![CoppLead A dramatic photo of the battlefield along the Caen-Falaise road, August 1944. [PHOTO: LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—E010858649]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/CoppLead.jpg)

In July 1944, the German Army concentrated more panzer divisions in the open fields south of Caen than in any other sector on the eastern or western front. Relying on infantry and artillery to meet the Soviet Union’s summer offensive and to check the Americans in the dense Bocage country in Normandy was a gamble, but Hitler and his senior officers knew a breakout in the Anglo-Canadian sector would open routes to Falaise and the River Seine while cutting off most of the German forces in Normandy. The Caen-Falaise plain was such good tank country that it could only be defended by the best panzer divisions.

The Soviet offensive on the eastern front had begun on June 22 and by mid-July the Germans were in full retreat. On July 25 the much-delayed American operation, code-named Cobra, began. Within three days it was clear the American breakthrough had become a breakout and German Field Marshal Günther von Kluge, with Hitler’s permission, began shifting panzer divisions to meet the Americans.

When General Bernard Montgomery learned about the American advance and the activation of General George S. Patton’s 3rd United States Army, he decided on a course of action that had profound consequences for the rest of the Normandy Campaign. General Richard O’Connor was ordered to cancel preparations to employ his three British armoured divisions in an attack down the Falaise road. Instead, Montgomery moved O’Connor’s powerful 8th Corps west to support the American advance.

Montgomery was convinced the Germans would regroup and organize a new defensive line by moving back to the Orne River. His directive of July 27 declared “that anything we do elsewhere must have the underlying objective of furthering the operations of the American forces to the west of St. Lô and thus speeding up the capture of the whole of the Cherbourg and Brittany peninsulas; it is ports that we require and quickly.”

The British advance would allow Patton to concentrate on the liberation of Brittany, where Allied planners proposed to build a port capable of supplying the Allied armies for what everyone assumed would be a prolonged struggle to liberate Paris and advance into northern France.

With O’Connor’s advance, codenamed Operation Bluecoat, set to begin “at the earliest possible moment,” the left wing of 2nd British Army and all of 1st Canadian Army were to press attacks “to the greatest degree possible with the resources available.” The enemy must, Montgomery insisted, “be worried and shot up and attacked and raided, whenever and wherever possible,” so that ground could be gained and the Germans prevented “from transferring forces across to the western flank to oppose the American advance.”

The July 27 directive, however, was a major strategic blunder, perhaps the worst of Montgomery’s career. It does not require hindsight or foreknowledge of Hitler’s decision to stage a major counterattack at Mortain to recognize that Montgomery was shifting resources away from the decisive ground south of Caen at precisely the moment the enemy was thinning out his defences.

Montgomery’s failure to anticipate the German reaction to Cobra was only the beginning of the problems his actions created. The ground south of Caumont, where Bluecoat was to take place, consisted of some of the worst Bocage country, plus a series of ridges, including Mont Pinçon; the highest point in Normandy. Beyond Mont Pinçon the terrain was so hilly and wooded that it is known as la Suisse Normande. There were few roads and fewer still going in the right direction. All of this was well known to staff officers in both the British and German armies, which is why the Caumont front had been inactive since early June.

As the final preparations for Bluecoat were underway, Montgomery met with General Harry Crerar to explain his intentions and urge the Canadian army commander to maintain the pressure in the Caen area. Crerar promptly required Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds “to draw up plans for an attack, axis Caen-Falaise, objective Falaise,” to be carried out in great strength with maximum air support. Crerar thought such an attack would be ordered if Bluecoat proved successful—that is, if the British forced the Germans to withdraw on the Caen front. The day after Bluecoat began, July 31, Hitler presided at a conference to consider a strategy for the western front. He still believed a second Allied landing in the Pas de Calais was possible but the deteriorating situation for his forces in Normandy demanded action. The possibility of a staged withdrawal to the River Seine was dismissed as the river line could not be held with available troops. Hitler ordered the construction of a new defensive line further east, based along the River Somme. However, he insisted his front-line commanders still concentrate on stopping the Allied breakout. Four divisions, including two from 15th Army, were on their way to Normandy but more would be needed if a new front was to be established.

By Aug. 1 there were four panzer divisions on the American front, three facing the British and just two immediately east of the Orne. This situation cried out for a major attack in the Caen sector to cut off the Germans. However, Montgomery and Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower were still obsessed with Brittany. Fortunately for the Allies, Hitler intervened by ordering Kluge to cut off Patton’s 3rd Army at Avranches.

Montgomery’s concept of future operations began to change Aug. 4 when he issued a new directive which placed less emphasis on Brittany. “The enemy front,” he declared, “is now in such a state that it could be made to disintegrate completely.” First Canadian Army was ordered to help “force the enemy back across the Seine” by a carefully staged advance towards the town of Falaise.

When Simonds began to study the problems of mounting such an operation, the lessons learned in Operation Spring (Legion Magazine, May/June 2012) were clearly on his mind. His first “Appreciation” outlined new ideas for overcoming enemy defences. “The ground is ideally suited to the full exploitation by the enemy of the characteristics of his weapons. It is open, giving little cover to either infantry or tanks and the long range of his anti-tank guns and mortars, firing from carefully concealed positions, provides a very strong defence in depth. This defence will be most handicapped in bad visibility, smoke, fog or darkness, when the advantage of long range is minimized.”

Simonds decided on a night attack, as in Operation Spring, but this time he planned to use heavy bombers to neutralize the enemy defences and armour to get beyond the enemy gun screen. The tanks were to be accompanied by infantry riding in armoured personnel carriers improvised by removing the guns from the self-propelled, M7 field artillery vehicles that 3rd Division was trading in for towed 25-pounder field guns.

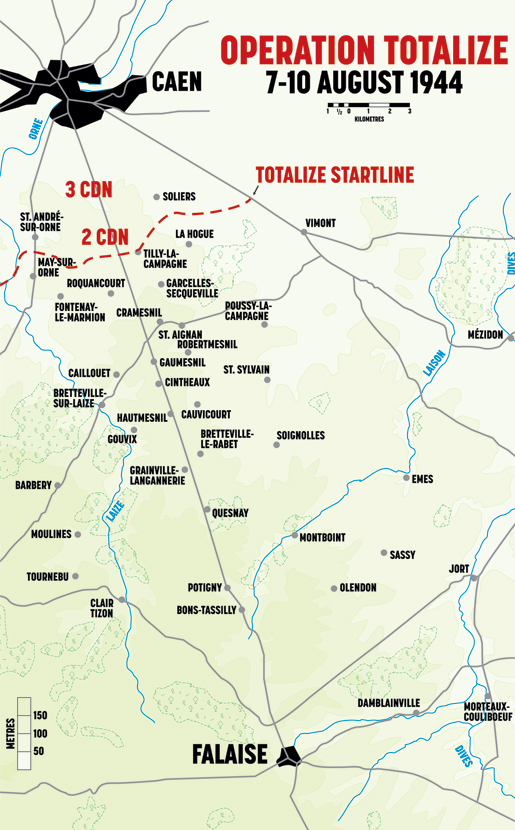

The final plans for what was codenamed Operation Totalize required the two available infantry divisions, 2nd Canadian and 51st Highland, to break through the first line of German defences during the night with 4th Canadian and 1st Polish Armoured divisions moving up to take over an advance “towards Falaise.” Both infantry divisions were in rough shape, as was 3rd Canadian which had been pulled out of action after the senior medical officer had warned that “after seven weeks of continuous over-the-top type fighting” the men needed a rest to survive. The 51st Highland Div. was a British Territorial Army division that—along with the rest of 1st British Corps—became part of the newly-activated First Canadian Army. The division, which had been sharply criticized by Montgomery for its performance in the fighting for the Orne bridgehead, had a new commander in Major-General Tom Rennie. However, nothing had been done to provide reinforcements for the depleted infantry. Meanwhile, 2nd Canadian Div. had suffered more than 2,000 casualties in July and received only a trickle of replacements. By Aug. 8 it was still more than a thousand men short.

The challenges confronting the infantry battalions paled in comparison to those facing the armoured regiments that were to lead the breakthrough in Totalize. On Aug. 2, the results of a detailed study of Allied armour were released. Investigators from England were aware of the general criticism of Allied tanks being aired in the press and the British House of Commons, but they were surprised by the depth of feeling encountered in Normandy. All the units visited complained that the Sherman is outgunned and out-armoured by the Germans. To achieve some protection the regiments used the rest period to attach lengths of track over the front, back and sides of the tank. The technical team agreed that “this does not provide armour protection as we normally understand it, but when the track is lightly attached” it served to deflect enemy shot and might function as “spaced armour.” The Sherbrooke Fusiliers had experimented with every available type of extra armour and reported that Major Radley-Walters’ Sherman, covered in tank tracks, had survived two hits while accounting for 12 enemy armoured vehicles.

![CoppInset2 A member of the Provost Corps searches a German prisoner near Tilly-la-Campagne, August 1944. [PHOTO: HAROLD G. AIKMAN, LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA—PA162000]](https://legionmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/CoppInset2.jpg)

Meanwhile, little could be done to make the Sherman 75-mm gun an effective anti-tank weapon. The only real hope appeared to be the 17-pounder, though tank crews noted the flash from the gun made observation at ranges of less than a thousand yards very difficult, and the high-explosive shell was ineffective. Some units saw two 17-pounder Shermans per troop as the best compromise, but there were not enough available to maintain the current ratio of one-in-four. The armoured regiments would have to make do with what they had.

A strange quiet descended on the night of Aug. 7. While a waning full moon loomed large and red in the eastern sky, a ground mist carpeted the flat countryside. Shortly before 11 p.m. the drone of aircraft could be heard and then the first wave of heavy bombers was overhead. Red smoke shells fired by the artillery identified targets and flares dropped by the master bombers marked the aiming points. A full-scale artillery barrage began and the lead troops of the British and Canadian battle groups advanced.

The enemy forces south of Caen consisted of a newly arrived, full-strength, infantry division: the 89th, the 272nd (veterans of the July battle), the armoured battle groups of the 12th SS, a Tiger tank battalion, and the 88-mm guns of the Luftwaffe Flak Corps. A second full-strength infantry division was crossing the Seine and would reach the area north of Falaise in less than a week. The Polish Armd. Div. was fully deployed a few days before Totalize, so on paper, 2nd Canadian Corps had three infantry, and two armoured divisions and two armoured brigades, outnumbering the enemy by a margin of three-to-one; the minimum military theorists thought was needed when attacking a well-organized opponent.

The 89th Div. had been briefed to expect a major offensive but the timing, weight and character of the initial attack caught them by surprise partly because bombs fell well to the north of their forward defence lines. It is not clear why the 641 Lancasters and Halifaxes bombed so inaccurately that night, especially since the artillery marked the prominent targets. Presumably the coloured smoke drifted in the light breeze misleading the master bombers. Concentrations around mean points of impact were excellent but only one of the four main targets, the village of La Hogue, was squarely hit.

The story of Operation Totalize will continue in the January/February 2013 issue.

Email the writer at: writer@legionmagazine.com

Email a letter to the editor at: letters@legionmagazine.com

Advertisement