lot of unique work.” Much of that labour was focused on keeping aging Second World War-era technology, or older, functioning in rugged conditions. Instead of rifles, the Divtels wielded screwdrivers, pliers and specialized tools.

The oddballs became experts at tracking down obscure, forgotten and long-lost parts. What they couldn’t find in the brigade stores, they would beg, borrow or steal elsewhere. Much to the chagrin of their British hosts, military protocol wasn’t exactly a Divtels priority. Ranks and dress codes were an afterthought.

“We were so ‘unique’ that we were supposed to be attached for meals and so forth to the British signal corps regiment,” recalled Murphy, now 92. “But they were so strict with their ‘left-right, left-right’ and whatever the hell that they didn’t want to talk to us. So, we sorta ate in their place and they left us alone.”

The Divtels set up a darkroom with equipment from all over, fashioning processing drums from shell casings and scrounging chemicals, photographic paper and enlargers from a friend of a friend in the dental corps.

The first 124 men of 191 Canadian Infantry Workshop landed at Pusan, Korea, with the 25th Canadian Infantry Brigade on May 4, 1951. The brigade brought along 1,500 vehicles and more than 2,000 tonnes of stores.

The unit was allocated a muddy compound on the outskirts of Pusan, where it spent two weeks sorting a mountain of boxes, crates and stores, including some 109 tonnes of spare parts.

Four days and 500 kilometres later, it arrived in the brigade area just south of Seoul. The next day, it was ready to work as Canadian infantry saw action for the first time.

Besides electronics, the unit had specialists in other fields, including vehicle recovery and repair. The recoveries were often made under fire. Sergeant Trevor (Trapper) Allen earned a Military Medal pulling out a mud-bound dozer tank under an artillery barrage.

By the time the fighting ended, 191 Workshop had performed 22,000 field repairs on trucks, combat vehicles, artillery pieces, small arms, instruments and other equipment. Canadians in Divtels Workshop had fixed 7,600 radios. Murphy served 31 years, retired a captain, then stayed on as a civilian for another decade. He and wife Margaret, 94, live in Ottawa.

The Soviets had been arming and training North Korean troops for more than a year. Now, with a Communist government ensconced in Beijing, there began an influx of ethnic Korean troops into North Korea from China.

Two ethnic Korean divisions of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, followed by smaller units, first entered the North in the fall of 1949 after the Communist victory in China’s civil war, bringing with them weapons, equipment and battle-hardened experience. By mid-1950, they numbered between 50,000 and 70,000.

Combined with the Soviet-supplied training, tanks, artillery and aircraft, the North had a distinct military superiority over the South, which was equipped with U.S.-supplied small arms and little more. Its request for U.S. tanks had been denied.

With a 1949 population of more than 9.6 million, North Korea had amassed a wartime force of between 150,000 and 200,000 troops in 10 infantry divisions, a tank division and an air force division. It had 280 tanks, 200 artillery pieces, 210 fighter planes, 110 bombers and 35 reconnaissance aircraft.

South Korea, with an estimated 20 million citizens, was unprepared and ill-equipped for war.”

South Korean marines move toward the Han River from Kimpo airstrip in the area’s first UN offensive.

South Korea, with an estimated 20 million citizens, was unprepared and ill-equipped for war. On June 25, 1950, it had just 98,000 soldiers (65,000 combat, 33,000 support), no tanks and an air force of 12 liaison aircraft and 10 trainers. While the Americans maintained large military resources garrisoned in Japan, they had only 200-300 troops in Korea. Washington—and Ottawa, for that matter—were also not prepared for war, particularly one with ominous global implications.

Not unlike Russia and its Feb. 24, 2022, invasion of Ukraine, the North expected to defeat their adversaries in short order. Seoul, indeed, fell in days. The Korean People’s Army pressed on toward the port of Pusan, a strategic goal and the temporary seat of the South Korean government. But while the North conquered virtually all of Korea, this tiny enclave at the end of the peninsula, now known as Busan, would never be taken. With the war nearly won by the North, the U.S. offered assistance and the UN Security Council asked its members to step up.

Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes was a native Englishman, born in Stockton-on-Tees before his family moved to Canada and settled in London, Ont. He joined the Canadian Militia in 1926 and attended staff college in England. His ascent was rapid during the Second World War. Foulkes started as a major in 1939 and rose to lieutenant-general in 1944. As general officer commanding, he led the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division through D-Day and the Normandy campaign.

Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes, the defence chief, backed Canadian involvement on the Korean peninsula.

But Foulkes is probably best known for his role as general officer commanding I Canadian Corps in the Netherlands. On May 5, 1945, he summoned Wehrmacht General Johannes Blaskowitz to the Hotel de Wereld in Wageningen to discuss the surrender of German forces across the diked country they had occupied since May 1940.

Blaskowitz agreed to all of Foulkes’s proposals and, as Foulkes and Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands looked on, the German signed the surrender document the following day. Now, just five years later, Foulkes was chief of the general staff in Ottawa and advocating for Canada’s role in yet another war. He backed the idea of a Canadian infantry brigade for the 1st Commonwealth Division, yet he wanted to keep the Canadian army’s mobile strike force intact for the defence of North America.

Foulkes recommended a separate special force for Korea. Active force, Second World War veterans and adventure-seekers filled the ranks.”

He recommended a separate special force for Korea. Recruits were enlisted for 18-month stints. Active force, Second World War veterans and adventure-seekers filled the ranks. Normal recruitment standards were lowered since “the army would not wish to retain the ‘soldier of fortune type’ of personnel on a long term basis.”

A company of Patricias files across rice paddies as it advances on enemy positions in March 1951.

Units of the special force would be second battalions of the existing three permanent force regiments. The 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, was formed Aug. 15, 1950, as a component of the Canadian Army Special Force in response to the North Korean invasion. The new battalion trained in Calgary and at Canadian Forces Base Wainwright in Alberta before boarding the USNS Private Joe P. Martinez on Nov. 25, 1950. They arrived in Pusan in December and trained in the mountains for eight weeks before entering combat service in February 1951. They would form a component of the 27th British Commonwealth Brigade of IX Corps in the U.S. Eighth Army.

As such, 2PPCLI was the first Canadian infantry unit to fight in the Korean War. Special force second battalions of the Royal Canadian and Royal 22e regiments would arrive during the following months. By early spring 1951, more than 8,000 Canadian troops were fighting alongside 12,500 Brits, 5,000 Filipinos and 5,000 Turks.

Royal Canadian Air Force Flying Officer James Shipton

As a navigator with 426 (Transport) Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force, Flying Officer James Shipton did two tours on the Korean airlift hauling people, cargo and mail into Japan and wounded back to California.

Flying aboard Canadair North Stars out of McChord Air Force Base (AFB) in Tacoma, Wash., Shipton and his crewmates would travel 2,400 kilometres to Elmendorf AFB in Alaska, then another 2,400 kilometres to Shemya at the far end of the Aleutian Islands. The final leg covered 3,400 kilometres to Tokyo.

Crews would often lay over partway, then replace the next crew through. The Shemya-Matsushima run skirted the edge of Soviet airspace, keeping pilots and navigators on their toes. The difficult job was made worse by Soviet efforts to jam radio comms and navigational aids. Shipton sometimes plotted their progress by dead reckoning, but cloud cover often forced him to resort to pressure pattern navigation, which used wind velocities and horizontal gradients of atmospheric pressure to calculate course and position.

“It was a son of a gun,” said Shipton. “The leg down to Tokyo was a bit of a problem.” A remote island chain, the Pribilofs, extended toward Japan “and we never knew if the Russians had fighter aircraft there or not.” They didn’t. Once their payload was delivered, the Canadians would take reconfigured aircraft loaded with sick and wounded from Osaka, Japan, back to Fairfield-Suisun airport, later renamed Travis AFB, east of San Francisco, via Wake Island and Honolulu—55 stretchers stacked along the sides of the fuselage with seats down the middle.

Onboard nurses included Canadians on exchange to the U.S. air force. The round trip took at least 50 hours of flying and it was often complicated by icing, storms and hair-raising crosswind landings at the short, exposed airstrip on Shemya.

“The real challenge was for the pilots,” said Shipton. “The wind was so bad [at Shemya] they built the barracks in trenches. It was one hell of a spot.

“I remember sitting in that airplane looking out the right-side window and seeing nothing but runway.”

As is procedure for crosswind landings, the pilots would kick the rudder straight at the last second, touch the windward wheel down first, and bring it in. Two-thirds of 426 Squadron’s aircrew were seasoned Second World War vets. Shipton had joined in 1948.

3 Million

Kilograms of freight and mail transported to Korea by 426 Transport Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force

The four Merlin engine-powered North Stars and 12 aircrews made five flights a week. Shipton, a native of Kingston, Ont., navigated the journey 18 times. During the UN buildup between July 28 and Dec. 31, 1950, the squadron few 123 missions. In all of 1951, it logged 193; it flew 133 in 1952. By October 1950, aircraft were evacuating wounded soldiers from the war zone and, via the military air transport system of which 426 was a part, began airlifting patients to the U.S.

The final Canadian mission left McChord on May 31, 1954. No. 426 Squadron had flown 584 round trips, logged 34,000 flying hours, carried 13,000 personnel and airlifted 3,500 tonnes of freight. Shipton logged 1,685 hours during two deployments spanning much of the Korean War. He would go on to serve 37 years in the RCAF, retiring as a flight-lieutenant.

On Sept. 15, 1950, U.S. army troops and Marines, along with South Korean troops, launched an amphibious attack on Wolmido Island, at the mouth of the harbour at Incheon. They cut off North Korean supply lines and forced the opposition to retreat north of the 38th parallel.

With three Canadian destroyers—Sioux, Athabaskan and Cayuga—among the naval units supporting the operation, the attackers captured Kimpo airfield inside of three days. They controlled the entire Seoul area by Sept. 28.

Concurrently, the U.S. Eighth Army finally broke out of the Pusan Perimeter, where they had been confined for two months and nearly defeated.

UN forces invaded North Korea in October 1950 and moved rapidly toward the Yalu River bordering China. On Oct. 19, 1950, however, Chinese forces of the People’s Volunteer Army crossed the Yalu and entered the war. The UN retreated from North Korea. The Chinese were in South Korea by late December.

They cut off North Korean supply lines and forced the opposition to retreat north of the 38th parallel.”

U.S. marines take four North Korean prisoners following the American landing at Wolmido, near Incheon, in 1950.

In these and subsequent battles, Seoul was captured four times, and Communist forces were pushed back to positions around the 38th parallel before the front stabilized. For the war’s duration, the bulk of Canadian land-based operations centred on a small area north of Seoul between the 38th parallel on the south and the town of Chorwon on the north, and from the Samichon River east to Chail-li.

About 50 kilometres across, it was in the sector occupied by Commonwealth forces. Most Canadian combat missions took place inside the zone, fighting the Korean People’s Army and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army.

The Patricias (above) cross a log bridge in February 1951. Ted Zuber’s painting “Silent Night” (background) depicts the terrain near the 38th parallel dividing the Koreas.

There was little time to acclimatize. On Feb. 15, 1951, the 900 troops of 2 PPCLI, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel James (Big Jim) Stone, began a 240-kilometre journey to the front and Operation Killer, a counteroffensive aiming to push the Chinese and North Korean armies back to the other side of the Han River and recover the South Korean capital.

Ask a Korean War vet what they remember most about their time around the 38th parallel and, outside of the fighting, they’re likely to tell you something about the topography, the sweltering heat or the bitter cold.

It was cold from the outset, with the Patricias huddled northbound in the backs of uninsulated half-tracks for 48 hours on poor roads. Some were frostbitten and their weapons’ lubricants frozen before they even reached their destination on Feb 17.

“On the other side of every mountain [was] another mountain.”

UN troops fight in the streets of Seoul

They soon learned something about the Korean terrain, too, as they began their advance to Hill 404—like most peaks during the war, identified by elevation, in feet. They gained the high ground without a fight.

Near the village of Kudun, the mortar platoon came upon 68, mostly Black American soldiers and white officers, who had been shot and bayonetted by the Chinese. The bodies were stripped of clothing and weapons and left to freeze solid.

Lieutenant Colonel George Russell, a battalion commander with the 23rd Regiment of the U.S. 2nd Infantry Division, may have said it best in describing the Korean landscape: “On the other side of every mountain [was] another mountain.” On Feb. 21, the Patricias left the village of Sangsok and continued north to their next objective: Hill 419, defended by the Chinese.

They walked north through rain, snow and fog, threading through hills of 250-460 metres. ‘D’ Company was first to make enemy contact, a burst of fire from the high ground to the northeast near a village called Chohyon.

The following day, the battalion continued up the valley, clearing the heights on either side as they advanced. ‘C’ Company took the Pats’ first battle casualties when four were killed and one wounded during an attack on Hill 444.

A machine-gun crew from the Patricias ‘C’ Company fights off an attack at Hill 444

Hill 419 stood at the head of the valley, overlooking the pass into the next valley. Opposition increased as the battalion approached; the Patricias consolidated and prepared to attack the following morning.

At 9 a.m. on Feb. 23, ‘C’ and ‘D’ companies launched an attack against strong resistance. They were well within sight of the Chinese defenders, who fired from multiple directions with artillery, rockets and small arms.

“Never in Italy or Germany were we under fire as intense as that.It was incredible.”

Neither company reached its objective. With darkness settling in and six soldiers killed along with eight wounded, the two companies dug in, conducting aggressive patrols while the Australians fought nearby on Hill 614.

Supported by air and mortar bombardment, ‘D’ Company reached the forward edge of the objective on the 24th, coming under fire from in front and both flanks. It was forced to withdraw and dig in.

Privates John Joyal, Henry Hayward and Donald Beebe of the Patricias fire a mortar during training at Miryang in February 1951.

“United States air force jets and corsairs together with U.S. mortars and the battalion’s own support weapons under Captains Lloyd Hill of Kentville, N.S., and Andy Foulds of Vancouver pounded the objective,” wrote Canadian Press correspondent Bill Boss in a story placelined “On the Central Front, Korea.”

Sergeant Bert Holigan of St. Catharine’s, Ont., told Boss the company got to within 200 metres of the summit “by means of excellent fieldcraft combined with fire and movement.” The Chinese, however, were unfazed.

“Although we called down mortars, artillery and air rockets, the Chinese were still there when we attacked,” said the company commander, Major Bill Stutt of Calgary. “If we had been fighting Germans, we would have been advancing today.

“Never in Italy or Germany were we under fire as intense as that. It was incredible. It chopped off bush briar at the six-inch level. Only fieldcraft carried us through.”

Boss reported that Canadian mortars subsequently dusted 419 with phosphorus bombs, starting fires. “The whole hill spouted smoke. As the Chinese left their dugouts they drew Canadian fire.”

The Chinese withdrawal afforded the Canadians their first rest in a week. Boss reported that they spent Sunday the 25th on a ridge two kilometres south of their objective “after banging hard into the enemy’s main defences south of the 38th parallel.”

Grateful for the break, however brief, they were “heating rations, doing their washing and recounting exploits of the last few days in full view of the enemy across the way,” he wrote.

Patricias (background) clean their weapons during a lull in the fighting. UN troops question a Chinese PoW in November 1950. (above)

“The Canadians, especially the Second World War veterans, were confounded by the Chinese laissez-faire.”

The Canadians, especially the Second World War veterans, were confounded by the Chinese laissez-faire.

“Can you imagine talking like this in the German war in full view of the enemy?” Holigan said to Boss, who had also accompanied the Canadians throughout the Italian campaign of 1944.

“Within five yards of him he rains absolute hell on you; here he ignores you utterly. Know what those Chinese are doing now? They’re rubbernecking upwards, laughing—and will do so until they’re killed.”

The fate of the Patricias rested with the Aussies on Hill 614 to the east. The battalion continued patrolling until the Australians took 614 on Feb. 27.

“As a result of this success, Point 419 became untenable by the enemy, being dominated by Hill 614,” said the army history. 2 PPCLI took the objective on the 28th without serious opposition but, by the end of its first week of action, the battalion had suffered 10 killed and more than 21 wounded.

The fight was on.

Artillery sergeant, Alex Kowbel

Alex Kowbel was an artillery sergeant during the Second World War. He served in France, the Netherlands and Germany.

“I was 19 and stupid,” he says.

By the time the Korean War erupted five years after WW II ended, the five-foot-four, 110-pound native of Melville, Sask., was a seasoned veteran with two university degrees.

Instead of hefting 105mm rounds pounding the enemy’s front line, he became a logistics captain in the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps, ensuring Commonwealth troops made it to the front and, for the most part, back again.

“I was a sergeant and a young kid when I went to World War 2,” said Kowbel, now 100 years old. “When I went to Korea, I went as an officer and I had good deal more education. It certainly was different for me; I don’t think it was much different for an artillery sergeant—you’re shooting your gun; I got posted into a staff job.”

He worked alongside British officers under an Australian commander. Kowbel was the only Canadian in the group. Moving back and forth between Korea and Japan, he and his colleagues handled logistics for the Commonwealth contingent.

He got more experience at the staff work than he had bargained for, overseeing the movement of Commonwealth troops by land, sea and air.

“My major had gout, so he didn’t work too much,” he explained. “And the lieutenant-colonel, who was supposed to be the staff officer, was studying to be a priest over there. So, I got all three jobs.”

Logistics—the movement, supply and maintenance of personnel, materiel and equipment—represents the single-most important element of a military campaign.

“It is of vital importance for any military operation and, without it, operations could not be carried out and sustained,” says a NATO brief on the subject.

Kowbel’s command had two ferries at its disposal, each with a capacity of 400 troops, travelling twice a week from Japan to Korea and back again.

Kowbel co-ordinated the comings and goings of tens of thousands of troops, right down to solving the challenges facing individual soldiers. In one case, he stopped a ship off the Japanese coast and commandeered a launch so he could reunite a homeward-bound Australian soldier with his Korean bride on their trip to Australia.

After the war, Kowbel stayed on in the military, survived a plane crash and retired a major. He joined the public service, travelled the world and was instrumental in setting up Canada’s environmental protection service.

He has visited South Korea several times since he served there, and the veteran of two wars says the South Koreans have been the most grateful of liberated peoples.

“They call it ‘The Forgotten War,’” he said. “But the Koreans haven’t forgotten it. They don’t forget those of us who served in the Korean War. Every Christmas they give us presents and hold a little get-together.”

There are a handful of place names the mere mention of which can stir the souls of Canadians who have even a cursory knowledge of their country’s military history. The Plains of Abraham. Queenston Heights. Vimy Ridge. Juno Beach. Kapyong.

In The Forgotten War, it was here, in April 1951 on the peaks overlooking the picturesque Kapyong Valley leading to Seoul, that the 118th Division of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (PVA) launched the main element of its spring offensive.

The two forward battalions at the tip of the defensive spear comprised 1,500 men of the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (RAR), and 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry.

The Canadians and Australians bore the brunt of the assault, yet they stopped 10,000-20,000 Chinese soldiers in their tracks. Today, the battle is widely regarded as the most significant action fought by either allied army in Korea, and Canada’s most famous battle since the Second World War.

In three days of fighting, the two battalions played a primary role in blunting the Chinese offensive. Their stalwart defence at Kapyong was key in preventing a breakthrough against the UN central front, the encirclement of U.S. forces in Korea and the ultimate capture of Seoul.

The Canadians and Australians bore the brunt of the assault, yet they stopped 10,000-20,000 Chinese soldiers in their tracks.”

Patricias’ riflemen (background) move to the front lines near the 38th parallel. Patricias Private Vernon Burke (above) checks trenches for Chinese troops in April 1951.

Operation Killer, the UN counteroffensive that had begun in February, had pushed the PVA north of the Han River, the primary waterway linking the central-western region of the peninsula with the Yellow Sea.

In see-saw fighting, the allies had recaptured Seoul in mid-March and they were once again approaching the 38th parallel. But after tactical errors cost the UN forces a series of defeats, U.S. President Truman had fired his blustery commander and Second World War icon, General Douglas MacArthur.

MacArthur had been hailed a military genius after his successful amphibious assault at Incheon. On Truman’s orders, however, he had followed up with the full-scale invasion of North Korea, which brought China into the war and dealt the UN effort an embarrassing blow. Eventually, MacArthur was compelled to withdraw below the 38th parallel.

Private Morris J. Piche of the Patricias is helped to an aid station in the Kapyong Valley by Lance Corporal W.J. Chrysler (above).

Though the military situation had stabilized by the spring of 1951, MacArthur continued to publicly criticize his superiors and attempted to escalate the conflict.

In a March 21, 1951, letter to Republican congressman Joe Martin, the general declared that peace in Europe depended on the outcome of the war in Korea.

“It seems strangely difficult for some to realize that here in Asia is where the Communist conspirators have elected to make their play for global conquest,” he wrote, “and that we have joined the issue thus raised on the battlefield; that here we fight Europe’s war with arms while the diplomatic [sic] there still fight it with words; that if we lose the war to communism in Asia the fall of Europe is inevitable, win it and Europe most probably would avoid war and yet preserve freedom.

“As you point out, we must win. There is no substitute for victory.”

Sniper and artist Ted Zuber depicts April 1951 action in the Kapyong Valley (background). Chinese troops (above) capture American soldiers near Wonson in 1951.

“As you point out, we must win. There is no substitute for victory.”

Truman seemingly had no choice but to relieve the general of command, though the decision remains a subject of impassioned debate to this day.

Said the president: “I fired MacArthur because he wouldn’t respect the authority of the president. I didn’t fire him because he was a dumb son of a bitch, although he was.”

MacArthur’s replacement was General Matthew B. Ridgway, commanding general of the 82nd Airborne Division. During the Second World War, he had led the “All Americans” through fighting in Sicily, Italy and Normandy, on to the Battle of the Bulge and into Germany.

Nicknamed “Tin Tits” or “Old Iron Tits” for his habit of attaching hand grenades to his chest webbing, he would later persuade President Dwight D. Eisenhower to refrain from direct military intervention in Indochina. The decision has been credited with delaying the Vietnam War by more than a decade.

Yet Ridgway’s most recognized military accomplishment was to resurrect UN prospects during the Korean War. Among his first acts were to restore his soldiers’ confidence and clean house, replacing ineffectual leadership and reorganizing the command structure.

Korean ration-bearers cover their ears as they pause alongside a Royal New Zealand Artillery battery in mid-April 1951.

Facing UN-imposed limitations on his forces’ ability to bomb supply bases in China and bridges across the Yalu River bordering China and North Korea, Ridgway shifted his army from an aggressive stance to fighting protective, delaying actions, making copious use of artillery in the process.

Chinese casualties began to rise. The momentum of the war shifted, and Kapyong was a linchpin.

U.S. Army General Douglas MacArthur (background), Major General Courtney Whitney, Lieutenant General Matthew B. Ridgway and Major General William B. Kean visit the front lines near Suwon. A Patricias Bren gun team prepares to move out during a field exercise near Miryang (above).

South Korean troops were establishing positions at the northern end of the Kapyong Valley when two PVA divisions—the 118th and the 60th—launched the area offensive at 5 p.m. on April 22.

The Chinese easily infiltrated the gaps between the poorly organized defensive positions. Facing pressure all along the front, the South Korean defenders soon gave ground and broke, abandoning weapons, equipment and vehicles as they streamed southward out of the mountains.

Chinese casualties began to rise. The momentum of the war shifted, and Kapyong was a linchpin.”

Patricias and Katcoms (Koreans attached for training) appear relaxed during a break in front-line action.

By 11 p.m., the South Korean commander had lost all communication with his units. At 4 a.m., supporting New Zealand troops were withdrawn, sent back, then withdrawn again by dusk on the 23rd. The South Korean defences had collapsed. On their way out they let the Canadians know the Chinese were coming.

“It was then, about mid-afternoon, that the rumour of the collapsing front acquired a meaning,” Captain Owen R. Browne, the officer commanding ‘A’ Company, wrote in the regimental journal.

“From my arrival until then both the main Kap’yong Valley and the subsidiary valley cutting across the front had been empty of people. Then, suddenly, down the road through the subsidiary valley came hordes of men, running, walking, interspersed with military vehicles—totally disorganized mobs. They were elements of the 6th ROK [Republic of Korea] Division which were supposed to be ten miles forward engaging the Chinese. But they were not engaging the Chinese. They were fleeing!

“I was witnessing a rout,” continued Browne. “The valley was filled with men. Some left the road and fled over the forward edges of ‘A’ Company positions. Some killed themselves on the various booby traps we had laid, and that component of my defensive layout became worthless.

“We knew then that we were no longer 10-12 miles behind the line; we were the front line.”

With that disconcerting prospect fresh in their minds, and ROK troops still pouring past them, the Canadians started digging trenches and positioning themselves on Hill 677, establishing positions along the 1.5-kilometre ridge connected to it.

They were on the west side of the Kapyong River. On the other side of 677, atop Hill 504, were the Aussies, dug in and ready for a fight.

The 16th Field Regiment of the Royal New Zealand Artillery were in support, with troops of the British First Battalion, Middlesex Regiment at the rear along with the 72nd U.S. Heavy Tank Battalion—15 tanks—alongside the main road that split the valley.

“No retreat, no surrender,” Stone told his men.

The Chinese struck 504 first, engaging the Aussies of 3 RAR, infiltrating the brigade position, and then hitting the Canadian front.

“They’re quiet as mice with those rubber shoes of theirs and then there’s a whistle,” said Sergeant Roy Ulmer of Castor, Alta. “They get up with a shout about ten feet from our positions and come in.”

Waves of massed Chinese troops sustained the attack throughout the night of April 23. The Australians and Canadians were facing the whole of the Chinese 118th Division. Unrelenting battle continued through April 24.

“The Chinese employed all their familiar battle procedures in the attack—whistles, bugles, a banzai chorus, concerted action on the word of command and massed assaults followed one another in swift succession,” reported CP’s Boss.

“This was familiar only by description for these United Nations troops who until now had fought mainly an advancing war against token resistance. Now it was grim reality.”

1.15 million

Peak strength of Communist forces during the Korean War

Ted Zuber depicts an encounter with Chinese forces on the Korean peninsula (background). The nature of the war shifted with the entry of heavily supported Chinese troops (above).

The battle was unrelenting. It devolved on both fronts into hand-to-hand combat with bayonet charges.

“The first wave throws its grenades, fires its weapons and goes to the ground,” explained Ulmer, who had served as a company sergeant-major with the Loyal Edmonton Regiment during the Second World War.

“It is followed by a second which does the same, and a third comes up. Where they disappear to I don’t know. But they just keep coming.”

United Nations mountain warriors won their spurs today, holding their front and refusing to budge.”

Facing encirclement late on the 24th, the Australians were ordered to retreat to new defensive positions.

The Patricias were surrounded, too. “But they held,” wrote Boss.

Captain John Graham Wallace (Wally) Mills of Hartley, Man., a Second World War vet fighting his first action as a company commander, ordered his ‘D’ Company men into the slit trenches. Then he called down artillery and mortar fire on his own position several times during the early morning hours of April 25 to avoid being overrun.

A patched-up Sergeant Neil McKerracher of the Patricias (above) surveys the front after he was hit by shrapnel.

“Guns and mortars rained hell on that hill from 2 a.m. to 6 a.m.,” Boss wrote, his censored copy of the day void of identifying specifics such as battalion and company.

“Torrents of hot metal fragments decimated the Chinese ranks,” said an account related by the Loyal Edmonton Regiment Military Museum.

The Chinese kept hitting Ulmer’s position until 4 a.m. on the 25th. By then, the forward platoon had almost exhausted its ammunition.

“The sergeant hurled his bayonetted rifle like a spear at his enemy,” Boss reported. “While two gunners stood up and gave covering fire from the hip, the remainder withdrew—but only 50 yards. There the company continued the fight, dividing the remaining ammunition and holding out until the enemy pressure relented.

“I counted 17 dead Chinese within inches and feet of those troops today and approximately 50 graves of enemy buried in the heat of battle,” continued Boss. “There were uncounted enemy dead where an intended rear and flank attack was thwarted.

“Another company fought at close quarters against waves of Chinese troops. This company shot and grenade[d] the enemy until its ammunition ran out.”

As the sun rose, 2 PPCLI, cut off from the rest of the UN forces, still held Hill 677. The Chinese had withdrawn. Ten Canadian soldiers were dead and 23 wounded. Australian losses were 32 killed, 59 wounded and three captured. The New Zealanders lost two killed and five wounded. Chinese losses were pegged at between 1,000 and 5,000 killed and many more wounded.

That morning, U.S. transport planes dropped food, water and ammunition to the exhausted Patricias.

1:7

Ratio of Canadian to Chinese troops in the Battle of Kapyong

Private John Lewis (above, centre) of the 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment, reflects on an overwhelming attack by Chinese troops.

Bill Boss’s April 25 wire service account of the battle, placelined West Central Sector, Korea, began: “United Nations mountain warriors won their spurs today, holding their front and refusing to budge even though outflanked and encircled. It was a knock-down, drag-out battle with wave upon wave upon wave of Chinese Communists who did everything but drive them from their positions.”

Five Patricias received valour medals and 11 were mentioned in dispatches for their actions at Kapyong. Mills, who had called in the mortars and artillery on his own position, was awarded the Military Cross.

On May 25, 1951, 2 PPCLI was transferred to the 25th Canadian Infantry Brigade within the 1st Commonwealth Division. For the rest of the war, the infantry battalions of the PPCLI, the Royal 22e Régiment and the Royal Canadian Regiment, squadrons of Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians), regiments of the Royal Canadian Horse Artillery and units of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps would rotate in and out of the war.

“The Canadians, especially the Second World War veterans, were confounded by the Chinese laissez-faire.”

Nursing Sister Jessie Chenevert

Seventy years on, the business-like efficiency tempered by a gentle bedside manner is still evident in Jessie Chenevert’s voice.

At 101 years old, the memories of her time working in a field hospital near the front lines of the Korean War, 25 kilometres north of Seoul, are still vivid.

“It wasn’t what we would think of as a hospital,” she said. “It was a field hospital—and it sure was a field hospital. It was in tents and old buildings and anything that the CO could scrounge from anybody became part of it.”

They managed about 90 beds—including about 20 surgical, 30 medical and a small burn unit. The more serious cases went on to better-equipped and -staffed British or American facilities. Once stabilized, patients were flown to the U.S.—a wartime first.

Chenevert said the mobile army surgical hospital depicted in the hit television series M*A*S*H was much more elaborate than the Canadian version.

“In the winter it was cold, the tents especially,” said the Ottawa native. “The buildings were all heated with these little pot-bellied stoves, so there wasn’t a lot of heat. We had buckets of coal that we put into these little, tiny stoves.

“The stoves would be in the middle of the room with a pipe going up through the ceiling and we had to put buckets around them to heat the water so we could bathe the patients.”

The casualties were in flimsy folding field cots. Boxes, cartons and anything else that would suit were used for bedside tables. There were no chairs for the nurses to sit with their charges. They knelt.

1,200

Canadian wounded in the Korean War

About 60 nursing sisters of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps served in Korea. They confronted the full range of battle wounds, accidental injuries and disease. Later, they nursed newly released prisoners of war.

Chenevert worked in a hospital in Japan before she made the hop across the water to join a revolution in wartime medicine on the Korean peninsula. The movement and treatment of wounded soldiers took great strides during the Korean War. The advent of the helicopter significantly reduced battlefield deaths and the catastrophic consequences of festering infection and blood loss.

The fatality rate for seriously wounded soldiers of the Second World War was 4.5 per cent. In the Korean War, it was 2.5.

“That success is attributed to the combination of the [MASH unit], and the aeromedical evacuation system,” wrote Dwight John Zimmerman for the DefenseMediaNetwork. It fundamentally changed army medical-evacuation doctrine.

About 30 kilometres from the 38th parallel, Chenevert and her colleagues were at the front line of military medicine—not an easy place to be, she said, “but we were pretty tough.”

She would remain in the army medical corps for 25 years. A lieutenant-colonel, she retired as director of nursing at the National Medical Defence Centre in Ottawa.

“I liked the work” she said of her Korea days. “It felt like we were doing something important.”

Sergeant-Major Joseph Quinn

A veteran of the Second World War, airborne medic Joseph Quinn stayed on in the military and went to Korea with 37 Canadian Field Ambulance, serving as sergeant-major of an army field hospital at the front.

Working out of tents in snake-, scorpion- and rat-infested terrain along the Han River, the Halifax native—now 102 years old—was far from the only war veteran in his unit.

“Most of us were a little older…and we knew what was going on,” he said, adding there were few surprises among his seasoned unit. “You just had to be careful because if you were in the open, they’d shoot you.”

Chinese blasted nightly propaganda over loudspeakers, urging the UN troops to pack up and go home. It wasn’t very convincing material. Then there was the time a Chinese lieutenant and his corporal were out laying communications cables and inadvertently wandered onto the Canadian position. They ended up prisoners in Quinn’s tent.

“They weren’t stupid,” despite the predicament they’d gotten themselves into, said Quinn. “They could understand English. They were in pretty good physical shape. I suppose they were around 30.”

The Korean War was known for its relentless artillery strikes. Quinn’s unit saw many burns and shrapnel cases.

Quinn had arrived aboard a landing barge at Incheon on April 4, 1952, told by the commanding general to always remember, “it’s 10-to-1 in front of you.”

Quinn and 34 men were posted to a casualty collecting station behind The Royal Canadian Regiment and the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry at Hill 355. They had one doctor.

“Most times I was the doctor, really, because he was always gone,” said Quinn.

The patrols went out about 9 p.m. The medics would await their return.

“You’d get a few in with bruises and blood, and then a lot of times you get one with a real bad wound, a sucking chest wound or shrapnel.”

Quinn triaged the incoming and the team would administer blood and plasma transfusions, perhaps giving morphine shots and even stitching them up, stabilizing the more serious cases as best they could before dispatching them to a better-equipped mobile unit, usually by helicopter the following morning.

“I think the worst I saw was a man with a sucking chest wound—with his chest wide open. I was scared he was going to lose his eye. So, I baseball-stitched it up, put him on his injured side so that the blood wouldn’t go to the other one, and I put some dope in his eyes and I shut them.”

Sometime in the night, an ambulance evacuated the man. “I got word back that he had lived. I was quite proud of that.”

Quinn was wounded by a phosphorous grenade and ended up in a military hospital in Kure, Japan. They kept him on as a ward master. He returned home a few months later and served 26 years in the military, retiring a warrant officer.

On July 30, 1950, three Canadian destroyers—Sioux, Cayuga and Athabaskan—arrived in Sasebo, Japan, under orders to join United Nations forces fighting in Korea.

Five other Tribal-class destroyers—Crusader, Huron, Iroquois, Nootka and Haida—would serve with the Canadian Destroyer Division, Far East, as part of the UN naval force off Korea during the war.

They blockaded the enemy coast, protected aircraft carriers from attack, bombarded railway trains and enemy-held coastal areas, evacuated troops and civilians, and delivered relief assistance to isolated South Korean fishing villages.

The Royal Canadian Navy’s official history of the conflict describes close support and interdiction as “incidental” to their main task—blockading. This, after Truman declared a blockade of the entire North Korean coastline on June 30.

It did not take long to dispose of the small, ineffective ‘gunboat navy’ which was all the North Koreans possessed.”

“It did not take long to dispose of the small, ineffective ‘gunboat navy’ which was all the North Koreans possessed, and of the obsolete propeller craft that made up their air force,” said the RCN’s official history of the conflict. “Virtually all danger of enemy attack upon the UN ships was thereby eliminated.”

Mines and shore batteries remained the main military challenges the navy faced, but they weren’t the only threats.

HMCS Nootka’s four-inch guns await action.(background) Canadian destroyers Athabaskan, Cayuga and Sioux (above) sit moored in Hong Kong in November 1950.

“There were also the problems created by geography, hydrography and climate,” said the history. “The western coast-line, for instance, is ragged and heavily indented, and the water is extremely shallow and dotted with islands, low-water mud flats, rocks and shoals.

“High, strong tides, of over thirty feet in some places, scour the muddy bottom, and channels are formed, obliterated and reformed with remarkable frequency. There are few harbours worth the name, and those that exist must be continually dredged to prevent silting.”

Under arrangements made just days prior to the Canadians’ arrival, naval responsibilities had been meted out according to capability: British and Commonwealth vessels would patrol the peninsula’s west coast; the larger and better-equipped U.S. navy would be responsible for the longer east coast. Each had its own set of challenges. The multitude of islands off the west coast, for instance, provided ideal conditions for what naval historians described as “the clandestine use of small craft.”

Sioux fires on North Korea during its last war patrol on Feb. 19, 1952 (above).

Had the enemy possessed large numbers of magnetic, acoustic and pressure mines, the west coast would indeed have been a dangerous place.”

“It required the utmost vigilance by surface ships and supporting carrier planes to prevent the infiltration of enemy agents, the movement of supplies and men, and even the fairly large scale transport of invading troops,” wrote official historians Thor Thorgrimsson and E.C. Russell.

Shoals made it difficult for even small ships to get close enough to shore to provide effective fire support for UN and guerilla forces and to attack enemy communication lines. Furthermore, conditions on the west coast made it easy for the enemy to lay mines; the area’s unique tides and currents made the floating mine a perennial problem.

“Had the enemy possessed large numbers of magnetic, acoustic and pressure mines, the west coast would indeed have been a dangerous place for the blockade forces, especially in the early months of the war when minesweepers were virtually unobtainable.”

Cayuga was assigned to the west coast support group, while Sioux and Athabaskan went to TE 96.50, the fast-escort element convoying ships between Japan and Pusan. For the war’s duration, only occasionally did the three Canadian destroyers serve together on the same operation under Canadian command.

A sailor aboard HMCS Cayuga watches an enemy shore installation explode after a UN bombardment (background).Cayuga’s commander, Captain Jeffrey V. Brock, briefs Koreans after the Incheon landings in September 1950 (above).

The harbour at Sasebo was a hub of activity. All present were acutely aware that U.S. forces were in the process of joining South Korean troops in staging a desperate defence at the key port of Pusan on the peninsula’s southeastern corner—a last stand against North Korean forces who now occupied Seoul and much of the rest of the country.

They knew in Sasebo that the success or failure of the land-based effort just a few hundred kilometres away—around Hirado Island and up and across the Korea Strait—was dependent on the navy’s ability to get troops and supplies into the battle area quickly and efficiently.

There was no time to spare. Athabaskan wasn’t in port 24 hours before it set out on its first operational mission, escorting the fast troop ship General Morton to Pusan. Athabaskan would conduct four such missions before the ship was transferred to the west coast group on Aug. 11.

Sioux remained at Sasebo for rescue duties, conducting only one seven-hour patrol of the approaches to Sasebo during the time it was attached to the escort element. On the 12th, Sioux was sent to join Athabaskan on the west coast.

While Cayuga’s commanding officer, Captain Jeffrey V. Brock—also commander of Canadian Destroyers Pacific—was busy making arrangements for supply and support with the British and the U.S., his ship was escorting the Royal Fleet Auxiliary vessel Brown Ranger, on a refuelling mission.

The day after returning to Sasebo, Cayuga transferred to the fast escort element. Between Aug. 9 and 24, it would sail five routine convoy missions to Pusan before joining the west coast blockade, where it would become the first RCN ship to engage the enemy in the Korean theatre of war.

HMCS Athabaskan conducts a patrol in the Yellow Sea off the west coast of the Korean peninsula.

While the main elements of North Korean forces were inland and out of range of naval gunfire, there were warehouses and other installations on the waterfront of the captured port of Yeosu on the southeast coast that might be of value to the enemy, even if the port itself was blockaded.

Cayuga and HMS Mounts Bay were given the job. The two ships steamed to within 6.5 kilometres of the port on Aug. 15, anchored, and prepared for action as if they were on the practice range instead of in enemy territory.

With an aircraft spotting, Mounts Bay began to methodically bombard the harbour area. About a half-hour later, Cayuga fired its first ranging shots. The pair bombarded the port continuously for almost two hours.

Cayuga alone placed 94 rounds of four-inch high explosive on the harbour installations before the pair broke off and returned to Sasebo to continue regular escort duties.

Though the target was far from completely destroyed, it marked the first time since the Second World War that the RCN engaged the enemy.

“It was only the first of many such actions,” reported the RCN history. “In the next three years Canadian destroyers were to carry out hundreds of bombardments and hurl thousands upon thousands of shells at the enemy.”

The two ships bombarded the port continuously for almost two hours.”

Alongside an American supply vessel, crew of HMCS Nootka replenish ammunition stores in June 1952.

The Canadians conducted blockade patrols and escorted ships supplying the attacking force at Incheon in September 1950, coming under inaccurate fire from shore batteries, which they quickly silenced.

In November, with UN forces deep into North Korea and Chinese troops joining the North Korean cause, the three Canadian ships were sent from Sasebo to patrol the North Korean coast.

Over the next month, the UN offensive would be stopped in its tracks, then crushed, by successive Chinese counteroffensives.

“As the full extent of the disaster that had overtaken the Eighth Army became apparent, orders went out to evacuate the port of Chinnampo and to make preparations for a withdrawal from Inchon as well, should this become necessary,” said the naval history.

Chinnampo was the port city for the North Korean capital of Pyongyang. It stood at the end of a long, well-mined channel and had the extreme tidal range typical of western Korea. UN ships had cleared a deep-water channel by the third week of November and the port was soon handling nearly 5,000 tonnes of cargo daily.

8

Number of Canadian warships that served in the conflict

Sailors aboard an ammunition barge (above) replenish Cayuga.

By December, however, the Chinese had backed U.S. troops to the water’s edge and an evacuation was ordered. On the night of Dec. 5, 1950, Cayuga led five other destroyers, including Athabaskan and Sioux, 32 kilometres up the narrow, shallow waters of the Taedong River toward Chinnampo.

One ship ran aground while a second got tangled in a mooring wire of an unlit buoy. Both had to turn back. The remaining four destroyers, under Cayuga’s lead, proceeded slowly and cautiously up the channel.

Lieutenant (N) Andrew Collier, Cayuga’s navigation officer, was the sailor responsible for ensuring the ship’s safe passage. Collier made 132 fixes that night, most of them by radar, showing the position of the ship in relation to the channel marker buoys and nearby landmarks.

A Second World War veteran, his navigational skills were credited with playing a large part in ensuring the operation’s success and he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his work.

Huron (above) spent some 70 days in dry dock after running aground during a “trainbusting” operation two weeks before the Korean armistice was signed

With the troops safely evacuated, the destroyers bombarded the port, destroying railway lines, dock installations and huge stocks of strategic materials that had to be left behind. The ships made a fighting retreat and cleared the channel the following day.

Collier, who joined the navy at 18, would retire in 1979 at the rank of vice-admiral and died in 1987 in Victoria at age 62.

The peninsula’s geography created a unique opportunity for the UN navies. Rail routes tended to run along the coastline, cut into the sides of the rugged Taeback Mountains along the peninsula’s east coast, often sheltered by tunnels.

The rail line was only within range of the UN warships in some areas. They were kept at a distance by shallow waters and North Korean coastal batteries. A ship would spot a train, then radio the vessel whose “guns were already loaded ready to fire,” said Ken Kelbough of HMCS Sioux. “The guns would level off and then foooom, foooom, blew them up.”

Then “we had to get out of there because they would bring up shore batteries and you’re a sitting duck on a ship.”

Huron was the first of the Canadian ships to target North Korean rail transport, in June 1951. But “trainbusting” became something of a sport for the competing allied navies after the USS Orleck destroyed two trains in two weeks in July 1952.

Refugees flee Pyongyang across a bombed-out bridge over the Taedong River in December 1950. The image earned photographer Max Desfor a Pulitzer Prize.

Their success was no fluke. The Canadians were careful hunters.”

It was declared trainbusting champion and a challenge was issued to beat the score. A ship could only claim a train if they destroyed the engine, regardless of how many rail cars were obliterated.

In one area, there was a series of five tunnels. “We caught a train between tunnels and destroyed all the boxcars,” recalled Norman Heide of Sioux. But without the engine, the ship received no credit toward the championship.

Smoke billows from a gun aboard a Canadian navy vessel as its crew prepares to reload (above)

Their success was no fluke. The Canadians were careful hunters.

“At night, in the dark, they’d shut down everything onboard the ship and just glide along the coast…listening to see if they heard a train or whistle,” recalled Daniel Kendrick of HMCS Huron. When they did, up went a star shell, flooding the coast with light so gunners could “hit it before it heads into a tunnel.”

In late October 1952, HMCS Crusader, a former Royal Navy destroyer, joined the Trainbusters Club. Within six months, the ship had won the title.

Lieutenant-Commander William J.H. Stuart and Able Seaman Eldon J. Davidge pore over a chart of the peninsula’s west coast on Crusader (above).

“We had some of the finest gunners in the Canadian navy,” said crewman Irving Larson.

Crusader’s first victim came on Oct. 28—a 13-car train and engine. HMCS Haida joined the club on Jan. 29, 1953, and scored its second hit on May 26.

In April, Crusader moved the bar higher, destroying three trains and engines within 24 hours. Two of the trains were running in opposite directions and Crusader took them out simultaneously.

HMCS Athabascan destroyed its first train on May 24, 1953.

Hitting a train “was quite an achievement truthfully because the ship is going up and down, you’ve got to get your guns…right exactly where the train is, or just below a bit, to destroy the track and knock it off. And it became quite a feat,” said Haida gunner Jim Wilson.

By war’s end, UN ships had destroyed 28 trains and their engines—eight of them by three Canadian ships. Athabaskan and Haida equalled Orleck’s tally, taking out two trains apiece. But Crusader ran away with the title, destroying four.

HMCS Iroquois was the only Canadian ship to suffer losses from enemy action during the Korean War. It came afoul of shore batteries on Oct. 2, 1952. Three sailors died and 10 others were wounded when a shell burst overhead.

Leading Seaman George Guertin

It took George Guertin two years to get to Korea after he joined the navy at 19 years old in 1951. His time there was short-lived, but eventful.

He sailed out of Halifax aboard HMCS Huron, a Tribal-class destroyer that had served with distinction in the Second World War.

Now it was spring 1953, and armistice talks aiming to bring Korean War fighting to an end were nearing a conclusion when Huron arrived in Sasebo, Japan. It was the vessel’s second Korean tour, and it came after an 18-month refit. They would stage three patrols out of the Japanese port.

Refit or no, life aboard the old Tribal-class ship was “rugged,” said Guertin, who served on seven Royal Canadian Navy vessels during 15 years in service. Like other RCN ships of the time, Huron had no air conditioning in the sweltering heat of a Korean summer.

Crew worked three watches—each four hours on, eight hours off. They slept in hammocks, 20 to a space smaller than a typical family room—“practically touching”—and ate in a cramped mess, mostly stews. “It was dirty living, terrible.”

A radar operator, Leading Seaman Guertin’s first taste of war came when Huron crew recovered the remains of an American aviator shot down in the Sea of Japan.

Huron had a go at “trainbusting,” but the ship was plagued by bad weather and they were in and out so quick, to avoid return fire from nearby shore batteries, that the crew never knew if they hit anything. “We’d go in in neutral, if you will—just slide in, turn broadsides, fire, and get the hell out of there before anything opened up,” said Guertin. The official records don’t attribute any train strikes to Huron.

The destroyer’s tour came to an abrupt end on the night of July 13, two weeks before the armistice was signed. The ship ran aground after a trainbusting operation off Yang-do Island, well up the North Korean coast.

Fortunately, fog had reduced Huron to 12 knots when it ran headlong into the island. “We were about 1,800 feet [550 metres] offshore when that happened. It was about 12 o’clock at night and the heavy fog hid us from the mainland. We knew there were gun positions in there.”

A shipmate, Daniel Kendrick, was sent down to assess the damage. “All I could see was big, black rocks and black water and a great big hole,” Kendrick told the Historica-Dominion Institute in 2013.

Crew lightened the bow, jettisoning both anchors and dragging the anchor cables back to the quarterdeck. Even a piano was dumped over the side.

At high tide, with the bow up, they eased the destroyer off the rocks. An American cruiser and aircraft carrier were standing by. A deep-sea tug towed the ship stern-first back to Japan. The usual 24-hour transit took four days.

“We were about 70 days in dry dock,” said Guertin. “When we came out, the war was over. We headed back to Halifax. We’d been gone 11 months. I was glad to get off that ship.”

By the fall of 1951, UN defences were established near the 38th parallel, the so-called Jamestown Line, some 40 kilometres north of Seoul and armistice talks had begun.

1st Commonwealth Division held some 12,000 metres between the U.S. 1st Cavalry Division on the right and the ROK 1st Division to the left. Commanded by a British Second World War veteran, Major-General Archibald James Halkett Cassels, it consisted of British, Canadian, Australian and New Zealand combat troops.

The Canadians held about 9,000 metres of north-south front, one of the last battlegrounds of the Korean War.”

The Canadians were supposed to have comprised a third, or a brigade, of the three brigades. But the 28th Commonwealth and the 29th British brigades were under-strength, so the 25th Canadian Infantry Brigade was contributing three of the seven line battalions—2nd Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment (RCR); 2nd Battalion, Royal 22e Régiment (the Van Doos); and three companies from the 1st and 2nd battalions of the PPCLI. In addition, each Canadian battalion had all four rifle companies up, or about half of the line infantry and almost two-thirds of the divisional front.

The Royal Canadian Horse Artillery (background) scopes out enemy positions along the 38th parallel in this piece by artist Joan Wanklyn. Paul Tomelin photographed survivor John Lewis (above) after the Chinese attack on ‘B’ Company, 1st Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment at Little Gibraltar.

They were supported by the howitzers of 2 Royal Canadian Horse Artillery (RCHA) and the 76mm-armed Sherman tanks of ‘C’ Squadron, Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians).

The Canadians held about 9,000 metres of north-south front. The land dropped suddenly some 75 metres in front of their positions to a small stream flowing south to the Samichon River, one of the last battlegrounds of the Korean War.

The dominant peak in the region was Hill 355. Known as “Kowang-San” to the Koreans, it was dubbed “Little Gibraltar” by American troops. It was the highest feature in the UN lines west of the Imjin River five kilometres to the south. Hill 355 and Hill 227, 1,500 metres to the west, were held at the time by the 1st Battalion, the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry of the British 28th Infantry Brigade.

8,123

Peak Canadian Army strength (at any one time) in the Far East, reached in January 1952