by Ray Dick

|

The struggles of the Canadian military to provide an effective fighting force to cope with an increasing workload of domestic responsibility and international commitments despite years of budget cuts and manpower loss have become well known both at home and abroad. What is less well known is the plight of the country’s citizen soldiers–the land force reserves, or militia, with its proud traditions and regimental ties that date back in some cases to before Canada was a country.

With 133 units scattered through 125 cities and towns across the country, the militia–the army component of the 27,500-strong reserves–was suffering along with its regular force brothers from the same problems of bad morale, loss of manpower, lack of and deteriorating equipment and especially lack of financing. While naval and air reserves integrated relatively well with the regular forces in manning coastal patrol vessels and air transport, it was a different story for the militia that had sunk in manpower to roughly 11,000 a few years ago from a peak of approximately 46,000 after World War II.

And the present, 15,300 militia personnel are being called upon to provide increasing relief to the regular forces, which are hard-pressed to provide adequate manpower to meet an increasing number of international peacekeeping and peace-making commitments. At present, roughly 20 per cent of the peacekeeping forces in such places as Bosnia is supplied by the militia.

It was a deteriorating situation that could not be ignored. In 1995 the government saw the writing on the wall and appointed the late chief justice Brian Dickson, York University professor Jack Granatstein and retired lieutenant-general, Charles Belzile to a Special Commission on Reserve Restructure to begin the process of rebuilding the militia. What they started has turned into a continuing program at National Defence–the Land Force Reserve Restructure, LFRR–that falls under the watchful eye of former House Speaker John Fraser and his minister of national defence monitoring committee.

In a policy statement issued in 2000 on LFRR, the government stressed that the army reserve is a vital component of the country’s military capability. There was one Canadian Army based on two components–regular and reserve–each of which was essential to providing Canada with strategic defence capabilities. “Located in communities throughout Canada, the army reserves exist primarily to provide the framework for expansion should the need arise. This is the raison d’être of our reserve force, which is characterized by its role as a ‘footprint’ in communities across the country. Its significant social role of fostering the values or citizenship and public service is one which, as Canadians, we have come to cherish and must protect.”

The statement adds that reservists also help to augment the regular forces, which have been hard-pressed to meet an increasing number of commitments abroad. “Since the end of the Cold War our reliance on these augmentees has increased due to the high tempo of our operational activity. We aim now to have reservists provide up to 20 per cent of the personnel of these deployments. The army reserves are even more prominent in our defence against natural disasters and local emergencies, such as the Saguenay and Red River floods and the ice storm of 1998…. We need them more now than at any time since WW II.”

The government statement said militia numbers would be increased to at least 18,500 by 2006, a senior official would be appointed to manage LFRR and that the Fraser committee would monitor the program.

That senior official appointed to oversee the LFRR was Major-General Ed Fitch, former commander of land forces in the western area and assistant chief of land staff to Lt.-Gen. Mike Jeffrey. He said he is tackling the LFRR program along two lines of advance. The first part of the plan is to increase recruitment and to build a consensus among reservists, regular army and interest groups on the role of the militia. The second part would include mobilizing the resources to pay for the program. He was “very satisfied” with the progress on consensus for the plan, or phase one. As for where the resources would come from, “that is less clear.”

Attracting new recruits for the reserves was slow to start, said Fitch, but “recruits are now flowing in “and there should be no problem in meeting the target of 15,500 by the end of March next year. “In some areas, such as in Ontario and the Atlantic region, they are coming in faster than we can accept them. We just can’t pay them all.” He attributes the increased interest, among students especially, to work that has already progressed in restructuring, such as improved pay and working conditions. “The militia needs to be competitive in employment,” he said. “It’s a part-time job and we’re competing against fast food companies such as McDonald’s and A&W.”

“In the militia the recruits get adventure and leadership training,” said Fitch. “You don’t get that from flipping burgers.”

It is a restructuring of a militia that can trace its history back to the early days of French colonialism, when militia forces aided French regulars in Quebec in keeping the English and the Iroquois at bay, and to the citizen soldiers who fought alongside English regulars in the War of 1812. A young Canada did not get a regular army, small as it was, until 1873. It is a restructuring that Fitch says was long overdue. The last major reserve restructuring was in 1964 which was essentially cleaning up business from WW II. Fitch said a lot of things have changed since then. “Something had to be done.”

Those changes started in the early 1960s as successive governments with an eye to fiscal restraint in the Cold War era either froze or cut back on defence spending. What the country ended up with was an over-worked military with obsolete equipment and ever-shrinking numbers. At the same time, governments were frequently dispatching troops on peacekeeping, peace-making or combat duty and the military regulars had to turn more and more to the reserves, which were also shrinking, to fill their ranks.

And the problems were mounting for the militia, writes historian Jack Granatstein in the latest issue of the Canadian Military Journal: “Recruits took months to be processed, and retention was poor as students joined, trained for a few months and then left. Enrolment seemingly rose and fell in step with the fluctuating level of employment. Annoyingly, the pay system didn’t work. Because units were so under strength, the level of training too often verged on the rudimentary. Most effort was devoted to endless cycles of new recruits undergoing individual training. Equipment in units was either old or lacking and, although new militia training support centres had been or were being built with good training areas and innovative ways to share equipment, the equally strapped regulars sometimes had to take armoured vehicles away from the training centres for deployments abroad.”

And there were other problems for the militia, including the issue of regimental pride. Because some of the reserves in rural areas were so small in number they could only augment the regular forces on an individual basis, suggestions were made that they should be consolidated into larger units where they would tend to lose their regimental identities. This was a non-starter for the militia, many of whom joined the units because they served with that particular regiment during their active service, or their fathers or other relatives did. What Fitch found during his investigations was that most units are in locations where they were 50 years ago. While growth in urban areas has been enormous, it was not so in rural areas.

“We have found that the number of units is about right,” said Fitch. What the Defence Department was trying to do with its current successful recruitment drive is to add depth to the fighting units so they will not have to throw away their regimental battle honours and will be able to contribute as at least sub-units in future peacekeeping or armed conflicts. An example Fitch gives is that a complete reserve rifle company, about 130 personnel, has taken its place in regular troop rotations to Bosnia.

Another problem the militia has faced is in job guarantees from private sector employers to reservists called to duty with the regular forces–a benefit guaranteed to reservists in the U.S. “What we have come up with is a Canadian compromise, said Fitch. A bill now is before Parliament that would provide job guarantees, but only in cases of emergency call-up of reserves. He said a blanket guarantee of job protection as in the U.S. is a double-edged sword. Some employers would hesitate to hire reservists under those conditions.

The pace of progress on LFRR has caught the eye of the country’s top general, Chief of Defence Staff Ray Hénault. “I am heartened by the progress made recently in the LFRR project, particularly as the process has been a long, and at times, difficult and contentious one…. We are meeting our recruiting goals, improving the current capabilities of the reserves and adding new capabilities to focus the reserves on new and important operational roles.

“But I have also said that difficult choices need to be made, and it will fall to everyone in uniform to make the necessary choices that will ensure the institution evolves into the most effective fighting force possible to meet today’s threats.”

And the Fraser committee in a report issued this year agreed that progress has been made in the first phase of LFRR, to be completed by March next year, which it describes as a period of stabilization and assessment in which the chronic problems of the army reserves–recruiting, retention, enrolment, equipment and funding–are addressed. This sets the stage for the second phase, and for restructuring decisions designed to meet the country’s defence requirements into the future. The committee’s progress report, however, expressed one major concern: “While recognizing progress made thus far, the committee is concerned that phase two of LFRR, and perhaps even phase one, demands resources not currently in the army budget. We do not yet know what phase two will cost.”

It is the financing part of the program, or phase two, that is also a primary concern for several military analysts and observers. Retired lieutenant-colonel John Selkirk, executive director of the militia lobby group Reserves 2000, puts the LFRR project in perspective: “The militia is not back to health, but with a total force now at about 15,500 it is better than it was.” He said further expansion is needed and that the government will have to come up with the money. Adding another 3,000 militia to the roster to meet the objective of 18,500 by 2006 would cost $147 million–“not much when you consider a budget of $12 billion for national defence.”

Selkirk said the reserves over the years have been treated as a neglected asset, getting short shrift and being treated as second best in military consideration. “The reserves were feeding off themselves, and they were down to skin and bones.” The biggest problem over the years was that the reserves were suffering from lack of purpose. An example of improved conditions, he said, is that there has been settlement on a role for the militia–one that will form a basis for mobilization in case of national emergencies, augment the regular force in times of need and–based widely in communities across the country–connect Canadians to their military.

Other military analysts believe lack of financial support from the federal government has brought the military, both the regular forces and the reserves, to near the breaking point as too few troops soldier on with outdated equipment and an increased workload. Most military lobby groups, including the Conference of Defence Associations, The Royal Canadian Legion and even the government’s own Standing Committee on National Defence and Veterans Affairs and the auditor general, say the military needs at least an extra $1 billion a year in its budget over the next five years.

Retired lieutenant-general Lou Cuppens, chairman of the Legion’s national defence committee, said “it’s all well and good” to have studies on what to do about fixing the reserves, but the “bottom line is that there is no money” forthcoming to fix the problems. “The reserves are neither well trained, well equipped nor well compensated,” he said. The dire problems of the military in general had to be recognized by the government and acted upon if we want to have “a nation capable of defending itself.”

Analyst Martin Shadwick of York University is also pessimistic about the general problem of lack of funding for the military in general. “As long as the regular army is walking a tight funding rope, it is difficult to see how we could carry through with phase two of the LFRR,” he said. And although he admitted there has been some progress made in restructuring the reserves, if the financial woes of the military continued, any progress could begin to slide backwards. What was needed was more money for national defence, a follow-through of support on progress already made. The reserves needed more manpower and better equipment to back up the regular army.

Analyst Joel Sokolsky of the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ont., said that although “financing is always a problem in Canadian defence policy,” there was a greater need now for a well-equipped and well-trained militia to back up the regular forces considering the pace of peacekeeping, peace-making and war-making commitments in which Canada is involved. The role of the reservists was also changing to some extent. The Americans, for instance, are looking for more experts in city management and other civilian-type tasks needed in peacekeeping-type situations. This can free up the younger troops for any actual fighting.

A stronger and better-equipped reserve was also needed to come to the aid of the civil power in cases of national emergencies. “If we had another ice storm, for instance, we might have to pull some troops out of Bosnia,” said Sokolsky.

He said the terrorist attacks that claimed thousands of lives in September 2001 gave some boost to military spending, although most of the funding went to the Canadian Security Intelligence Service and increased control at border points. “What we must do is maintain that momentum,” he said.

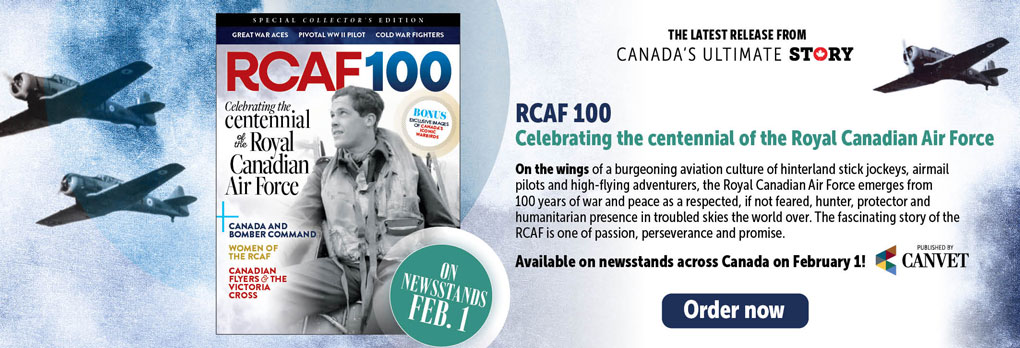

Advertisement