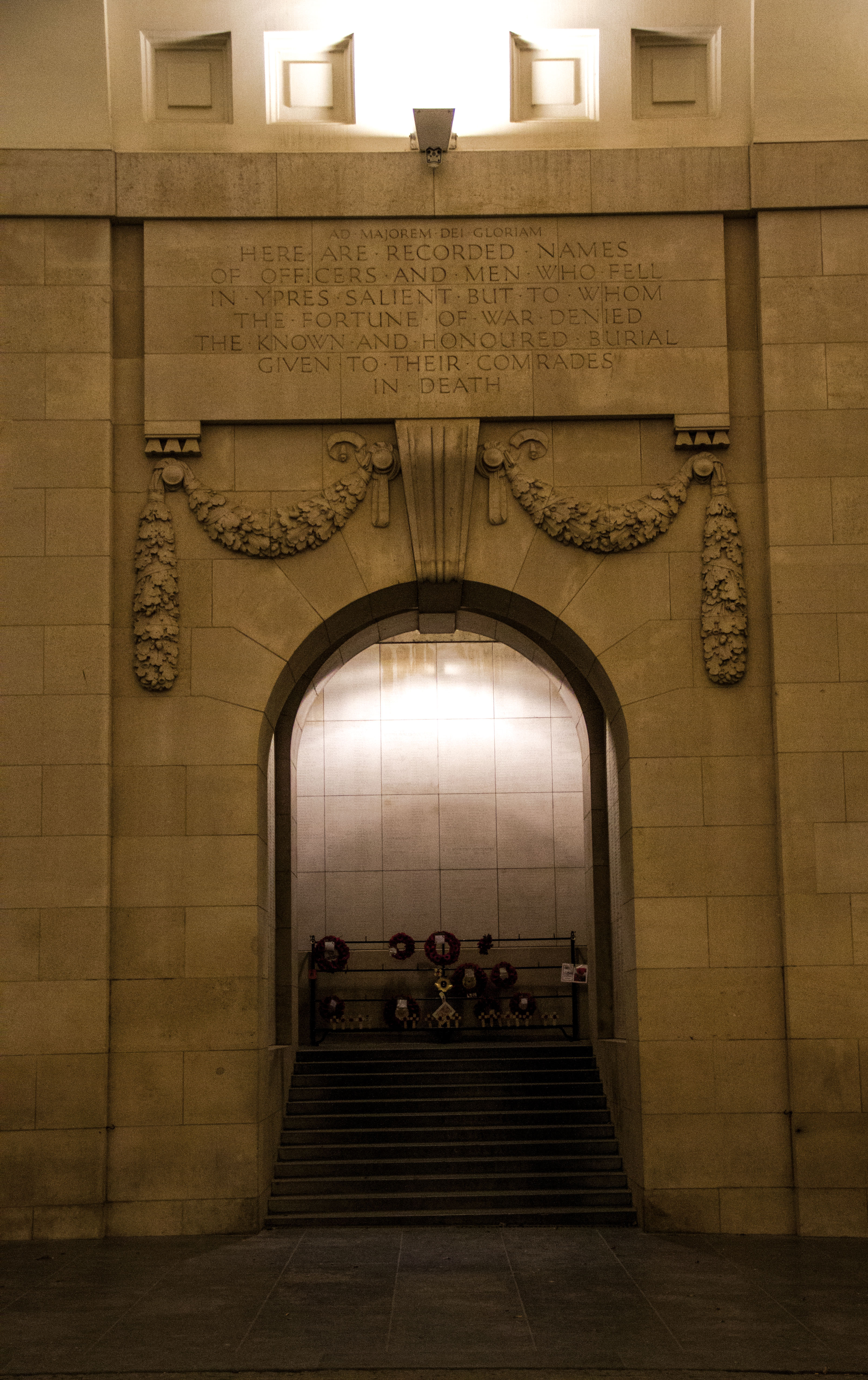

The Menin Gate in Ypres, Belgium—

a memorial to 54,395 Commonwealth soldiers

with no known grave—is the setting for a daily

ritual of remembrance

It is 5:00 a.m. and the streets of Ypres, Belgium, are dark and quiet. I’m out early today, on my way to the Menin Gate. I want to experience the memorial in solitude, before the crowds gather this evening for the daily “Last Post” ceremony.

It’s mid-October, the air is crisp and the cobblestones are glistening from last night’s rain. Warm light pours from a shop farther down the street, and the smell of freshly baked bread fills the air as commuters stop in for morning treats. Passing the shop, I see busy bakers filling the racks and beautiful pastries lining the windows.

At the end of the street, I turn onto Menenstraat (known as the Menin Road to the soldiers of the First World War). I can’t help thinking of the soldiers who walked this very route on their way to the battlefields of the Ypres Salient a century ago…marching to an uncertain fate.

The Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing appears in the distance, dramatic lighting accentuating its arches and columns. Designed by architect Sir Reginald Blomfield with sculptures by Sir William Reid-Dick, the memorial was inaugurated by Field Marshal Lord Herbert Plumer on July 24, 1927.

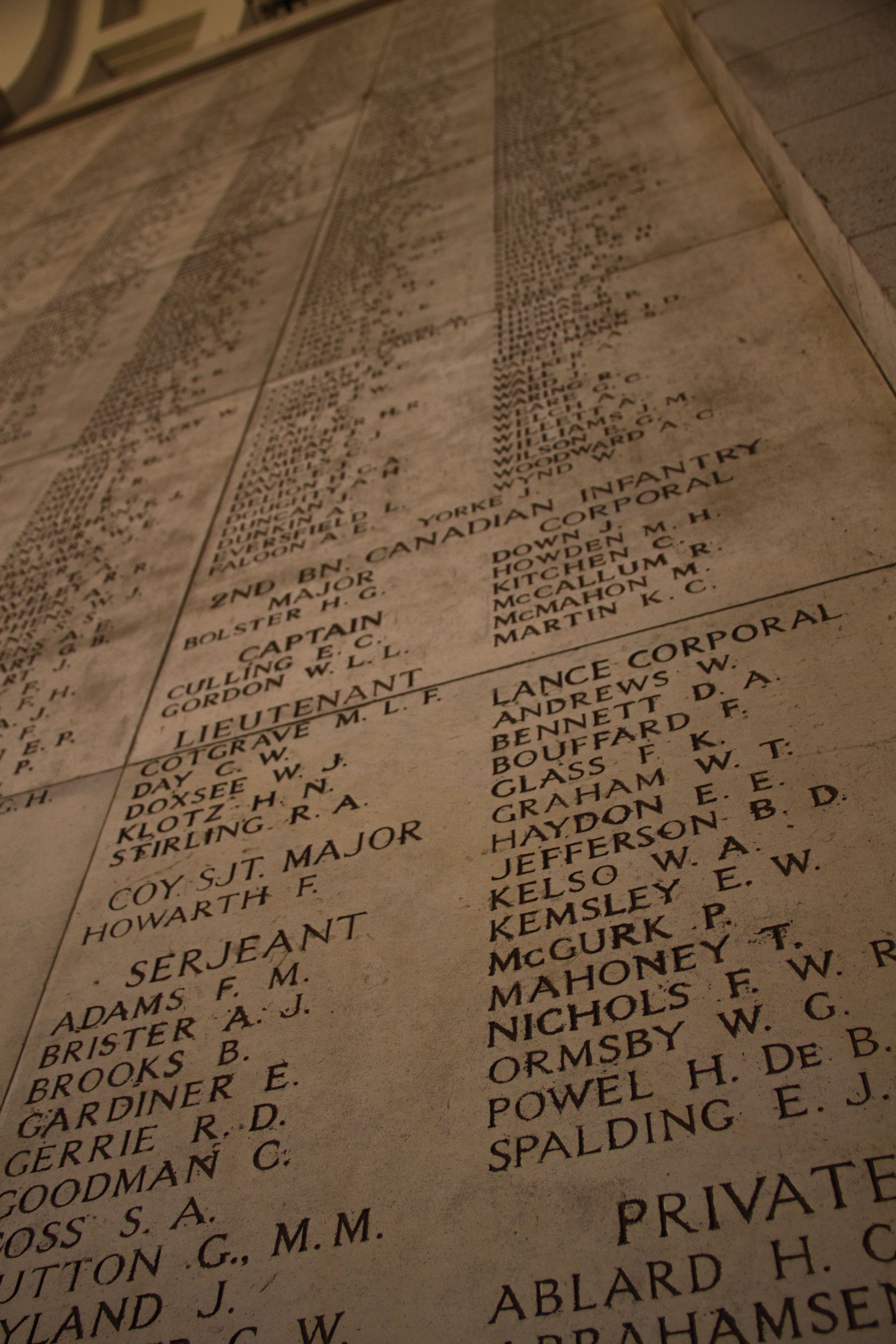

Etched on its walls are the names of 54,395 Commonwealth soldiers—the dead with no known grave. These are the missing, the soldiers swallowed by the mud, their remains unrecognizable or simply disappeared. The horror these men faced is unfathomable. In April 1915, Germany unleashed the first gas attacks in this region. Waves of chlorine gas drifted over the front lines. The Allied soldiers, choking, gasping for air, initially had no defence for such warfare. Fear would have run rampant through the ranks, yet despite it, they fought on.

It is staggering to see the names, floor to ceiling, row on row. They seem endless. Each is etched meticulously into panels of Portland limestone from Dorset, England. I look for Canadians and scan for my surname. I have no family ties to the First World War—at least none that I am aware of. My father served in the United States Army. He was a sergeant in the 101st Airborne Division in the early 1960s. Like so many of the men who returned home after deployment, Dad doesn’t talk about his time in the military. Some stories can only be shared with men who had similar experiences.

My maternal grandfather, Myles Hunter, was in the Canadian army during the Second World War. He didn’t see action, but that didn’t stop him from telling his grandkids tales of fighting in the war. He passed away in 2008, and I miss those stories dearly. After his death, I understood why he fabricated those tales. He had enlisted and trained and was combat ready, but he didn’t have the opportunity to deploy because, thankfully, the war was drawing to a close. He was ready to fight for the greater good, but didn’t get the chance. I respect that and will always look back fondly on those conversations.

Fear would have run rampant

through the ranks,

yet despite it, they fought on.

There isn’t a Duprau to be found on the walls of the Menin Gate, so I begin to look for Hunter, my grandfather’s surname. There are a number of Hunters listed as Canadians, and I wonder if there’s a chance that I am related to one of them, but I’m sure I would have heard stories from my grandfather if that were true.

I explore every inch of the memorial, snapping photographs of interesting angles and mementos of commemoration left from previous ceremonies. There are names on every surface, through each corridor, up the stairs on each side and on the outer walls. I am overwhelmed, wondering how so many could ever go missing.

Tires rumble on the cobblestones and headlights glare as cars pass through the memorial. Ypres is awake. It’s time to make my way back to the hotel.

Such a beautiful city, it’s hard to believe it was reduced to rubble a century ago. Shortly after the war, work began to rebuild the city and soon it was again a jewel of Belgium. The tower of the famed Cloth Hall rises in the distance. Restored to its original state, it is the focal point of Ypres.

Along Menenstraat, tucked between restaurants and chocolatiers, are souvenir shops featuring poppies on everything from T-shirts to mugs. Ypres is the city of remembrance. Everywhere you look, you are reminded of the war. The Cloth Hall houses the In Flanders Fields Museum, whose purpose is to tell the soldier’s story. Not for the faint of heart, it is a place where you can immerse yourself in the lives of First World War soldiers, and witness their hardship and demise.

I pass the bakery again, now full of patrons, bicycles in a neat row outside, the once-full racks of baking nearly bare. It’s time for coffee and a treat.

Back in my hotel room, I pull out my laptop and search the Menin Gate database for information on the Hunters I found on the wall. There are six listed as Canadians, Alfred, Cecil, George, James, J.C. and J.S.

I find my way to Cecil’s attestation paper and learn that he enlisted at the age of 21, served with the 4th Battalion, 1st Central Ontario Regiment, and was killed seven months later, just days after his 22nd birthday. Official records indicate that he was wounded in an attack near the Belgian village of Saint-Julien on April 23. He was never seen again.

Oddly, I feel a connection to Cecil. There are similarities between us. We come from farming families, lived in Ontario, are the same height and nearly share the same birthday: April 9 and 10, 77 years apart. I search for his last known residence, but can’t find any additional information. I will certainly dig further when I get the chance.

As it approaches 7:00 p.m., I go back outside to join the crowd making its way down Menenstraat toward the memorial.

The Menin Gate ceremony is a big part of daily life in Ypres. Shortly after the memorial was inaugurated, a group of prominent Ypres citizens wanted to express gratitude to the soldiers who fought and died in the region. The first ceremony took place on July 1, 1928, and carried on daily for about four months. In 1929, it was reinstated and has been performed every day since, the only exception being the period of German occupation during the Second World War.

Cameras flash, tears well,

all eyes are fixed on the buglers.

Then come the pipes.

Men, women and children, some carrying wreaths, flowers and other small tokens of commemoration, converge on the memorial. It’s good to see so many young people with their parents, pointing to the walls, discussing the meaning of the memorial. I hear several different languages as well. Many countries were affected by the war and many of their citizens have come to witness the ceremony and experience what Ypres has to offer.

A hush comes over the audience as the ceremony begins. Four buglers, members of the Ypres Fire Brigade, form up at the eastern entrance of the memorial. As they sound the “Last Post,” the haunting melody envelops us. Cameras flash, tears well, all eyes are fixed on the buglers. Then come the pipes. The notes reverberate around the walls and arches, stirring emotions like no other instrument can. Bagpipes lead soldiers into battle and memorialize them when they have fallen. I’ve always loved them. Maybe it’s my Scottish background and the fact that my grandfather always wanted me to learn to play them.

A veteran makes his way to the centre of the great arched monument and recites The Exhortation: “They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old. Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them.”

As he exits, a procession of young and old carrying wreaths makes its way up the north stairwell to pay tribute. The crowd remains silent. When all wreaths are placed, the buglers, still in formation, begin to play “The Rouse.” I glance around the crowd and notice an elderly veteran in uniform, leaning on his walker, his wife clinging to his arm. His eyes are wet with tears.

The words “We will remember them” linger with me. Will we? Will we remember them? I wonder if this war will one day find itself in the back pages of history? Our First World War veterans have long passed and it is our duty to ensure their sacrifice is never forgotten. The emotional expressions on the faces of the dispersing crowd assure me that these people will not forget. Remembrance is alive and well in Ypres.

On the way back to the hotel, I stop at a pub for a drink and a chance to reflect on the events of the evening. I notice a group of men, maybe a dozen or so, gathered around the bar. They are all dressed in suits, white shirts and identical ties, and range in age from what looks like late 20s to mid-80s. After ordering a drink, I ask them who they are and why they are all dressed the same. In thick British accents, they tell me they are from a small village in England. Each year, they travel to Ypres to commemorate a different soldier who fought and died in the war. Each time, they select a different tie to represent a particular soldier. They have several trips ahead of them to complete their list and the oldest one, who must be pushing 85, says he hopes to make it to the end. I ask them what they’ll do when they reach the end of the list? “We will start again,” one of the younger men says.

Needless to say, I was compelled to buy them a round. This is the type of dedication to remembrance that we need to preserve the memories of those soldiers. I share a drink with them and decide to call it a night, one that will live with me for my time.

I’m amazed that the men of our country left their families and livelihoods, with little or no experience and under-equipped, to fight a war in foreign lands, simply because it was asked of them. I’d like to think that if the need arose today, I would be one of those men, to fight bravely in horrific conditions and against incredible odds.

Driving out of Ypres, I gaze across the fields of Flanders. I think about those men, the more than 54,000 soldiers named on those walls. I think of Cecil Hunter, still out there somewhere, among the trees, in the fields of poppies. And I say thank you. You will not be forgotten.

Advertisement