Captain Dyess’s abbreviated service in the U.S. Army Air Force and elsewhere was more eventful than any Hollywood script could credibly imagine.

The Texas native volunteered to stay in the Philippines and fight the overwhelming Japanese advance on Bataan, serving both as a fighter pilot and an infantryman; he was taken prisoner and survived the Bataan Death March of April 1942, then endured a year of starvation and brutality in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps before he escaped, joined a Filipino guerilla force and fought in the jungle for three months.

Now a major, Dyess was evacuated by submarine in July 1943, taken to Australia and returned to the United States a hero, his awards including two Distinguished Service Crosses, two Silver Stars and two Distinguished Flying Crosses.

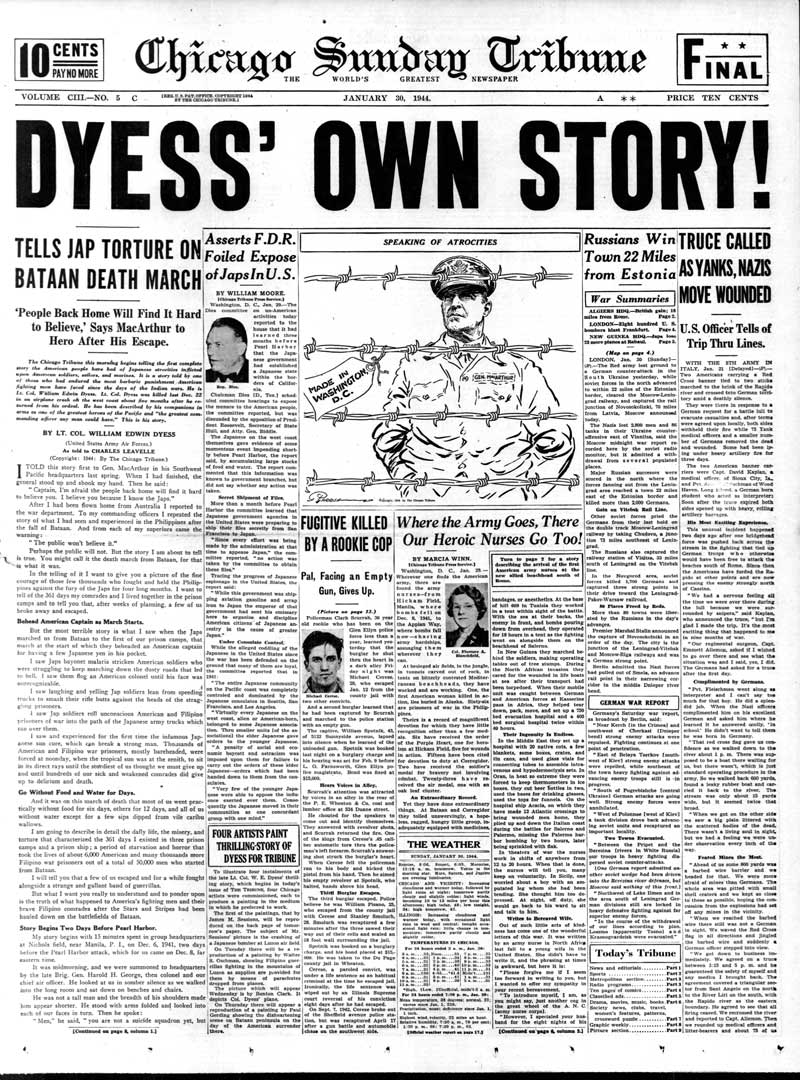

But it was Dyess’s exposé, the first victim’s account of the death march and the abuse of PoWs by their Japanese captors, that opened American, Canadian, British and Australian eyes to the horrors confronting their servicemen after the defeats at Hong Kong, Bataan and Corregidor.

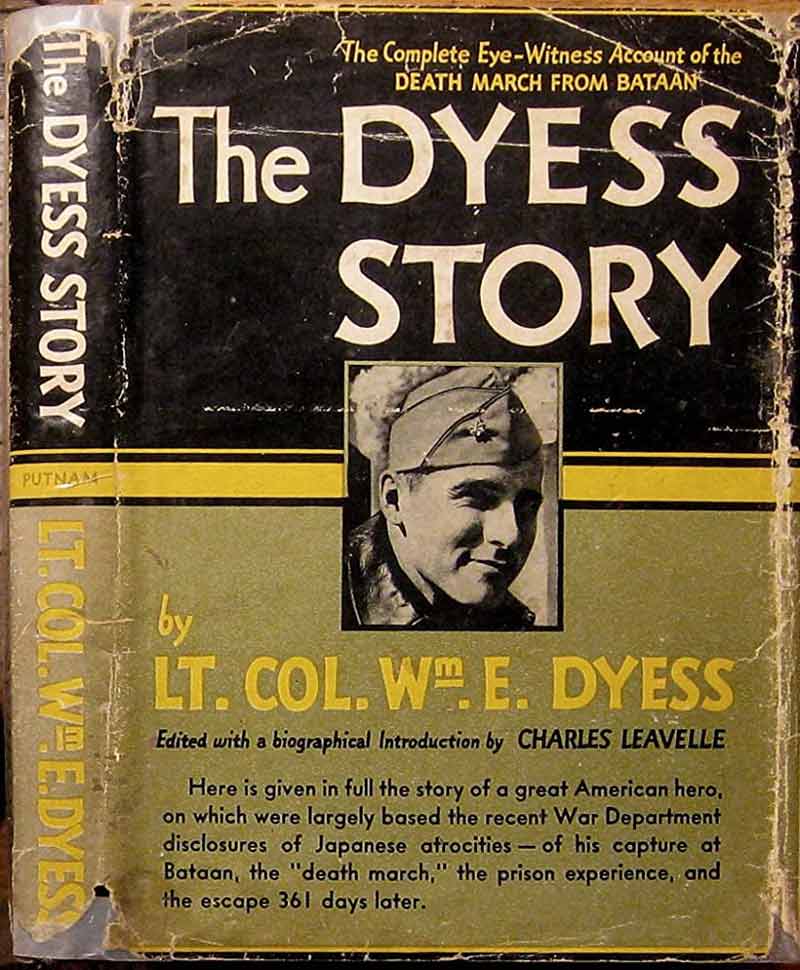

Dyess emerged from it all a lieutenant-colonel, but he would not live to see his book, The Dyess Story, or the Chicago Tribune’s series of 25 syndicated articles published. He was killed in a December 1943 plane crash in California, just a month before Washington lifted its ban on his story.

“The story of the capture, imprisonment experience, and escape of Dyess and the other escapees from Davao opened up new plots that did not shy away from the ideas of defeat and abandonment. Indeed, these less flattering accounts featured prominently. As such, it undermined an overall narrative of American victory—which explains its exclusion from official military accounts.”

Dyess was nominated for a Medal of Honor after he died, but was instead posthumously awarded the Soldier’s Medal for sacrificing his life by “crash landing his airplane in a small vacant lot in order to avoid hitting civilians traveling on a broad road where a comparatively safe landing could have been made.”

Efforts to get him America’s highest award for gallantry continue today, primarily in the form of a petition seeking to “remedy a seventy-year-old injustice.”

Food and clean water were scarce and U.S. troops soon resorted to eating their horses and wildlife.

The Canadian and British defenders of Hong Kong were among the embattled when, in December 1941, Japanese forces began to push southward toward New Zealand and Australia. Both the invasions of the Philippines and Hong Kong began on Dec. 8, 1941, hours after the Dec. 7, attack on Pearl Harbor, on the other side of the international date line.

Japan had been fighting the Second Sino-Japanese War with China since 1937 and already occupied Manchuria and other parts of China, Taiwan and Korea.

The Philippines would serve as a staging area, a jumping-off point for Japanese campaigns in resource-rich Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. Outnumbered 3:2, the battle-hardened Japanese nevertheless swiftly overran most of Luzon in the first month of fighting. American and Filipino forces withdrew to the Bataan peninsula, where the Japanese held them under siege for 40 days.

Poorly supplied and underarmed, Allied resources were quickly depleted. Food and clean water were scarce and U.S. troops soon resorted to eating their horses and wildlife.

Dyess was commanding the 21st Pursuit Squadron, its ranks gutted in the initial Japanese attack. Flying the P-40 Warhawk fighter, he had led his unit against the Japanese amphibious landings on Bataan.

After two weeks of bitter fighting, Dyess led 20 men in a daring seaborne raid that wiped out a particularly stubborn group of Japanese entrenched in the seaside cliffs on Feb. 8, 1942.

Dyess had shot down five Japanese aircraft when word came that three 2,000-ton tankers and transports, a cruiser and several destroyers had pulled into Subic Bay on the west coast of Luzon Island. Now ground crew had jury-rigged a Warhawk for a different job. It was March 3.

“Ed took a P-40, hung a 500-pound bomb onto its belly, and started out to bomb and strafe the Japs,” Lieutenant Ben Brown told Byron Darnton of the New York Times in 1942. “He made three trips. I was his relief pilot, but he wouldn’t let me fly. He did it all himself.

“He missed the ships with this bomb but hit a small island on which supplies were stored and blew them up. By strafing, he blew up one 2,000-ton ship, beached another, and sank two 100-ton launches. And he strafed troops and docks and caused a lot of casualties.”

“We were shooting everything edible. Before the end, there was hardly a monkey left alive in the area.”

Running low on airplanes, he led and trained those who remained as riflemen and converted the unit to a temporary company of the 71st Infantry Division.

“Those of us who trained as infantry were willing, but awkward,” Dyess would later write. “For nearly two weeks before we saw real action we charged up and down mountains and beat the bush for Japs. We were bivouacked in a canyon in southern Bataan and had all sorts of terrain nearby for practice.

“Our equipment looked as though it might have been picked up at an ordnance rummage sale.”

Their weapons included .50-caliber machine guns salvaged from the P-40s and equipped with homemade mounts and six Lewis aircraft .30-calibre machine guns, which they fired looped over the shoulder, holding the barrel with an asbestos glove.

“Our menu soon became as varied and slumpy as our armament…we were shooting everything edible. Before the end, there was hardly a monkey left alive in the area. We even ate lizards, though these fleet reptiles were hard to bag.”

They didn’t even have entrenching tools and, during their first confrontation with the Japanese, they had to conduct the fighting on ground level or from behind trees. They had been told they were facing 30 enemy; the actual number turned out to be in the hundreds. They were under siege and “casualties ran high.”

“Before those seven sleepless days and nights had ended we were so weary, dirty, and starved we didn’t care whether we were shot or not.”

As reinforcements arrived and the battle neared its end, pockets of Japanese were boxed in along the cliffs. The airmen draped sheets over the bluffs to mark the enemy positions, then took to small navy boats to direct fire by ships offshore.

Dyess was aboard a small gunboat. Fragmentation bombs dropped by Japanese aircraft were exploding all around them. “One of the whaleboats was hit, then one of the gunboats,” he wrote. “In another minute the second whaleboat was gone.”

Dyess’s gunboat was almost at the beach when it was demolished by a near hit.

“But our shelling had been so deadly it was an easy matter for our survivors to storm the remaining Japs and mop them up. We finished this task at noon, taking only one prisoner.

“We counted more than 600 Jap bodies in the jungle, in the ledge, and on the beach. Many others were carried away by the sea. And we had been sent after only thirty! That night in our old bivouac area we slept like the dead.”

“Ed gave orders for all of his pilots to leave. But he refused to go himself.”

What was left of the 21st Pursuit Squadron was subsequently re-formed along with remnants of other units. They had 10 planes, just five of which were P-40s. The others were what Dyess described as “boneyard ships” and distributed over two airfields in what was dubbed “the Bamboo Fleet.”

For the rest of February through March and up to the fall of Bataan in early April, they flew reconnaissance, brought in medical supplies from the southern islands, and dropped supplies to guerrillas fighting in the mountains of Luzon.

They lived in bamboo shelters and ate what they could muster. “The life expectancy of anything that walked, crawled, or flew on lower Bataan was practically nil.”

It was during this period that Dyess launched his solo attack on Japanese shipping.

Within weeks, however, defeat was imminent for the American and Filipino holdouts.

“The time came when we had to get out of Bataan,” said Brown. “We had only a few planes left and the jig was up. Ed gave orders for all of his pilots to leave. But he refused to go himself.

The commander of Allied forces in the Philippines, the flamboyant General Douglas MacArthur, had left the island of Corregidor on March 11, ceding his command to General Jonathan Wainwright and uttering the prophetic words “I shall return.”

Dyess gave his plane, “Kibosh,” to Lieutenant Jack Donaldson and stayed, relinquishing his seat on the last plane out to the future president of the United Nations General Assembly, Colonel Carlos Romulo of the Philippine army.

“The captain’s head seemed to jump off his shoulders. It hit the ground in front of him and went rolling crazily from side to side.”

Dyess was captured by the Japanese on April 9, 1942, north of Mariveles, Bataan.

The Americans tried to rid themselves of any booty, mementoes and other Japanese items before they were searched by their captors.

At one point, a diminutive Japanese private was going through an air force captain’s pockets when he found Japanese yen. A large officer was standing nearby. The private held up the money, ducked his head, and sucked in his breath.

“The big Jap looked at the money,” an eyewitness told Dyess. “Without a word he grabbed the captain by the shoulder and shoved him down to his knees. He pulled the sword out of the scabbard and raised it high over his head, holding it with both hands. The private skipped to one side.

“Before we could grasp what was happening, the black-faced giant had swung his sword. I remember how the sun flashed on it. There was a swish and a kind of chopping thud, like a cleaver going through beef.

“The captain’s head seemed to jump off his shoulders. It hit the ground in front of him and went rolling crazily from side to side between the lines of prisoners. The body fell forward. I have seen wounds, but never such a gush of blood as this. The heart continued to pump for a few seconds and at each beat there was another great spurt…The white dust around our feet was turned into crimson mud.”

“This was the first murder,” Dyess wrote. “In the year to come there would be enough killing of American and Filipino soldier prisoners to rear a mountain of dead.”

A day later, he and some 75,000 other American and Filipino PoWs began the forced march of up to 112 kilometres to points north. At the outset, they hadn’t eaten in four days, the dust was choking, and the sun was blistering hot.

He described encountering a bombed-out field hospital where wounded Americans, many of them missing limbs, were stumbling aimlessly about. The Japanese forced them into the procession. Many couldn’t keep up.

“The Japs forbade us to help these men. Those who tried it were kicked, slugged, or jabbed with bayonet points by the guards who stalked us in twos and threes.”

Eventually, the hospital survivors fell back in the line. Dyess documented how the Japanese would shoot stragglers, even those who tried to help them. “The bodies were left where they lay, that other prisoners coming behind us might see them.”

Eventually, an English-speaking Japanese guard spoke to Dyess. “Sleepee?” he asked. “You want sleep? Just lie down on road. You get good, long sleep!”

That was the first 24 hours of a five- to 10-day march, depending on where PoWs were imprisoned.

Of the estimated 80,000 prisoners who began the journey, only 54,000 were present at the last stop, Camp O’Donnell. Estimates of Filipino dead range between 5,000 and 18,000; American dead numbered 500-650.

They died from exhaustion, disease, starvation, dehydration, beatings, shootings, bayonettings and beheadings.

One week the death rate at Camp O’Donnell was 20 Americans and 150 Filipinos a day; after two weeks it was 50 Americans and 500 Filipinos a day.

Dyess’s incarceration began at Camp O’Donnell in Capas, northern Philippines. He was later transferred two-and-a-half hours east by truck to Cabanatuan and, by Nov. 7, 1942, he was at the Davao Penal Colony on the Philippine island of Mindanao.

A Filipino-Japanese boy stood alongside the dais and interpreted as the camp commandant, a captain, spoke to the newly arrived prisoners at O’Donnell.

“Captain, he say you not prisoners of war,” the boy told them. “You are sworn enemies of Japan. Therefore, you will not be treated like prisoners of honorable war. Captain, he say you will be treated like captives.

“He say you do not act like soldiers. You got no discipline. You do not stand at attention while he talk. Captain, he say you will have trouble from him.”

The atrocities and torment continued, and escalated. Prisoners who weren’t killed or sent to Japan to perform slave labour withered away. Many were worked to death. One week the death rate at Camp O’Donnell was 20 Americans and 150 Filipinos a day; after two weeks it was 50 Americans and 500 Filipinos a day.

“Starvation was everywhere,” wrote Dyess. “Men who had weighed two hundred pounds or so now weighed ninety or less. Every rib was visible. They were living skeletons, without buttocks or muscle.”

Japanese reports acknowledged at least 1,555 Americans died from disease in the Philippine camps—mainly untreated malaria, dysentery and beriberi.

“The Japs provided no medicine,” wrote Dyess. “American doctors who were prisoners in the camp were given no instruments, medicines, or dressings. They were not allowed sufficient water to wash the human waste from the sick and dying men.

“When all ‘hospital’ space was gone many American soldiers lay out in the open, near the latrines, until they died…. There were flies by the millions.”

At Cabanatuan, “it was not uncommon that twenty per cent of each detail would die on the job in a day or in the barracks that night. On one occasion nine men of a detail of twelve were left dead where they had fallen.”

Hope, he said, was a key to survival, though it was severely shaken by the fall of Corregidor in May 1942, which secured overall victory for the Japanese in the Philippines and resulted in the influx of thousands more prisoners, including MacArthur’s successor, General Wainwright.

Almost a year later, on April 4, 1943, having survived bouts of scurvy, jaundice and dengue fever and covered in sores, an emaciated Dyess escaped Davao with nine American PoWs and two Filipino convicts, all carefully chosen for the skills they possessed.

Travelling at times at less than 100 metres an hour, they slogged and slashed their way through jungle, swamp, mountains, swollen rivers, stifling heat and pouring rain. They had planned and prepared the escape for months.

They battled illness, tropical ulcers and infection, leeches, sword grass and a swarm of giant bees. They prayed and pressed on through it all, always casting an anxious eye behind. Their captors never caught up with them.

Eventually, they reached their objective, which Dyess doesn’t identify by name, calling it only “a fly-bitten place” with little food. They rested until orders came and, as Dyess put it, they “were fighting men once more.”

Three months later, Dyess and two of the Americans who escaped with him boarded the U.S. Navy submarine Trout and went to Australia, where they related their experiences to MacArthur. They had pulled off the only large-scale escape of Allied PoWs from the Japanese in the Pacific Theatre during the Second World War.

It was the first any outsiders heard of the death march or the conditions inside the PoW camps. The general wanted their story told to the world to expose the Japanese atrocities. But the U.S. government, fearing American and other Allied prisoners would pay the price, said no.

MacArthur attributed the censorship to the possible consequences for the Europe-first policy adopted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration, who feared that the American public would shift its focus west and demand retribution against Japan at the expense of the European campaign.

“Whatever the cause,” mused MacArthur, “here was the sinister beginning of the ‘managed news’ concept by those in power.” He called it an affront to freedom of expression and a violation of human rights.

In fact, the Chicago Tribune’s version of Dyess’s story began its release just over a month after he died, running in serial form for several weeks. It was picked up by more than 100 American newspapers. The writer, Charles Leavelle, called it the biggest story since Pearl Harbor. Dyess’s book was released in 1944.

The news reverberated throughout the Allied world, including Canada.

Some 1,685 Canadian soldiers had been taken prisoner after Hong Kong fell on Christmas Day 1941. They would languish under horrific conditions for four years; just over 1,400 made it home. Their suffering would haunt them for decades.

Advertisement