The First World War is known for stagnancy and stalemate—trench-bound days of misery and boredom punctuated by periodic terror and wholesale slaughter.

Soldiers from both sides lived in 2,490 kilometres of trenchworks winding southward from the North Sea through Belgium and France. For them it was a waiting game—a long, cold, mud-soaked ordeal broken only by the call to go “over the top,” a suicidal charge into a hail of bullets, usually at a whistle’s blow.

But for all its frustrating lack of movement and futility, the First World War was, technologically speaking, a turning point, marked more than any conflict before it by advances that changed the nature of war and, in some cases, peace.

The machine gun replaced the long gun as the most lethal small weapon on the battlefield; trucks and armoured vehicles, including tanks, replaced horses and carriages; fast artillery replaced cumbersome cannons; and airplanes ruled the skies.

Between 1914 and 1918—a technological blink of an eye—the Great War spawned the first chemical weapons, sophisticated communications and new advances in medicine and medical treatment.

“We propelled ourselves from the middle of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th in just four years in terms of military tactics and technology,” said Michael Boire, an adjunct professor of history at Royal Military College in Kingston, Ont.

The weaponry and tactics amounted to an industrial killing machine that claimed more than 17 million lives and wounded 20 million more—military and civilian, on both sides. About two-thirds of military deaths resulted from battle wounds, in contrast to previous wars, in which infection and disease accounted for most mortality.

This was largely due to three innovations: the machine gun, fast artillery and poison gas.

The Great War was the first war in which the mounted machine gun was ubiquitous. Tacticians failed to adapt early on and the fighting often ended with masses of charging soldiers falling before an onslaught of fire unprecedented in the annals of warfare. Progress was measured in yards more often than achieved objectives.

The machine gun was invented in the United States by Hiram S. Maxim in 1884. The British Vickers machine gun could spit more than 450 rounds a minute, 600 by war’s end. It is widely credited with ending the use of cavalry horses, its rain of fire so voluminous, wide and lethal that no horse-borne charge stood a chance against it.

The British Vickers machine gun could spit more than 450 rounds a minute.

Quick-firing field guns had been adopted by many nations by the time of the First World War.

Created by Russian Vladimir Baranovsky in the 1870s, they replaced cannons, labour-intensive weapons with their cannonballs, powder and fuses.

The newer artillery pieces were lighter and could be wheeled to new positions relatively simply. Even the largest siege weapons could be moved on road or rail by 1914.

They fired a cartridge containing a high-explosive shell and the propellant to launch it, a breech mechanism that allowed rapid reloading, smokeless powder so gun crews could see their targets, and recoil buffers so the barrel could quickly return to the same position after firing.

In 1887, an Elswick Ordnance Company 4.7-inch gun fired 10 rounds in 47.5 seconds, almost eight times faster than the equivalent five-inch breech loader. In WW I, on the other hand, a well-trained crew on a French 75 gun could fire 25 rounds a minute, or one nearly every two seconds. German field artillery alone is said to have fired 222 million rounds over the course of the First World War.

Bottom line: shells had greater range, were more accurate and explosive, and could be reloaded more rapidly. The lethal combination raised the casualty rates and created a new term in the medical lexicon—shell shock.

The growing importance of artillery is illustrated by the fact 20 per cent of all French soldiers were artillerymen at the war’s outbreak; by 1918, the figure was 38 per cent. Artillery was responsible for three-quarters of the war’s known casualties.

Infantry attacks were usually preceded by heavy artillery bombardments. But military strategists soon seized on a tactic first used in 1913 during the siege of Adrianople (Edirne) in the First Balkan War: the creeping, or rolling, barrage.

In theory, the artillery would shell territory just ahead of advancing forces. In reality, it was a dicey affair. Some 75,000 British troops were killed by their own artillery in WW I.

With a longer range and an increased role, artillery needed to reassess its spotting practices.

Reconnaissance balloons were supplanted by aircraft, which soon became the primary means of reconnaissance, opening a new age of warfare as rival aircraft began shooting at each other with everything from pistols to hand grenades. The first air war had begun.

By 1915, the Germans had developed mounted machine guns synchronized to fire at intervals through the propeller’s arc.

Over the course of four years, aircraft development took off, so to speak, as designers and engineers came up with fighters, trench strafers and bombers. The race for air superiority was in full swing and Germany had the advantage.

The Sopwith Snipe, the Sopwith Camel, the SPAD S.VII, the Albatros D.I, the Fokker Dr.I triplane, the Nieuport 17, among others, became legends of aviation.

Canadians Billy Bishop, William Barker, Roy Brown, Raymond Collishaw, Wilfrid (Wop) May and a host of others established the country’s early reputation in aviation, one that would grow in the years after the war as it developed specialized bush planes to deliver mail and supplies to remote communities across a vast and rugged landscape.

Parachutes had been around since 1797 and were used by wartime airship and balloon crews, but British authorities claimed they were too bulky to be used by airplane pilots.

This despite the fact that British railway engineer and inventor Everard Calthrop had developed the Guardian Angel, an aircraft parachute, before the war. The Royal Flying Corps had successfully tested it, but its commander, Sir David Henderson, would not permit it to be issued to his pilots. Calthrop was pressured not to publicize his invention.

Parachutes were not issued to British pilots until after the war.

With growing numbers of fighter pilots needlessly dying, Calthrop rebelled and in 1917 advertised his invention in several aeronautical journals. He revealed details of the RFC testing and noted that British pilots were being denied the right to use parachutes, even though they were willing to buy their own.

The Air Board set up a committee to look into allowing RFC pilots to use parachutes, and while some members of the committee favoured their use, the board decided against the measure. The official reasons were that the Guardian Angel was too bulky, not 100 per cent safe, and its weight would affect the performance of the aircraft.

An unpublished report, however, gave the real reason for the rejection, a confounding reflection of the attitudes of the day: “It is the opinion of the board that the presence of such an apparatus might impair the fighting spirit of pilots and cause them to abandon machines which might otherwise be capable of returning to base for repair.”

Major Mick Mannock (an ace who finished the war with 61 aerial victories and a Victoria Cross) and others became increasingly angry about the decision.

Mannock was a pioneer of aircraft combat tactics. He noted that he and other RFC pilots instead carried revolvers “to finish myself as soon as I see the first signs of flames.”

After two of his comrades died in an airborne collision, American ace Eddie Rickenbacker admitted in his journal to falling into “a very bad state of mind” knowing that a simple solution was at hand that “without question” would have saved their lives.

“Cannot help but feel,” wrote Rickenbacker, “that it was criminal negligence on the part of those higher up for not having exercised sufficient forethought and seeing that we were equipped with parachutes for just such emergencies.”

By 1917, parachutes were being used by pilots in the German, French and American air forces. As it was, parachutes were not issued to British pilots until after the war.

By the end of the war, the Germans had used 68,000 tonnes of gas; the Allies, 82,000. Chemical shells made up 20-40 per cent of all shells in the ammunition dumps of all armies, including Canada’s.

“There are 30 kinds of kinds of gas fabricated during the First World War,” said Boire. “Ten are lethal. But at no time do they become show-stoppers.”

Still, chemical weapons killed nearly 100,000 and wounded more than one million between 1914 and 1918. Many more died in the ensuing years from their lingering effects. Few got over what they saw and experienced on the Western Front.

Despite the horrors, the condemnations and apocalyptic warnings of their potential to annihilate, world powers failed repeatedly to negotiate an outright ban on chemical weapons, settling finally on the Geneva Protocol in 1925. However, while the agreement banned the use of chemical and biological weapons, it did not address their production, storage or transfer.

Today, chemical weapons are banned under the Chemical Weapons Convention of 1993. Signed by 188 countries representing 98 per cent of the global population, it outlawed their production, stockpiling and use.

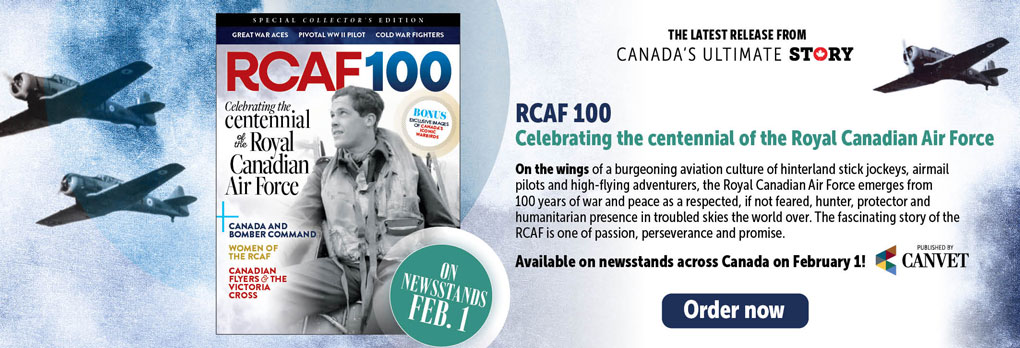

Advertisement