In the Battle of Frezenberg, the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry would give no ground

The PPCLI had been the brainchild of Hamilton Gault, a wealthy Montrealer who offered $100,000 to equip and train a battalion comprised of veterans of the British Army who had moved to Canada. Captain Gault, a veteran of the Boer War, was promoted to major and served as second in command to a professional British officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Farquhar.

When they arrived in England, the PPCLI were attached to the 27th British Infantry Division, one of three divisions formed by recalling battalions from various outposts of the Empire. The PPCLI’s “old originals” were a good fit for a division composed of professional soldiers, but apart from Major-General Thomas Snow and his Brigadiers, who had fought in the 1914 campaign, few had any experience of the kind of war that was developing on the Western Front. Snow, who was recovering from a serious injury when his horse fell and rolled over him, was a difficult and stubborn commander who functioned as little more than a conduit for orders from above.

There was no time for combined-arms or brigade-level training before the division was rushed to France in December 1914. The PPCLI, ready or not, entered the trenches near Ypres early in January 1915. The trenches were “ditches dug across a sea of mud, too wide for protection from shellfire and too shallow to be bulletproof,” as Jeffrey Williams described them in his biography of Gault, First in the Field. When the PPCLI rotated out three days later, “swollen feet, dysentery and severe colds,” not wounds, were the chief troubles.

The regiment next moved a few miles north to take over trenches at St. Eloi, site of the infamous 1916 Battle of St. Eloi Craters. This was where Farquhar, who was proving to be a superb commanding officer, organized a sniper section to counter the enemy’s use of this tactic. Unwilling to stand on the defensive, he ordered the first large-scale trench raid of the war.

Farquhar called it a “reconnaissance-in-force,” and at 5:15 a.m. on Feb. 27, 100 men of No. 4 Company set out to do some damage to an enemy that the War Diary noted “had become very aggressive.” They crossed no man’s land without rousing the enemy. “Lieut. Crabbe then led the company down the trench whilst Lieut. Papineau ran down the outside of the parapet throwing bombs at the enemy.” During the withdrawal, Gault was wounded while assisting the stretcher-bearers and was evacuated to England.

During their weeks of misery in the line, 85 Patricias, including Farquhar, were killed, and losses due to wounds, sickness and shell shock further reduced their numbers. As David Bercuson notes in his history of the PPCLI, “some 300 of the men who stood on the parade square at Lansdowne Park…that previous August were permanently or temporarily gone. And yet the PPCLI had not yet seen a general action.”

Like the other battalions in the salient, the PPCLI was the victim of uncertain and indecisive leadership. Sir John French, the British Commander-in-Chief, was under orders to co-operate with the French army—but co-operation does not require capitulation to unreasonable demands. By day three of the battle, he knew that counterattacks against an enemy with vast superiority in all forms of artillery were a waste of precious lives. Withdrawal to a new defensive line was urgently required, along with reinforcements and all available heavy artillery.

French’s counterpart, General Ferdinand Foch, flatly refused to consider any changes that would draw resources away from the offensive designed to capture Vimy Ridge or the complementary British offensive at Aubers scheduled for May 9. Against all evidence, Foch claimed that French troops, who had been pushed back across the Ypres Canal in the first gas attacks, were committed to recovering all of the ground they had lost. The British, he insisted, must not only stay in the exposed salient, but also join in when the French army advanced.

Foch used this argument to persuade French that operations such as the costly advance of the Indian Army’s Lahore Division, in support of an unsuccessful French attack, must continue. When Lieutenant-General Horace Smith-Dorrien—the general who, many believed, saved the original British Expeditionary Force at Le Cateau in 1914—urged an end to such attacks and preparations for withdrawal, French dismissed him as too pessimistic.

As losses mounted and the French Army withdrew artillery from their sector, French finally ordered a withdrawal to begin the night of May 3-4. The new line, apparently selected from a map without reference to the ground, offered little protection against the overwhelming firepower that the enemy could bring to bear.

The PPCLI and its sister battalions in the British Army’s 80th Brigade had waited out the first phase of the German offensive on the southern side of the salient. Its War Diary reports that the battalion “remained in trenches without relief owing to the battle being fought to the north.” They stayed there for 10 days, suffering losses of 8 killed and 66 wounded, until ordered to withdraw.

The Patricias occupied a sector of the new line in front of Bellewaerde Lake, working all night to build fire trenches to add depth to the position. Of necessity, these trenches were located on a forward slope, open to direct observation from the high ground to the east. The British Official History describes the trenches of the new line as “narrow and only three feet deep—they were difficult to improve as some even with slight evacuation reached water level. The soil was treacherous; the trenches fell in even without bombardment and there was a great lack of sandbags to repair them.… The position, though defensible, was a framework on which much was still required to be done. Without deep dugouts to shelter the men during bombardment, it does not seem probable that any troops could have held out for long.”

On May 4, the PPCLI War Diary read: “Bellewaerde Lake. Men worked all night on new trenches but by 7 a.m. the Germans were noticed advancing over the crest of the ridge to our right and by 9 a.m. enemy artillery began shelling the trenches and this heavy shelling continued throughout the day, trenches in many places were blown in…26 men killed, 96 wounded, two of which died two days later.”

After a 24-hour respite in reserve, the PPCLI returned to the front. The Germans were now confident that they could win control of the remainder of the salient, attacking all across the front. On the morning of May 8, after “a bombardment more violent than anything the Regiment had seen before,” the German infantry attacked. The first wave was met by rapid rifle fire, checking the advance, but both the Patricias and the King’s Royal Rifle Corps on their right flank were taking casualties.

Gault, who had returned to the regiment with a draft of 47 reinforcements straight from England, assumed command after Lieutenant-Colonel H.C. Buller was wounded. Gault ordered everyone available—“Signalers, Pioneers, Orderlies and Servants into the support trenches”—to prepare to fight to the last man. The shelling began again and Gault was among the severely wounded. Command passed to Captain Agar Adamson, and when he was wounded, it passed to Lieutenant Hugh Niven, the

senior surviving lieutenant.

The Patricias would not give ground, even after the battalion on their left flank was overrun. The War Diary notes the arrival of a platoon from the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry, bringing small arms ammunition and reinforcements. “Another attempt by Germans to advance was stopped by our rifle fire, although some reached the fire trench on the right.… None of our men there were alive at this point.”

At 11:30 a.m., the PPCLI was relieved, handing over its support trenches to a reserve battalion “who gave us assistance to bury our dead.… It was impossible and imprudent to attempt to reach the fire trenches” where most of the dead lay. For the Patricias, the battle, designated “Frezenberg Ridge,” was over. They had lost 10 officers and 375 other ranks, including 95 killed in action and 81 missing, presumed dead.

The opening of the French Army’s Artois offensive and First British Army’s attack on Aubers Ridge brought no relief to the battered battalions in the salient. What was left of the British Divisions fought on for another week before exhaustion and ammunition shortages forced the Germans to pause. Ten days later, with a favourable wind, clouds of chlorine gas rising to 40 feet drifted toward the British lines, forcing a further withdrawal. The new line held long enough to persuade the enemy to pause again and consolidate—this time the battle known as Second Ypres was over.

Frezenberg became a treasured battle honour for the Patricias, who held out against great odds. But after the battle, their role as a detached battalion in the British Army could not be maintained. A plan to keep the regiment’s elite status by reinforcing them with companies from McGill and other Canadian universities was implemented, but when 27th Division left France for the Mediterranean, the PPCLI were attached to Brigadier-General Archibald Cameron MacDonell’s 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 3rd Canadian Division. Under his command they would return to the salient to take part in the battle of Sanctuary Wood in June 1916, before making the journey to the Somme. Their war was not yet half over.

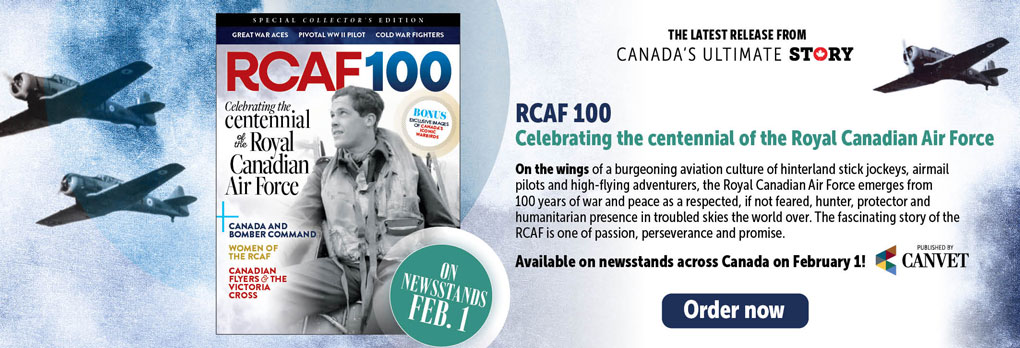

Advertisement