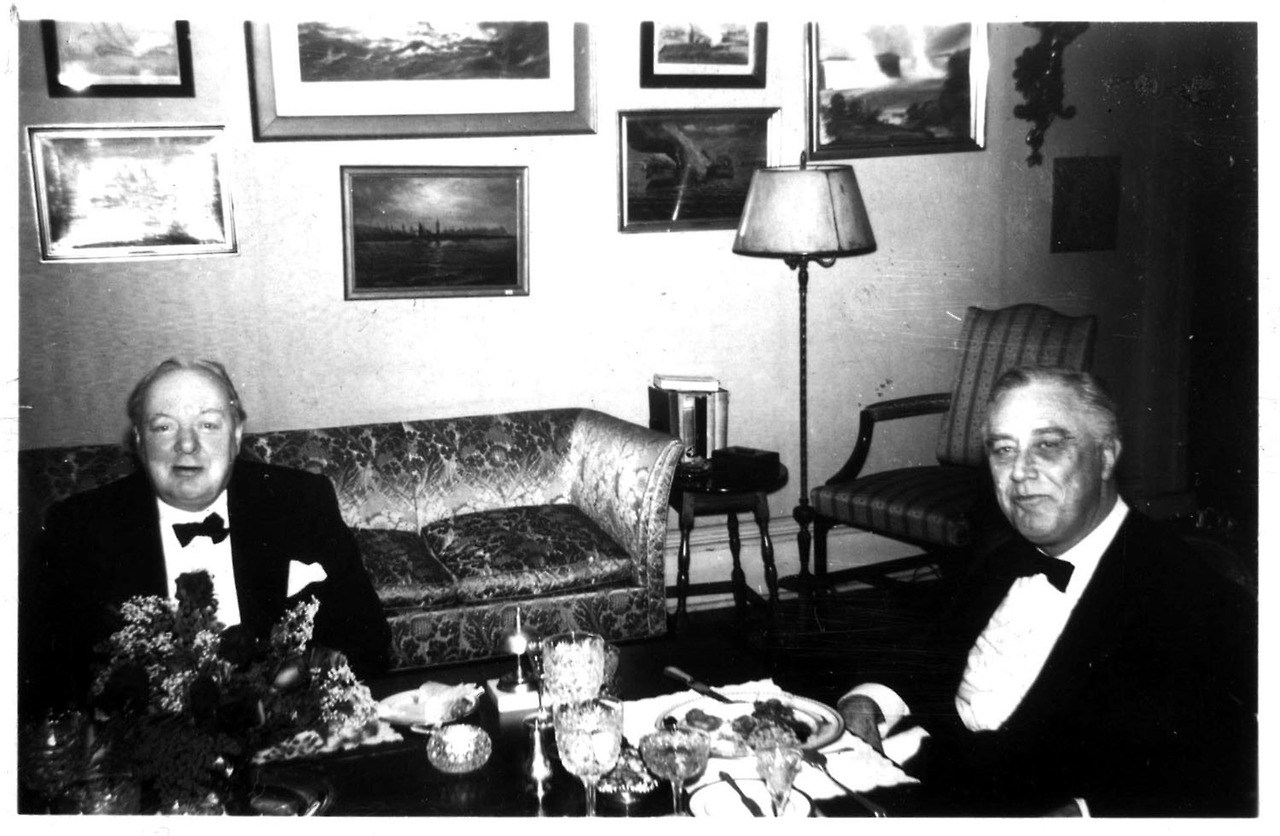

In December 1941, just days after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, United States president Franklin Delano Roosevelt informed his wife Eleanor that a guest, or guests, would be coming to stay at the White House.

“He told me I could not know who was coming, nor how many, but I must be prepared to have them stay over Christmas,” Eleanor Roosevelt wrote years later in The Atlantic. “He added as an afterthought that I must see to it that we had good champagne and brandy in the house and plenty of whiskey.”

Make that Pol Roger champagne, vintage Hine brandy and Johnny Walker Red—for the guest, of course, was Winston Churchill, the British bulldog prime minister whose eccentricities and fondness for libation are the stuff of legend.

“I must have a tumbler of sherry in my room before breakfast,” Churchill told the butler upon arriving at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, “a couple of glasses of scotch and soda before lunch and French champagne, and 90-year-old brandy before I go to sleep at night.”

A brilliant orator, Nobel Prize-winning writer, masterful politician and razor-sharp wit, Churchill once said that when he was younger he “made it a rule never to take strong drink before lunch. It is now my rule never to do so before breakfast.”

The 67-year-old leader stayed with the Roosevelts for a month. White House staff often saw him in a one-piece romper suit or a Chinese silk gown, complete with dragon. Sometimes he wandered the halls in far less.

“We live here as a big family in the greatest intimacy and informality,” Churchill wrote British Labour Party leader Clement Attlee.

On Dec. 30, he delivered his “some chicken; some neck” speech in Canada’s House of Commons after taking the train to Ottawa, pausing impatiently outside the chamber afterward for Yousef Karsh.

It was then that the legendary portraitist snatched the cigar from Churchill’s mouth, eliciting what is probably history’s most famous glower. The photograph came to represent Britain’s stubborn defence against Hitler’s relentless advance.

“Daytime was a prelude to his deepest work hours, from dinner long into the night,” Erick Trickey wrote for Smithsonian. “He kept Roosevelt up until 2 or 3 a.m. drinking brandy, smoking cigars and ignoring Eleanor’s exasperated hints about sleep.”

“It was astonishing to me that anyone could smoke so much and drink so much and keep perfectly well,” the first lady wrote.

“When I was a young subaltern (junior officer) in the South African War, the water was not fit to drink,” he once explained. “To make it palatable we had to add whisky. By diligent effort, I learned to like it.”

And like it a lot. As a 25-year-old soldier during the 1899 war in Sudan, he wrote 13 front-line columns for The Morning Post, a conservative London daily. He brought along 36 bottles of wine, 18 bottles of aged scotch and six bottles of vintage brandy for the task.

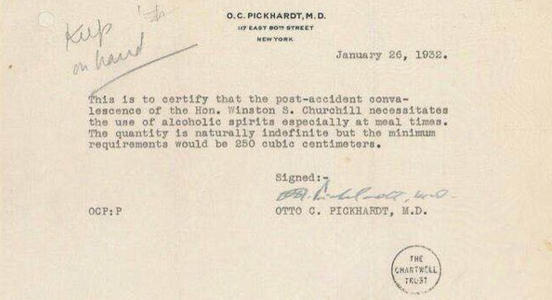

During a Prohibition-era trip to the United States, Churchill was knocked down by a car in New York. The doctor attending him, Otto C. Pickhardt, issued a medical note saying Churchill’s convalescence “necessitates the use of alcoholic spirits especially at mealtimes.”

The quantity, his physician prescribed in clear type, “is naturally indefinite, but the minimum requirements would be 250 cubic centimeters,” or almost six shots—per meal.

In 1936, his wine merchant’s tab was reportedly today’s equivalent of $75,000. His lifetime Pol Roger consumption alone has been estimated at 42,000 bottles.

Indeed, it was Churchill who declared: “Remember gentleman, it’s not just France we’re fighting for, it’s champagne!”

Author William Manchester once rejected the suggestion that Churchill drank too much. “Churchill is a sensible if unorthodox drinker,” he said. “There is always some alcohol in his bloodstream and it reaches its peak in the evening after he has had two or three scotches, several glasses of champagne, at least two brandies, and a highball.”

Professor Warren Kimball of Rutgers University, who has written extensively on Churchill and Roosevelt, maintains Churchill was “alcohol-dependent.”

“He was not an alcoholic,” insisted Kimball. “No alcoholic could drink that much!”

Hosting a summit with Churchill and Roosevelt in August 1943, teetotaling Prime Minister Mackenzie King griped that his British counterpart was “tight all the time.”

In his memoir, I Never Made Love in a Canoe, former army sergeant and wartime Maple Leaf reporter George Powell relates the story of a dinner at Churchill’s home for which then-prime minister John Diefenbaker and his wife were the primary guests.

Diefenbaker, too, did not drink. But, he told Powell, he couldn’t help but notice with some surprise as they sat down to eat that there was nary a sign of alcohol anywhere. He dismissed the matter until he noticed Churchill making repeated sliding movements to his right, accompanied by a sort of “slouch.”

“I thought it might be some affliction we hadn’t heard about,” he told Powell, “or perhaps something as simple as handing tidbits to a dog or cat that I hadn’t noticed, under the table.”

Diefenbaker began averting his eyes whenever Churchill made the move, until once he looked back too soon and caught his host raising a “vial—half-filled with brandy—to his lips. He’d kept his supply in the side of an unlaced boot!”

“I admit, I positively stared, transfixed by the sight, and perhaps marvelling a bit, too, at the man’s ingenuity. Then our eyes met and, still holding the vial at-the-ready, he said to me, ‘Prime Minister, I understand you are a prohibitionist.’”

Diefenbaker realized there and then that Churchill had acted out of concern that he might offend his guest.

“No, sir, I’m afraid you have been misinformed,” he told Churchill. “I am not a prohibitionist, I am a teetotaler.”

“That famous twinkle crept into Winston’s eyes as a cherubic grin lit his face,” Diefenbaker told Powell. “‘Ah,’ he chortled, ‘that is good news—for you thus harm no one but yourself!’ And with that he downed his brandy in a draught.”

“Winston, you are drunk,” declared Labour MP Bessie Braddock, a long-time adversary, “and what’s more you are disgustingly drunk.”

“Bessie, my dear, you are ugly,” came Churchill’s retort, “and what’s more, you are disgustingly ugly. But tomorrow I shall be sober and you will still be disgustingly ugly.”

In fact, Churchill was not drunk, Golding said, just tired and wobbly, which no doubt contributed to his merciless salvo.

Furthermore, the quote was not wholly his own. He borrowed it from W.C. Fields, who replied to a similar accusation in the 1934 movie It’s a Gift: “Yeah, and you’re crazy. But I’ll be sober tomorrow and you’ll be crazy the rest of your life.”

After the Yalta Conference in February 1945, Churchill visited King Ibn Saud, the founding father of Saudi Arabia, at an oasis in Egypt. Word was passed along that neither tobacco nor alcohol were permitted in his majesty’s presence.

“Winston informed the interpreter that if it was the religion of His Majesty to deprive himself of smoking and alcohol he must point out that his rule of life prescribed as an absolutely sacred rite, the smoking of cigars and the drinking of alcohol before, after, and, if need be, during all meals and in the intervals between them,” Langworth wrote in his 2017 book Winston Churchill: Myth and Reality.

“The King graciously accepted the position, and his own cup bearer even offered the Prime Minister a glass of water from the sacred well of Mecca—‘the most delicious that I have ever tasted,’ said Winston—which, for him, was going quite a long way.”

Pol Roger placed a black border around the labels of Brut NV shipped to the United Kingdom after Churchill died in 1965 at the age of 90. In 1984, it released its Cuvée Sir Winston Churchill—an homage, it said, “mindful of the qualities that he sought in his champagne: robustness, a full-bodied character and relative maturity.”

The first of the 10-year-old vintages was released only in magnum (1.5-litre) format.

Order this quote poster of Sir Winston Churchill for only $6.99! SHOP NOW

Advertisement