The Battle of Saint Eloi Craters in April 1916 was a gruesome disaster for the 2nd Division.

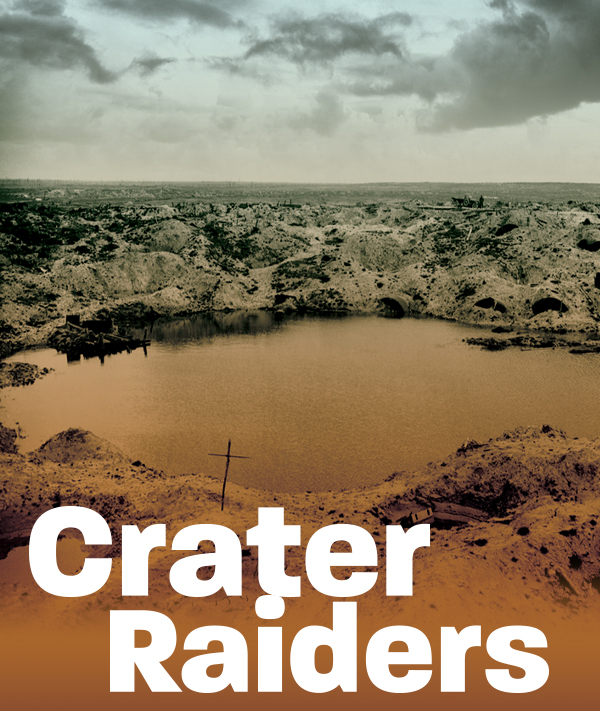

In early 1916, skilful British tunnellers worked hard to plant huge mines deep under German trenches. They blew them up in the Ypres Salient in Belgium on March 2, and the battle to control the resulting craters went on for some two weeks.

The commander of the British brigade finally pulled his men back to their original line, telling his headquarters that there was no point in holding the muddy interior of craters, as they were an obvious target for artillery.

That was sound advice, but General Herbert Plumer, commanding Second British Army, ignored it, and his tunnellers planted 31,000 kilograms of ammonal under the German trenches at Saint Eloi, five kilometres south of Ypres. Six mines exploded in the early morning of March 27, all but obliterating the enemy trenches and the troops holding them. Landmarks disappeared, trenches on both sides collapsed, and trench drains backed up, flooding shell holes and old craters.

The enemy spotted the error, moved reinforcements forward, and took control of Crater 5 on March 30. In the mud and mire, British and German soldiers fought hand to hand over the crater. Four days later, the Tommies controlled the ground.

Plumer’s plan had called for the 2nd Canadian Division, commanded by Major-General Richard Turner, VC, to take over the captured ground on the night of April 6. But the British brigade was so battered that Plumer moved up the relief to the night of April 3.

The 6th Canadian Brigade, commanded by Brigadier-General Huntly Ketchen, replaced the British. The handover was rushed, the lack of reconnaissance telling. That mattered because there was no real British line, only trenches and shell holes filled with waist-deep water and exposed to artillery fire from two directions.

“We had been left in a rotten spot by the British troops from whom we had taken over,” Lieutenant Frank McLorg, the 6th Brigade’s machine-gun officer, wrote home to Saskatoon on April 14. “They were all in and were withdrawn, and the position they had captured had not been consolidated at all, besides which our left flank was absolutely in the air. There were five mine craters and a German third-line support trench behind them occupied by us, and they were absolutely pounded flat.

“I have never seen and don’t believe there ever has been a more intensive bombardment over a small section…. I saw more of war and bloody murder than in all the rest of my time in France.”

On April 4 and 5, German guns heavily bombarded the Canadians, inflicting many casualties. The 27th Battalion’s commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Irvine Snider, thinned out his front line in an attempt to minimize the casualties, but it was to no avail.

“All that I can say is that the enemy artillery had obliterated the trenches,” Snider reported on April 6. “There were no troops left in the area to oppose them. What was left of the 27th Battalion…were so exhausted as to be incapable of resistance.”

Snider added that most of his officers, including him, had not slept in more than 100 hours. Making matters worse, the neighbouring 31st Battalion had no contact with Snider’s troops. It too suffered under the bombardment.

“The enemy was raining shells continually,” wrote Private Donald Fraser. “The trenches were in a quagmire and unconnected; communications were entirely broken down; there was no such thing as a firing trench…neither could materials be brought up.”

On the evening of April 5-6, after 17 hours of rain and what one soldier described as “painfully accurate” drumfire shelling, the 29th Battalion began to relieve the shattered 27th.

16th of April 1916.

Under heavy shellfire, the Canadians took craters 6 and 7 to the north of Crater 4, but erroneously reported that their objectives had been re-taken. “[We] firmly believed that we had made Nos. 4 and 5 secure,” a non-commissioned officer wrote later.

Without aerial photos, Ketchen and Turner were convinced their infantry held the objective. German prisoners taken on the night of April 7, however, told their interrogators that their comrades held craters 2, 3, 4 and 5, but apparently no effort was made to follow up on this information.

Aware that the 6th Brigade held the low ground in full view of the enemy, Turner then suggested to Lieutenant-General Edwin Alderson, the Canadian Corps commander, that he should pull back and shell the Germans in the craters or attack on a wider front.

Alderson tried to persuade Plumer, but the Second Army commander—who believed every inch of ground gained must be held—refused. Turner had to accede.

Attacks by the fresh 4th Canadian Brigade attempted to take Crater 3, and again reports came back to their headquarters that they had succeeded. In the morass of a shattered landscape, the soldiers had taken a crater, but not the correct one. The fighting continued, both sides struggling in the mire, the casualties heavy.

“We were walking on dead soldiers and the worse was they was [in] about three feet of mud and water,” Private Frank Maheux of the 21st Battalion wrote to his wife. One of those killed was his friend Anderson. “A piece of steel cut him pretty nearly in two.”

“Practically all of ‘A’ Company have been wiped out at Saint Eloi,” wrote Douglas Buckley of the 19th Battalion, who was wounded and recovering in hospital. “It gave me rather a jolt to hear all the boys I’d trained with had ‘gone west.’”

The Canadians’ wretched situation remained uncorrected until April 16, when the first air photographs in a week clearly revealed the actual situation.

All Canadian attempts to recapture the craters failed, and under a ferocious bombardment on April 19, the Germans took Crater 6. A week later, Alderson ordered that the craters be abandoned. Failures of command and control and inexperience had done in the 2nd Division. The defeat had cost the Canadians almost 1,372 killed and wounded. The enemy lost 483.

The 2nd Division’s poor showing at Saint Eloi persuaded the British high command that neither Turner nor Ketchen were capable commanders. Plumer ordered Alderson to sack Ketchen, but Turner refused to do the deed. Alderson then requested that General Douglas Haig, commander of the British Expeditionary Force, sack Turner and Ketchen for incompetence. But Turner had good political connections, and protests from Sam Hughes, Canada’s minister of militia and defence, and Sir Max Aitken, newspaper baron and member of Parliament, quickly made that impossible. There was concern that anti-British sentiment was growing among the Canadians.

“Turner is not the best possible commander of a division,” Haig wrote in his diary, “[but] I think it would be an error to change him at this moment.” He added that “all did their best and made a gallant fight.” That at least was true, but a scapegoat still was needed.

Poor Alderson, no Napoleon to be sure but relatively blameless in the debacle, got the chop and was replaced by Lieutenant-General Julian Byng. Ketchen and Turner survived; Turner until the end of November 1916.

The Canadians remained at Saint Eloi after the fighting died down, the craters still filled with corpses.

“Those whose smelling facilities are not the best,” soldier Wilbert Gilroy wrote to his father in May 1916, “have the advantage during the hot weather as [Saint Eloi] is not exactly a garden of roses.”

Advertisement