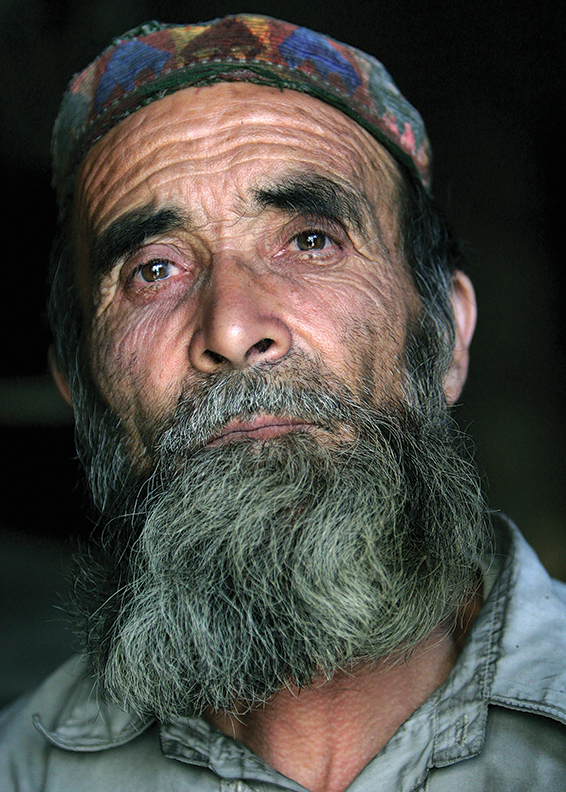

The faces of the long-suffering people of Afghanistan reflect their resolve and resilience

Kabul, 2004. Afghan mothers comfort sick and dying children in a hospital all but void of equipment and medicine. Across the street, fathers, banned by convention from the wards, sleep on concrete in a roofless bombed-out shell of a building, waiting for a white-coated figure to emerge and summon them to fetch the body of their dead child. Occasionally, a doctor delivers a slip of paper with a prescription scribbled in Dari, dispatching a desperate father into the city’s dusty streets to find medication on the black market—if he can afford it.

After almost three decades of war (now approaching four), life in Afghanistan’s capital was an epic tale of hardship, misery and death—sudden or slow—punctuated by grim resolve and unfailing resilience.

In the eastern Kabul district of Jangalak, 200 aging workers had returned to a sprawling factory complex to toil for next to nothing. The site once employed more than 2,000 people producing some 1,500 products. But after the Soviet occupation of 1979-89 ended, the civil war that brought the Taliban to power erupted (see page 104). The factory, with its daycare, progressive policies and fair pay, was destroyed then looted, its surviving equipment trucked off to Iran and Pakistan. The workers, most exceeding the era’s life expectancy of 47, were now breathing life back into the ruins, making manhole covers (Kabul’s had all been turned into bullets) and shopkeepers’ counterweights.

In a squatters’ camp on the city’s edge, widows and children, judges, labourers and former entrepreneurs had returned from internal exile, living in tents even as they built homes from the very soil beneath their feet.

In the streets, tradesmen eked out livings selling wares from converted sea containers; children machined parts for the country’s aging, ubiquitous Toyotas; the markets sold naan, rice, spices and halal meats. But for many Afghans, there was no income at all, no job but the task of securing the food and water they needed to survive another day.

Indeed, they were all survivors. They had survived war, malnutrition and disease. Disproportionate numbers had the mental and physical scars, and the missing limbs, to prove it. Virtually without exception, all had lost family and friends.

These hardships of war persist, altered but not eliminated by Canadian and other coalition troops who endeavoured more than to just rid Afghanistan of its terrorist and extremist influences, but to restore a quality of life all but forgotten to its long-suffering people.

These are the citizens of war.

Advertisement