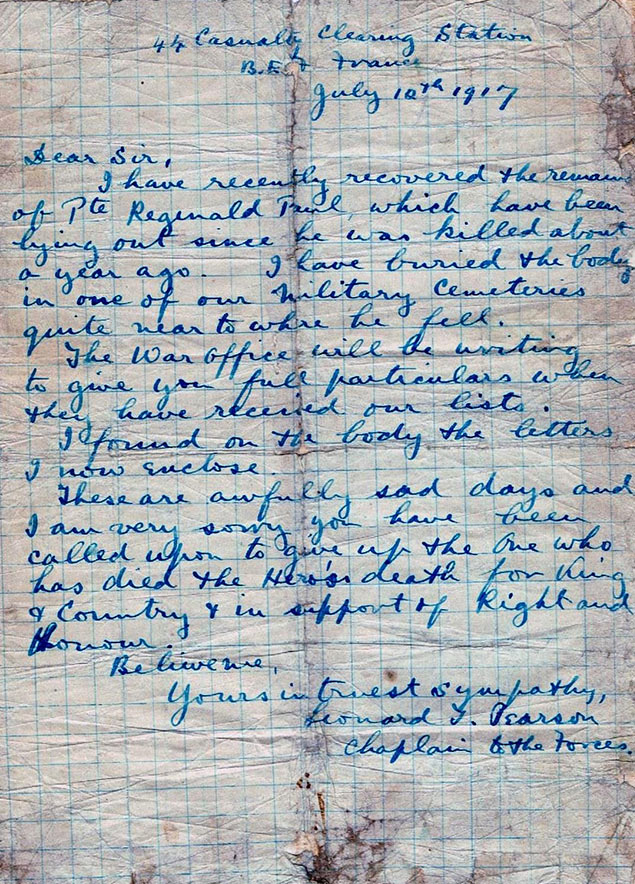

Written by the chaplain to the forces, Leonard T. Pearson, it’s dated July 10, 1917.

There’s no destination address recorded on the page, but the recipient was William John Paul of Burin, Nfld., a merchant and father of Private Reginald Paul.

Twenty-one-year-old Reginald had been a member of the storied Newfoundland Regiment. He was killed on the first day of battle at the Somme—July 1, 1916. A day venerated by Newfoundlanders.

“Dear Sir,” Pearson begins, “I have recently recovered the remains of Pte Reginald Paul, which have been lying out since he was killed about a year ago. I have buried the body in one of our military cemeteries quite near to where he fell.

“These are awfully sad days and I am very sorry you have been called upon to give up the one who has died the Hero’s death for King and Country & in support of Right and Honour. Believe me.”

The young storekeeper and carpenter, regimental No. 731, was among 324 Newfoundlanders killed in mere minutes at Beaumont-Hamel on that first morning of one of history’s most notorious battles. Another 386 Newfoundlanders were wounded. Just 68 members of the regiment answered roll call the next morning.

In less than five months on the Somme, Allied forces suffered 620,000 casualties, including 72,000 British and Empire troops who died with no known grave. The Germans took at least 434,000 casualties.

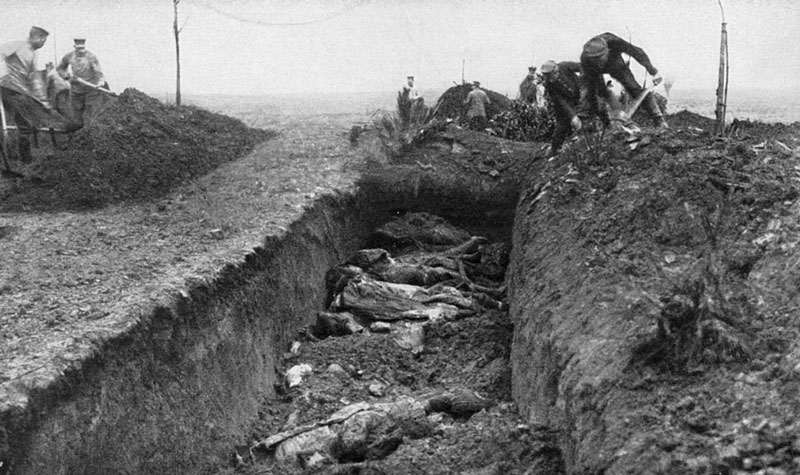

And like so many other battles before and since, the dead lay out for long periods, at least until after the fighting moved on. It seems especially true of the First World War with its stagnant combat and ground pummeled by repeated artillery barrages.

In his brief military career, Reginald Paul saw all of two days of combat, and he was hit both times.

He had been wounded on Sept. 20, 1915, the regiment’s first day in Gallipoli—a theatre of war which was, for Australians in particular, another slaughterhouse. Paul took shrapnel in the right arm and shoulder from a Turkish artillery shell.

After hospital stays aboard ship, in the Greek isles, and on Malta, he reunited with his regimental mates in Egypt.

“Each body was covered inches deep with a black fur of flies, which flew up into your face, into your mouth, eyes and nostrils as you approached.”

In March 1916, they sailed for France and, ultimately, the Somme. The Newfoundland Regiment, which would receive its “Royal” designation almost two years later, was in the third wave to go over the top at Beaumont-Hamel, a Picardy commune nestled among the chalk uplands and ridges north of the Ancre River.

Paul was immediately listed as missing in action. It would be six months before he was officially designated “presumed dead.”

“Your Son’s poor Body was one of over 6,000 that I helped to recover as soon as the Enemy retreated & the ground safe to work over,” Pearson wrote Paul’s bereaved father again in November 1917.

It was a year after the battles of the Somme ended with no clear winner and without the breakthrough for which its chief architect, Field Marshall Douglas Haig, had hoped. History would remember Haig as “The Butcher of the Somme.”

“I have looked up my Records & find I buried his Remains in Hawthorne Ridge, No 2, B Row, Grave 8. It is quite close to Beaumont Hamel, between the wires in the original ‘No Man’s Land’ & within a few yards of where he fell,” said Pearson.

“The Record book has to be carefully gone through by the War Office as 95% of the bodies I recovered are cases of ‘Missing’. It is only within the last few weeks the official news has been sent to some relatives and probably you will be hearing quite soon again.”

Truth is, death in war was never glorious. The 1914-18 conflict brought that home as no other before it.

This, despite the censors’ best efforts. In his book The Censored War: American Visual Experience During World War Two, historian George H. Roeder wrote that “the most striking images to come out of World War I were written ones.”

“This remained true even when the lifting of censorship after the war allowd (sic) the release of gruesome photographs of mutilated and rotting corpses.”

No photograph, Roeder said, had the power of a description like that of British officer Stuart Cloete who, years after the war, described collecting remains on the Somme battlefield at Serre following an attack by “green, badly led troops who had too big a rum ration … against a strong position where the wire was still uncut.”

“As you lifted the body by its arms and legs, they detached themselves from the torso, and this was not the worst thing,” he wrote. “Each body was covered inches deep with a black fur of flies, which flew up into your face, into your mouth, eyes and nostrils as you approached. The bodies crawled with maggots.”

“The birds disputed the bodies with us…. We stopped every now and then to vomit.”

The quality of photographs had improved by the century’s Second World War, but that did not diminish the power of the mighty word.

Said Roeder: “During World War II, newspaper and magazine editors and government censors kept tighter restrictions on pictures than on words despite this ability of words to disturb.”

One reason was practical: authorities could screen film and other items taken out of a war zone; they couldn’t control the memory banks of those who were there.

Another reason was fundamentally flawed: they assumed most of the general public would be more likely to process and remember what they saw in a photograph than what they read on the proverbial page.

“It was an appalling job. Some had been lying there for months and the bodies were in an advanced state of decomposition.”

The post-mortem fates of those killed in action (KIA) depended largely on the manner and circumstances of their deaths. The Ypres Salient Falkirk District War Dead website groups those killed in action in three categories:

- identifiable remains buried close to the front, including those killed by snipers or explosions; collapsed mine, trench and dugout victims; wounded medical evacuees who died on the way out;

- those less easily identifiable, but likely buried in cemeteries or burial plots near the firing line, including KIAs whose bodies could not be immediately recovered because the area was under fire or those killed during a rapid advance and picked up by other units;

- the unidentifiable. “Fragments of men, once found, would be buried if possible,” says the site. “Many men were simply not found, although post-war battlefield clearance reduced the total of missing.”

In a widely quoted account, East Lancashire Lieutenant Paddy King describes leading a burial party to the Frezenberg Ridge in Belgium, where they were to bury the remains of successive waves of soldiers killed over two months of fighting into September 1917. The recovery squad stocked up on empty-sandbags, rubber gloves and extra rum rations on the way out.

“They were mostly Scottish soldiers—Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders and Black Watch,” King said. “It was an appalling job. Some had been lying there for months and the bodies were in an advanced state of decomposition; and some were so shattered that there was not much left.

Many remains ended up interred in those sandbags. The burial party marked the graves of those who still had identity discs—dog tags in American parlance—and added them to a list with a map reference.

“Where the bodies were so broken up or decomposed that we couldn’t find an identity we just buried the man and put ‘Unknown British Soldier’ on the list. It was a terrible job. The smell was appalling and it was deeply depressing for the men.”

The battle had moved on and the ground was pummeled into a mass of detritus, mud and water. They could see nothing but two abandoned pillboxes.

“There was no sign of civilisation. No cottages, no buildings, no trees. It was utter desolation. There was nothing at all except huge craters, half the size of a room.

“They were full of water and the corpses were floating in them. Some with no heads. Some with no legs. They were very hard to identify. We managed about four in every 10.”

The job took them two days. They committed each set of remains formally to their grave and said a prayer from the issue prayer book: “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.”

“The men all stood around and took their hats off for a moment, standing to attention. ‘God rest his soul.’ A dead soldier can’t hurt you. He’s a comrade. That’s how we looked at it. He was some poor mother’s son and that was the end of it.”

Thousands of small burial plots were hurriedly created on or near the battlefields. They were often damaged by shellfire. In 1918, says the Falkirk site, many were overrun, first by advancing enemy and later by the Allies pushing eastward again.

Plots were destroyed by shelling, and the locations of many registered and otherwise documented graves were obliterated.

Unidentifiable remains were buried as unknown soldiers, the markers of Empire and subsequent Commonwealth dead engraved with the words “known unto God.”

The search parties, known as exhumation companies, looked for clues suggesting remains might be thereabouts—protruding rifles or stakes bearing helmets or equipment; partial remains, small bones or kit brought above ground near ratholes; even vivid green grass, darkened soil or greenish-black water.

“Remains once discovered were put onto cresol soaked canvas for a careful identification,” said the Falkirk site, referencing an industrial chemical used as a disinfectant. “If any uniform remained, pockets were searched and badges and buttons identified. If a Scottish soldier was found, the tartan was recorded.

“Next they looked for identification discs and personal effects: watches sometimes had useful inscriptions, for example. Sometimes knives, forks and spoons that had been placed down the puttees carried the man’s name, initials or number.”

The searchers checked for names or numbers stenciled into webbing. Officers could be identified as such by their breeches and privately purchased boots. Where possible, dental details were recorded and investigated.

The remains would be reburied in a cemetery.

Unidentifiable remains were buried as unknown soldiers, the markers of Empire and subsequent Commonwealth dead engraved with the words “known unto God.”

The phrase was chosen by British poet Rudyard Kipling, who was working with what was then called the Imperial War Graves Commission, predecessor to the Commonwealth commission, or CWGC.

The origin of the phrase is unknown, but it has been linked to sections of the King James Bible. It was used through the Second World War and appears on more than 212,000 gravestones worldwide.

Typically, white or grey, the uniform stones of Empire and Commonwealth war dead are readily recognizable—more than 1.1 million of them at more than 23,000 locations in 150 countries and territories.

The unit badge appears at the top of the marker if it’s known. Under it, the first line of text on markers of unidentified dead is often the simple phrase “a soldier of the Great War.” In the middle is a cross, though the dead’s actual religious affiliation, if any, may be unknown. “Known unto God” appears at the bottom.

Human remains are still being recovered from historic battlefields to this day, some of them identifiable through DNA and other analysis.

—

Read about a recently discovered war grave in the Front Lines column “Archeologists, veterans uncover soldier’s remains at Waterloo.”

Advertisement