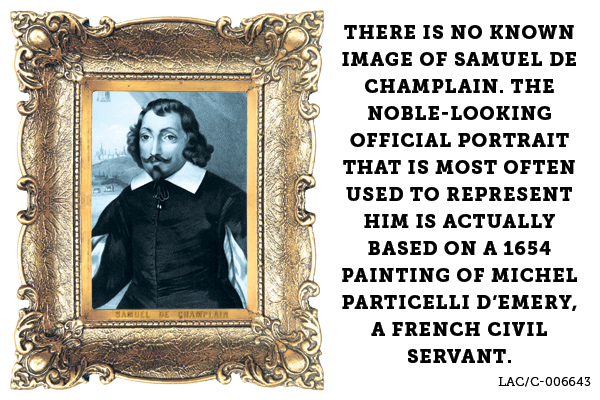

Most of us have experienced bad winters—record-breaking temperatures, snow up to the roof, winters that refuse to end. But few of us have known winters as bad as those of Samuel de Champlain.

The winter of 1604-05 was spent at Sainte-Croix. It was extremely cold, unlike anything Champlain or his men had seen in France, and scurvy ravaged their ranks. The severe temperatures exacerbated the weariness, sore limbs and swollen, bleeding gums brought on by a lack of vitamin C. The following winter was just as bad, and once again scurvy was a factor.

While preparing for the winter of 1608, Champlain discovered that five of his company had been hired by the Spanish and Basques to murder him. Champlain confronted Antoine Natel, one of the conspirators, who confessed, revealing that the company locksmith, Jean Duval, was the ringleader. A trial was held, the first known trial in North America. Natel was pardoned but Duval was hanged, then beheaded, his head exhibited on a stake in the new colony as a deterrent.

The winter proved more dangerous than the Spanish; 16 of Champlain’s 25 men died of scurvy or dysentery over those frigid months. Their bodies lying frozen until spring when the ground was soft enough to dig.

Winter remained an issue for the next two decades. The winter of 1627-28 also claimed the lives of settlers. But it was the following winter that proved to be Champlain’s worst. He was expecting new settlers and fresh provisions from France. In 1628, several ships sailed from Dieppe, carrying 200 settlers and much-needed provisions. But before they could reach New France, they were intercepted by an English force led by the Kirke brothers. Champlain had been counting on those supplies to survive the winter. When one of the Kirkes demanded the surrender of Quebec, Champlain boldly refused, despite their depleted state and limited ammunition. His bluff worked and Kirke retreated, sailing back to England. But the winter in Quebec was harsh and food was scarce.

Even worse than the miserable winter was the fact that in the spring, the English returned and Champlain was now forced to surrender. His life’s work given over to the hated English. All the residents of New France were deported, sent back to the mother country. Champlain returned to Europe and discovered that the war between England and France (that particular war at any rate) had ended before the surrender of Quebec, making Kirke’s seizure illegal, an act of piracy rather than war. Quebec was finally returned to the French, and Champlain returned to New France, though without his young wife. She had decided that she could no longer endure either the winters or her husband.

Fittingly, Champlain died in winter—on December 25, 1635, in Quebec City.

Celebrate 150 years of Canadian history with our latest Special Issue O Canada!

On newsstands now!

Advertisement