When I was a young child of four or five, my grandfather would say to me in his cockney accent, “Swee’ar’, fetch me legs for me,” and I would dutifully bring him what he called “his legs”—steel rods screwed into the heels of his shoes for support with a leather cuff at the top which would rest just below the back of his knees. When he lifted up his pant legs to put on these supports, it revealed gaping holes in his calves. One hole was so large I could see from one side of his calf right through to the other. Somehow, I knew I wasn’t to ask any questions but that image has stayed with me all these years.

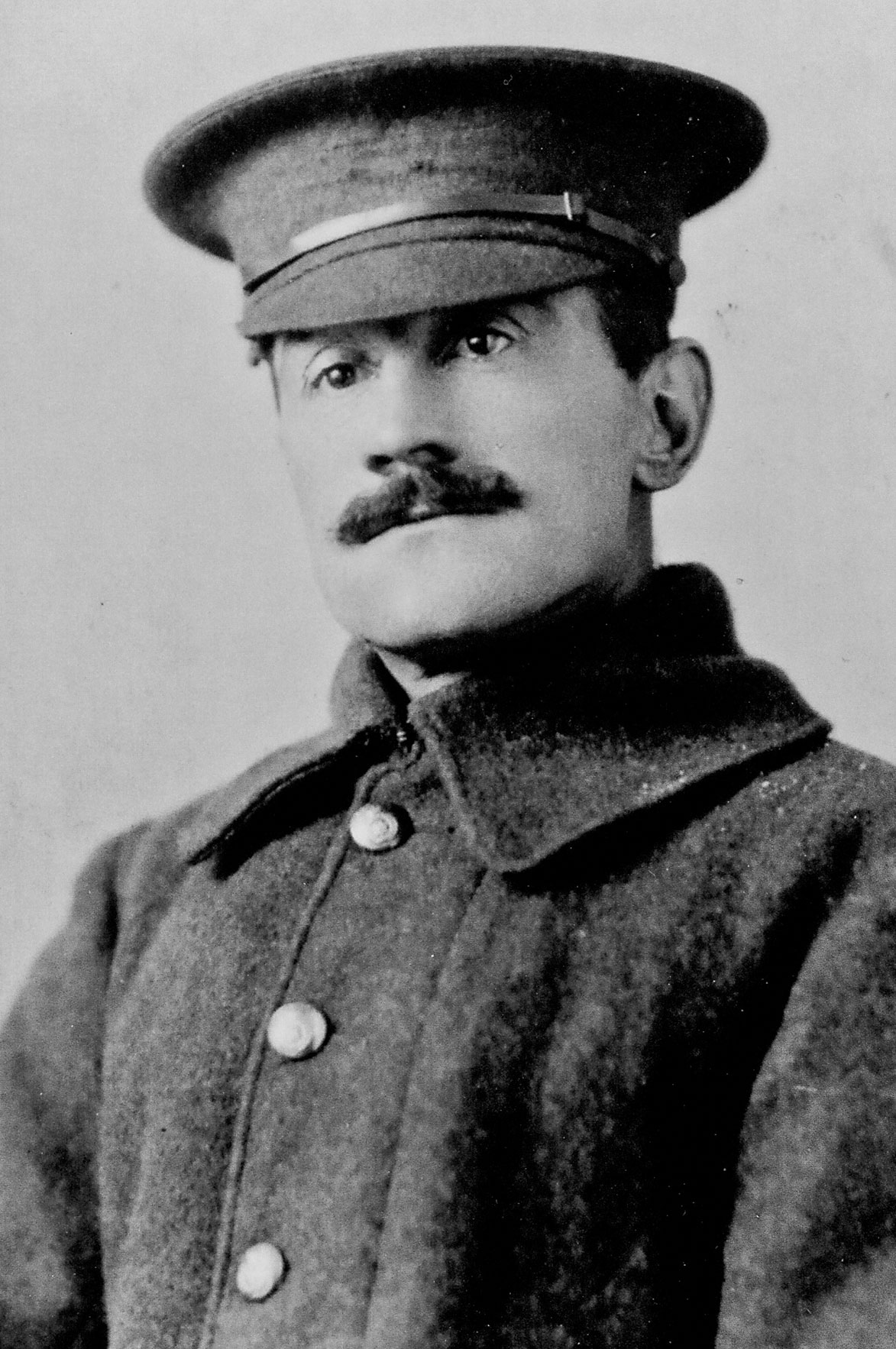

My grandfather, Ainger Roger Berry, the oldest of seven children, was born on March 15, 1879, in London, within the sound of Bow Bells. As a boy seaman in the Royal Navy in the early 1890s, he had his fair share of adventure travelling the world by sea. But after being “bought out” early for the remainder of his indentured service to the Royal Navy, he decided to venture to Canada, arriving in Montreal on the SS Bavarian in August 1904. Roger, who listed his profession as “carpenter” on the passenger list, headed for Manitoba, where he found work in Minnedosa. He eventually ended up in Victoria, where he and his brothers built a home large enough for the entire family of nine, including their aged parents.

By late 1914, he had met my grandmother and on June 7, 1915, they were married. Ten days later, he enlisted in Vernon, B.C., as a private in the 1st Canadian Pioneers Battalion, A Company. He was 36 years old. My grandmother went to Vernon with him, as two photographs attest—one of them showing a newly married couple with my grandfather in uniform.

After five months of training at Camp Vernon, Roger embarked overseas from Montreal on Nov. 18, 1915, and arrived in Plymouth 11 days later. Before he left, he removed his cap badge and gave it to my grandmother, who wore it on a ribbon around her neck.

After further training in England at Dibgate Camp on Saint Martin’s Plain near Folkestone in Kent, he left for France on July 5, 1916, as an acting lance-corporal.

Roger had been at the front about three months when a letter he had written appeared in the Daily Colonist in Victoria, dated Nov. 23, 1916. He had written it to his parents, James and Jessie Berry, and it was probably the last one he wrote while in the trenches.

Well, here we are, still on top and, so far, quite safe. I never had a bigger punch before. The Germans are leaving the country and have just received notice from us to keep on moving, while we continue to feed them their iron rations nightly. The enemy sends back some, of course, but up to the present gets very few of our boys. We took a few German prisoners the other day and they look pretty downhearted. We have the pleasure of living in their deep and well-made dugouts just now; in fact, I am enjoying the heat of a German’s stove. I expect he could do with it himself, but I am afraid he would have a hard time in the attempt to get it back.

I am pleased to say victory is ours all along the line, and the boys are just getting their own back. The enemy doesn’t like our new tanks at all, and in general he is fed up with the war. So are we for that matter, but he has simply got to take his medicine, and he certainly will get it.

Roger was the eldest of four brothers, all of whom served their country in various branches of the military. In January 1916, the youngest, Dick, lost an eye and was wounded in the groin. Six months later, on June 3, Charlie was killed near Ypres. Roger attempted to console his mother with an eloquent description of battle and sacrifice.

I am pleased to hear that brother Dick has arrived home. I found out how brother Charlie died, and I would ask you not to mourn, for death is the inevitable end of us all. Death faces us here every turn of the road, and yet the boys here meet it sternly and unafraid—bravely. The men here put me in mind of beautiful music. When they leap the trench and charge in the face of death, what can one be but proud of such men as these, and then in the clash of battle one can almost imagine hearing the faint, and then gradually louder, strains of music. So I would ask you not to mourn, for would you have had us different; would you have had us stay at home? Many mothers have lost their sons and will lose them until the end.

Writing to his mother, he seemed to be preparing to accept his own fate.

He had been assigned to the 4th Division, whose objective was to take Regina Trench. This was very close to the village of Courcelette, and in his military records, a statement reads, “Was buried by shell while running a transit on duty near Courcelette on the Somme.” This was Nov. 6, 1916.

How long he was buried under a massive pile of debris and mud before being discovered unconscious, I do not know. But it may have been a considerable length of time. Further details state, “Does not remember anything until he was put on train at Albert and given a hypodermic injection, was sent to Camiers.” The hospital train took him and hundreds of other badly wounded soldiers to the Casualty Clearing Station at Camiers, south of Boulogne, on Nov. 11, 1916. Searing hot shrapnel from the exploding shell must have embedded itself in his legs while he was running from one trench to another. Their removal most certainly would have created the gaping holes that I remember seeing as a child.

On Nov. 14, he was taken aboard the hospital ship HMHS Stad Antwerpen bound for England. One day later, on his medical case sheet, stamped “Western General Hospital” (Manchester), a medical officer, Dr. Rust, wrote his two-word diagnosis in very large letters, “Shell Shock” and underneath it the word “buried.” These two words—“shell shock”—were repeated throughout all his medical records.

After being admitted to five different hospitals and convalescent homes in various parts of England over a five-month period, his condition hadn’t improved. At his last hospital, the Canadian Military Hospital in Hastings, a Captain Walton made these observations: “A well-built, well-nourished man. Is extremely nervous, cannot keep quiet for a moment. Fine and coarse tremors, difficulty in speaking. Poor memory, suffers from headaches, sleeps badly, no appetite. Heart rate rapid.”

One hundred years ago, this was a new illness and it was occurring on a massive scale. Thousands of men were suffering the same symptoms and there was no known cure.

After being reviewed by three medical boards from January to March 1917, my grandfather was declared unfit for duty and was invalided to Canada for further medical treatment. On April 11, 1917, he was taken aboard the hospital ship HMHS Letitia at Liverpool and arrived 10 days later in Halifax. Special trains outfitted as hospitals transported the wounded men westward. Arriving in Toronto on April 24, 1917, he was admitted to Spadina Military Hospital, where he was placed in various units for three weeks. In May, he was moved to the Vancouver General Hospital, where he graduated from being a temporary outpatient to an outpatient. By June, he had finally arrived back in Victoria as an outpatient at Esquimalt Military Hospital.

Two years had passed since my grandfather had enlisted at Vernon, but a lifetime of uncertainty lay before him. Due to the severe effects of shell shock, he was never again able to hold down a job to support his family.

Roger was an eloquent man, and he felt it was his duty to advocate for the lowly soldier. An article appeared in the Daily Colonist on Dec. 6, 1917, soon after he had been discharged from the army. Under the title “Three Returned Men Support Liberals,” it stated that my grandfather, “Mr. A.R. Berry, and two other returning soldiers took the platform at the Princess Theatre in Victoria to speak out against the Borden administration and officers of the Canadian Army, Mr. Berry declaring that wounded men on the trans-Atlantic passage were put down in the hold while the upper decks were reserved for a few ‘autocratic officers.’”

Roger was referring to his own experience as a wounded soldier on his journey home by hospital ship eight months earlier. Later, in the early 1920s, he rode the rails to Ottawa along with thousands of other veterans to plead their case in the House of Commons for a war pension not only for themselves but for war widows as well. He was a man who was not afraid to speak up in order to improve the lives of others.

For the rest of his life, my grandfather suffered from the lingering and debilitating effects of shell shock, which no one could understand or cure, as well as the cruel criticisms and false accusations of being a malingerer.

While reviewing his documents, I discovered a significant fact—something that reflected his generous nature. When my grandfather was discharged from the army on Nov. 30, 1917, he was to receive the remainder of his War Service Gratuity, which amounted to $339.90. It was to be paid in three separate cheques over three months—a fair amount of money in 1917. For a man with such an uncertain future who had suffered greatly, this would have been a financial boost. I saw the handwritten instructions on his pay sheet with these words, “Send 3rd cheque to Soldiers’ Aid Committee, Toronto, Ontario.” He had requested that the money be used to benefit the lives of other men returning from the horrors of war.

My grandfather died on Nov. 2, 1968, just four months short of his 90th birthday and just four days short of the date, Nov. 6, on which he was buried alive at the Somme in 1916.

Four summers ago, I stood waist deep in a lush green wheat field in the area that was once Regina Trench near Courcelette. I reflected on my grandfather—on all that he had witnessed and experienced, and on the man he was at that time: newly married, nearly 40, yet willing to volunteer and sacrifice it all. I felt immense admiration for his courage, determination and loyalty. His generosity inspired others; this is the legacy he leaves for all of us. I am very proud to say he was my grandfather.

Advertisement