At 3:35 a.m. on July 6, 1942, four P-40 Kittyhawk fighters scrambled out of the air station at Mont-Joli, Que., and went U-boat hunting. One of them never returned.Near the end of their two-hour patrol, Kittyhawk AK915, piloted by Squadron Leader Jacques Chevrier, went down in up to 70 metres of water, less than five kilometres off Cap-Chat, Que. The wreck was never found, a cause was never determined, and Chevrier’s remains were not recovered.

“We’re not going to find a perfectly preserved airplane sitting down there, but at least it solves the mystery,” said Lee Walsh, a Toronto-based society member who has been spearheading efforts to answer 80-year-old questions surrounding the disappearance and bring closure to Chevrier’s story.

“They’ve found the three vessels that were sunk that morning, but they haven’t found Chevrier. We have the equipment today to go do that stuff,” said Walsh. “It’s a lot easier than it was in 1942. The sad thing is we have no records of where they were looking. There are a lot of things missing in the official crash report.”

The 18 merchantmen killed in the Nicoya and Leto sinkings in May were the first to die as the result of hostile action on Canada’s inshore waters since the War of 1812.

Less than eight weeks later, Kapitänleutnant Ernst Vogelsang guided U-132 into the gulf, where he discovered two convoys converging in the waters off Cap-Chat, at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River west of Anticosti Island.

“We’re not going to find a perfectly preserved airplane sitting down there, but at least it solves the mystery.”

Vogelsang fired his first volley of four torpedoes at 12:21 a.m. Two missed their mark 1,500 metres away—the Greek freighter Anastassios Pateras, loaded with grain and trucks in Montreal. One struck the vessel starboard between the cross bunker and the stokehold. Anastassios Pateras sank within 10 minutes.

The last of the four torpedoes tore a 1.2-metre hole in the starboard hull of the Belgian freighter Hainaut. Filled with general cargo, its deck covered in trucks, Hainaut disappeared in 20 minutes. Four of the 74 crew aboard the two ships died.

The convoy scattered; some vessels turned back. But Vogelsang wasn’t finished.

At 1:45 a.m., the German found the British steamer Dinaric continuing on its original course for Sydney, N.S., with its load of timber and steel. The vice-commodore, second-in-command of the ragtag collection of merchant vessels, was aboard.

Vogelsang fired a single torpedo, striking Dinaric amidships on the starboard side and killing four crew. The ship immediately began to settle on a 25-degree list to port, then righted itself. Dinaric stayed afloat for three days before it foundered.

The Bangor-class minesweeper Drummondville took up the chase after U-132. Its commander, Lieutenant (N) James P. Fraser, caught the sub in the glare of a star shell and tried to ram it. Vogelsang slipped beneath the waves just in time.

But Fraser had the German in his sights. Drummondville dropped a half-dozen depth charges, severing the main line in the enemy’s buoyancy tanks. The Type VIIC U-boat plummeted to 185 metres, near the type’s crush depth. The desperate crew managed to stabilize the boat at 180 metres and began the anxious wait that only submariners, especially U-boat men, can know.

As the sounds of Drummondville’s propellors faded into the distance, Vogelsang ordered the buoyancy tanks blown and U-132 rose to the surface. The heavily damaged boat made a run for it as fast—or as slow—as its wounds would allow.

Drummondville was off trying to reassemble the convoy. Just before Chevrier’s flight took off at 3:35 a.m., the ship’s ASDIC picked up the sound of U-132’s diesels. The Canadian sped toward the contact and fired a star shell, but U-132 was already gone.

Chevrier’s flight spotted only Dinaric still afloat with survivors in the water.

“They’ve found the three vessels that were sunk that morning but they haven’t found Chevrier.”

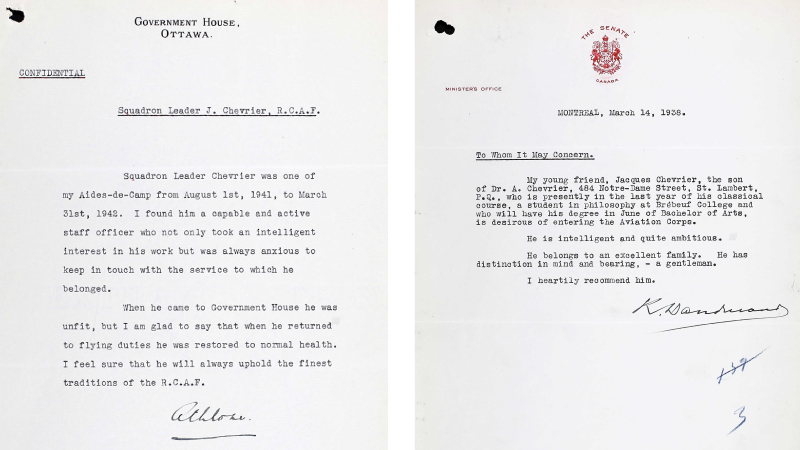

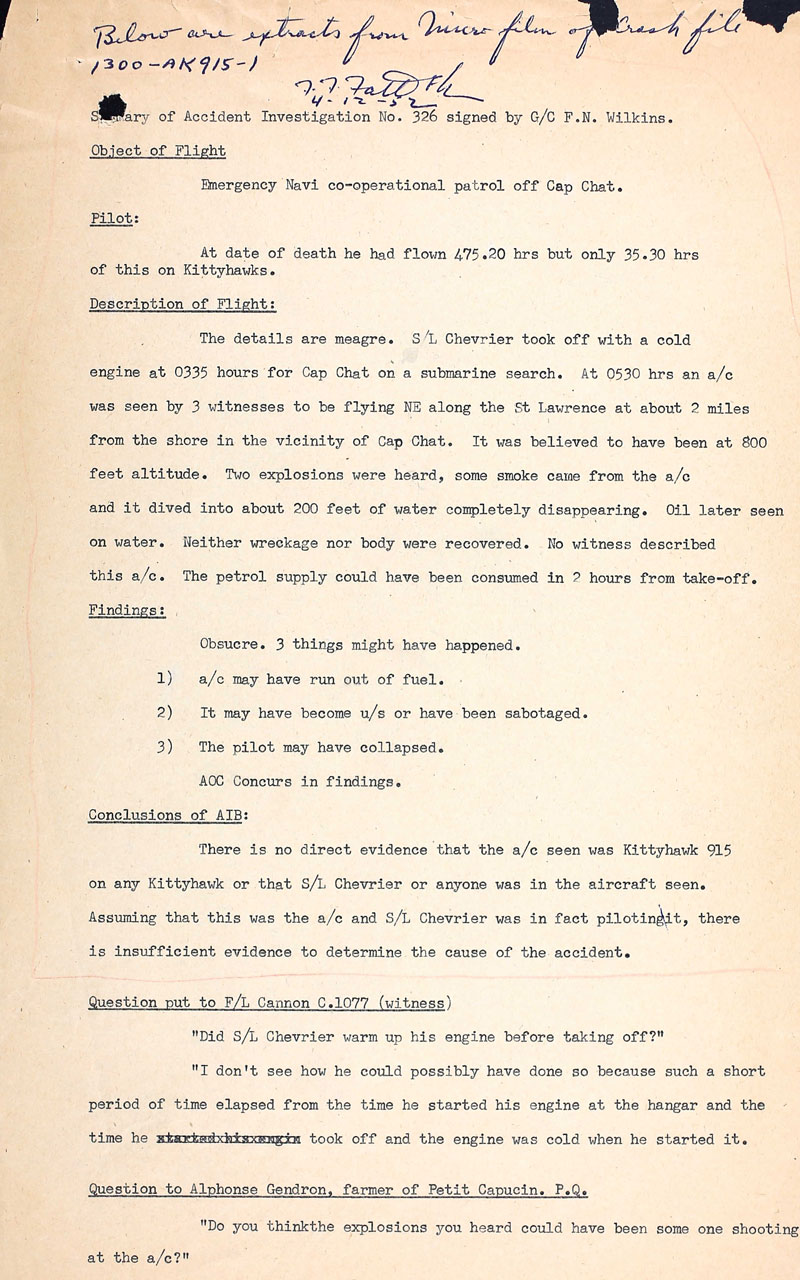

According to the Royal Canadian Air Force investigation, signed by the chief inspector of accidents, Group Captain F.S. Wilkins, on Aug. 4, 1942, Chevrier was “in an excited condition” before he led the P-40s of 130 Squadron out on the fateful patrol.

“The details are meager,” the investigators wrote. “S/L Chevrier took-off with a cold engine at 03:35 hours for Cap Chat on a submarine search.

“At 05:30 hrs an a/c was seen by 3 witnesses to be flying NE along the St. Lawrence River at about 2 miles from shore in the vicinity of Cap Chat. It was believed to have been at 800 feet altitude.

“Two explosions were heard, some smoke came from the a/c and it dived into about 200 feet of water completely disappearing. Oil later seen on water. Neither wreckage nor body were recovered. No witness described this a/c.”

Farmer Alphonse Gendron was asked if the explosions he heard that morning “could have been someone shooting at the aircraft.”

Gendron was unequivocal. “No,” he said. “The water was calm and there was no boat in the neighbourhood. The aircraft was too far from shore for someone to hit it from shore.”

“Did S/L Chevrier warm up his engine before taking off?” an investigator asked him

Said Cannon: “I don’t see how he could possibly have done so because such a short period of time elapsed from the time he started his engine at the hangar and the time he took off and the engine was cold when he started it.”

Cannon would go on to serve with the International Control Commission monitoring the treaty that ended the war between France and communist-backed troops seeking independence in French Indochina, the precursor to America’s 10-year war in Vietnam. He was stabbed to death in his bed in Hanoi on April 12, 1957.

Based on the testimony of an aircraftman who said Chevrier’s tanks were full before take-off, the crash report noted that the plane set out on about two hours of fuel.

The planes were operating with a 6,000-foot ceiling and 20 miles’ (30 kilometres) visibility. Winds were light. Chevrier, 24, was one of “The Few” who’d flown more than two dozen sorties with 110 Squadron, Royal Air Force, and No. 1 Squadron, RCAF, in the 1940 battle to save Britain from imminent defeat by the forces of Nazi Germany.

The RCAF report regarded the Saint-Lambert, Que., native as an “above average” pilot in good health with 350 solo hours on 25 different aircraft, 35.5 of them in P-40s.

“There is no direct evidence that the a/c seen to dive into the St. Lawrence River was Kittyhawk AK915 or any Kittyhawk, or that S/L Chevrier or anyone was in the aircraft seen,” said the report.

“Assuming that this was the a/c and S/L Chevrier was in fact, piloting it, there is insufficient evidence to determine the cause of the accident.”

Chevrier was listed as “missing, presumed dead.” He was officially declared dead in January 1943.

“Two or three explosions were heard from the aircraft in rapid succession, then aircraft dove into the river with black smoke coming from the engine.”

A search for Chevrier’s aircraft was conducted during the 1942 investigation, but RCMP and RCAF records don’t show where they dragged the river bottom using a hook and chain.

Based on eyewitness interviews, the historical society team has estimated that, after circling the village with a “rough motor” at about 600 feet (183 metres), Chevrier crashed about half a kilometre from U-132’s estimated position.

“Two or three explosions were heard from the aircraft in rapid succession, then aircraft dove into the river with black smoke coming from the engine,” it said.

“The Adjutant of RCAF Station Mont-Joli witnessed the crash, and left his cows to row out to the crash site and only found an oil slick at approximately where his favorite fishing spot was.”

The adjutant estimated the depth at around 40 feet (12 metres), not the 200 feet listed in the RCAF report. While interviewing witnesses 20 years ago, Michel Roy, a society team member from neighbouring Matane, Que., uncovered the story of a local fisherman who believed he’d spotted a “silver plane” on the river bottom.

Local lore is, in fact, rife with sightings. Scuba divers have reported scattered metal on the bottom.

Walsh said more clues might be found in the papers of Ernest Bertrand, former postmaster general and later federal fisheries minister. Bertrand’s son Guy was a 130 Squadron pilot, flying the last plane out on Chevrier’s final mission.

Guy Bertrand was killed in a flying accident a few months later, but Chevrier’s father and a close friend, Dr. Stephen Langevin of Montreal, had persuaded the MP to contact authorities and urge them to extend the search for the squadron leader’s plane.

Walsh said Langevin thought he’d found the aircraft using an acoustic device. The official search continued into the fall. Nothing was found.

Roy and Walsh combined their research and now believe they have narrowed the potential crash site using GPS. The pair, who’ve been on the case for 20-plus years, are now talking to dive societies, aircraft recovery groups and potential financial backers with an eye to launching an expedition to find AK915.

There is a healthy market for vintage medals. A set somewhat more collectible than Chevrier’s potential grouping fetched over C$46,000

Chevrier’s father would receive two posthumous medals awarded to his son—the Canadian Volunteer Medal with Overseas Bar and the War Medal (1939-45).

“Issuing and replacing Second World War medals is strictly regulated according to criteria established by the United Kingdom and adopted by the Commonwealth countries, including Canada,” MacAulay wrote. “These criteria include a list of eligible next of kin to whom medals can be sent posthumously.”

The list, he noted, does not include Chevrier’s last living relatives, his nieces.

“Sadly,” wrote the minister, “as there is no surviving eligible next of kin, it is no longer possible to award these medals. Please be assured this in no way diminishes the nation’s gratitude for Squadron Leader Chevrier’s service and contributions.”

Britain and other Commonwealth nations have loosened restrictions on distribution of decorations to next of kin. But Veterans Affairs Canada never did. Only the widowed or the eldest living child, sibling or grandchild can receive posthumous medals.

Ottawa stopped issuing First World War medals in 2009, but the Canadian mint is still producing awards for the Second World War.

There is a healthy auction market for vintage medals. A set somewhat more collectible than Chevrier’s potential grouping fetched more than C$46,000 at a May 18, 2022, auction in the U.K.—well beyond the wherewithal of a notable competing bidder, the Battle of Britain Museum in Hawkinge, Kent.

“Unfortunately, he died and they never found him. It was a very poignant day in Canadian aviation history.”

—

Pre-order U-boats attack: The Battle of the St. Lawrence, Canvet Publications’ latest volume in its series, Canada’s Ultimate Story. Click here to place your order for home delivery now or pick up a copy on newsstands in August.

Advertisement