Thinkers, scientists and negotiators: arms control after the Second World War

There is a single principle that, to one degree or another, underlies virtually all the 25 or so nuclear weapons treaties signed since the United States dropped the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. It’s called mutual assured destruction or, in what one critic of the day described as a “cleverly pejorative acronym”: MAD.

It is a deterrence principle that the launch of nuclear weapons by either side in a dispute would inevitably lead to the mass destruction of both. Older generations know it well. The term was coined in 1962 by Donald Brennan, a strategist at the Hudson Institute, a conservative think tank in Washington. In short, he said, America and the Soviet Union were each holding “the other side’s population hostage.”

Brennan was essentially an independent thinker, working outside the channels of government policy and diplomatic negotiation. And for all the treaties and agreements signed over the years, it is his rather twisted principle, more than any other, that has prevented a nuclear holocaust of unimaginable proportions. “Throughout much of the Cold War, U.S. declaratory policy (i.e., what policymakers said in public) closely approximated MAD,” wrote Columbia University professor Robert Jervis in the journal Foreign Policy in 2009.

“The view, most clearly articulated by then Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, was that there was little utility in adding strategic weapons above those needed for MAD, that nuclear superiority was meaningless, that defense was useless, and that this bizarre configuration was in everyone’s interest.”He said the implication was that the U.S. “should not only avoid menacing the Soviets’ retaliatory capability but also help the Soviets make their weapons invulnerable.”Madness, indeed.The anti-nuclear movement began in high places with the release of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto in London on July 9, 1955, by mathematician, writer and social conscience Bertrand Russell. Coming as Cold War tensions heated up, it emphasized the dangers posed by nuclear weapons and urged world leaders to seek peaceful resolutions to international conflict. Eleven distinguished intellectuals and scientists signed the declaration. Albert Einstein signed it just days before he died in 1955.

Shortly after, philanthropist Cyrus S. Eaton responded to the manifesto’s call for a conference, offering up his seaside compound in his birthplace of Pugwash, N.S. “Your brilliant statement on nuclear warfare has made a dramatic worldwide impact,” he told Russell. The first session of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs was held in July 1957, bringing together 22 eminent scientists from 10 countries.

Nuclear disarmament would be a prevailing theme of the conferences, which—along with founder, Polish-born physicist Joseph Rotblat—would jointly receive the 1995 Nobel Peace Prize “for their efforts to diminish the part played by nuclear arms in international politics and, in the longer run, to eliminate such arms.”

A dispute would inevitably lead to the mass destruction of both.

The conference’s first 15 years coincided with the Cold War’s greatest tensions: the Berlin Crisis, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Hungarian Revolution, the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia and the Vietnam War.Pugwash, as the conferences became known, “afforded a rare channel of communication between scientists from East and West,” MIT’s Journal of Cold War Studies reported in 2018. “In subsequent years, it came to provide a forum for second-track nuclear diplomacy.”

Indeed, the Nobel committee noted that the Pugwash movement helped open communication backchannels during an era that alternated between silence and periods of high tension marked by threats and hyperbole between East and West.It provided background work to the Partial Test Ban Treaty (1963), the Non-Proliferation Treaty (1968), the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (1972), the Biological Weapons Convention (1972) and the Chemical Weapons Convention (1993).

In a 1999 interview with the University of California (Berkeley), McNamara credited a backchannel Pugwash initiative, codenamed PENNSYLVANIA, with laying the groundwork for talks that ended the Vietnam War. The Soviet Union’s last leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, acknowledged in a 2004 interview with The Journal of the Federation of American Scientists that the Pugwash organization influenced his decision-making. There have been 61 conferences and the primary goals of Pugwash remain the elimination of nuclear weapons and weapons of mass destruction.

“It is good to know that the [conference] is an ongoing, vibrant project that continues to bring together concerned scientists who fully understand the responsibility to humankind,” Gorbachev said in a statement prior to the 50-year anniversary conference.

He called for “an intellectual foundation for agreements that would dramatically cut the arsenals of nuclear weapons on their way to their elimination and prevent an arms race in space. We need your brainpower, not just to analyze the problem, but to find solutions.”

Concrete efforts to control the spread and influence of nuclear weapons essentially began with the 1959 Antarctic Treaty, banning militarization of the planet’s coldest continent. In 1963, the Americans and Soviets negotiated the Hot Line Agreement to reduce the risk of a nuclear exchange due to accident, miscalculation or surprise attack. A dedicated transatlantic cable and radiotelegraph circuits assured direct communications between the two sides. The system was updated in 1971 with two satellite communications circuits. Secure computer links and encrypted e-mail systems are used now.

Also in 1963, the Soviet Union, United Kingdom and U.S. negotiated the Partial Test Ban Treaty, prohibiting tests of nuclear devices in the atmosphere, in outer space and underwater. It allowed nuclear testing to continue underground, so long as radioactive debris is confined to the territorial limits of the testing state. The treaty has since been signed, acceded or succeeded by 135 countries. Two major nuclear powers, France and China, have not signed but they have abided by its provisions.

Treaties have since prohibited the deployment of nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction in orbit, on the moon, on the seabed, in Africa, Southeast and Central Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean and the South Pacific. The 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty limits the spread of military nuclear technology by the recognized nuclear-weapon states (U.S., U.S.S.R., U.K., France and China) to non-nuclear-weapon states seeking to develop or acquire such weapons.

Non-nuclear-weapon states agreed not to acquire nuclear arms and countries with nuclear weapons would negotiate for disarmament. The UN International Atomic Energy Agency oversees nuclear facilities in non-weapons states. The treaty has been signed, acceded or succeeded by 190 states and was extended indefinitely in May 1995. India, Pakistan, Israel, South Sudan and North Korea are not party to the treaty.

By the 1990s, the two main rivals in the nuclear arms race were negotiating reductions, beginning with the 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or START. It set a ceiling of 1,600 strategic nuclear delivery vehicles and 6,000 “accountable” warheads for each country. It cut U.S. long-range nuclear warheads by 15 per cent and the Soviets’ by 25 per cent.

Shortly after the treaty was signed, however, the Soviet Union dissolved. The former republics that possessed nuclear weapons—Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine—endorsed the treaty by signing the START I Protocol. It took effect in 1994 and, by 2002, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine no longer had nuclear arms.

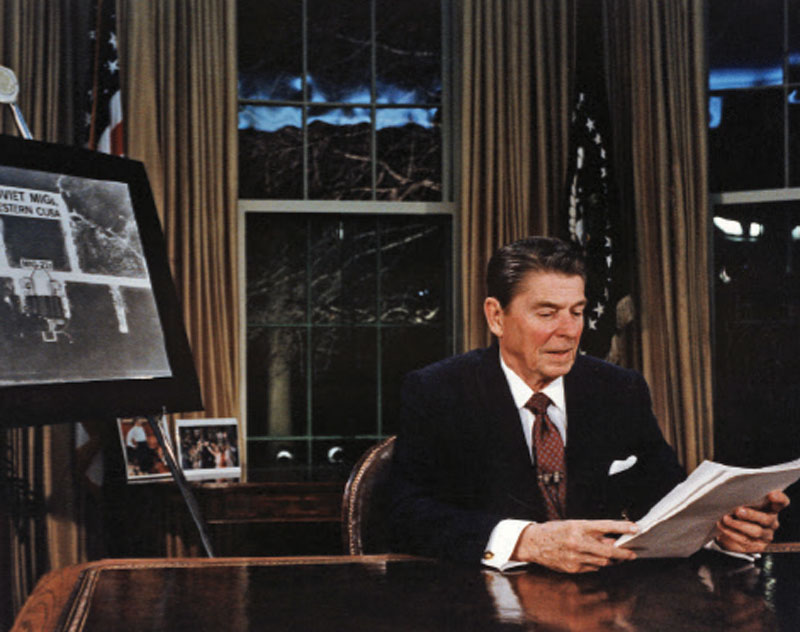

Reagan characterized MAD as “a suicide pact.”

START II, signed 1993, prohibited intercontinental ballistic missiles with multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles. It was scrapped after Russia withdrew in 2002. The two countries signed the New START Treaty in 2010, each pledging to reduce their strategic nuclear missiles by half. The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, or the Nuclear Weapons Ban Treaty, negotiated in 2017, was the first legally binding international agreement to prohibit nuclear weapons with the ultimate goal being their total elimination. It entered into force on Jan. 22, 2021.

A total of 197 states may become parties to the treaty, including all 193 UN-member states. As of July 2021, 56 states had ratified or acceded to the treaty. Signatories are prohibited from developing, testing, producing, stockpiling, stationing, transferring, using or threatening to use nuclear weapons. For nuclear-armed states joining the treaty, it provides a framework for negotiations leading to the verified and irreversible elimination of their nuclear weapons programs.

Despite all the treaties, Jervis wrote that, privately, most generals and top civilian leaders were “never convinced of the utility of MAD, and that skepticism was reflected in both Soviet and U.S. war planning.

“Each side strove for advantage, sought to minimize damage to its society, deployed defenses when deemed practical, and sought limited nuclear options that were militarily effective,” he said.

“Yet, for all these efforts, it is highly probable that a conventional war in Europe or, even more likely, the limited use of nuclear weapons would have prompted a full-scale nuclear war that would have resulted in mutual destruction.”

Toward the end of the Cold War, the Soviet military buildup convinced U.S. policymakers that the U.S.S.R. did not believe in MAD and was seeking nuclear advantage. Jervis said the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and its escalating involvements in Africa revealed that MAD could not protect all U.S. interests.

Talk drifted into the topics of nuclear superiority and the possibility of surviving nuclear war. Ultimately, President Ronald Reagan called for a resolution to the issue—and not by negotiation.“To look down to an endless future with both of us sitting here with these horrible missiles aimed at each other and the only thing preventing a holocaust is just so long as no one pulls the trigger—this is unthinkable,” Reagan declared. He characterized MAD as “a suicide pact,” and in March 1983 created something of an international crisis by announcing America’s intention to develop the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), or “Star Wars” program.

The project to develop a revolutionary, potentially space-based system to protect the United States from attack by intercontinental and submarine-launched ballistic missiles represented a game-changing technology that would threaten the balance of power, potentially tipping it decisively in America’s favour and, as a result, rekindling a Cold War-style arms race that was likely to end who-knows-where. As Jervis put it, “according to MAD, trying to protect yourself is destabilizing because it threatens the other side.”

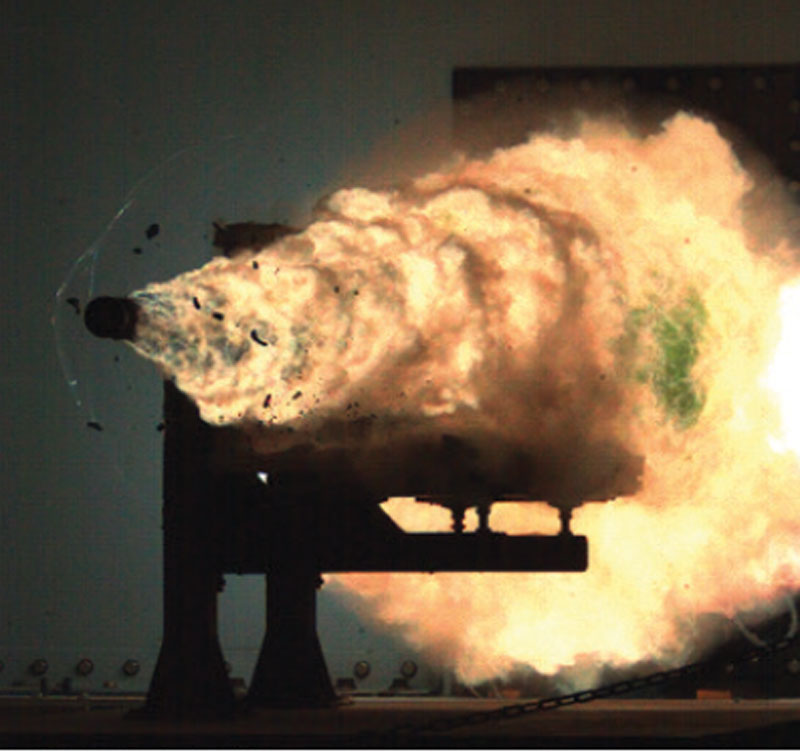

Preliminary research and testing went ahead on all manner of science fiction-sounding technologies such as X-ray lasers, neutral particle-beam accelerators, deuterium fluoride lasers and hypervelocity railgun technologies.But by 1987, the American Physical Society—made up mainly of physicists—concluded that the most promising technologies were still decades away from use and at least another decade of research was needed before it was determined whether such

systems were even possible.

The program’s budget was repeatedly cut after the report was published and political support for SDI ultimately collapsed. The program officially ended in 1993 when the Bill Clinton administration redirected efforts to theatre ballistic missiles. After the Soviet Union and East Bloc communism crumbled, concerns shifted to resurging terrorism and preventing the spread of nuclear weapons among non-state actors working outside the confines of international law and government—most recently among groups like al-Qaida and the Islamic State (ISIS).

In 2005, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the International Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism, which upgraded the global legal framework to counter terrorist threats. Based on a proposal made by the Russian Federation in 1998, it defines acts of nuclear terrorism and covers a broad range of potential targets, including nuclear power plants and reactors. It encourages co-operation and information-sharing between countries, including provisions for joint investigations and extraditions.

governmental organizations, the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction, known informally as the Mine Ban Treaty or simply the Ottawa Treaty, targeted anti-personnel landmines worldwide. It was negotiated in 1997 and took effect in 1999.

To date, there are 165 state parties to the treaty; 32 UN states did not sign on, including China, Russia and the United States. The Americans unilaterally committed to abandoning so-called “persistent” landmines, claiming its declaration is more comprehensive than Ottawa’s. American landmines now self-destruct within two days—four hours, in most cases—or deactivate when their batteries run out, usually within two weeks.

Although 31 signatories to the Ottawa Treaty had cleared all known mines from their territories by the end of 2015, accounting for millions of devices, critics say progress in overall reduction of mine usage is lacking. The 2016 Landmine Monitor Report, which measures the impact of the Ottawa Treaty, revealed that the number of new casualties of anti-personnel mines and explosive remnants of war rose 75 per cent to at least 6,461 people killed or wounded in 2015, compared to 3,695 in 2014. It was the largest number of casualties reported by the monitor since 2006.

“Mines still present in 63 countries and territories continue to kill and maim,” said Anne Héry, head of advocacy at Handicap International. “Almost every hour, a new casualty of these weapons is reported somewhere in the world. More than three-quarters of these casualties are civilians, and a third are children. Although clear advances have been made in the fight against mines, our struggle is not over yet.”

The 2020 report by the monitoring group said new use of improvised landmines by non-state armed groups was exacting a continuing high toll in civilian casualties.The latest report noted that more than 80 per cent of the world is bound by the Ottawa Treaty, while most of the 32 countries remaining outside of it are acting in de facto compliance, 23 years after it was adopted.

“This is a humanitarian success story,” said Steve Goose, Human Rights Watch arms division director and a contributor to the 2020 report. Only one state that is not party to the treaty—Myanmar—was confirmed to have used anti-personnel landmines during the reporting period from mid-2019 through October 2020.During that time, non-state actors were found to have used anti-personnel mines in at least six countries: Afghanistan, Colombia, India, Libya, Myanmar and Pakistan.

“The vast destruction of anti-personnel mine stocks continues to be one of the great successes of the Mine Ban Treaty,” said a report summary. “To date, States Parties have destroyed more than 55 million stockpiled anti-personnel mines, including more than 269,000 destroyed in 2019.”Still, at least 5,554 casualties were recorded, more than half of them (2,949) caused by improvised mines. Civilians accounted for the vast majority (80 per cent) and children represented nearly half of those (43 per cent).

The 1998 Convention on Cluster Munitions, adopted in May 2008 in Dublin, has met with similar rates of success and failure.The treaty, which by July 2021 had been joined by 123 states, prohibits the use, transfer, production and stockpiling of cluster bombs. It also sets out a framework for victim assistance, clearance of contaminated sites, risk reduction education and stockpile destruction.

Cluster bombs can scatter more than 2,000 “submunitions”—known as bomblets—over wide areas. Up to 40 per cent don’t explode on impact, either because they are too light, the ground is too soft, or they have faulty mechanisms. Many remain active. Like anti-personnel landmines they can explode at any time.

The landmine and cluster munitions monitoring group reported on Sept. 15 that there were at least 360 new cluster munition-related casualties in 2020, caused either by attacks (142) or remnants (218). “This represents a continued increase from the updated annual totals in 2019 (317 casualties) and 2018 (277 casualties),” said the Cluster Munition Monitor 2021. “The real number of new casualties is likely to be much higher as many have gone unrecorded due to challenges with data collection.”

Civilians remained the primary victims of cluster munitions at the time of the attacks and after conflict had ended, accounting for all casualties recorded in 2020; 44 per cent of those whose ages are known were children. Incidents were recorded in Afghanistan, Cambodia, Iraq, Laos, South Sudan, Syria, Yemen and Nagorno-Karabakh. Twenty-six countries and three other areas are contaminated by unexploded bomblets.

“Unexploded submunitions remain an enduring threat,” said the monitor’s editor, Loren Persi. “Despite challenges, progress was reported in the work to clear and return land to communities, to provide focused risk education to those most under threat, and to deliver on the obligation of providing assistance to victims.”

The report cited stockpile destruction as a convention success story: 36 countries had destroyed 99 per cent of all declared cluster munitions stocks. In the last year alone, it said, Bulgaria, Peru and Slovakia destroyed 2,273 cluster munitions and more than 52,000 submunitions.The Czech Republic, the Netherlands and Slovakia destroyed their respective stocks of cluster munitions retained for research and training purposes, leaving only 10 countries with such permitted stockpiles.

Additionally, about 63 square kilometres of cluster munition-contaminated land was cleared and 81,000 submunitions were subsequently destroyed. Croatia and Montenegro brought to 12 the number of countries that have cleared their contaminated areas.Since 2013, 130 countries have signed or acceded to the UN-sponsored Arms Trade Treaty, regulating the international trade in conventional weapons.

“Almost every hour, a new casualty of these weapons is reported.”

Since the Second World War, the international community has negotiated some 40 arms control treaties and agreements, with varying degrees of success.Limiting humankind’s penchant for self-destruction is a constant process. More pacts are in the works, from attempts to limit the global trade in small arms (there are an estimated 100 million AK-47s alone in circulation) to decades-old talks aimed at banning weapons in space, an attempt to build on the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which forms the basis of international space law.

The roles of NGOs, scientists, independent thinkers and popular movements are fundamental to these processes and achievements.

Advertisement