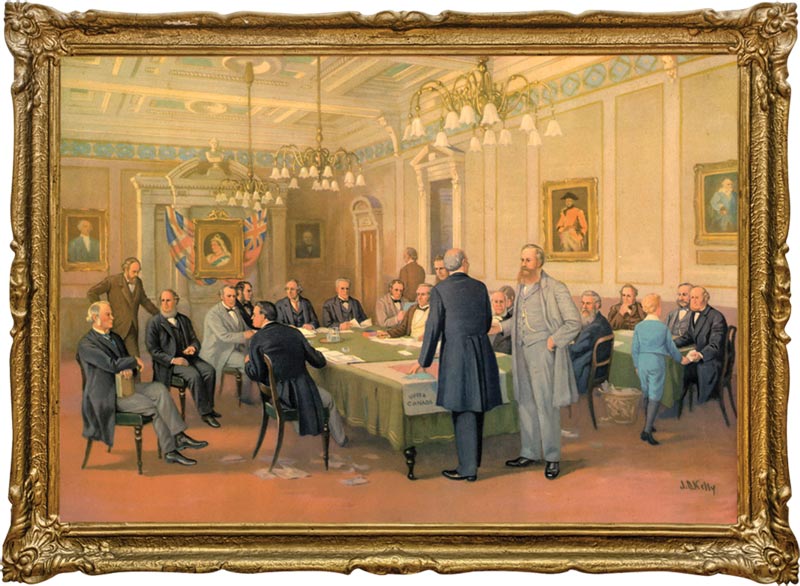

In 1866, the Fathers of Confederation—among them John A. Macdonald, George-Étienne Cartier, Alexander Galt and George Brown—were in London, staying at the Westminster Palace Hotel.

They were fine-tuning the British North America Act which, when passed, would create the Dominion of Canada. At a different hotel was Joseph Howe, who was trying to get Nova Scotia out of Confederation, waving a petition with 30,000 signatures.

“Macdonald was the ruling genius and spokesman,” according to Sir Frederic Rogers, the Permanent Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies. But there were a few non-genius moments.

Macdonald woke up in the middle of the night to find that both he and his bed were on fire. His hair and hands were singed and his shoulder was burned—but he carried on.

The road to Confederation had been paved with mistrust, hostilities and alcohol. The Fathers of Confederation were an unlikely group, divided along political, religious and linguistic lines.

There were weeks of negotiating, creating, debating and drinking.

George Brown described Cartier as “that damnable little French Canadian” and Macdonald as a drunken corruptionist. Macdonald responded that the voters “would rather have a drunken John A. Macdonald than a sober George Brown.” They eventually got both.

Along with the Irish Catholic Thomas D’Arcy McGee (both qualities counting against him, in Brown’s view) and others, they had to convince the colonies to unite. One of their arguments was they needed to protect themselves against the already imperial-minded Americans. Added to that threat was the fact that the British government wanted to reduce its spending in the colonies, particularly on defence.

In Charlottetown and Quebec City, this group made eloquent pleas for their federal dream to delegates from the colonies. There were weeks of negotiating, creating, debating and drinking.

The document they crafted promised peace, order and good government and was adopted by delegates to the Quebec conference in 1864, with the exception of Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. The delegates then had to return to their own people and sell the idea. The Fenian invasion in 1866 helped cement the idea that the colonies needed to unite.

The bill was held up for months in the British parliament and finally signed by Queen Victoria on March 29, 1867. On July 1, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and the Province of Canada were proclaimed the Dominion of Canada.

A cannon was fired on the Plains of Abraham to celebrate Confederation. In Ottawa, the military assembled on Parliament Hill to fire a salute. They neglected to take the ramrods out of their rifles though, which sailed over Sparks Street. In Toronto, they roasted an ox in front of St. Lawrence Hall.

Confederation had been a bruising process that left many unhappy. McGee, considered one of the country’s greatest orators, addressed Parliament. “What we need above all else is the healing influence of time,” he said. A few hours later, he was dead from an assassin’s bullet. The great Canadian experiment was underway.

—

Find many more stories in our O Canada special issues, NOW available in our SHOP!

Advertisement