On Remembrance Day or, for a naval veteran, Battle of the Atlantic Sunday in May, I am called upon to recall those fellow Canadians who gave their lives for us. At naval events the ships that were lost are frequently read out, but I have this vaguely detached feeling. I was never in a ship that was torpedoed, or even at risk, as far as I know. Nor did I serve in a ship and get to know her and her idiosyncrasies—one I could call “my ship”—that was subsequently lost. Assuredly, I appreciate the price paid, in lives, in ships, in aircraft, during the struggles. After all, we were in the same service, faced potentially the same dangers. But to some extent it’s a bit distant. It doesn’t affect me on a personal level, in my heart or gut. And this is probably true enough for many Canadians unless a family member was lost.

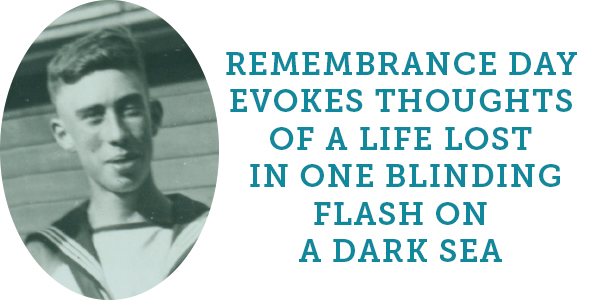

Then I remember one person, a young man about five years older than myself, with whom I spent a quiet but memorable afternoon 62 years ago. Nine months later he lost his life in the sinking of His Majesty’s Canadian Ship Shawinigan. Sub-Lieutenant Donald French was with me on board the armed yacht HMCS Vison. That’s who I remember on these occasions.

In February 1944, Vison was at sea in the Bay of Fundy with a class of anti-submarine students, hunting a tame loaned-in Dutch submarine as part of their training. While it was cold, just above freezing, it was a lovely, clear, mostly calm afternoon. The drill was that the sub would submerge, then alter course. The class on the asdic equipment was in a small hut on top of the ship’s bridge, with concealing curtains drawn around its windows (not portholes! This was an ex-civilian 135-foot motor yacht!). They would try and locate the sub and set up a theoretical attack. The sub towed a “buff,” a small buoy, so we didn’t run into her. The exercise was without any kind of danger.

I was an ordinary seaman helmsman, about to turn 19. Don French, the officer of the watch, was 24. In a small ship like Vison we were alone on the bridge. The trainees above us simply passed orders for courses and speed down a voicepipe to the officer of the watch and he directed me what to do. Being both Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve members, and both from Ontario—Don from London, me from Toronto—and with similar civilian upbringing and schools, we chatted casually about our lives as we went about our uncomplicated tasks. No big deal, not memorable at the time. Just two sailors enjoying the pleasant afternoon. But in retrospect, a fond memory.

A few months later, Don, now an acting lieutenant, was appointed to the corvette Shawinigan of the Western Local Escort Force, patrolling and on convoy escort around Cape Breton. I went for a commission and after a brief familiarization month in the Reserve Division in Charlottetown began my sub’s courses. Then in November 1944, we were all shocked to hear Shawinigan had been torpedoed while travelling between Sydney, N.S., and Port aux Basques, N.L. There were no survivors. The U-boat—U-1228—had been sent into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, but was having snorkel problems that her commanding officer was unable to repair. Without it in those restricted waters, he resolved to return to Germany for repairs, and on the dark night by sheer chance encountered Shawinigan heading back to Sydney alone. He sank the corvette with a single acoustic torpedo. All 91 aboard were lost, before even the briefest message could be sent.

Then, and since, I remember that quiet, pleasant afternoon I spent with Don French in the small wheelhouse of Vison. Now he’d have no future, no return to the University of Western Ontario, no marriage to his fiancée Marion back in London. No life at all. His parents, William and Lily French, desolated at the loss of their son, with only his sister Frances left to them. I went on to serve for 32 years in the reserves, had jobs, a family, homes. But Don’s whole future, whatever it could have been, was lost in one blinding flash during a dark night at sea.

And that is what I remember. Not a distant thought of people I never knew, ships in which I’d never served. But a nice guy with whom I spent but an afternoon all those years ago.

Advertisement