Theirs was a singular experience, the scale and intimacy of which were unique in the annals of conflict, even aviation, before or since.

The chivalric tradition among flyers began during the First World War. Known as Knights of the Air, they blazed trails in the skies in canvas-and-wood airplanes with rudimentary instrumentation, sans parachutes. They fought mano a mano, skill to skill, sometimes just metres apart.

It was, after all, the first war in which aircraft played a wide role—initially for reconnaissance and artillery spotting, then fighting and bombing.

As fighter squadrons were established and aerial conflict escalated, aces who scored five victories or more emerged. Personalities emerged with them, recognizable by the distinct aircraft and markings each of them flew: Richthofen in his red Fokker triplane; Bishop in his Nieuport 17; Rickenbacker with his “Hat-in-the-Ring” Nieuport 28.

Early crews of rival reconnaissance aircraft exchanged nothing more belligerent than smiles and waves. Eventually, they began tossing grenades and even grappling hooks at each other.

The first recorded incident in which an aircraft was brought down by another involved an Austrian reconnaissance plane rammed on Sept. 8, 1914, by Russian Pyotr Nesterov on the Eastern Front. Both aircrews were killed in the dual crash.

Battling freezing cold, buffeted by unpredictable winds and weather in flimsy, unreliable airframes, and increasingly threatened by their rivals’ incursions, pilots began firing handheld weapons at enemy aircraft, although they were rarely an effective means of attack.

On Oct. 5, 1914, French pilot Louis Quenault became the first aviator to unleash machine-gun fire on an enemy plane, propelling aviation into a new era. The dogfights escalated into desperate struggles over the mud-soaked trenches and wastelands of wartime Europe, the daily stakes as high as any could be.

“Now a dogfight is rather an exciting game actually,” pilot Thomas Isbell of 41 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps, told the Imperial War Museums. “You’d dive onto the first Hun you come across, you open out your guns…and no sooner you’ve got your guns on him, someone else has got their guns on you.”

At night, they would engage in the drunken, bittersweet celebrations and tributes to their fallen brethren, knowing all the while that horrible fiery death or disfigurement awaited them in the blink of an eye, a fraction of a second’s miscalculation, or a moment’s loss of concentration. Over time, the underlying stress would do its work, chipping away at their psyche.

In April 1917, the Royal Flying Corps’ worst month, the average life expectancy of a British pilot on the Western Front was 69 flying hours. Denied parachutes, many carried a handgun to avoid unnecessary suffering should their plane be burned or disabled.

Those who flew belonged to an exclusive club whose members quickly came to understand the special place they occupied. The rare air above 10,000 feet brought on hypoxia, a potentially fatal high, but there were no borders up there among the clouds.

In the Roberto de Haro novel Twist of Fate: Love, Intrigue and the Great War, the protagonist, a Louisiana Cajun named Quentin Norvell, describes the experience of flying in combat with the French Air Service during the First World War.

“There’s a bond between fighter pilots, even if we’re adversaries,” he says. “You see, we share the same things, the deafening noise of the engine which blots out our hearing, the speed and maneuverability of our planes, the sensation of flight, and the single purpose of defeating your opponent.

“It all comes down to one man pitted against another, high above the ground, making instant decisions that determine success or failure, and often death. There’s not enough time to think about hate.

“The enemy pilot knows my purpose is the same as his. If I hate anything…it’s the need for us to fight and kill each other.”

Indeed, opposing airmen went to astonishing lengths to help each other in the First World War, even warning the other side of where they were about to drop bombs and sending photographs of graves when they buried enemy dead.

Diaries kept by a young pilot from Pembrokeshire, England, reveal how camaraderie sometimes took precedence over hostilities, particularly between British and German flyers.

The notes taken by the 22-year-old Royal Naval Air Service pilot, William David Sambrook, suggest German adversaries warned their British enemies of where they planned to drop bombs.

Posted to Coudekerque airfield near Dunkirk, France, in 1916, Sambrook’s diaries tell of almost daily bombing raids on German-held aerodromes, docks, and Zeppelin sheds at Bruges and Zeebrugge in Belgium.

A few days later, with still no news of the missing man, another airman flew over the German airfield and dropped a message asking if they had information about the missing pilot’s fate. The British pilots received a prompt reply, also dropped from the air, confirming that the aircraft had been shot down over the sea.

“They said attempts had been made at rescue, but when the machine was brought in, the pilot was already dead,” Sambrook wrote. “He was buried with full military honours alongside two comrades at Marrakerke cemetery, Ostend. The message was accompanied by two photos of the funeral and the grave.

“There was also a message in German stating the name and place in German territory where our machines could land if they had engine trouble.” A war historian dismissed that as a shining example of German humour of the day.

Alan Wakefield, head of photographs at the Imperial War Museums, told The London Daily Mail in 2014 that such co-operation was far more common among pilots than among those fighting the war on the ground.

“I know of cases where German pilots dropped notes and photographs of a crashed aircraft and its occupant, saying they’d buried him and asking for his name so they could make a headstone,” he said.

“In one instance, a German pilot dropped a note saying he was about to bomb an airfield and suggesting that those on the ground should get out of the way.”

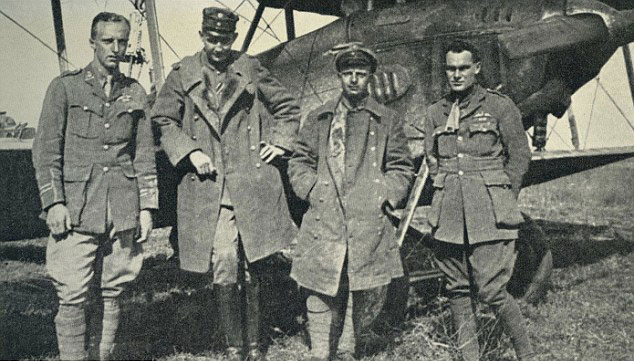

Captain Gerald Gibbs, a British pilot who was awarded three military crosses in six months, received adulatory fan mail from two German airmen whom he captured and then took to lunch. It was signed “with chummy German airman greetings.”

Gibbs earned the Military Cross after capturing the plane and its two-man crew by disabling its engine and forcing them to land behind British lines in Macedonia.

“I came quite close, watching the observer in case he aimed his gun in my direction, and was amazed to see he was fluttering a white handkerchief,” Gibbs wrote later.

“He landed in a pretty good field as I circled round. I then landed alongside, jumped out with my revolver. The observer threw up but the tough little egg of a pilot looked surly.

“You can imagine how excited we were to get a German aircraft down intact with two live prisoners. We gave them lunch in our mess and then handed them over rather sadly to their escort.”

In a letter penned shortly afterward in March 1918, the German observer, Lieutenant Robert Walther, said: “Dear Captain! My pilot and I ask you quite warmly, if you might have the kindness to send us a few autographed pictures. They shall be a reminder of the brave and quixotic adversary in aerial combat, as well as of the comradely picture of your battalion.

“With chummy German airman greetings, much luck, and thank you very much in advance.”

Gibbs described the note, which sold at auction in 2014 for more than $30,000, as “very nice.” It is not known whether he honoured the request, but he dropped a letter over German lines to inform the enemy the two airmen were safe.

Shot down twice, Gibbs was credited with 10 aerial victories during the Mesopotamia campaign in the Middle East. He once bombed a German aerodrome from 100 feet and strafed the hangars from 20.

Gibbs also served in the Second World War. He died in October 1992 at 96.

The Brit was Robert Wilson, a captain of 32 Squadron, RFC, who had beaten out the flames on his legs and arms after he was forced to crash-land his aircraft behind enemy lines.

Boelcke followed him down but, rather than hold him at gunpoint and send him away for interrogation, he shook Wilson’s hand, took him for coffee in the mess, and gave him a tour of his aerodrome. It was Boelcke’s 20th aerial victory.

“When he went down, his machine was wobbling badly,” the German wrote later. “But that, as he told me afterwards, was not his fault, because I had shot his elevator to pieces.

“It landed near Thiepval—it was burning when the pilot jumped out, and he beat his arms and legs about because he was on fire too.

“I fetched the Englishman I had forced to land—a certain Captain Wilson—from the prisoners clearing depot, took him to coffee in the mess and showed him our aerodrome, whereby I had a very interesting conversation with him.”

It was not Boelke’s first act of chivalry. Seven months earlier, he had flown over British lines and dropped a letter informing Allied troops that he had visited one of their missing airmen, who was alive and safe in hospital.

After the war, Wilson described his encounter with Boelcke as “the greatest memory of my life, even though it turned out badly for me.”

A photograph of their encounter emerged in a German pilot’s photo album a century later—one of the last taken of Boelcke before he was killed in a mid-air collision with another German aircraft a month after.

“Flying in the First World War was almost like a gentleman’s club no matter which side you were on,” said Matthew Tredwin, an auctioneer who sold the album in 2016. “An unspoken camaraderie existed between Allied and German pilots.

“A lot of these men were celebrities of their time because what they did had a certain romance about it, even though it was deadly.”

There were exceptions to be sure—later pilots, including American Second World War ace Richard (Bud) Peterson, were known to shoot parachuting enemy pilots—but the chivalric tradition continued, though somewhat more measured.

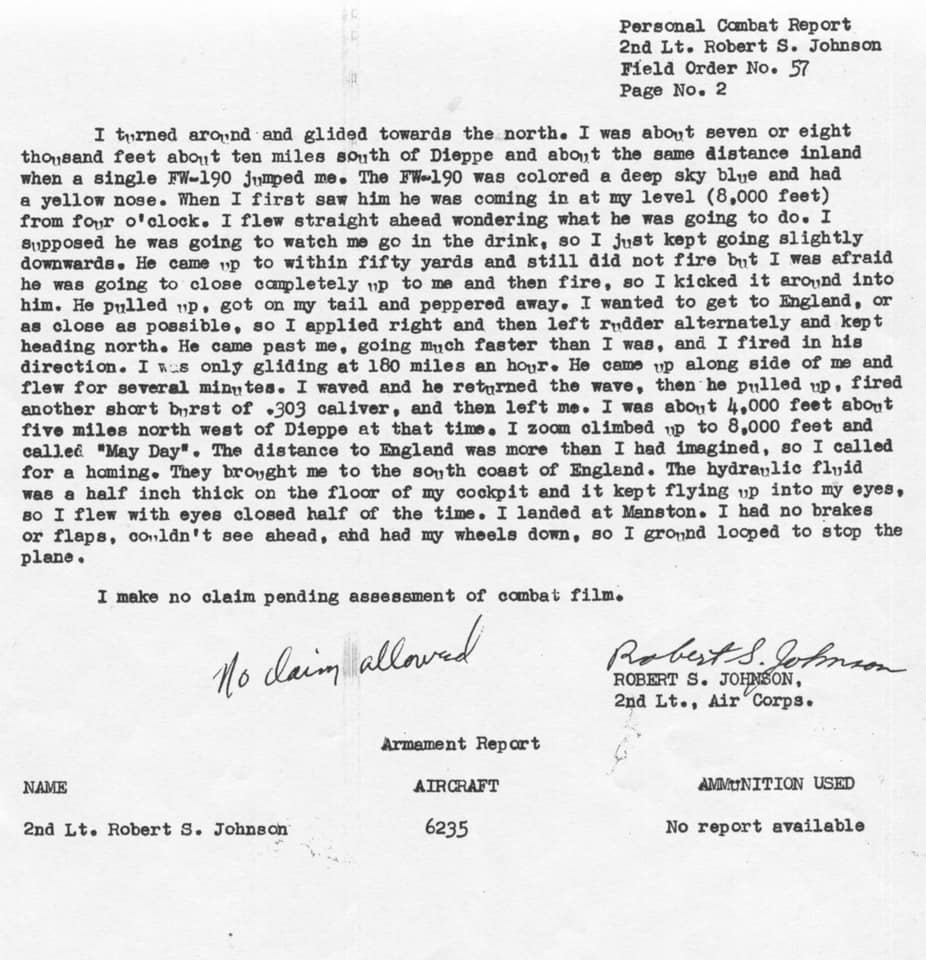

One day in June 1943, American pilot Robert S. Johnson’s P-47 Thunderbolt, a brute of an aircraft, had been repeatedly and severely raked by German gunfire. Johnson himself was wounded and, after making a miraculous recovery, was nursing his plane back to England with little hope of even making the English Channel.

Soon, however, a Focke-Wulf Fw-190 piloted by Luftwaffe ace Egon Mayer turned up and drew to within 45 metres before pumping machine-gun and cannon rounds into the helpless American until his superior speed caused him to fly past.

A frustrated Johnson fired but the German peeled away unscathed, only to pull up alongside him moments later. An incredulous Johnson watched as Mayer scanned the length of the Thunderbolt before shaking his head in astonishment that the thing was still in the air. The two made eye contact before the German peeled away, pulled up behind him once again, and poured more rounds into the helpless American aircraft. The Thunderbolt flew on.

Mayer pulled up alongside for the second time just as they reached the Channel. Home was just a few miles away.

Once again, Mayer assessed the Thunderbolt, shaking his head. Again, he waved at Johnson before peeling away. For a third time, the German settled in behind the P-47 and raked the American fighter, its airframe shuddering from the impacts.

Suddenly, the shooting stopped and Mayer swung alongside his rival a third time.

“Still shaking his head in wonder, the German observed the wreck of a P-47 Thunderbolt that was, in defiance of all logic, still flying,” said the Real History website.

“Seeing Johnson was watching him, the German rocked his wings in salute before peeling away. To Johnson’s eternal relief, this time Mayer was gone for good, heading back towards German airspace.”

Chivalry? Grudging respect? Maybe some. But, truth be told, the German had simply run out of ammunition.

Johnson landed safely, with more than 200 holes in his aircraft—including five in his propeller—along with burns and other wounds. He would return to duty five days later.

Mayer was killed in March 1944. He had shot down 102 Allied planes.

With the advent of jet aircraft, radar systems and heat-seeking missiles, air combat became less and less intimate after 1945. By the Vietnam War, pilots were shooting down enemy aircraft without ever actually seeing them on much more than an in-cockpit screen. Today, drones conduct air attacks flown by controllers in air-conditioned rooms hundreds and thousands of kilometres away from the action.

The chivalry of the skies is dead.

Advertisement