“A folk hero to some, a murderer to most, Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) terrorist Paul Rose is one of the most polarizing figures in Quebec history,” historian Éric Bédard told The Montreal Gazette.

Rose was born in the Montreal neighbourhood of St. Henri on Oct. 16, 1943, but spent much of his childhood in Ville Jacques-Cartier, an impoverished municipality in Longueuil that reportedly didn’t even have sewers. Rose’s early exposure to the working class most likely imbued his activism with the want to liberate Quebec’s “working man.” Throughout the 1960s, Rose participated in the waves of nationalist and French-language demonstrations throughout the province before finally make ripples of his own.

It was at Montreal’s McGill University where he earned his political science degree, that he also became experienced in organizing demonstrations. During the Saint-Jean-Baptiste parade in 1968, for instance, Rose was a fellow sovereignty rioter who greeted the new, none-too-pleased prime minister candidate Pierre Trudeau with flying bottles. There, Rose met future FLQ wingman Jacques Lanctôt in the back of a police van.

And only a year later, Rose established La maison du pêcheur, a hippie hostel in Gaspé that would later become the FLQ’s Chénier Cell and centre stage for the October Crisis. But after multiple eviction notices, Rose left the business for something he saw as more ethically lucrative: to join the FLQ.

In 1970, in the wake of 13 FLQ sovereigntists being imprisoned, Rose and Lanctôt, among others, planned the kidnappings of two politicians, with the hopes of pressuring the release of the “political prisoners,” and spread awareness of their cause. The targets? British trade commissioner James Richard Cross and Quebec’s Minister of Labour and Manpower and Minister of Immigration Pierre Laporte.

Rose, however, wouldn’t stay in prison for long.

On Oct. 5, 1970, Cross was kidnapped and five days later Laporte was snatched from his lawn while playing with his nephew.

Rose’s FLQ promised the provincial and federal governments they would release the pair if the government released their political prisoners; otherwise, Laporte was the first to die.

As payback, members of the FLQ’s Chénier Cell strangled Laporte. His body was found in the trunk of a car a day after the War Measures Act was invoked.

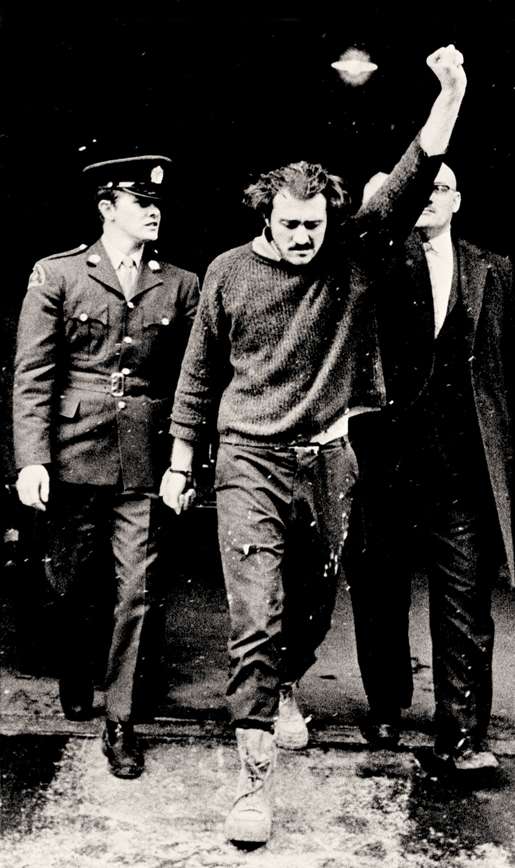

Cross was later released in exchange for the asylum in of the imprisoned FLQ members. Eventually, on Oct. 28, 1970, Rose was arrested. By March 13 of the following year, Rose was given two life sentences for the kidnapping and murder of Laporte.

But Rose’s activism didn’t stop. He fought for better living conditions, education and greater rights for prisoners, even organizing strikes among the detainees.

Rose, however, wouldn’t stay in prison for long because a 1980 re-investigation into the October Crisis found that he was not present when Laporte died. Rose was granted parole on Dec. 20, 1982.

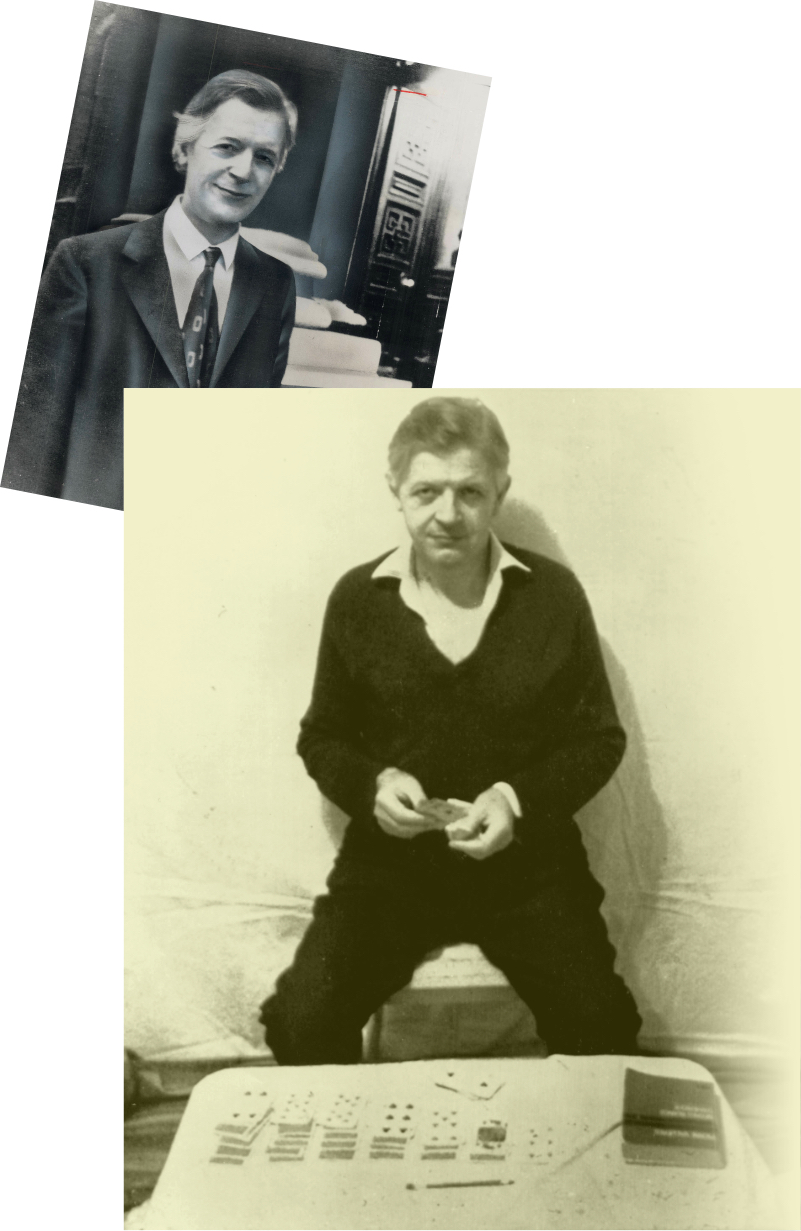

He continued his head-turning career in working-class activism. He became a union advisor and negotiator for the Confederation of National Trade Unions, a Université du Québec à Rimouski lecturer and, from 1996 to 2002, he was the leader of the Parti de la démocratie socialiste, a replacement for Quebec’s New Democratic Party.

And in between strikes, speeches and national fame, Rose found time to receive a Master’s degree in regional development from the Université du Québec à Rimouski and a PhD in sociology.

On March 14, 2013, as his family read him nationalist poems such as “Un Canadien errant” and “Nous étions le nouveau monde,” Rose died in a Montreal hospital.

“It shows once again the government’s lack of courage.”

While many Quebecers sympathized with Rose’s philosophy, the violent means to which he tried to enact that philosophy became a source of fiery debate.

“The October Crisis is a wound in the history of Quebec,” Bédard told The Montreal Gazette.

Even members of the Parti Québécois government did not comment on Rose’s passing.

“It shows once again the government’s lack of courage,” Québec solidaire party spokesperson and member of the National Assembly of Quebec Amir Khadir told The Toronto Star. “This is an important figure in the Quebec independence movement.”

But while many sang Rose’s praises, just as many were quick to point out his faults.

“Paul Rose is dead. Hallelujah! Good riddance. Long overdue. Couldn’t happen to a better guy,” wrote Mike Strobel in the Toronto Sun.

Gérald Larose, the former president of the Confederation of National Trade Unions, never condoned Rose’s methods, but he did have admiration for Rose’s skill and character.

“He was a man of conviction, he was an idealist,” Larose told The Toronto Star.

Love him or loathe him, one thing is certain: Rose changed Quebec’s forever.

For more on the October Crisis visit the award winning feature from Legion Magazine: https://legionmagazine.com/theoctobercrisis/

Advertisement