The tank, Britain’s new secret weapon, spread fear across the battlefield during Canada’s first major offensive operation

In the minds of many, the First World War was characterized by a largely static front that stretched from the North Sea to the Swiss border and witnessed the unremitting use of machine guns, barbed wire, trenches and artillery barrages. Coupled with this was a dearth of new ideas.

Yet, the war did bring several innovations in equipment and techniques. It saw the first use of airplanes, tanks, long-range artillery, “creeping” barrages, wireless communications and flamethrowers.

During the infamous Battle of the Somme, a new technique and a new weapon were employed for the first time. And Canadian soldiers were among the troops who used them.

The background to the battle is generally well known. The July 1, 1916, opening confrontation was one of the largest single-day bloodbaths in history, with more than 57,000 British casualties by nightfall, including 710 soldiers of the Newfoundland Regiment.

The Somme offensive quickly turned into gruelling four-month war of attrition. Yet, instead of cancelling the assault, the commander-in-chief, British General Douglas Haig, renewed it. But first he needed fresh troops.

Haig called on the Canadian Corps, then deployed in Belgium’s deadly Ypres Salient. The Corps’ three divisions arrived on the Somme near the end of August. By then, the first and most of the second German lines had been captured, leaving the third still to be taken.

First Canadian Division, commanded by Major-General Arthur Currie, arrived and relieved the Australians along 3,000 metres of Pozières Ridge. In the first few days of September, the division’s 1st and 3rd brigades came under heavy shelling and frequent attacks.

At 6:20 a.m. on Sept. 15, after a massive five-day artillery barrage, the British attacked with 11 divisions along an 11-kilometre front between Flers and Courcelette. The Canadians’ role was a 2,000-metre-wide, two-division assault to capture the small, ruined village of Courcelette.

This battle marked the first major offensive operation for the Corps. Canadians had participated in earlier attacks at Festubert and Mont Sorrel, but they were either at battalion level with limited objectives or counterattacks to seize lost ground.

The troops’ advance soon outpaced the lumbering tanks.

Courcelette marked the debut of the creeping barrage and the caterpillar-like machine-gun destroyer—the tank. Earlier attacks had been overwhelmingly preceded by a standard artillery barrage, targeted on forward enemy positions. Such bombardments lasted for hours or even days and were intended to obliterate enemy troops and their defences.

When the barrage ended, the artillery shifted to targets in depth as the infantry charged forward in hope that most of the enemy soldiers were either dead or cowering in fear. But German troops usually remained safe in their deep bunkers and were back in their trenches to greet the advancing infantry with devastating fire.

The tank, meanwhile, had been developed in Britain in great secrecy to restore mobility to the battlefield. It was to accompany the infantry to provide direct fire support from a bulletproof platform and to overcome trenches and barbed wire.

The 28-tonne Mark I tanks were either “Male”—with two naval 6-pounder guns mounted in side sponsons plus three 8-millimetre Hotchkiss machine guns—or “Female”—carrying one 8-milli-metre and four .303 Vickers machine guns. Each crew consisted of one officer and seven men.

When Haig learned of their development, he immediately requested all available tanks. Although 150 tanks had been built by then, only 49 were shipped to the British commander. Thirty-two went into battle, distributed among the attacking divisions. Seven accompanied 2nd Canadian Division.’

Courcelette had been strongly fortified by the Germans and turned into a rabbit warren of interconnecting cellars, dugouts and deep galleries for protection. Two major trenches, Sugar on the left and Candy on the right, crossed in a giant “X” about 800 metres in front of the hamlet. The battered and strongly fortified remains of a sugar factory stood beside Candy Trench. These positions were the first objective of the Canadian attack.

On the right, 4th and 6th brigades from 2nd Division, commanded by Major-General Richard Turner, conducted the main attack toward Courcelette astride the arrow-straight Albert-Bapaume Road. The old Roman route marked the inter-brigade boundary.

The attack was supported by an unprecedented number of artillery guns for a Canadian operation. Second Division was allocated 114 18-pounders and 29 4.5-inch howitzers, while 3rd Canadian Division had 72 18-pounders and 20 4.5-inch howitzers in support. An additional 234 field and 64 heavy guns supported the two divisions.

The rolling barrage soon proved its worth. At zero hour, the 18-pounders opened fire with shrapnel 45 metres from the enemy’s front line. One minute later, the barrage moved to the front trenches and held there for three minutes before lifting 90 metres every three minutes until it reached the final objective.

Turner assigned three Mark I tanks to each assaulting brigade, with one in reserve. Three of the six tanks were male types, named Champagne, Chartreuse and Crème de Menthe, while the other three were female, called Chablis, Cognac and Cordon Bleu (Cordon Rouge in some sources). Two males and one female accompanied 4th Brigade; one male and two females were assigned to 6th Brigade.

Even though it was their first use, the tanks were not central to the attack and their movements were to conform to the infantry. In any case, the troops’ advance soon outpaced the lumbering tanks and soldiers had previously been told not to wait for them to catch up.

Within 4th Brigade on the division’s right, the 18th (Western Ontario) and 20th (Central Ontario) battalions reached Candy Trench by 7 o’clock, while the 21st (Eastern Ontario) Battalion captured the ruins of the sugar factory after fierce fighting. In 6th Brigade on the division’s left, the 27th (City of Winnipeg) and 28th (Saskatchewan) battalions secured Sugar Trench by 7:40.

The three tanks assigned to 4th Brigade were to advance up the Albert-Bapaume Road. One was to attack the sugar factory just to the left of the road, while the other two turned right to the boundary with a British corps.

One tank broke down short of the Canadian front line, while a second got stuck shortly afterward. The third one made it to the sugar factory to find it already captured. In accordance with orders, it returned to the Canadian lines to refuel and rearm.

The three tanks allocated to 6th Brigade were to advance along the brigade’s left flank to provide support to the infantry. Once this was done, they were to swing right and attack the sugar factory from the north. Two of them got stuck near Sugar Trench, but the other one reached the German trenches and killed several of the enemy before returning.

On the left, the role of 3rd Division, commanded by Major-General Louis Lipsett, was to provide flank protection for the main attack on Courcelette. The objective of 7th and 8th brigades was the heavily defended Fabeck Graben trench line. As 8th Brigade led the divisional advance across no man’s land, its units came under concentrated artillery and machine-gun fire.

On the division’s right flank with 2nd Division, the 5th (Quebec) Canadian Mounted Rifles (CMR) captured the northern extension of Sugar Trench, clearing the way for the 4th (Central Ontario) CMR to move through them and seize a portion of Fabeck Graben. On their left, the 1st (Saskatchewan) CMR made it to the edge of Mouquet Farm—popularly known to the troops as Mucky Farm.

The units of 7th Brigade then pushed through the 8th Brigade battalions. By nightfall, the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, plus the 42nd (Black Watch) and 49th (Edmonton) battalions, succeeded in capturing all but a 250-metre section of Fabeck Graben.

At 11 a.m., meanwhile, Lieutenant-General Julian Byng ordered the attack against the second objective, Courcelette itself, to recommence at 6 p.m. Another creeping barrage supported the attack. After first fighting through a line of German outposts in particularly vicious hand-to-hand combat, the 22nd (French Canadian) and 25th (Nova Scotia) battalions from 5th Brigade quickly advanced to the far side of Courcelette and reported it captured by 7:50 p.m.

While the two battalions fought off 11 violent German counter-attacks, the 26th (New Brunswick) Battalion played a deadly game of mopping up behind them in the ruins of Courcelette. In a frequently quoted remark, Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas-Louis Tremblay, the French Canadians’ commanding officer, wrote in his diary, “If hell is as bad as what I have seen at Courcelette, I would not want my worst enemy to go there.”

The battle continued on Sept. 16. First Division passed through Courcelette and replaced 2nd Division in the lead. It attacked the heights beyond the village, but made only minimal progress.

Third Division also continued its attack. Its objective was the next line of German defences: Zollern Graben, including a strongpoint at its western end: Zollern Redoubt. Zollern Graben was about a kilometre to the north of Fabeck Graben, although the two trench systems gradually joined northwest of Mouquet Farm.

That evening, 3rd Division launched a hasty attack toward Zollern Graben. Its soldiers were quickly pinned down by machine-gun fire and the attack failed. There was some success however, and units of 7th Brigade managed to capture the last 250-metre section of Fabeck Graben still in German hands.

Additional attacks continued over the next several days, but the Germans reinforced their positions and none succeeded. By Sept. 22, the Battle of Courcelette was over and Zollern Graben remained in German hands.

Courcelette was a rabbit warren of interconnecting cellars, dugouts and deep galleries.

The debut of the tank was less impressive. Of all the tanks employed during the larger British attack, the six allotted to 2nd Division were the most successful. Opinions of the effectiveness of the tanks seemed to depend on when and where an observer saw them.

While the actual effect of their firepower was minimal, they did inspire fear in the enemy. Lessons learned from their use at Courcelette led to technical and tactical improvements that ensured their use for the rest of the war and into the future.

The Battle of the Somme continued and finally petered out due to the onset of winter weather in November. By then, the Canadians had suffered 24,029 casualties, nearly 8,000 of them fatal.

On Sept. 9, 1916, Acting Corporal Leo Clarke and his section of 2nd Battalion bombers were covering the construction of a block in a newly captured German trench near Pozières. After all the Canadians but Clarke became casualties, 22 Germans attacked. Clarke emptied his revolver and two enemy rifles at them. When an officer bayonetted Clarke in the leg, he killed him and fought on. The remaining Germans ran away, pursued by Clarke, who shot four and took one prisoner. In total, he killed two officers and 16 men. Clarke was killed 40 days later and never learned of his Victoria Cross.

Bayonet man

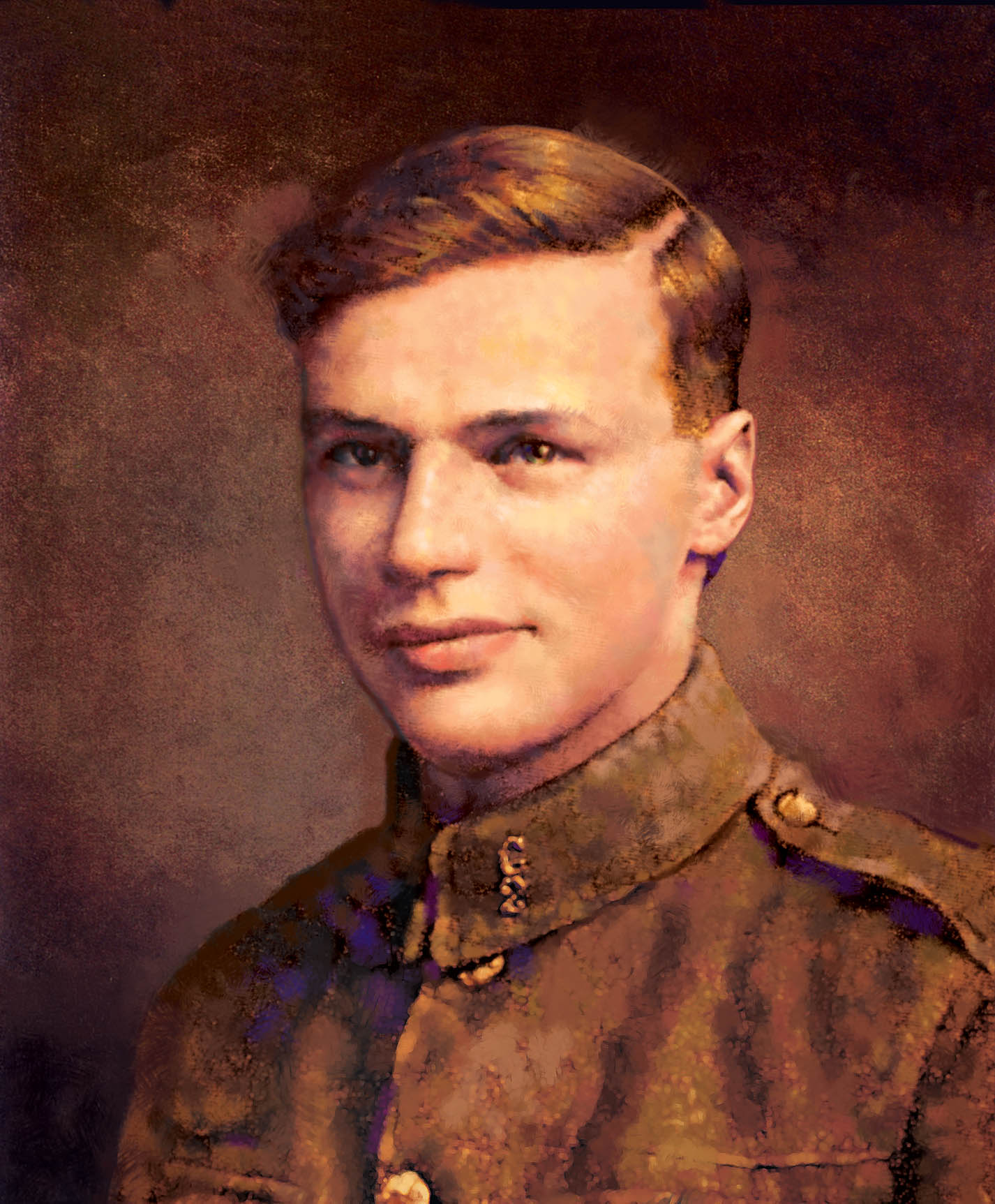

Private John Chipman (Chip) Kerr was bayonet man, leading a 49th Battalion bombing party on Sept. 16, 1916, in an attack against a German trench near Courcelette. He jumped into the trench, but a bomb thrown by a German blew off his right forefinger. With his group’s bombs running short, Kerr climbed out and ran along the parados. He verbally directed the bomb-throwing efforts of his companions and opened fire at point-blank range at the Germans. Sixty-two Germans surrendered and the final 230 metres of trench were captured. For his heroic actions, Kerr received the Victoria Cross.

Advertisement